Case 17

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

An electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination was performed.

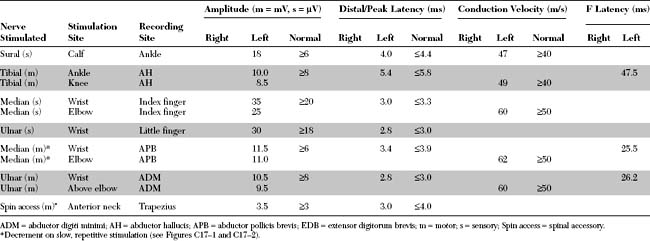

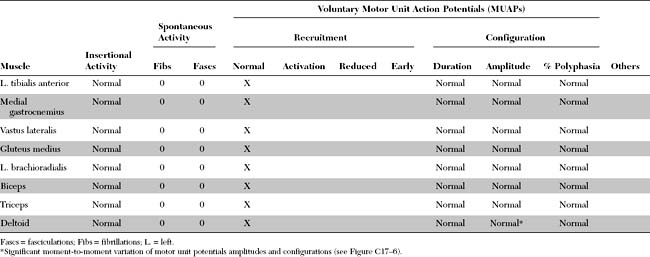

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Pertinent EDX findings include the following:

DISCUSSION

Anatomy and Physiology

Neuromuscular Junction

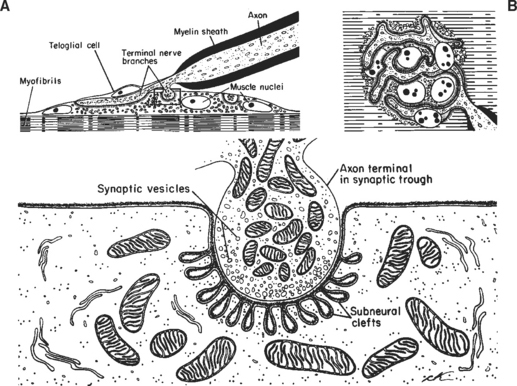

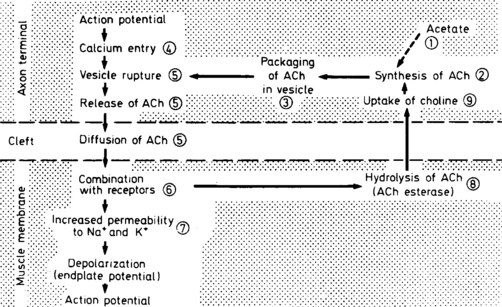

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the site where the motor neuron makes contact with the skeletal muscle fiber’s membrane (sarcolemma). It is near the center of the muscle fiber where there is a cup-shaped depression of the sarcolemma, called the endplate. The NMJ is a chemical synapse that is essential for transmitting action potentials from the terminal nerve branches to muscle fibers. This synapse utilizes acetylcholine (ACH) as a transmitter that binds to specific receptors in the junctional membrane, resulting local depolarizations that spread and trigger all-or-none muscle action potential. The NMJ is divided into a presynaptic terminal, a synaptic cleft, and a postsynaptic region (Figure C17-3).

Neuromuscular Transmission

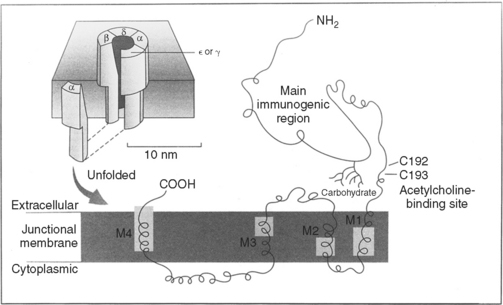

Clinical Features

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is the best understood and most thoroughly studied of all human organ-specific autoimmune diseases. It is characterized by a reduction of skeletal muscle postsynaptic ACH receptors resulting in a decrease in the EPP necessary for action potential generation. In the majority of patients, MG is caused by an antibody-mediated attack on the postsynaptic nicotinic ACH receptors in the neuromuscular junction. In a small number of patients, other antigenic targets, such as the muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK), may exist. Myoid cells and other stem cells within the thymus gland, which is hyperplastic in at least two-thirds of patients with MG, may serve as autoantigens by expressing on their surface the ACH receptor or one of its protein components.

The hallmarks of MG are muscle weakness and fatigability. The symptoms are intermittent and are usually worse with activity and improve after rest. Generally, patients are much better in the morning than in the evening. Ocular symptoms (diplopia and/or ptosis) are extremely common and are the presenting signs in more than one half of patients. Most importantly, almost all patients at some point during the course of their illness develop ocular manifestations. Also, the disorder continues to be restricted to the extraocular muscles in 15% of patients, hence the designation ocular myasthenia. Additionally, only 3–10% of patients with ocular myasthenia generalize if no other symptoms appear after three years from initial presentation. Bulbar muscle weakness is the initial presenting manifestation in about 20% of patients and is seen in over 30% of patients during the course of their disease. Bulbar weakness is a major contributor to disability throughout the course of the disease. It manifests as dysarthria, nasal speech, dysphagia, chewing difficulties, or nasal regurgitation. Occasionally, the jaw muscle weakness may be severe leading to a “jaw drop” and patients often hold their jaw closed, a highly pathognomonic manifestation of MG. Limb weakness, mostly of proximal muscles, is seen as the initial symptom in 20% of patients. At times, the generalized weakness is severe and involves the respiratory muscles, resulting in respiratory failure that requires mechanical ventilation, a situation often referred to as myasthenic crisis. Because of variable clinical severity, MG is usually classified into five main categories (Table C17-1).

Table C17-1 Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification

| Class I | Any ocular muscle weakness |

| May have weakness of eye closure | |

| All other muscle strength is normal | |

| Class II | Mild weakness affecting other than ocular muscles |

| May also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity | |

| IIa | Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles or both |

| May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles | |

| IIb | Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both |

| May also have lesser involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both | |

| Class III | Moderate weakness affecting other than ocular muscles |

| May also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity | |

| IIIa | Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles or both |

| May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles | |

| IIIb | Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both |

| May also have lesser involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both | |

| Class IV | Severe weakness affecting other than ocular muscles May also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity |

| IVa | Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles or both May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles |

| IVb | Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both |

| May also have lesser involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both | |

| Class V | Defined by intubation, with or without mechanical ventilation, except when employed during routine postoperative management. The use of a feeding tube without intubation places the patient in class IVb |

The diagnosis of MG may be made on clinical grounds, especially when reproducible fatigability of eyelids or extraocular muscles is confirmed. However, laboratory testing is frequently needed, and recommended, for confirmation (Table C17-2):

Table C17-2 Confirmatory Diagnostic Tests in Myasthenia Gravis

The differential diagnosis of generalized MG includes Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), botulism, congenital myasthenic syndromes, and chronic fatigue syndrome. LEMS presents with generalized weakness, areflexia, and autonomic symptoms, but it is not uncommon to confuse its EDX findings with those of MG (Table C17-3). Botulism is subacute and has usually prominent autonomic manifestations, including dilated pupils and ileus. Congenital myasthenic syndromes are extremely rare disorders and usually begin in childhood. The fatigue associated with chronic fatigue syndrome may mimic generalized MG, except for normal ocular and bulbar strength and normal serologic and EDX studies. Ocular myasthenia should be distinguished from Graves disease (thyroid orbitopathy), progressive external ophthalmoplegia, Kearns-Sayre syndrome, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, congenital myasthenic syndromes, and orbital apex or cavernous sinus mass compressing cranial nerves. In Graves disease, there is proptosis, conjunctival edema, and muscle enlargement (on imaging of the orbit); the forced duction test is positive. Progressive external ophthalmoplegia and Kearns-Sayre syndrome have usually symmetrical and slowly progressive ophthalmoplegia and ptosis. In Kearns-Sayre syndrome, there is associated multisystem involvement including pigmentary retinopathy, cerebellar ataxia, and cardiac conduction defects. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy is a late onset autosomal dominant disease with slowly progressive dysphagia and ophthalmoplegia. In compressive mass lesions, the extraocular weakness usually follows one or more oculomotor nerve distribution and the pupils are frequently involved. Imaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), might be required to rule out such a mass lesion within the orbit or cavernous sinus.

Table C17-3 Differential Diagnosis Between Generalized Myasthenia Gravis and Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

| Myasthenia Gravis | Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Ocular involvement | Common and prominent | Uncommon and subtle |

| Bulbar involvement | Common and prominent | Uncommon and subtle |

| Myotatic reflexes | Normal | Absent or depressed |

| Sensory symptoms | None | Paresthesias are common |

| Autonomic involvement | None | Dry mouth, impotence and gastroparesis |

| Tensilon test | Frequently positive | May be positive |

| Serum antibodies directed against | Postsynaptic Ach receptors or MuSK | Presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels |

| Baseline CMAPs | Normal | Low in amplitude |

| Postexercise CMAPs | No change | Significant facilitation |

| Slow repetitive stimulation | Decrement | Decrement |

| Rapid repetitive stimulation | No change or decrement | Increment |

| Single-fiber EMG | Increased jitter with blocking | Increased jitter with blocking |

| Rapid-rate stimulation jitter | Does not change or worsens jitter | Improves jitter |

CMAPs = compound muscle action potentials; EMG = electromyography, Ach = acetylcholine, MuSK = muscle-specific kinase.

Therapy for MG has improved dramatically over the past 30 years, and the current mortality from this disorder is near zero. Treatment consists of one or more of several modalities, often used separately or in combination (Table C17-4). Treatment choices are usually individualized to the patient depending on severity of illness, age, life style and career, associated complicating disorders, and the risk and benefit of various therapies.

Table C17-4 Therapeutic Modalities in Myasthenia Gravis

| Therapy | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., pyridostigmine) | Enhances neuromuscular transmission |

| Corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, etc. | Immunosuppression |

| Plasmapheresis | Removes antibodies from circulation |

| Intravenous immunoglobulins | Unknown (?downregulates antibody production) |

| Thymectomy | Unknown (?eliminates a source of antigenic stimulation [thymic myoid cells] and/or removes a reservoir of B lymphocytes) |

Electrodiagnosis

Nerve Conduction Studies

Sensory conduction studies are normal in MG. Similarly, routine motor conduction studies are usually normal. However, on rare occasions, the CMAP amplitudes are borderline or slightly decreased. This occurs in patients with prominent weakness, such as that associated with a myasthenic crisis, and is explained by prominent neuromuscular blockade beyond the safety factor (see repetitive nerve stimulation). In these situations, many muscle fibers do not reach threshold with a single stimulus, as is used with routine motor conduction studies, resulting in a small summated CMAP. It should be noted again that this is an extremely rare finding in MG. In fact, a presynaptic disorder, such as LEMS and botulism, should always be considered and excluded when the CMAP amplitudes are low or borderline. A presynaptic disorder is confirmed by looking for a significant (>50–100%) increment of CMAP amplitude after brief exercise and/or rapid, repetitive stimulation (see repetitive stimulation). Compound muscle action potential increment after brief exercise and/or rapid, repetitive nerve stimulation is not a feature of MG.

Needle EMG Examination

Needle EMG results usually are normal in MG. Three changes may, however, be seen. These include:

Repetitive Nerve Stimulation (RNS)

Basic Concepts

Electrophysiology

The rate at which motor nerves are stimulated dictates whether calcium plays a role in enhancing the release of ACH. Because Ca2+ diffuses out of the presynaptic terminal within 100 to 200 ms, a slow rate of stimulation (slower than every 200 ms) implies that the subsequent stimulus arrives long after calcium has dispersed. Thus, an interstimulus interval of greater than 200 ms, or a stimulation rate of less than 5 Hz, is considered a slow rate of repetitive stimulation. At this slow rate, the role of Ca2+ in ACH release is not enhanced. In contrast, with rapid repetitive stimulation (i.e., at an interstimulus interval of less than 200 ms, or a stimulation rate greater than 5–10 Hz), Ca2+ influx is enhanced greatly, which results in larger releases of ACH and a larger EPP.

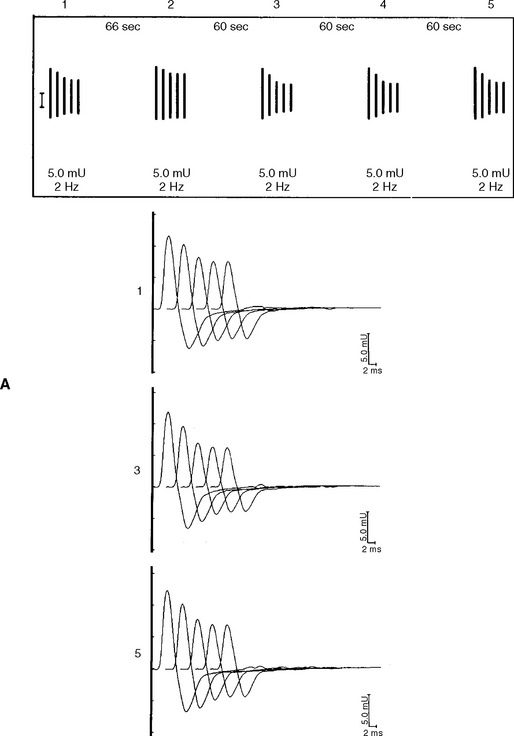

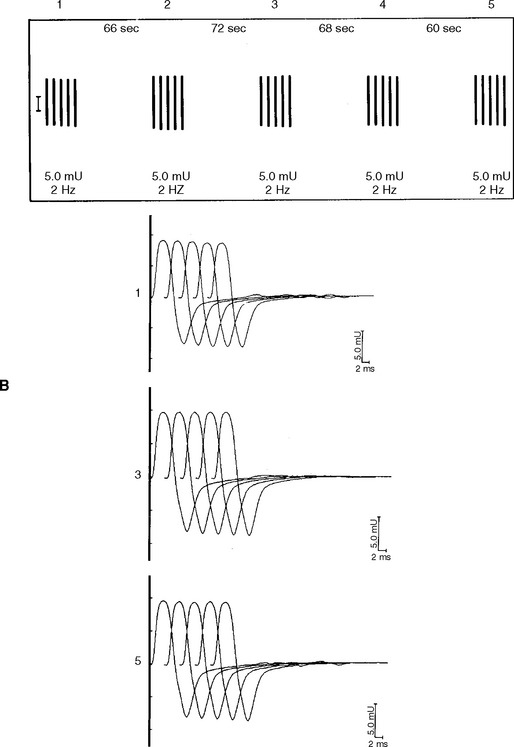

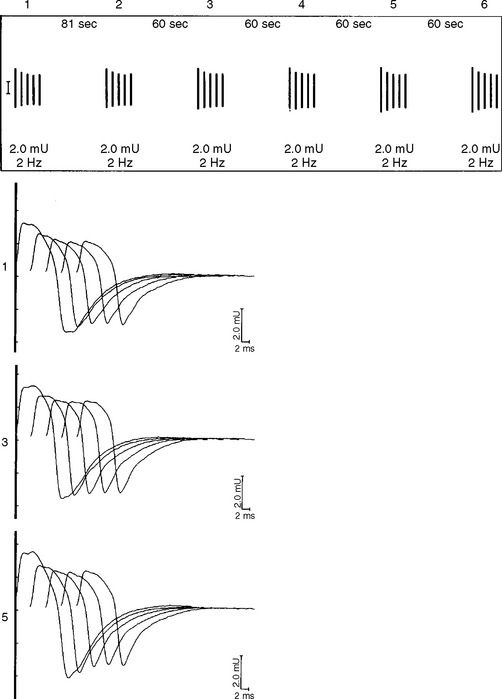

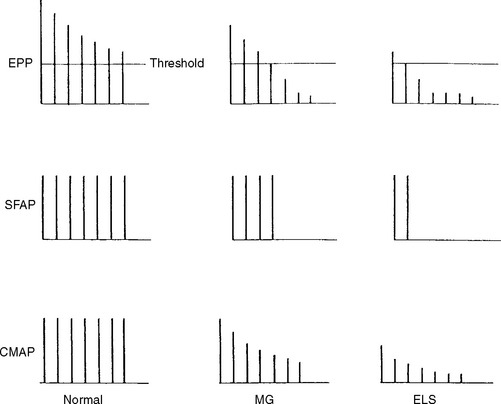

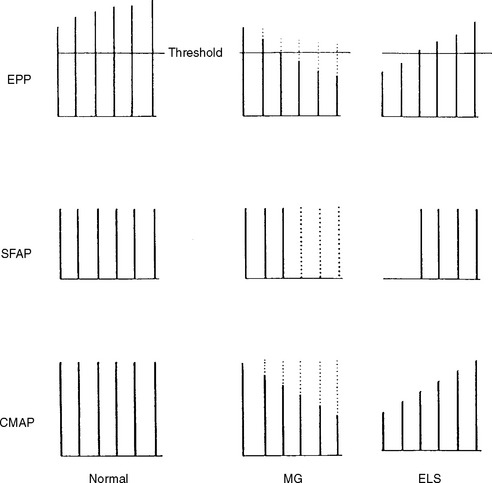

In normal conditions (Figures C17-7 and C17-8), both rates of stimulation generate MFAPs in all muscle fibers since the EPPs remain above threshold because of the safety factor. Thus, at both stimulation rates, all muscle fibers generate MFAPs, and the CMAP (summated MFAPs) does not change (i.e., no decrement or increment).

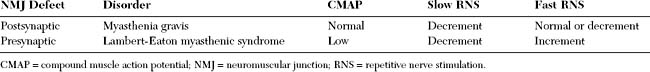

However, the postsynaptic disorders, such as MG, are characterized by the following (Tables C17-3 and C17-5):

Table C17-5 Compound Muscle Action Potential and Repetitive Abnormalities Characteristic of Common Neuromuscular Junction Disorders

In contrast, the presynaptic disorders, such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome, are characterized by the following (See Tables C17-3 and C17-5):

Technical Considerations

Measurements

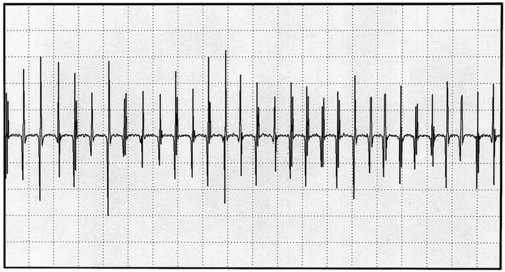

In MG, slow RNS results in a CMAP decrement. The greatest decrement in amplitude occurs between the first and second responses, while the maximal amplitude decrement is often between the first and or third fourth responses. By the fifth response, the decrement levels off (see Figures C17-1A and C17-2). For these reasons, a train of four or five stimuli at 2 Hz usually is satisfactory and is best tolerable. The decrement is calculated as follows:

Single-Fiber EMG

Technical Considerations

Voluntary Single-Fiber EMG

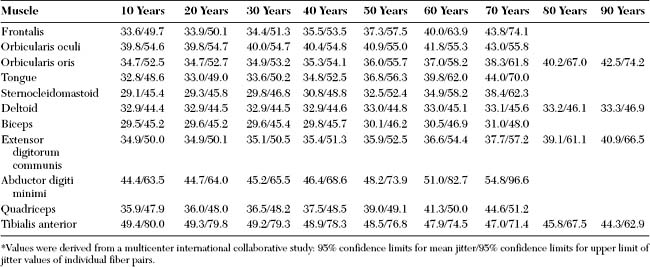

Voluntary (recruitment) SFEMG is the most commonly used method for activating motor units: the patient activates and maintains the firing rate of the motor unit. This technique is not possible if the patient cannot cooperate (e.g., child, dementia, coma, or severe weakness), and is difficult if the patient is unable to maintain a constant firing rate (e.g., tremor, dystonia, or spasticity). With minimal voluntary activation, the needle is positioned until at least two muscle potentials (a pair) from a single motor unit are recognized. When a muscle fiber pair is identified, one fiber triggers the oscilloscope (triggering potential), and the second precedes or follows the first (slave potential). Normal values for jitter (mean and individual values) are available from a multicenter international collaborative effort (Table C17-6). Jitter values differ between muscles, and tend to increase with age, particularly over the age of 50 years.

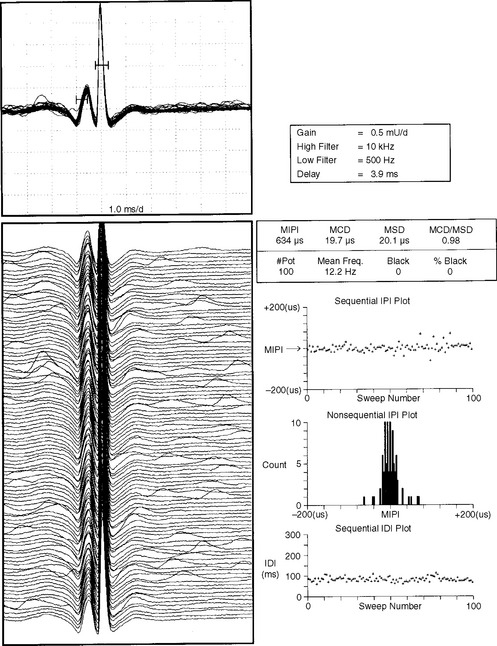

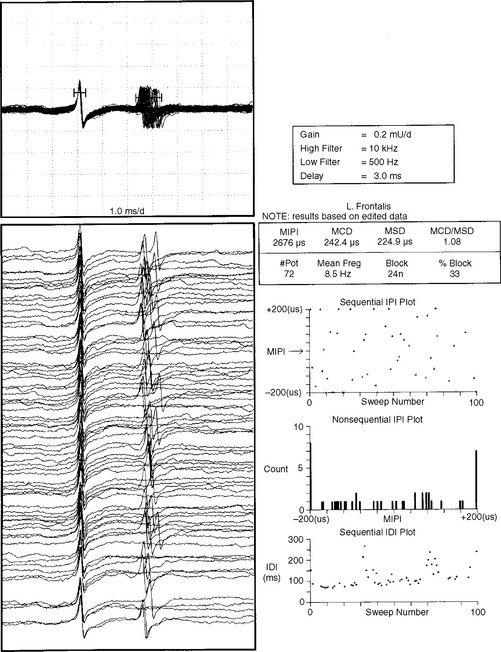

where MCD is mean consecutive difference, IPI is interpotential interval, and N is the number of discharges (intervals) recorded. In practice, an MCD should be calculated from at least 50 interpotential intervals. Analysis of 10 to 20 pairs frequently is needed for a mean MCD to be reported. Although the jitter can be measured using a mean and a standard deviation, it is measured more reliably by the MCD because of the potential change in the mean IPI over time. Jitter is best expressed as the mean MCD of approximately 10 to 20 muscle fiber pairs (Figure C17-9).

Neuromuscular blocking is defined as the failure of transmission of one of the potentials. Blocking represents the most extreme abnormality of the jitter. Blocking is calculated as the percentage of discharges of a motor unit in which a single-fiber potential does not fire. For example, during 100 discharges of the pair, if a single potential is missing 30 times, the blocking occurs at a rate of 30%. In general, blocking occurs when jitter values are significantly abnormal.

In patients with MG, abnormal jitter values are common and frequently are accompanied by blocking (Figure C17-10). This reflects the failure of one of the muscle fiber pairs to transmit an action potential because of the failure of the EPP to reach threshold. The results of SFEMG jitter study are expressed by: (1) the mean jitter of all potential pairs, (2) the percentage of pairs with blocking, and (3) the percentage of pairs with normal jitter.

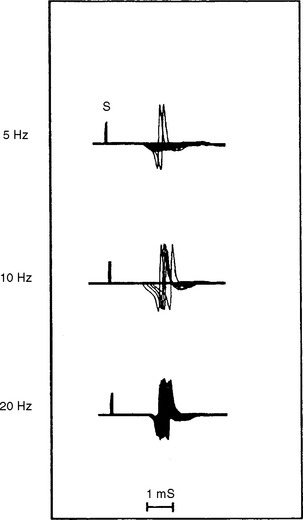

Stimulation Single-Fiber EMG

Stimulation (axonal-stimulated) SFEMG records the jitter between a stimulus artifact and a single potential that is generated by stimulation of a motor unit near the endplate zone. It has the advantage of requiring no patient participation; thus, it may be performed on children, as well as uncooperative or comatose patients. It is performed by inserting another monopolar needle electrode near the intramuscular nerve twigs, and stimulating at a low current and constant rate. The electromyographer has to manipulate two electrodes, a stimulating and recording electrode, until one or more potentials are recorded. The IPI is calculated between the stimulus artifact and a single potential generated by stimulating a motor unit near the endplate zone. Since jitter (MCD) values are calculated on the basis of one endplate, the normal values are lower than those obtained by voluntary activation. To calculate the normal stimulation jitter value, the reference data for voluntary activation are multiplied by 0.80.

In addition to its relative ease in performing, the rate of stimulation can be adjusted from a slow rate (2–5 Hz) to a rapid rate (20–50 Hz). This is helpful in the differentiation of presynaptic and postsynaptic disorders because neuromuscular transmission, jitter and blocking improve significantly with a rapid rate stimulation in LEMS, but it does not change or it worsens in MG (Figure C17-11).

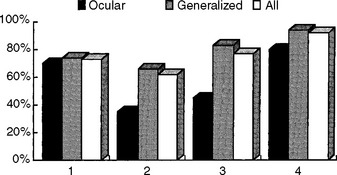

Diagnostic Sensitivity of Electrodiagnostic Tests

In general, the diagnostic utility of the EDX studies correlates well with the severity of MG. The tests are more often abnormal in patients with significant generalized weakness while they may be normal in those with mild ocular disease. The exact sensitivity of the various EDX tests is not known, since there is no gold standard for diagnosis and many seropositive patients are not subjected to these time consuming tests. Using the clinical examination and a positive Tensilon test as a gold standard for the diagnosis of MG, the diagnostic sensitivity of various diagnostic tests is shown in Figure C17-12. Most importantly, it is extremely rare for patients with MG to have an entirely negative work-up that includes repetitive nerve stimulation recording both distal and proximal muscles, single-fiber jitter analysis of an affected muscle, and ACH receptor antibody.

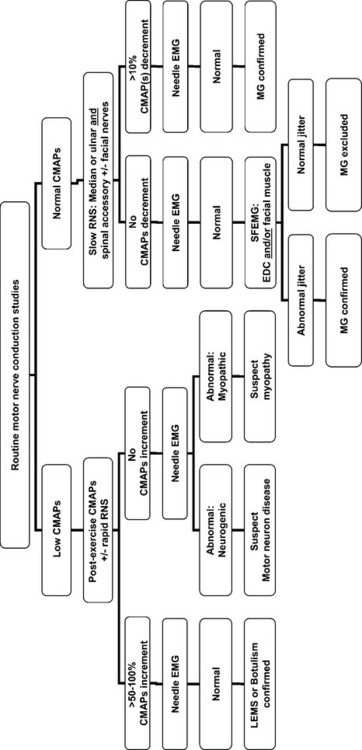

Suggested Electrodiagnostic Work-Up

When a patient is suspected to have MG, routine nerve conduction studies should be performed initially. If the CMAP amplitudes are low, a presynaptic defect should be suspected and excluded, but a postsynaptic defect is surmised if the CMAP amplitudes are normal. Figure C17-13 highlights the proposed EDX work-up for such a patient.

Barberi S, Weiss GM, Daube JR. Fibrillation potentials in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5:S50.

Boonyapisit K, Kaminski HJ, Ruff RL. The molecular basis of neuromuscular transmission disorders. Am J Med. 1999;6:97-113.

Daroff RB. The office Tensilon test for ocular myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:843-844.

Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1797-1810.

Gilchrist JM. Ad hoc committee of the AAEM special interest group on SFEMG. Single fiber EMG reference values: a collaborative effort. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:151-161.

Gilchrist JM. Single fiber EMG. In: Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, Ruff RL, Shapiro EB, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002:141-150.

Howard JH, Sanders DB, Massey JM. The electrodiagnosis of myasthenia gravis and the Lambert-Eaton syndrome. Neurol Clin. 1994;12:305-330.

Kaminski HJ, editor. Myasthenia gravis and related disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2003.

Katirji B, Kaminski HJ. An electrodiagnostic approach to the patient with neuromuscular junction disorder. Neuro Clin. 2002;20:557-586.

Kelly JJ, et al. The laboratory diagnosis of mild myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:238-242.

Kupersmith MJ, Moster M, Bhuiyan S, et al. Beneficial effects of corticosteroids on ocular myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:802-804.

Lanska DJ. Diagnosis of thymoma in myasthenic using anti-striated muscle antibodies. Neurology. 1991;41:520-524.

Lewis RA, Selwa JF, Lisak RP. Myasthenia gravis: immunological mechanisms and immunotherapy. Ann Neurol. 1995;37(S1):S51-S62.

Oh SJ. Electromyography: neuromuscular transmission studies. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1988.

Oh SJ, et al. Electrophysiological and clinical correlation in myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:348-354.

Oh SH, et al. Diagnostic sensitivity of the laboratory tests in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:720-724.

Stalberg E, Trontelj JV. Single fiber electromyography, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Press, 1994.

Tindall RSA, et al. Preliminary results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cyclosporine in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:719-724.

Zinman L, Ng E, Bril V. IV immunoglobulin in patients with myasthenia gravis: A randomized controlled study. Neurology. 2007;68:837-841.