Case 5

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

An electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination was requested.

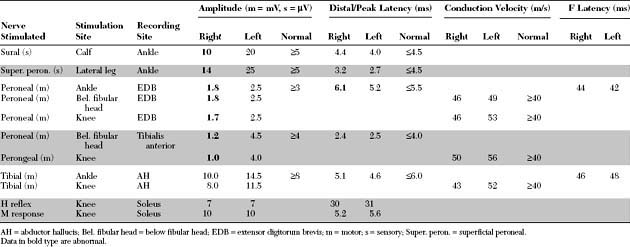

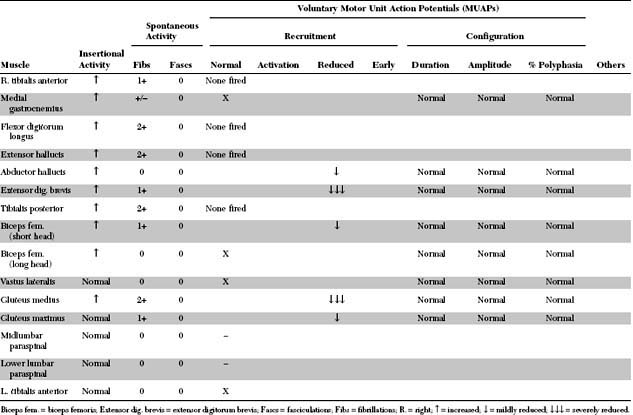

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

The relevant electrodiagnostic findings in this case are the followings:

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

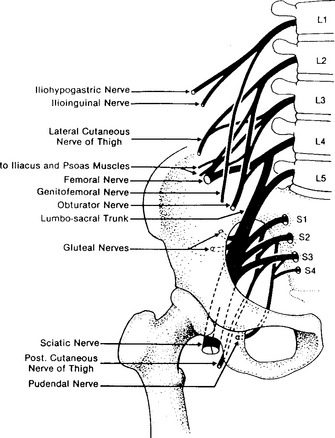

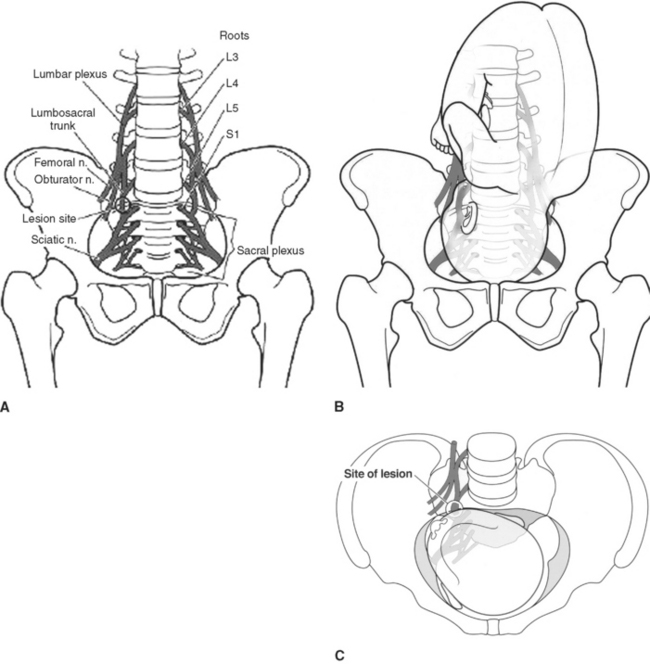

The lumbosacral plexus is divided anatomically into the lumbar plexus and the sacral plexus with a connecting nerve trunk, the lumbosacral trunk (Figure C5-1).

Clinical Features

Causes of lumbosacral plexopathy are shown in Table C5-2, but the following entities are the most common. Diabetic amyotophy is discussed in details in Case 7.

Intrapartum maternal lumbosacral plexopathy is a disorder caused by compression of the lumbosacral trunk by the descending fetal head during labor. The disorder is also known by a variety of names including postpartum footdrop, maternal birth palsy, maternal obstetric sciatic paralysis, traumatic neuritis of the puerperium, maternal obstetric paralysis, traumatic maternal birth palsy, obstetric neurapraxia, and obstetric lumbosacral plexus injury. The lumbosacral trunk is a long structure is most susceptible to pressure from the fetal presenting part at the pelvic rim, where it is unprotected by the psoas muscle (Figure C5-2). Incriminating risk factors for the development of intrapartum maternal lumbosacral plexopathy include short maternal stature, the birth of a large infant, or both. This leads to cephalopelvic disproportion and potential compression of the lumbosacral trunk by the fetal head against the pelvic rim. The labor is either prolonged or arrested and delivery is often accomplished by a caesarean section. The patient usually presents as a postpartum footdrop. However, sensory symptoms or pain referred to the symptomatic leg may be noted by some patients during active labor, because neural compression develops during fetal descent into the pelvis. However, these symptoms may be completely masked by epidural anesthesia for pain control, or dismissed by the treating physicians and nurses who may consider them part of labor pain. As delivery is completed by a cesarean section in many of these patients, using epidural or general anesthesia, foot drop was not detected until the immediate postpartum period. The clinical findings mimic a severe L-5 radiculopathy since the L-5 root fibers travel exclusively through the lumbosacral trunk. In contrast to L5 radiculopathy, however, these patients have always a foot drop since the tibialis anterior, the main ankle dorsiflexor, receives all its innervation (L5 and L4 fibers) via the lumbosacral trunk, while ankle dorsiflexion is often only modestly weak in selective L5 radiculopathy since the tibialis anterior has usually a dual L5 and L4 segmental innervation. Most patients recover in weeks to months, suggesting that the primary pathologic process is demyelination.

Idiopathic lumbosacral plexitis is the leg counterpart of neuralgic amyotrophy in the arm (acute brachial neuritis, Parsonage-Turner syndrome), although it is much less common. This disorder is somehow similar to diabetic amyotrophy, but it occurs in nondiabetics. Onset is acute or subacute and is heralded by severe leg pain followed by weakness that usually ensues several days to weeks after the onset of pain. Sensory symptoms are less prominent. The neurological findings may predominantly affect fibers of either the lumbar or sacral plexus. An elevated sedimentation rate may be present. The prognosis is good, but recovery of pain or weakness may be protracted, and recurrence is rare.

Electrodiagnosis

Differentiating a lumbosacral plexus lesion from lumbosacral radiculopathy is clinically difficult because the same fibers are affected at either location. Electrodiagnostically, this is accomplished mainly with needle EMG of the paraspinal muscles and the SNAPs:

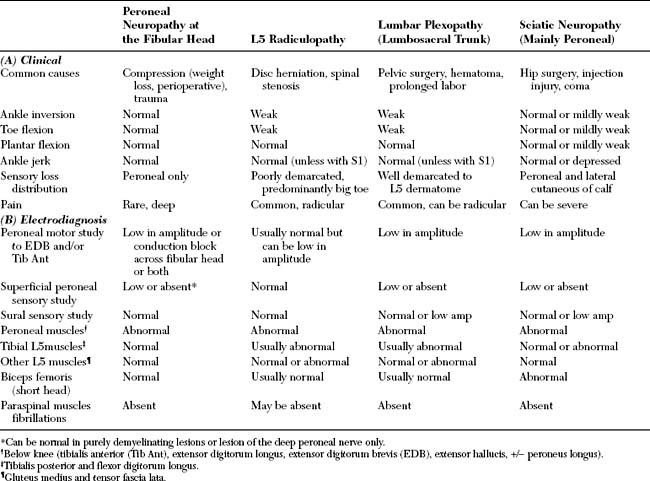

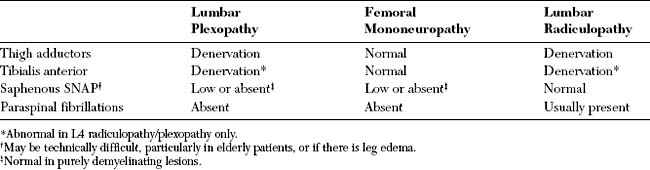

A lumbar plexus lesion may imitate an L4 radiculopathy or a femoral mononeuropathy (Table C5-3). The differential diagnosis may be difficult because the saphenous SNAP may be unelicitable in elderly, obese patients, or in patients with leg edema or associated peripheral polyneuropathy (as in diabetics). In contrast, the differential diagnosis of a lumbosacral trunk lesion includes an L5 radiculopathy or a peroneal mononeuropathy and is less difficult to confirm (Table C5-1). Finally, differentiating a sciatic mononeuropathy from a sacral plexopathy depends solely on the establishment of denervation in the gluteal muscles, and possibly in the external anal sphincter.

Asbury AK. Proximal diabetic neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:179-180.

Barohn RJ, et al. The Bruns-Garland syndrome (diabetic amyotrophy). Revisited 100 years later. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:1130-1135.

Feasby TE, Burton SR, Hahn AF. Obstetrical lumbosacral plexus injury. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:937-940.

Katirji B, Wilbourn AJ, Scarberry SL, et al. Intrapartum maternal lumbosacral plexopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:340-347.

Stewart JD. Focal peripheral neuropathies, 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press, 1993.

Subramony SH, Wilbourn AJ. Diabetic proximal neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 1982;53:293-304.

Whittaker WG. Injuries to the sacral plexus in obstetrics. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;79:622-636.

Young MR, Norris JW. Femoral neuropathy during anticoagulant therapy. Neurology. 1976;26:1173-1175.