Case 4

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

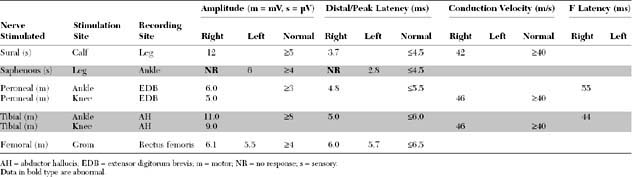

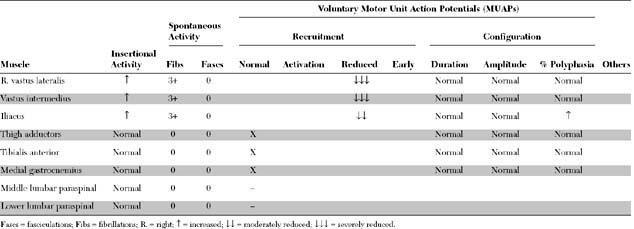

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

The pertinent electrodiagnostic (EDX) findings in this case include:

The prognosis for recovery is good because the distal femoral CMAP amplitude is normal, consistent with a predominant proximal demyelination. Note that the femoral nerve may be stimulated only at the inguinal canal distal to the location of the pelvic lesion. Some axonal loss obviously has occurred, based on the fibrillations and the absent saphenous SNAP, but these findings have no prognostic value for the outcome of motor function.

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

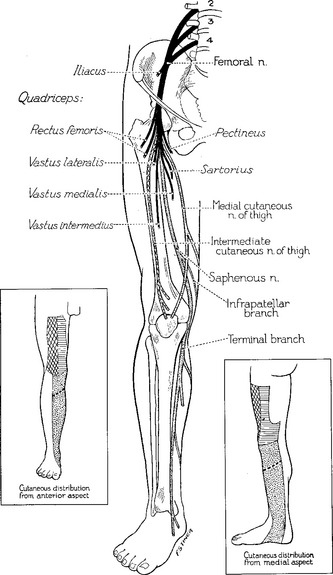

The femoral nerve emerges from the iliacus compartment after passing underneath the rigid inguinal ligament in the groin. About 4–5 cm before crossing the inguinal ligament, it innervates the iliacus muscle. Soon after passing under the inguinal ligament (lateral to the femoral vein and artery), the femoral nerve branches widely into (1) terminal motor branches to all four heads of the quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis) and sartorius muscles, and (2) three terminal sensory branches, the medial and intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh which innervate the skin of the anterior thigh, and the saphenous sensory nerve (Figure C4-1).

Clinical Features

The femoral nerve is a relatively short nerve. Its main trunk can be compressed at the inguinal ligament or in the retroperitoneal pelvic space. Most femoral mononeuropathies are iatrogenic, occurring during intra-abdominal, intrapelvic, inguinal, or hip surgical or diagnostic procedures. The nerve injury often results from direct nerve trauma or poor leg positioning during one of these procedures but may be due to a compressive hematoma or rarely due to inadvertent nerve laceration, suturing or stapling. Table C4-1 lists the various causes of femoral mononeuropathy grouped according to the site of injury.

|

1. Compression in the pelvis

– by retractor blade during pelvic surgery (iatrogenic): abdominal hysterectomy, radical prostatectomy, renal transplantation, etc.

|

Although the literature published in the 1950s and 1960s led many to believe that diabetes mellitus is associated with selective “diabetic femoral neuropathy,” it is now clear that this is a misnomer. Diabetic patients actually have more extensive peripheral nerve disease that involves the lumbar plexus and roots, and is better known as diabetic amyotrophy, diabetic proximal neuropathy, or diabetic radiculoplexopathy (see Case 7). Although the brunt of weakness in these patients often falls on the quadriceps muscle, mimicking selective femoral nerve injuries, careful clinical and needle EMG examinations reveal more widespread involvement of thigh adductors and sometimes foot dorsiflexors, muscles not innervated by the femoral nerve.

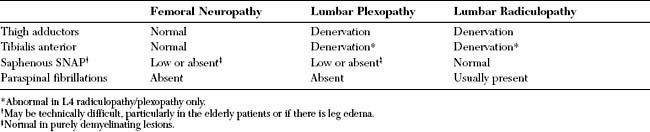

Femoral mononeuropathy should be differentiated from L2, L3, and L4 radiculopathy, and from lumbar plexopathy. Weakness of the thigh adductors, which are innervated by the obturator nerve, excludes a selective femoral lesion. Positive reversed straight leg test is common in lumbar radiculopathy, but it may occur with plexopathy and femoral nerve lesion caused by iliacus hematoma. In plexopathy or L4 radiculopathy, weakness of ankle dorsiflexion (tibialis anterior) is common.

Electrodiagnosis

The role of electrodiagnostic testing in femoral mononeuropathy is threefold.

The first role is to confirm the presence of a selective femoral nerve injury. This is particularly important when the neurologic examination is difficult to perform because of pain, recent pelvic surgery, or vaginal delivery. A femoral mononeuropathy may mimic a lumbar plexopathy and upper lumbar (L2, L3, or L4) radiculopathy (Table C4-2). The saphenous SNAP, which evaluates the postganglionic L4 sensory fibers, is often absent in femoral mononeuropathy and lumbar plexopathy but normal in L4 radiculopathy since the root lesion is intraspinal, i.e., proximal to the dorsal root ganglion. Rarely, the saphenous SNAP is normal in “purely” demyelinating femoral mononeuropathies where there is no wallerian degeneration which is usually complete in 10–11 days in sensory fibers. The saphenous SNAPs should be studied bilaterally for comparison, since these potentials may be difficult to obtain in the elderly and obese patients and in patients with leg edema. On needle EMG, fibrillation potentials and decreased recruitment of large and polyphasic MUAPs are seen in the quadriceps in all three entities (femoral mononeuropathy, lumbar plexopathy, or radiculopathy). However, these changes are also present in the thigh adductors (L2/L3/L4 obturator nerve) in patients with upper lumbar radiculopathy or plexopathy. Also, in L4 radiculopathy, similar changes may be present in the tibialis anterior (L4/L5 common peroneal nerve).

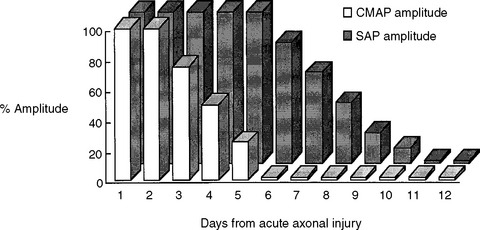

A third and important role of the EDX study is to prognosticate the recovery of motor function in acute femoral nerve lesions. A femoral CMAP amplitude and/or area is the most useful semiquantitative measure of the extent of femoral motor axonal loss. The femoral nerve could only be stimulated at the groin and, hence, lesions at the inguinal ligament or pelvis cannot be bracketed by two stimulation sites as done in many other peripheral nerve motor conduction studies. Femoral nerve stimulation at the groin is usually distal to the site of the lesion, and allows evaluation of a distal CMAP only. Care should be taken in accounting for the time for wallerian degeneration: the CMAP amplitude reaches its nadir in 4 to 5 days while the decrease in SNAP amplitudes lags behind and is completed in 8 to 11 days (Figure C4-2). Hence, the femoral CMAP must be obtained bilaterally for comparison at least after 4 to 5 days from injury before any conclusion could be made regarding the primary pathophysiologic process or prognosis. In contrast to the CMAP, fibrillation potentials are a poor quantitative measure of the extent of axonal loss since they are identified whenever axonal loss occurs, even if minimal. In other words, fibrillation potentials are extremely sensitive for the presence of any recent axonal loss, but do quantitate its degree, and are therefore, by themselves, poor indicators of the extent of peripheral nerve injury. Based on the above, the primary pathophysiologic process and prognosis of a unilateral femoral nerve lesion are assessed according to the following:

Al Hakim M, Katirji MB. Femoral mononeuropathy induced by the lithotomy position: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:891-895.

Calverley JR, Mulder DW. Femoral neuropathy. Neurology. 1960;10:963-967.

Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Wallerian degeneration in human nerves: serial electrophysiologic studies. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:687-693.

Jog MS, Turley JE, Berry H. Femoral neuropathy in renal transplantation. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21:38-42.

Katirji MB, Lanska DJ. Femoral mononeuropathy after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 1990;36:539-540.

Kent KC, Moscussi M, Gallagher SG, et al. Neuropathy after cardiac catheterization: incidence, clinical patterns and long term outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:1008-1012.

Kent KC, Moscucci M, Mansour KA, et al. Retroperitoneal hematoma after cardiac catheterization: prevalence, risk factors, and optimal management. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:905-910.

Kim DH, Kline DG. Surgical outcome for intra- and extrapelvic femoral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:783-790.

Kuntzer T, Van Melle G, Regli F. Clinical and prognostic features in unilateral femoral neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:205-211.

Kvist-Poulsen H, Borel J. Iatrogenic femoral neuropathy subsequent to abdominal hysterectomy: incidence and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:516-520.

Simmons CJr., Izant TH, Rothman RH, et al. Femoral neuropathy following total hip arthroplasty. Anatomic study, case reports, and literature review. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6:S57-66.

Vargo MM, Robinson LR, Nicholas JJ, et al. Postpartum femoral neuropathy: relic of an earlier era? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:591-596.

Weber ER, Daube JR, Coventry MB. Peripheral neuropathies associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1976;58A:66-69.

Young MR, Norris JW. Femoral neuropathy during anticoagulant therapy. Neurology. 1976;26:1173-1175.