Case 14

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination was performed.

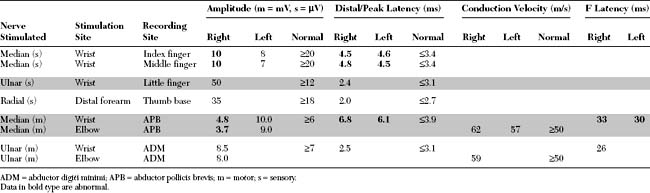

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Relevant EDX findings in this patient include:

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

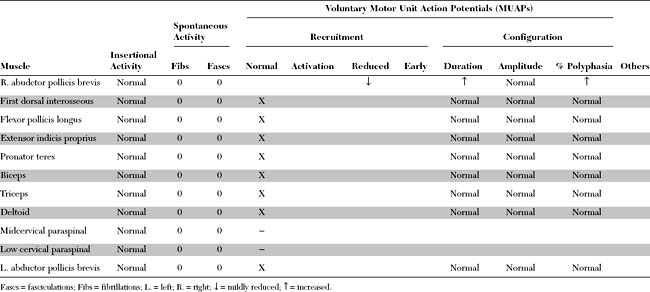

The median nerve is one of the main terminal nerves of the brachial plexus, formed by contributions from the lateral and medial cords (Figure C14-1). The lateral cord component, comprised of C6–C7 fibers, provides sensory fibers to the thumb and thenar eminence (C6), index finger (C6–C7), and middle finger (C7) and motor fibers to the proximal median innervated forearm muscles. The medial cord component, comprised of C8–T1 fibers, provides sensory fibers to the lateral half of the ring finger (C8) and motor fibers to the hand and distal median innervated forearm muscles.

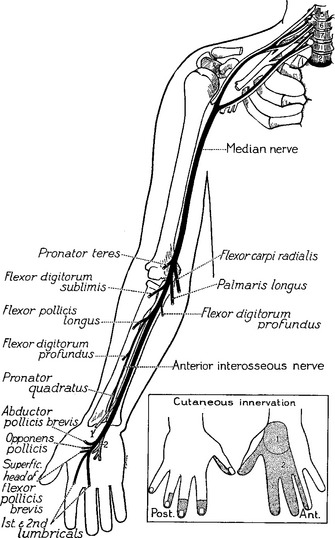

Right before entering the wrist, the median nerve gives off its first cutaneous branch, the palmar cutaneous branch, which runs subcutaneously (does not pass through the carpal tunnel) and innervates a small patch of skin over the base of the thumb and the thenar eminence (see Figure C14-1). Then, the main trunk of the median nerve, along with nine finger flexor tendons, enters the wrist through the carpal tunnel. The carpal bones form the floor and sides of the tunnel while the carpal transverse ligament, which is attached to the scaphoid, trapezoid, and hamate bones, forms its roof (Figure C14-2). The carpal tunnel cross-section is variable but is approximately 2.0 to 2.5 cm at its narrowest point in most individuals.

Clinical Features

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common entrapment neuropathy. It is slightly more common in women and usually involves the dominant hand first. It is most prevalent after 50 years of age, but it may occur in younger patients, especially in association with pregnancy and certain occupations or medical conditions. Most cases of CTS are idiopathic, but many are associated with disorders that decrease the carpal tunnel space or increase the susceptibility of the nerve to pressure. Among the medical conditions with a high risk for CTS are pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, acromegaly, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and amyloidosis. Some patients have congenitally small carpal tunnels, while others have anomalous muscles, wrist fractures (Colles or carpal bone), or space occupying lesions (ganglia, lipoma, schwannoma). Occupational CTS, which has reached a near-epidemic level in the industrial world, is seen in patients whose jobs involve repetitive movements of the wrists and fingers. Although most cases of CTS are subacute or chronic in nature, it occasionally may be acute, such as after crush injury of the hand, fracture (Colles or carpal bone), or acute tenosynovitis.

The differential diagnoses of CTS include:

Electrodiagnosis

Nerve Conduction Studies: Comparison Studies

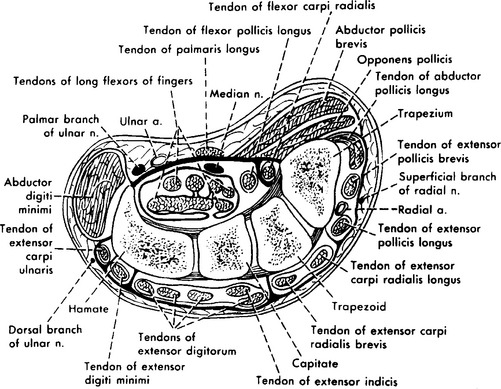

It is now evident that the median motor and median sensory distal latencies are not sensitive enough in the diagnosis of CTS. Relying on these measurements only will fail to detect a significant number (up to one-third) of patients with mild CTS, particularly those with symptoms precipitated by certain hand activities (e.g., drilling, typing, etc.). In addition, as the syndrome has become well known to the medical community and to the general public, it has become common practice for EMG laboratories to test patients with very early symptoms of CTS. This has resulted in the design of several NCSs with higher sensitivity and specificity than the routine median sensory and motor studies (Table C14-1). These techniques rely on one or both of the following approaches:

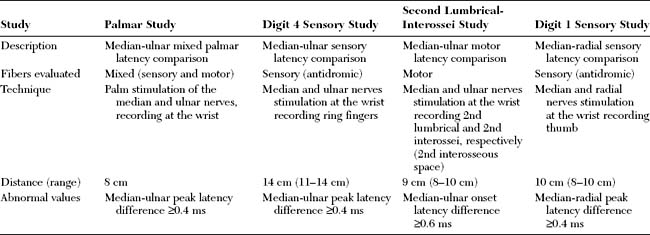

Table C14-1 Nerve Conduction Studies in the Diagnosis of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Table C14-2 lists and Figure C14-3 shows the most common internal comparison NCSs used in the diagnosis of CTS. Most of these procedures yield abnormal findings in symptomatic patients. However, the absence of a gold standard for the diagnosis of CTS precludes the determination of sensitivity, specificity, or predictive value for any of these tests. Applying these sensitive techniques in combination increases the diagnostic yield of EDX testing in the diagnosis of CTS to approximately 95%.

Table C14-2 Internal Comparison Nerve Conduction Studies in the Evaluation of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS)

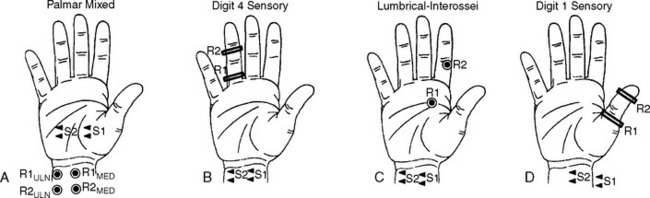

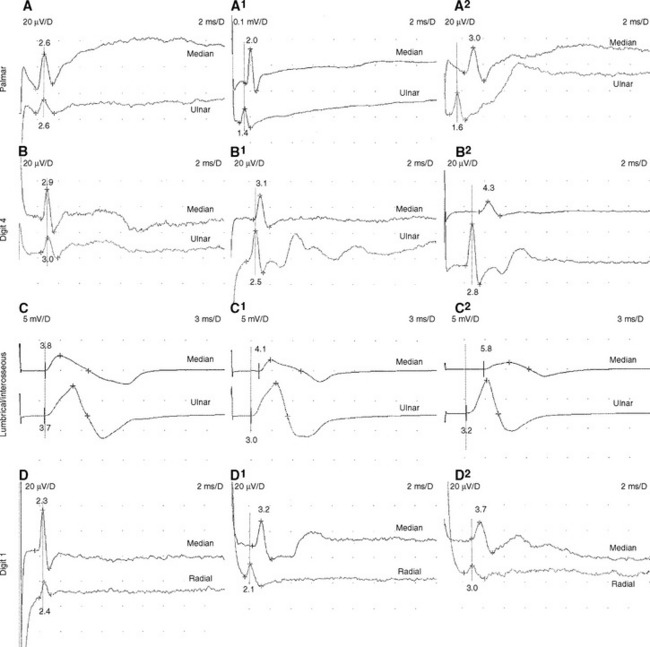

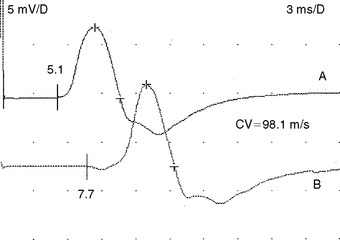

Median-Ulnar Palmar Mixed Latency Difference “Palmar Study”

Trans-palmar mixed nerve conduction studies involve the elicitation of focal slowing of the median nerve between the palm and the wrist. Although abnormal absolute values were first considered to be a satisfactory indication in the diagnosis of CTS, comparison of median to ulnar latency with palmar stimulation has proved to be more sensitive and specific. The median nerve is stimulated in the midpalm between the second and third metacarpals, and the ulnar nerve is stimulated between the fourth and fifth metacarpals. Recording occurs at the wrist over the median and ulnar nerves 8 cm proximal to the midpalm cathode (Figure C14-3A). Extreme care must be given to measurements of nerve segments and latency analyses to prevent false-negative and false-positive results. Initial reports suggested that a median-ulnar palmar difference of greater than or equal to 0.2 ms is diagnostic of CTS; however, recent studies suggest that a difference of greater than or equal to 0.4 ms is needed for confirmation to prevent false-positive results (Figure C14-4A, A1, and A2). A median-ulnar difference of 0.2 to 0.3 ms is considered borderline. It is estimated that palmar studies are abnormal in about 80% of symptomatic hands with CTS. In all published studies of CTS, palmar mixed nerve studies were far superior to the routine median sensory distal latency between the wrist and digit (index or middle finger).

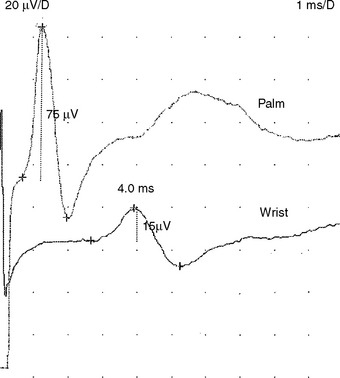

Median-Ulnar Sensory Latency Difference Between the Wrist and the Ring Finger

In this study, the median and ulnar sensory distal latencies recording the ring finger are compared. When the technique is performed antidromically at a 11 to 14 cm distance (Figure C14-3B), the difference in peak latencies of greater than or equal to 0.4 ms is abnormal (Figure C14-4, B, B1, and B2). This test is abnormal 80 to 90% of patients with CTS. Its only disadvantage is that the median or ulnar SNAPs may be low in amplitude and difficult to evoke, due to the variable sensory innervation of the ring finger. When done orthodromically, the response in patients with CTS has a double hump, the first peak reflecting the volume-conducted ulnar fibers, and the second peak reflecting the slowed median fibers. It is preferable, in this situation, to also record over the ulnar nerve at the wrist to confirm that the first peak represents the ulnar fibers.

Median-Ulnar Motor Latency Difference Recording the Second Lumbrical/Interossei

This motor study compares the distal motor latency of the median nerve, recording the second lumbrical muscle, to the ulnar motor latency, recording the second intersossei. The recording surface electrode is placed just lateral to the midpoint of a line over the third metacarpal bone that connects the base of the middle finger to the middle of the distal wrist crease. The reference electrode is placed over the second proximal interphalangeal joint (Figure C14-3C). The lumbrical and interosseous CMAPs are recorded when the median and ulnar nerves are stimulated at the wrist, respectively. If a standard and equal distance of 8–10 cm is used for both nerves, a median-ulnar distal latency difference of greater than or equal to 0.6 ms is consistent with CTS (Figure C14-4C, C1 and C2). This technique has several advantages: (1) the motor responses are generally more easily recorded than sensory responses; (2) this study is able to localize the lesion to the wrist in over 90% of cases of severe CTS resulting in absent routine median CMAPs and SNAPs; and (3) this study can still be easily performed in patients with CTS and advanced polyneuropathy associated with absent sensory responses in the hands.

Median-Radial Sensory Latency Difference Between the Wrist and the Thumb

This technique compares the distal sensory latency of the median nerve to the latency of the radial nerve while the thumb is recorded (Figure C14-3D). This can be performed antidromically or orthodromically, but can be difficult to perform because of movement or stimulus artifacts. At an 8–10 cm distance, a difference of greater than or equal to 0.4 ms of peak latencies is considered abnormal (Figure C14-4D, D1, and D2). This study is abnormal in about 80% of hands with CTS.

Other tests have been advocated but that have not proved to be superior nor specific for CTS and have no localizing value. This includes assessment for fibrillation potentials, myokymia, or chronic neurogenic changes of the thenar muscles, and delay of median minimal F wave latencies when compared to the ulnar minimal F wave latencies.

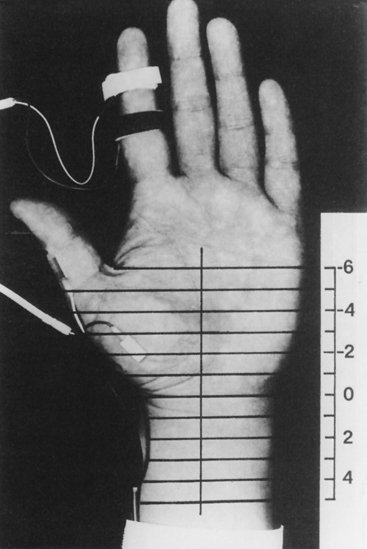

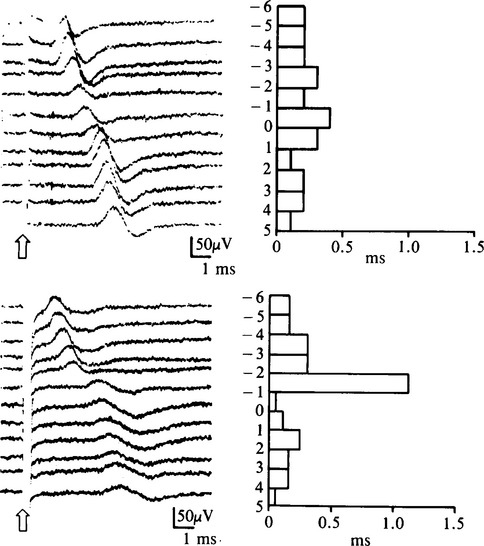

Segmental Nerve Conduction Studies: “Inching” Studies

These studies, described by Kimura, consist of serial stimulations in 1 cm increments of the median nerve from the mid-palm to the distal forearm, recording antidromically from the index or middle finger (Figure C14-5). There usually is a latency change of 0.16 to 0.21 ms/cm between stimulation sites. In patients with CTS, there is an abrupt latency increase of greater than 0.4 to 0.5 ms across one or two adjoining segments (Figure C14-6). This most often occurs 2 to 4 cm distal to the distal wrist crease, the latter corresponding to the origin of the transverse carpal ligament. Although it is time consuming and subject to error (measurement error and volume conduction), the sensory study precisely localizes the lesion in more than 80% of symptomatic hands. Similar incremental study of the median nerve across the carpal tunnel, recording the abductor pollicis brevis, is also possible. However, unlike the sensory fibers, the median motor fibers are difficult to activate sequentially in 1 cm intervals because of the recurrent course of the motor branch to the thenar muscles; hence, the response is frequently contaminated by stimulus artifact because of the proximity of the recording electrode to the stimulating cathode.

Figure C14-6 The inching technique in a patient with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) (top is asymptomatic hand and bottom is symptomatic hand). The left side of the figure shows the results of 12 antidromically recorded sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs), as shown in Figure C14-5. The right side of the figure graphs the successive time difference between traces.

(From Kimura J. The carpal tunnel syndrome. Localization of conduction abnormalities within the distal segment of the median nerve. Brain 1979;102:619–635, with permission.)

Needle EMG

Needle EMG examination in patients with CTS has two objectives:

Special Situations

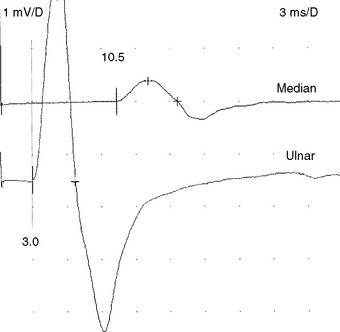

Severe Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

In severe CTS, which is more common in elderly patients, absent median sensory NCS, recording all digits, and median motor NCS, recording APB, is not uncommon. This renders EDX localization of the median nerve lesion to the wrist not possible, despite classic manifestations. Traditionally, these lesions were poorly localized, by needle EMG only, at or above the wrist. In these situations, the sensory and mixed internal comparison studies are equally absent. However, the second lumbrical-interosseous motor comparison study confirms the lesion at the wrist in more than 90% of cases by revealing that the median motor response recording second lumbrical is still evokable often with marked slowing of median distal latency (Figure C14-7). The relative preservation of the motor fibers to the lumbrical muscles as compared to the thenar muscles is best explained by the fascicular distribution of the median nerve fibers within the carpal tunnel: Fibers to the lumbrical muscles, which are more centrally located, tend to be relatively spared from axonal loss late in the course of the disease while the motor fibers to the thenar muscles, as well the sensory fibers, located in the periphery of the nerve, are destroyed earlier.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome With Peripheral Polyneuropathy

Carpal tunnel syndrome coexists not uncommonly in patients with underlying peripheral polyneuropathy, such as with diabetes. In mild axonal polyneuropathies, where the SNAPs in the hands are still recorded though low in amplitudes and delayed in latencies, sensory, motor, or mixed nerve internal comparison studies are useful in showing the preferential slowing of the median fibers at the wrist due to entrapment at the carpal tunnel. In instances of severe axonal polyneuropathy, where the SNAPs are often absent in the hands, the second lumbrical-interosseous motor comparison study is the most accurate by demonstrating preferential focal slowing of median motor fibers across the carpal tunnel. In all axonal polyneuropathy cases, selective large fiber axon loss may cause slowing; hence, borderline or minimal latency differences on internal comparison studies should be cautiously interpreted.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome With Martin-Gruber Anastomosis

Carpal tunnel syndrome occasionally occurs in a patient with Martin-Gruber anastomosis, an anomalous connection between the median and the ulnar nerves in the forearm (see Chapter 2). When the anomalous fibers innervate the thenar muscles (usually adductor pollicis and deep head of flexor pollicis brevis), stimulation of the median nerve at the elbow activates the median nerve and the crossing ulnar fibers resulting in a large CMAP, with an initial positivity caused by volume conduction of action potential from ulnar thenar muscles to the median thenar muscles. This positive dip is not present at the wrist. Also, the median nerve conduction velocity in the forearm is spuriously fast in the presence of a CTS, since the CMAP onset represents different population of fibers at the wrist compared to the elbow (Figure C14-8). An accurate conduction velocity may be obtained by using specialized collision studies that abolish action potentials of the crossed fibers.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Pregnancy

Up to 60% of pregnant women have nocturnal hand symptoms, most frequently during the third trimester of pregnancy, while the incidence of confirmed pregnancy-related CTS is about 40%. Limb edema is a significant predictor for CTS during pregnancy. Symptoms resolve in most patients after delivery, while patients with significant weight gain, limb edema, or symptom onset during early pregnancy have lower probability for complete resolution. Treatment is usually conservative including wrist splinting, corticosteroid injections, and oral diuretics. Most patients do not require EDX testing since symptoms usually resolve after delivery within 4–6 weeks.

When EDX studies are done during pregnancy, the pathophysiology in these patients is often median nerve demyelination resulting in focal slowing with or without conduction block across the wrist. In many of these cases, the routine NCSs reveal only slowing of distal latencies on routine or comparison studies. Some cases show low median motor or sensory amplitudes stimulating at the wrist, which may signify secondary axonal loss, conduction block, or a combination. The presence of conduction block can be confirmed by comparing motor and sensory amplitudes with stimulation at the wrist and in the palm (Figure C14-9). Palm stimulation of the median nerve recording the index or middle finger (sensory) or thenar muscles (motor) may be technically difficult because of shock artifact due to close proximity between the stimulating and recording electrodes. Due to normal (physiologic) temporal dispersion and phase cancellation of SNAP more than CMAP, median conduction block across the wrist should only be diagnosed when the drop of amplitudes exceeds 20% for median CMAPs and 40% for median SNAPs. The conduction block and slowing often resolves soon after delivery.

Al-Shekhlee A, Fernandes-Filho A, Sukul D, et al. Optimal G1 placement in the lumbrical interosseous latency comparison study. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:289-293.

Boonyapisit K, Katirji B, Shapiro BE, et al. Lumbrical and interossei recording in severe carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:102-105.

Daube JR. Percutaneous palmar median nerve stimulation for carpal tunnel syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1977;43:139-140.

Gelberman RH, Aronson D, Weisman MH. Carpal tunnel syndrome: results of a prospective trial of steroid injection and splinting. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;52:253-255.

Giannini F, et al. Electrophysiologic evaluation of local steroid injection in carpal tunnel syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:738-742.

Eogan M, O’Brien C, Carolan D, et al. Median and ulnar nerve conduction in pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;87:233-236.

Herskovitz S, Berger AR, Lipton RB. Low-dose, short-term oral prednisone in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 1995;45:1923-1925.

Hui ACF, Wong S, Leung CH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of surgery vs steroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 2005;64:2074-2078.

Jablecki CK, et al. Literature review of the usefulness of nerve conduction studies and electromyography for the evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1392-1414.

Jackson D, Clifford JC. Electrodiagnosis of mild carpal tunnel syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70:199-204.

Kimura J. The carpal tunnel syndrome. Localization of conduction abnormalities within the distal segment of the median nerve. Brain. 1979;102:619-635.

Lesser EA, Venkatesh S, Preston DC, et al. Stimulation distal to the lesion in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:503-507.

Logigian EL, Busis NA, Berger AR, et al. Lumbrical sparing in carpal tunnel syndrome: anatomic, physiologic, and diagnostic implications. Neurology. 1987;37:1499-1505.

Loscher WN, Auer Grumbach M, Trinka E, et al. Comparison of second lumbrical and interosseous latencies with standard measures of median nerve function across the carpal tunnel: a prospective study of 450 hands. J Neurol. 2000;247:530-534.

McConnell JR, Bush DC. Intraneural steroid injection as a complication in the management of carpal tunnel syndrome: a report of three cases. Clin Orthop. 1990;250:181-184.

Nathan PA, Meadows KD, Doyle LS. Sensory segmental latency values of the median nerve for a population of normal individuals. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:499-501.

Padua L, Aprile I, Caliandro P, et al. Symptoms and neurophysiological picture of carpal tunnel syndrome in pregnancy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1946-1951.

Padua L, Aprile I, Caliandro P, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome in pregnancy: multiperspective follow-up of untreated cases. Neurology. 2002;59:1643-1646.

Pease WS, Cannell CD, Johnson EW. Median to radial latency difference test in mild carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:905-909.

Phalen GS. The carpal tunnel syndrome: seventeen years’ experience in diagnosis and treatment of six hundred and fifty-four hands. J Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48:211-228.

Preston DC, Logigian EL. Lumbrical and interossei recording in carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:1253-1257.

Preston DC, Ross MH, Kothari MJ, et al. The median-ulnar latency difference studies are comparable in mild carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:1469-1471.

Redmond MD, Rivner MH. False positive electrodiagnostic tests in carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:511-518.

Report of the Quality Standards Sub-Committee of the American Academy of Neurology: practice parameter for carpal tunnel syndrome (summary statement). Neurology. 1993;43:2406-2409.

Rosenbaum RB, Ochoa JL. Carpal tunnel syndrome and other disorders of the median nerve, 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier, 2002.

Schuchmann JA, et al. Evaluation of local steroid injection in carpal tunnel syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1971;52:253-255.

Stevens JC. The electrodiagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1987;2:99-113.

Stevens JC, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome in Rochester, MN, 1961–1980. Neurology. 1988;38:134-138.

Ubogu EE, Benatar M. Electrodiagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome in axonal polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:747-752.

Uncini A, Lange DJ, Solomon M, et al. Ring finger testing in carpal tunnel syndrome: a comparative study of diagnostic utility. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:735.

Wong S, Hui ACF, Tang A, et al. Local vs systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:1565-1567.