Case 23

QUESTIONS

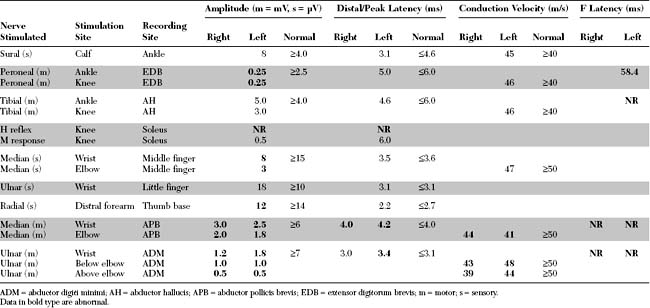

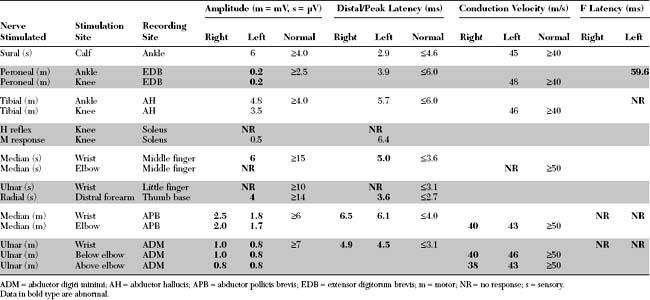

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

DISCUSSION

Rapidly Progressive Quadriparesis: Differential Diagnosis

Quadriparesis progressing over days to weeks is a relatively common neurological presentation. Usually, the history is one of an ascending paresis beginning in the lower limbs and progressing cephalad to trunk and upper limb muscles, and often weakening the respiratory, bulbar, and ocular muscles. Descending weakness, progressing in the opposite direction, may occur but is less common. Causes of nontraumatic rapidly progressive quadriparesis are best discussed using the neuraxis as an anatomical guideline. Since many of the disorders manifesting this presentation are due to lower motor neuron dysfunction, it is useful to use the different elements of the motor unit as a tool in setting a complete differential diagnosis (Table C23-1).

Adapted from Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC et al., eds. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

Certain clinical features and diagnostic studies are useful in establishing the correct diagnosis:

Clinical Features

Typically, GBS develops over the course of a few days. Limb weakness appears simultaneously with a slight tingling and impairment of sensation in the hands and feet. The sensory symptoms are rarely painful while myalgia and back pain are common. Weakness usually ascends from the lower limbs to the upper limbs and, sometimes, to the cranial nerves. Less commonly, the weakness in GBS is descending. Facial weakness occurs in approximately one half of patients, and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation occurs in one-third. Typically, progression lasts up to 4 weeks, while progression exceeding 4 weeks suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). Cerebrospinal fluid protein usually rises during the second week of illness, without pleocytosis (albuminocytologic dissociation). The presence of CSF pleocytosis is not incompatible with GBS, but if it is significant (>50 cells), other diagnoses, particularly infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), should be suspected. The frequency of various GBS manifestations is shown in Table C23-2.

Table C23-2 Frequency of Features and Clinical Variants of Acute Guillain-Barré Syndrome

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Condition | Initially | In Fully Developed Illness |

| Features of Syndrome | ||

| Paresthesias | 70 | 85 |

| Weakness | ||

| Arms | 20 | 90 |

| Legs | 60 | 95 |

| Face | 35 | 60 |

| Oropharynx | 25 | 50 |

| Ophthalmoparesis | 5 | 15 |

| Sphincter dysfunction | 15 | 5 |

| Ataxia | 10 | 15 |

| Areflexia | 75 | 90 |

| Pain | 25 | 30 |

| Sensory loss | 40 | 75 |

| Respiratory failure | 10 | 30 |

| CSF protein >0.55 g/L | 50 | 90 |

| Abnormal electrophysiologic findings | 95 | 99 |

| Clinical variants* | ||

| Fisher syndrome | 5 | |

| Weakness without paresthesias or sensory loss | 3 | |

| Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial weakness | 3 | |

| Paraparesis | 2 | |

| Facial paresis with paresthesias | 1 | |

| Pure ataxia | 1 | |

* Variants are associated with diminished reflexes, demyelinating features as detected on electrophysiologic studies, and elevated cerebrospinal concentrations of fluid protein. Frequencies shown are those found in fully developed illness.

From Ropper AH. The Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1130–1136, with permission.

Because of its similarity to its animal analogue, experimental allergic neuritis, GBS was considered to be a single disorder characterized by an acute immune attack on myelin, hence the term acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP). As the name implies, AIDP is characterized by prominent demyelination and inflammatory infiltrates in the spinal roots and nerves. Criteria for the diagnosis of GBS are based on the AIDP prototype and include both clinical and laboratory findings (Table C23-3). Until recently, AIDP had been used interchangeably with GBS. However, it is now well recognized that axonal forms of GBS exist. Several studies during the last two decades have documented that, although most cases of GBS are characterized by segmental demyelination, many patients with typical GBS have evidence of primary axonal degeneration (“axonal” GBS). GBS may be due to a pure motor axonopathy, named acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), or a mixed sensorimotor axonopathies, named acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) (Table C23-4). In addition to their electrophysiologic characteristics, the subtypes of GBS have characteristic pathological findings, with evidence of vesicular demyelination in AIDP and axonal phagocytosis in AMAN and AMSAN. Also, there is a strong association between GBS, particularly the AMAN form, with a preceding Campylobacter jejuni infection and the presence of serum antibodies directed toward ganglioside M1 (anti-GM1).

Table C23-3 Diagnostic Criteria for Guillain-Barré Syndrome (Mainly Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy)

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CSN = central nervous system; NCV = nerve conduction velocity; NCS = nerve conduction studies.

Modified from Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol 1990;27(Suppl): S21–S24.

Table C23-4 Classification of Guillain-Barré Syndrome

In addition to the three major subtypes of GBS, many variants of the typical GBS presentation exist. Among them, Miller-Fisher syndrome is the most widely known. It consists of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia. Others include a pure sensory form, an ataxic form, a pharyngeal–cervical–brachial regional form, and a pure autonomic form. Thus, GBS is a syndrome that encompasses many disorders with similar clinical presentations but likely with different etiologies and pathophysiologies (Tables C23-2 and C23-4).

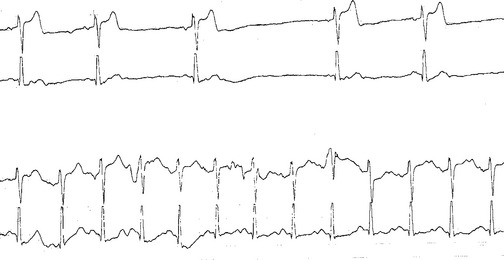

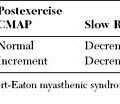

Most patients with GBS ultimately recover, but the prognosis is extremely variable. The plateau phase usually lasts several days or weeks but may persist for months in severe cases with quadriplegia and respiratory failure. The mortality rate has declined with the advent of critical care units and has ranged from 2 to 10%, mostly due to pulmonary embolism and cardiac arrhythmia (Figure C23-1). Approximately 20% of patients have permanent disability, and 10% of these are severely disabled. Advanced age, history of preceding diarrheal illness, recent CMV infection, rapid evolution of weakness, prolonged plateau before recovery, and ventilator dependency predicts a poor prognosis. Patients with AMSAN have the worst prognosis, while patients with AMAN surprisingly have a prognosis and recovery rate similar to patients with AIDP, despite electrophysiologic and pathologic evidence of axonal degeneration. This is best explained by a distal motor axonal loss (intramuscular motor nerve terminals) and rapid reinnervation. The best prognostic indicator of poor outcome is an average CMAP amplitude at plateau of less than 20% of the lower limit of normal. To rule out distal demyelination (i.e., distal conduction block) as a cause of low CMAP amplitudes, sequential EDX studies are often required.

Electrodiagnostic Features

Diagnostic Role of Electrodiagnostic Evaluation

The EDX study, and in particular its nerve conduction studies (NCS) component, is the most important ancillary method available to confirm the diagnosis of GBS. Yet, the electrodiagnosis of GBS continues to be a challenging task and is subject to errors that depend on the number of nerves studied and the experience of the electromyographer. The electrophysiologic evaluation of patients with GBS reveals a wide range of abnormalities caused by multifocal demyelination, axonal degeneration, or both. However, because of the patchy nature of demyelination in AIDP and its predilection to very proximal and very distal nerve segments (spinal roots and intramuscular branches, retrospectively), the EDX studies are not infrequently normal or reveal nonspecific neuropathic findings that are insufficient for a definite diagnosis, particularly when done during the first few days or weeks of disease onset. Also, the diagnosis of the axonal forms of GBS, AMAN and AMSAN, depends mostly on findings evidence of axonal loss without significant demyelination. In AMAN, which is associated with normal SNAPs, it is difficult to distinguish the disorder from a subacute axonal polyradiculopathies that also spare the SNAPs such as carcinomatous meningitis. In AMSAN, the presence of a mixed sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy may be impossible to distinguish, based on EDX studies only, from other causes of subacute axonal polyneuropathies such as critical illness polyneuropathy or polyneuropathies associated with porphyria, or drug or environmental toxins.

Motor Nerve Conduction Studies

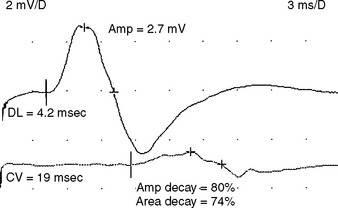

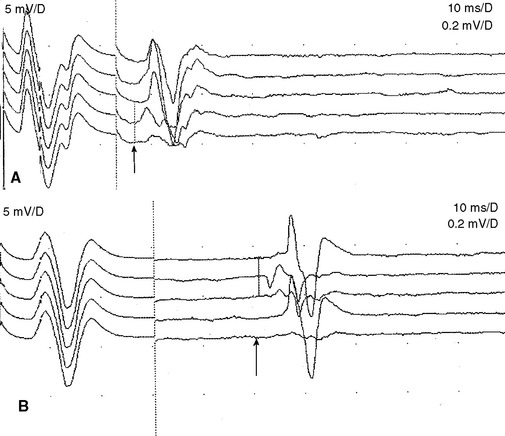

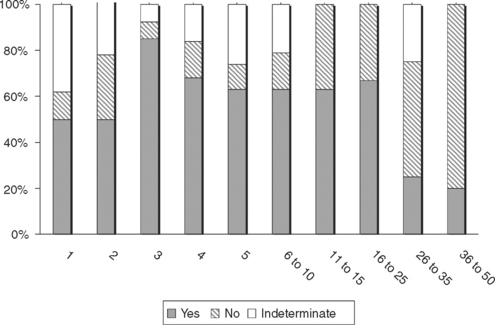

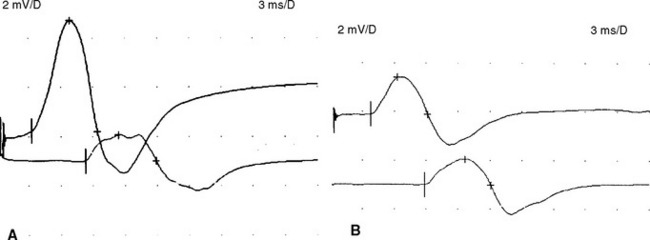

Electrophysiologic evidence of definite demyelination requires the presence of demyelination in at least two motor nerves with no evidence of coexisting entrapment syndromes. During the first two weeks of illness, slowing of conduction velocity in the demyelinating range (e.g., less than 70–80% of the lower limits of normal) is present in less than 25% of patients. Conduction block in one or more motor nerves, a strong evidence for acquired demyelination, is present in less than 30% of patients (Figure C23-2).

Sensory Nerve Conduction Studies

Limitations of the sural sparing pattern include that a pre-existing carpal tunnel syndrome may result in abnormally low amplitude or absent median and normal sural SNAPs. Hence, the sural sparing pattern should depend on at least two abnormally low-amplitude or absent hand SNAPs and normal sural SNAPs. Another limitation is that the sural SNAP is either low in amplitude or absent in elderly or obese patients, and in those with polyneuropathy. Technical considerations in hospitalized patients, especially those with quadriparesis or on mechanical ventilation in the intensive care units, also render studying sural SNAP difficult. In these cases, it is useful to assess the radial SNAP, since the median and ulnar SNAPs are more preferentially affected that the radial and sural SNAP. We found that a high sensory ratio (sural + radial SNAPs/median + ulnar SNAPs >1) is also strong evidence that support the diagnosis of AIDP. For example, we found that AIDP is 12 times more likely to have a sensory ratio of greater than 1 compared to diabetic neuropathy.

Late Responses

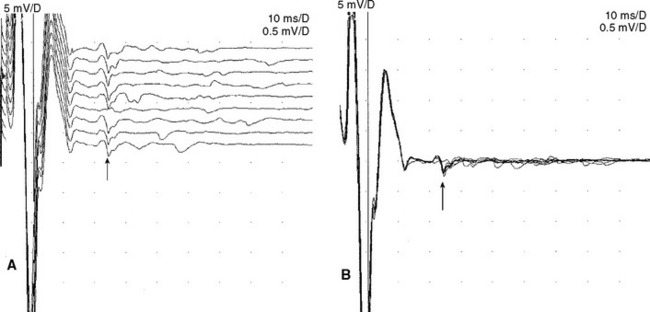

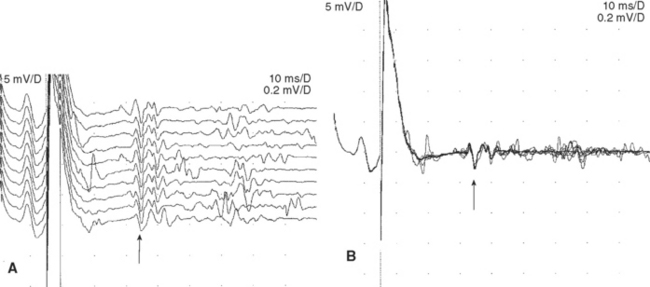

An absent tibial H reflex is the most common finding in patients with AIDP, being detected in about 95–100%. However, an absent H reflex is equivalent to an absent ankle jerk and is not specific (35% specificity) for AIDP as it is absent in most polyneuropathies as well as S1 radiculopathies and elderly subjects. Absent or impersistent F waves or delayed minimal F wave latencies are present in 40–80% of patients with AIDP but are, similar to the H reflex, nonspecific (33% specificity), since they accompany most peripheral polyneuropathies as well as radiculopathies and mononeuropathies. Absent or delayed minimal F wave latencies are most valuable when accompanied by normal or relatively preserved motor nerve conduction studies, a finding that is considered evidence of proximal demyelination (Figure C23-3). Another useful abnormality is the identification of A (axon) waves. Though A waves may be seen in up to 5% of asymptomatic individuals, particularly while studying the tibial nerve, recording multiple or complex A waves from several nerves is commonly associated with demyelinating polyneuropathies such as AIDP (Figures C23-4 and C23-5). The exact pathway of the A wave is unknown but it may be generated as a result of ephaptic transmission between two axons with the action potential conducting back down the nerve fiber to the muscle.

Diagnostic Criteria

Since AIDP is the most common type of GBS, the EDX criteria of GBS depend mostly on identifying segmental demyelination of peripheral nerves. The presence of conduction block, significant temporal dispersion, marked slowing of motor distal latencies, conduction velocities or F wave latencies are necessary findings for definite segmental demyelination. When the findings are multifocal or associated with conduction blocks or both, they are strong evidence for an acquired demyelinating neuropathy such as AIDP. Several NCS patterns emerge in patients with GBS ranging from normal studies to studies that are diagnostic of AIDP (Table C23-5).

Table C23-5 Common Nerve Conduction Patterns in Guillain-Barré Syndrome

CMAP = compound muscle action potential; SNAP = sensory nerve action potential.

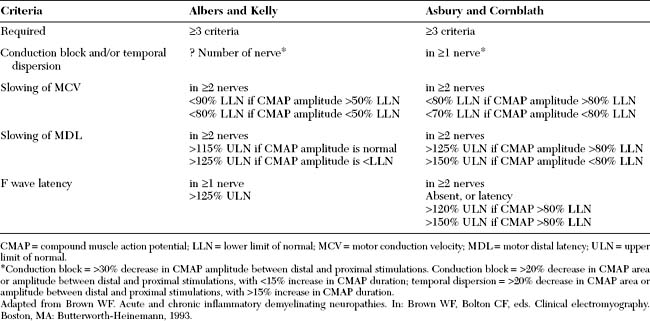

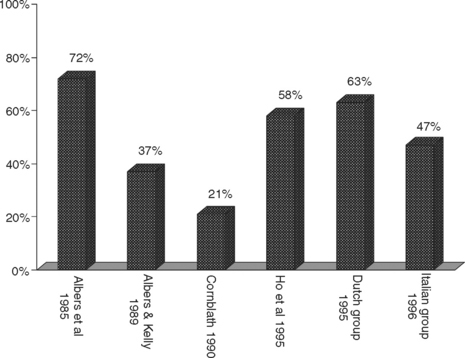

Several criteria have been proposed and none are universally accepted, some with strict definitions for demyelination and others with less rigid demands (Table C23-6). There are several limitations to the various EDX criteria for GBS. First, the exact cutoff of conduction velocities and distal latencies for establishing the diagnosis of primary demyelination and excluding axon loss disorders continues to be controversial. This is particularly true when the distal CMAPs are diminished below the lower limit of normal (LLN). It is clear that using the LLN for velocities or upper limit of normal for distal latencies as cutoffs is incorrect since many axonal neuropathies result in some degree of slowing. The available criteria were mostly based on consensus among groups of physicians. Earlier criteria assessed only velocities with no regards to CMAP amplitudes. More recently, Alberts and Kelly have used conduction velocity slowing of less than 90% of the LLN when CMAP amplitude is above 50% of LLN and less than 80% of the LLN when CMAP amplitude is below 50% of LLN. Asbury and Cornblath suggested conduction velocity slowing of less than 80% of LLN if the CMAP amplitude is greater than 80% of LLN and less than 70% of LLN if CMAP amplitude is greater than 80% LLN. There are no available criteria for the cutoff slowing when CMAP amplitude is very low, such as less than 20% of LLN, in order to distinguish severe axonal loss from segmental demyelination. Because of the differences of these EDX criteria, there is a considerable varaiation in the number of patients who would fulfill the criteria for AIDP (Figure C23-6). This has also resulted in disagreements between physicians and, sometimes, unfortunate misdiagnoses. The second limitation to these criteria is that the available criteria considers only the motor nerve conduction studies despite good evidence that sensory studies are important in the diagnosis of GBS and their use should be emphasized. These include the sural sparing pattern and an increased sensory ratio (sural + radial SNAPs/median + ulnar SNAPs) of more than 1.

Table C23-6 Two Commonly Used Electrodiagnostic Criteria for Definite Acquired Demyelinating Polyneuropathy Including AIDP

| Criteria | Albers and Kelly | Asbury and Cornblath |

|---|---|---|

| Required | ≥3 criteria | ≥3 criteria |

| Conduction block and/or temporal dispersion | ? Number of nerve* | in ≥1 nerve* |

| Slowing of MCV | in ≥2 nerves | in ≥2 nerves |

| <90% LLN if CMAP amplitude >50% LLN | <80% LLN if CMAP amplitude >80% LLN | |

| <80% LLN if CMAP amplitude <50% LLN | <70% LLN if CMAP amplitude <80% LLN | |

| Slowing of MDL | in ≥2 nerves | in ≥2 nerves |

| >115% ULN if CMAP amplitude is normal | >125% ULN if CMAP amplitude >80% LLN | |

| >125% ULN if CMAP amplitude is <LLN | >150% ULN if CMAP amplitude <80% LLN | |

| F wave latency | in ≥1 nerve | in ≥2 nerves |

| >125% ULN | Absent, or latency | |

| >120% ULN if CMAP >80% LLN | ||

| >150% ULN if CMAP >80% LLN |

CMAP = compound muscle action potential; LLN = lower limit of normal; MCV = motor conduction velocity; MDL = motor distal latency; ULN = upper limit of normal.

* Conduction block = >30% decrease in CMAP amplitude between distal and proximal stimulations. Conduction block = >20% decrease in CMAP area or amplitude between distal and proximal stimulations, with <15% increase in CMAP duration; temporal dispersion = >20% decrease in CMAP area or amplitude between distal and proximal stimulations, with >15% increase in CMAP duration.

Adapted from Brown WF. Acute and chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathies. In: Brown WF, Bolton CF, eds. Clinical electromyography. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

Figure C23-6 The percentage of patients with GBS fulfilling six various EDX criteria for AIDP (see Suggested Readings list) from a total of 43 patients with GBS in the first 4 weeks of illness.

(Adapted from Alam TA, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Electrophysiological studies in the Guillain-Barré syndrome: distinguishing subtypes by published criteria. Muscle Nerve 1998;21:1275–1279.)

It is clear that criteria with graded probability and various level of certainty for AIDP are needed, since the disorder has a wide range of EDX manifestations that may also change with time due to ongoing disease or due to the effect of remyelination or wallerian degeneration. Our recently published graded criteria utilized, in addition to one criteria of definite demyelination by Asbury and Cornblath, other nerve conduction abnormalities including absent/slowed F waves and sural sparing pattern. These criteria confirmed the diagnosis of AIDP in the first 2 weeks of illness with high specificity and a positive predictive value of 95–100% and with moderate sensitivity in about 65% of patients (Table C23-7).

Sequential studies, particularly in the first several weeks of illness, are valuable tools in GBS. The pathological process in GBS is dynamic during the early few weeks that a single EDX sampling may not be sufficient to establish the diagnosis. Unfortunately, many patients are now discharged to rehabilitative facilities before the third week of illness, and sequential studies are often not requested because clinical decisions have already been made and treatment has begun. However, there are several advantages of sequential studies:

Prognostic Role of Electrodiagnostic Evaluation

FOLLOW-UP

The patient lingered at a plateau for approximately 1 week before showing early signs of recovery. With rehabilitation, she improved gradually, first in the distal hand and foot muscles, then in the upper limbs, and finally in the lower limbs. She was able to feed herself 6 weeks after the onset of illness, sat independently at 2 months, and ambulated with a walker at 3 months. Four months after onset, the patient was ambulating independently but demonstrated mild residual hip flexor weakness (MRC 4+/5). She still was diffusely areflexic.

Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(Suppl):S21-S24.

Feasby TE, et al. An acute axonal form of Guillain-Barré polyneuropathy. Brain. 1986;109:1115-1126.

Griffin JW, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome in Northern China. The spectrum of neuropathological changes in clinically defined cases. Brain. 1995;118:577-595.

Griffin JW, et al. Pathology of the motor-sensory axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:17-28.

Ho MJ, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome in Northern China. Relationship to Campylobacter jejuni infection and anti-glycolipid antibodies. Brain. 1995;118:597-605.

Ho TW, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome in Northern China. The spectrum of neuropathological changes in clinically defined cases. Brain. 1995;118:577-595.

Hughes RA, Cornblath DR. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:1653-1966.

Illa I, et al. Acute axonal Guillain-Barré syndrome with IgG antibodies against motor axons following parental ganglioside. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:218-222.

Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, et al, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

McKhann GM, et al. Plasmapheresis and Guillain-Barré syndrome: analysis of prognostic factors and the effect of plasmapheresis. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:347-353.

McKhann GM, et al. Acute motor axonal neuropathy: a frequent cause of acute flaccidity in China. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:333-342.

Oomes PG, et al. Anti GM1 IgG antibodies and Campylobacter bacteria in Guillain-Barré syndrome: evidence of molecular mimicry. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:170-175.

Ropper AH. The Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1130-1136.

Alam TA, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Electrophysiological studies in the Guillain-Barré syndrome: distinguishing subtypes by published criteria. Muscle Nerve. 1998;21:1275-1279.

Albers JW, Donofrio PD, McGonagle TK. Sequential diagnostic abnormalities in acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:528-539.

Albers JW, Kelly JJJr. Acquired inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: clinical and electrodiagnostic features. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:435-451.

Al-Shekhlee A, Hachwi R, Preston DC, Katirji B. New criteria for early electrodiagnosis of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:66-72.

Al-Shekhlee A, Robinson J, Katirji B. Sensory sparing patterns and sensory ratio in acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:246-250.

Asbury AK, Cornblath DR. Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(Suppl):S21-S24.

Bansal R, Kalita J, Misra UK. Pattern of sensory conduction in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;41:433-437.

Bromberg MB, Albers JW. Patterns of sensory nerve conduction abnormalities in demyelinating and axonal peripheral nerve disorders. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:262-266.

Cornblath DR. Electrophysiology in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(Suppl):S17-S20.

Cornblath DR, et al. Motor conduction studies in Guillain-Barré syndrome: description and prognostic value. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:354-359.

Cleland JC, et al. Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: contribution of a dispersed distal compound muscle action potential to electrodiagnosis. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:771-777.

Gordon PH, Wilbourn AJ. Early electrodiagnostic findings in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:913-917.

Italian Guillain-Barré Study Group. The prognosis and mainprognostic indicators of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Brain. 1996;119:2053-2061.

Meulstee J, van der Meche FG. Electrodiagnostic criteria for polyneuropathy and demyelination: application in 135 patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome. Dutch Guillain-Barré Study Group. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:482-486.

Miller RG, et al. Prognostic value of electrodiagnosis in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:769-774.

Ropper AH, Wijdicks EFM, Shahani BT. Electrodiagnostic changes in early Guillain-Barré. A prospective study in 113 patients. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:881-887.

Triggs WJ, et al. Motor nerve inexcitability in Guillain-Barré syndrome: the spectrum of distal conduction block and axonal degeneration. Brain. 1992;115:1291-1302.

Van Der Meche FGA, et al. Patterns of conduction failure in the Guillain-Barré syndrome. Brain. 1988;111:405-416.

Dutch Guillain-Barré Study Group. Treatment of Guillain-Barré syndrome with high-dose immune globulins combined with methylprednisolone: a pilot study. Ann Neurol. 1994;34:749-752.

French Cooperative Group on Plasma Exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Efficiency of plasma exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome: role of replacement fluids. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:753-761.

French Cooperative Group on Plasma Exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Plasma exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome: one-year follow-up. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:94-97.

French Cooperative Group on Plasma Exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Appropriate number of plasma exchanges in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:298-306.

Hughes RAC, et al. Controlled trial of prednisone in acute polyneuropathy. Lancet. 1978;2:750-753.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome Steroidal Trial Group. Double-blind study of intravenous methylprednisolone in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 1993;341:586-590.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome Study Group. Plasmapheresis and acute Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurology. 1985;35:1096-1104.

Plasma Exchange/Sandoglobulin Guillain-Barré Syndrome Trial Group. Randomized trial of plasma exchange, intravenous immunoglobulin, and combined treatments in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 1997;349:225-230.

Van Der Mech FGA, Schmitz PIM, the Dutch Guillain-Barré Study Group. A randomized trial comparing intravenous immune globulin and plasma exchange in Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1123-1129.