Case 26

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

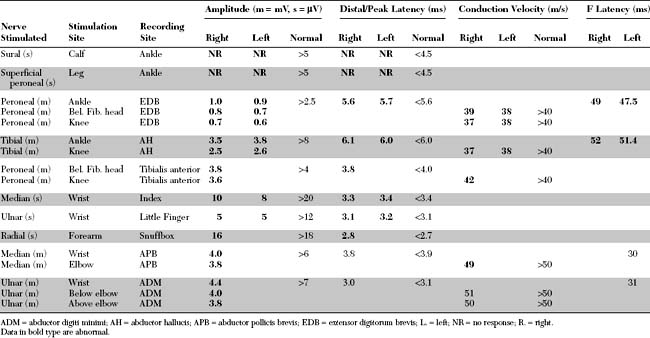

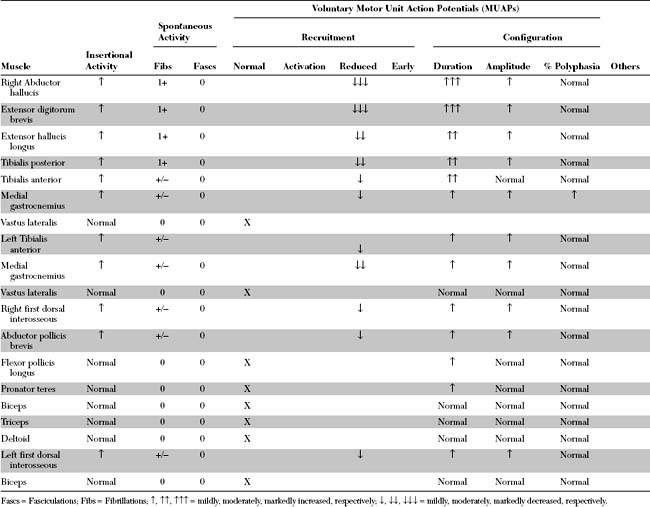

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

The abnormal EDX findings in this case include:

DISCUSSION

Definition and Pathogenesis

Peripheral Polyneuropathy

The myriad of etiologies of peripheral neuropathy pose a daunting task for the clinician. Investigating peripheral neuropathy has included several approaches. First, is the pattern recognition approach where a diagnosis of a polyneuropathy is based on highly specific associated findings such as the Mee line in arsenic or thallium poisoning, red tongue in vitamin B12 deficiency, or predilection of the sensory loss to cool areas of the body (such as earlobes, nipples, and buttock) in leprosy. Unfortunately, this approach applies to a minority of patients usually with advanced disease, requires a vast clinical experience and is mostly accomplished by senior neurologists. The second approach frequently used by many physicians (including some neurologists) is a “shotgun” approach by ordering a battery of tests on every patient with a neuropathy. This irrational approach is costly and may result in incorrect diagnosis secondary to incidental abnormalities, such as elevated blood glucose in a patient with CIDP. The third recommended approach is a systematic approach that utilizes mainly the clinical findings and EDX studies to generate a more limited differential diagnosis and help guide the laboratory investigations necessary for establishing a final diagnosis (Table C26-1). Additional studies that are useful in the accurate diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy include autonomic testing, quantitative sensory testing, antibody testing, and skin or cutaneous nerve biopsy.

Table C26-1 Essential Steps in the Classification and Etiologic Diagnosis of Peripheral Polyneuropathy

CIDP = chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; CMT = Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HNPP = hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy.

* Include diabetes mellitus, uremia, thyroid disorders.

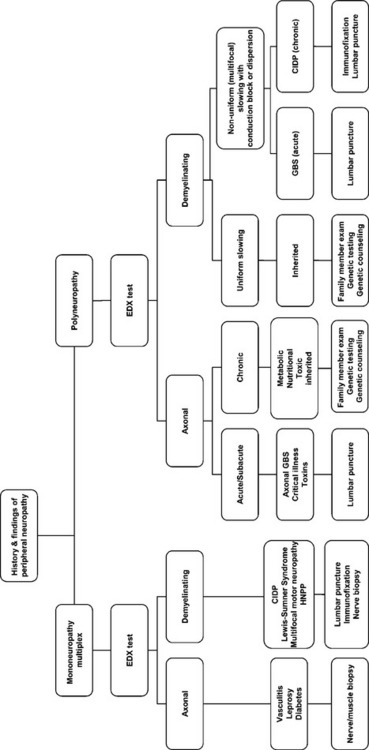

It is important to try defining the predominant pathophysiologic mechanism of the polyneuropathy, though the clinical examination is often unable to discriminate between a primarily axonal and demyelinating polyneuropathy. Demyelinating polyneuropathies have a limited number of etiologies, while the causes of axonal polyneuropathies, particularly those that are chronic and affect the sensory and motor axons, are numerous (Table C26-2).

Table C26-2 Common Causes of Chronic Symmetrical Axonal Peripheral Polyneuropathies

CMT = Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV1 = human T lymphotropic virus type 1; MGUS = monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus.

Alcoholic Polyneuropathy

The clinical manifestations of alcoholic polyneuropathy are typical of a length-dependent generalized, sensorimotor polyneuropathy. The neuropathy is often asymptomatic and only detected by clinical or EDX examination. The symptoms begin usually symmetrically with numbness, paresthesias, and burning feet, followed by cramps, weakness, and sensory ataxia. The symptoms are chronic and usually evolve slowly over months or years. Overt manifestations of autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic hypotension, are relatively uncommon. Weight loss, often in the range of 30–40 pounds or about 10% of body weight, is common but not always present. The neurological examination discloses a sensory loss to most modalities and muscle weakness in the lower extremities in a distal to proximal gradient. Allodynia and calf tenderness may also be present. Areflexia or hyporeflexia is also worse distally. Findings of other neurological alcoholic-nutritional deficiency states may coexist, such as cerebellar degeneration or Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. The laboratory tests are most useful in excluding other causes of polyneuropathy. Macrocytic anemia, abnormal liver function tests, and MRI evidence of cerebellar atrophy are common supportive findings for alcoholism.

Electrodiagnosis

At the completion of the EDX study, the clinician should be able to better characterize the polyneuropathy and classify its pathophysiology. This helps establish a relatively short differential diagnosis and work-up aimed at identifying the cause of the neuropathy and planning its management (Figure C26-1).

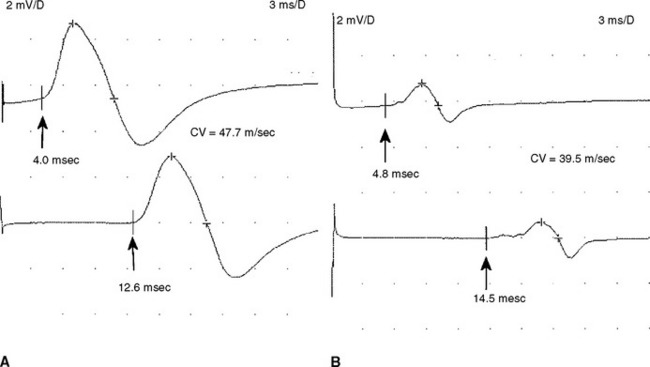

Analyzing conduction times (velocities and latencies), as well as CMAP amplitude, area, and duration, is an essential exercise in the EMG laboratory for establishing the primary pathologic process of a polyneuropathy. In most situations, the polyneuropathy falls in one of the two categories based on which of the two primary nerve fiber components is dysfunctional: the axon or its supporting myelin. Occasionally, such as in very mild polyneuropathies or in severe situations associated with absent sensory and motor responses, it may be difficult to establish the primary pathology based on EDX studies.

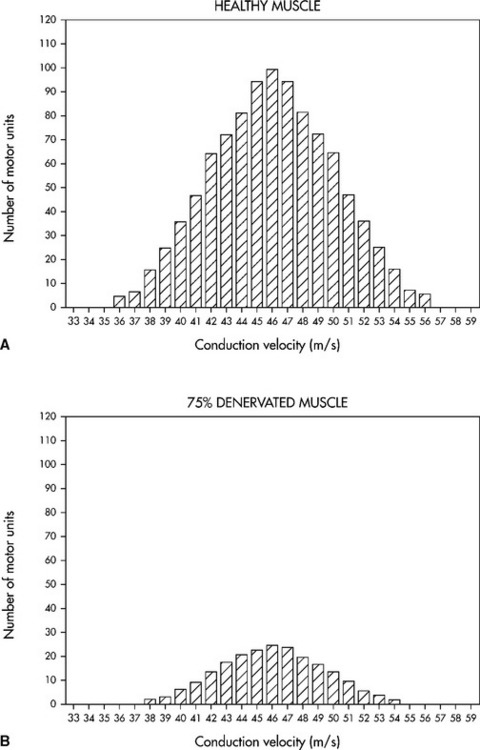

Needle electromyography in axonal polyneuropathy often discloses changes consistent with symmetrical motor axon loss, in a distal to proximal gradient, manifested by fibrillation potentials and reinnervation MUAPs of increased duration, amplitude, and polyphasia.

Asbury AK, Gilliatt RW. The clinical approach to neuropathy. In: Asbury AK, Gilliatt RW, editors. Peripheral nerve disorders. London: Butterworths; 1994:1-20.

Behse F, Buchthal F. Alcoholic neuropathy: clinical, electrophysiological and biopsy findings. Ann Neurol. 1977;2:95-110.

Claus D, Eggers R, Engelhardt A, et al. Ethanol and polyneuropathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1985;72:312-316.

England JD, Asbury AK. Peripheral neuropathy. Lancet. 2004;363:2151-2161.

Herrnmann DN, Logigian EL. Approach to peripheral nerve disorders. In: Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, Ruff RL, Shapiro EB, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002:501-512.

Hughes RAC. Peripheral neuropathy. BMJ. 2002;324:466-469.

McLeod JG. Alcohol, nutrition, and the nervous system. Alcoholic neuropathy. Med J Aust. 1982;2:274-275.

Shields RW. Alcoholic polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:183-187.

Shields RW. Nutritional AMD alcoholic neuropathies. In: Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, Ruff RL, Shapiro EB, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002:622-636.

Vrankcken AFJE, et al. Feasibility and cost efficiency of a diagnostic guideline for chronic polyneuropathy: A prospective implementation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:397-401.

Wein TH, Albers JW. Electrodiagnostic approach to the patient with suspected peripheral polyneuropathy. Neurol Clin N Am. 2002;20:503-526.