Case 16

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

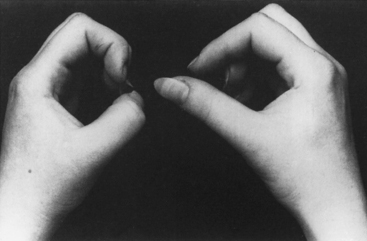

When the patient was seen 4 weeks after the onset of symptoms, he had minimal shoulder pain. Cranial nerve examination was normal. There was no Horner sign. Findings were limited to the right upper extremity, where there was complete loss of function of the right deltoid, spinati, biceps, and brachioradialis (Medical Research Council [MRC] 0/5). The right triceps was much less involved (4/5). There was mild diffuse weakness of all finger and wrist extensors, with severe weakness of the right thumb long flexion (flexor pollicis longus) and distal interphalangeal flexion of the index and middle fingers (flexor digitorum profundus). This resulted in a positive pincer or OK sign (Figure C16-1). Deep tendon reflexes of the right upper limb were absent. Sensation revealed mild sensory loss over the thumb, and lateral arm and forearm.

An electrodiagnostic (EDX) study was performed.

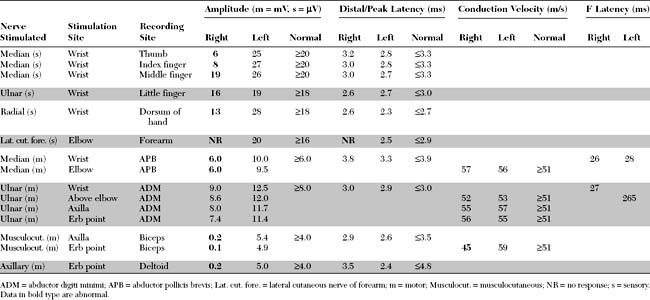

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Abnormalities on EDX examination include:

DISCUSSION

Clinical Features

Neuralgic amyotrophy is likely an immune-mediated disorder that affects peripheral nerves of the upper limb and is not restricted to elements of the brachial plexus. Unfortunately, the disorder is known by several misleading names that result sometimes in misdiagnosis (Table C16-1). Neuralgic amyotrophy has an estimated annual incidence of 1.64 cases per 100 000 population. It most often affects adults, peaking during their twenties. Males are affected twice as often as females. It is usually unilateral, but is sometimes bilateral and asymmetrical; it is occasionally recurrent. Most cases have no specific precipitating factors, but some appear few hours to weeks of an upper respiratory tract infection, a vaccination, childbirth, or an invasive diagnostic, therapeutic or surgical procedure.

Table C16-1 Terms Commonly Used to Describe the Syndrome of Neuralgic Amyotrophy (Listed Alphabetically)

As the most popular name implies, neuralgic amyotrophy is characterized by pain and weakness of the upper limb. The pain is usually abrupt in onset with a tendency to develop at night, sometimes awakening the patient from sleep. It is a severe deep boring shoulder pain, and maximal during the first few days of illness. The pain is not exacerbated by the Valsalva maneuver (e.g., cough, sneeze) which helps distinguishing it from a subacute cervical radiculopathy. Many patients visit the emergency department for pain control. In atypical cases, the pain is only modest and maximal over the antecubital fossa. The pain usually lasts for 7–10 days, gradually fades and becomes replaced by a dull ache.

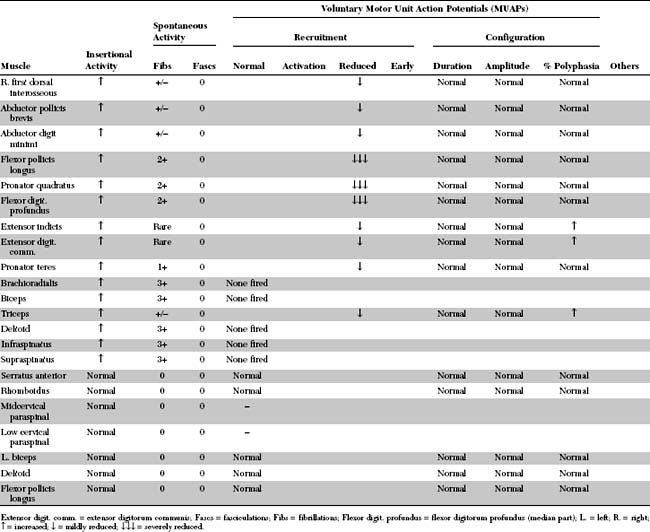

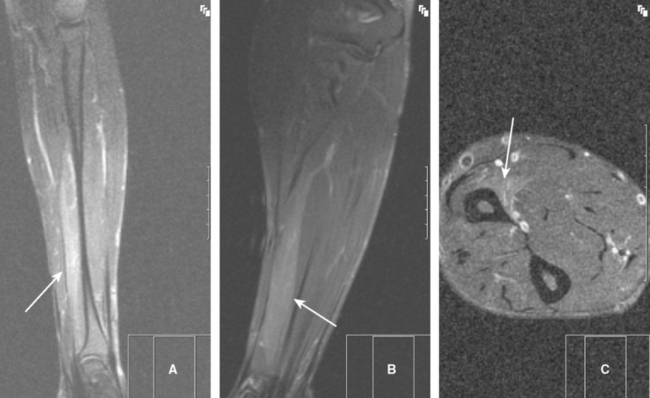

Typically, the patient notices upper limb weakness, and sometimes wasting become apparent, during the first week as the pain starts to subside. Weakness of the shoulder girdle muscles, with or without scapular winging, is the most common since the upper plexus-innervated muscles are usually the most affected. The weakness is often restricted to multiple individual peripheral nerves and sometimes to a single nerve only (Table C16-2). Occasionally, the disorder afflicts the entire brachial plexus or exclusively the lower plexus leading to a near complete monoplegia or distal upper extremity weakness, respectively. Oddly, the main upper limb nerves, i.e., the median, ulnar, and radial nerves, are seldom exclusively affected. Occasionally, selective muscles are selectively denervated, presumably due to pathology of the motor branches. This includes the pronator teres, flexor pollicis longus and supraspinatus muscles (Figure C16-2). Sensory loss usually is mild but may be prominent in severe cases. Deep tendon reflexes are depressed or absent if the appropriate muscles are weakened significantly. Chest radiographs may reveal an elevated hemidiaphragm on the ipsilateral side, due to phrenic nerve palsy. Routine magnetic resonance imaging studies of the brachial plexus or upper limb usually are normal, apart from T2-weighted changes of denervated muscles. The diagnosis frequently is based on the clinical picture and is supported by EDX confirmation.

Table C16-2 Peripheral Nerves With High Predilection to Insult During Neuralgic Amyotrophy (Listed in Order of Frequency of Occurrence)

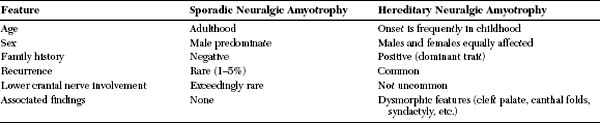

The differential diagnosis of neuralgic amyotrophy is wide and depends upon the particular nerve(s) affected and the specific antecedent event. It includes rotator cuff tears, cervical radiculopathies, traumatic plexopathies, intraoperative nerve damage, and entrapment neuropathies. Pack palsy occasionally is mistaken for neuralgic amyotrophy, but the clinical circumstances and the fact that pain is not a component of its presentation help in distinguishing pack palsy from neuralgic amyotrophy. A familial disorder that is sometimes indistinguishable clinically and electrodiagnostically from the sporadic form of neuralgic amyotrophy occurs, and is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. This disorder is often called hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy, or familial brachial plexus neuropathy and is linked to the distal long arm of chromosomes 17q25, with three mutations in the gene septin 9 identified so far. Certain features tend to help in establishing the diagnosis for these families (Table C16-3). Acute brachial plexopathy may occur after minor trauma in patients with another autosomal dominant disorder, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy (HNPP). However, the plexopathy in HNPP is typically painless and resolves more rapidly. Also, the neurological examination as well as the nerve conduction studies in other limbs often reveal an underlying generalized demyelinating polyneuropathy. The diagnosis is confirmed by detecting deletion of the human peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) gene, located on chromosome 17p11.2-12. Also, if done, pathologic studies of peripheral nerves reveal evidence of segmental demyelination and tomaculous or “sausage-like” formations.

Table C16-3 Distinguishing Features of Sporadic Neuralgic Amyotrophy and Hereditary Neuralgic Amyotrophy

| Feature | Sporadic Neuralgic Amyotrophy | Hereditary Neuralgic Amyotrophy |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Adulthood | Onset is frequently in childhood |

| Sex | Male predominate | Males and females equally affected |

| Family history | Negative | Positive (dominant trait) |

| Recurrence | Rare (1–5%) | Common |

| Lower cranial nerve involvement | Exceedingly rare | Not uncommon |

| Associated findings | None | Dysmorphic features (cleft palate, canthal folds, syndactyly, etc.) |

Electrodiagnosis

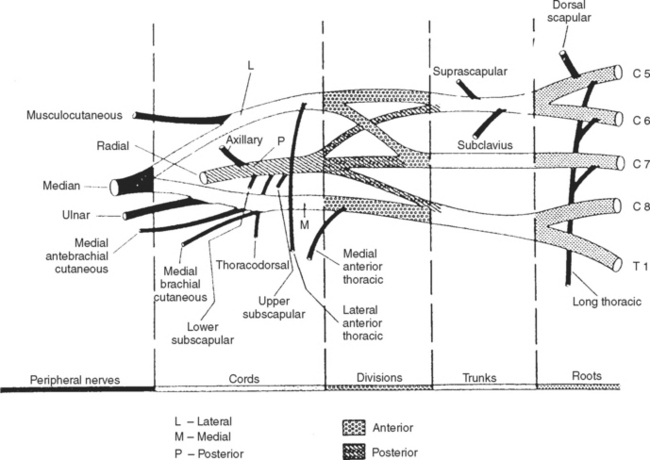

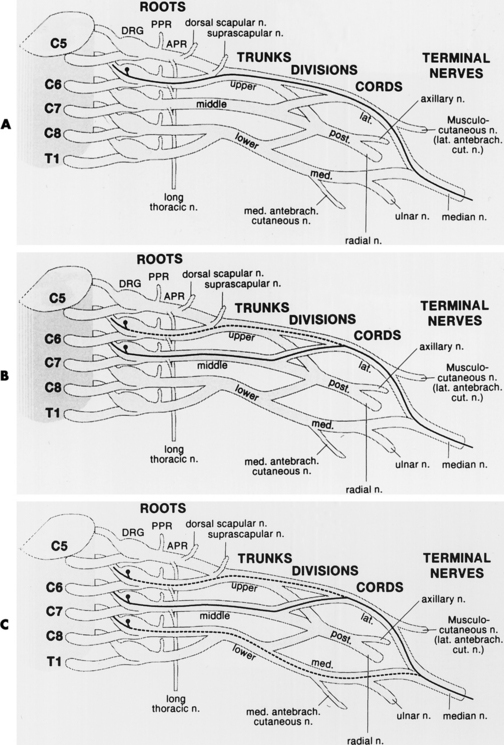

In assessing a patient with possible neuralgic amyotrophy, the electromyographer should have a firm grasp of the anatomy of the brachial plexus and its branches (Figure C16-3), as well as the peripheral nerves of the upper extremity (Table C16-4) and the myotomal chart of all muscles of the upper limb (see Figure C11–6). Three important anatomical facts must be emphasized in localizing lesions of the brachial plexus:

Table C16-4 Motor and Sensory Nerves Arising Directly from the Brachial Plexus (excluding the main terminal nerves)

Brachial plexus lesions are divided into supraclavicular and infraclavicular plexopathies. Supraclavicular plexus lesions are further divided into the upper trunk, middle trunk, and lower trunk lesions. Infraclavicular lesions are divided into lateral cord, posterior cord and medial cord lesions. The electrodiagnosis of lesions of the brachial plexus, the largest and most complex structures of the peripheral nervous system, is more time consuming and requires performing multiple common and uncommon sensory and motor nerve conduction studies and sampling a large number of muscles with needle EMG. In lesions of the brachial plexus that are restricted to a specific trunk or cord, certain sensory and motor NCSs and muscles are likely to be abnormal based on the location of the injured fibers within the plexus (Tables C16-5 and C16-6).

Table C16-5 Nerve Conduction Studies and Muscles Commonly Affected in Upper Brachial Plexus Lesions

| Sensory Conduction Studies | Motor Conduction Studies | Needle EMG |

|---|---|---|

Adapted with revisions from Wilbourn AJ. Assessment of the brachial plexus and the phrenic nerve. In: Johnson EW, Pease W, eds. Practical electromyog-raphy, 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, 1997.

Table C16-6 Nerve Conduction Studies and Muscles Commonly Affected in Lower Brachial Plexus Lesions

| Sensory Conduction Studies | Motor Conduction Studies | Needle EMG |

|---|---|---|

* These include the abductor pollicis brevis, the first dorsal interosseous (and all other interossei), the adductor pollicis, and the abductor digiti minimi.

Adapted with revisions from Wilbourn AJ. Assessment of the brachial plexus and the phrenic nerve. In: Johnson EW, Pease W, eds. Practical electromyog-raphy, 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, 1997.

Needle examination frequently is more impressively abnormal than the nerve conduction studies. Fibrillations and decreased recruitment of motor unit action potential (MUAP) consistent with denervation are more extensive than is evident by clinical examination. The MUAPs become polyphasic and increased in duration as sprouting proceeds after one to two months from illness onset. The findings frequently are patchy, and they often do not conform to specific root or peripheral nerve distribution. At times, EMG findings in patients with shoulder girdle weakness suggest that the disorder is caused by lesions of multiple individual peripheral nerves (mononeuropathies) rather than of the upper plexus.

Certain EDX findings, when present, are highly suggestive of neuralgic amyotrophy. These include:

Airaksinen EM, et al. Hereditary recurrent brachial plexus neuropathy with dysmorphic features. Acta Neurol Scand. 1985;71:309-316.

Beghi E, et al. Brachial plexus neuropathy in the population of Rochester, Minnesota, 1970–1981. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:320-323.

England JD, Sumner AJ. Neuralgic amyotrophy: an increasingly diverse entity. Muscle Nerve. 1987;10:60-68.

Flagman PD, Kelly JJ. Brachial plexus neuropathy. An electrophysiologic evaluation. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:160-164.

Katirji B. Subacute lower brachial plexopathy: another form of neuralgic amyotrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1642.

Malamut RI, et al. Postsurgical idiopathic brachial neuritis. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:320-324.

Parsonage MJ, Turner AJW. Neuralgic amyotrophy: the shoulder-girdle syndrome. Lancet. 1948;1:973-978.

Spillane JD. Localized neuritis of the shoulder girdle. Lancet. 1943;2:532-535.

Tsairis P, Dyck PJ, Mulder DW. Natural history of brachial plexus neuropathy; report of 99 cases. Arch Neurol. 1972;27:109-117.

Vanneste JA, Bronner IM, Laman DM, et al. Distal neuralgic amyotrophy. J Neurol. 1999;246:399-402.

Weikers NJ, Mattson RH. Acute paralytic brachial neuritis: a clinical and electrodiagnostic study. Neurology. 1969;19:1153-1158.

Wilbourn AJ. Assessment of the brachial plexus and the phrenic nerve. In Johnson EW, Pease W, editors: Practical electromyography, 3rd ed., Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins, 1997.