Case 13

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A cervical spine radiograph showed a rudimentary cervical rib on the right (Figure C13-1). An EMG examination was performed.

Figure C13-1 The patient’s cervical spine x-ray (anteroposterior view) revealing a rudimentary cervical rib on the right (arrow).

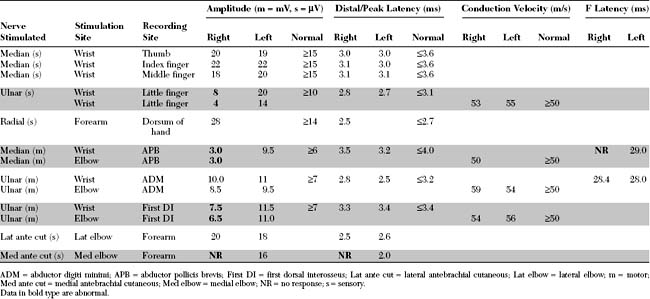

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

The significant EDX findings in this case include the following:

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

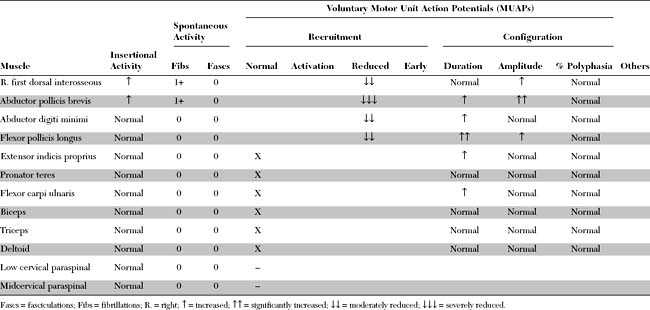

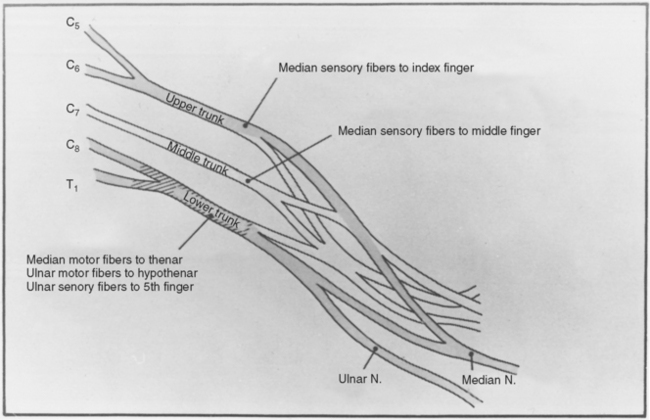

The brachial plexus is derived from the anterior primary rami of the C5 through T1 spinal roots. As is shown in Figure C13-2, these roots intertangle at multiple sites to form structures that usually are divided into five components: roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and peripheral (terminal) nerves. Because the divisions generally are located under the clavicle, some divide the brachial plexus into two regions: supraclavicular (roots and trunks) and infraclavicular (cords and peripheral nerves). Nerve fibers from the C5 and C6 anterior primary rami combine to form the upper trunk, C8 and T1 rami combine to form the lower trunk, and the C7 ramus continues as the middle trunk. Then, each trunk divides into two divisions (anterior and posterior). All three posterior divisions unite to form the posterior cord, the upper two anterior divisions merge to form the lateral cord, and the anterior division of the lower trunk continues as the medial cord.

The terminal peripheral nerves are the main branches that extend from the brachial plexus to the upper limb. From each cord, two major nerves arise: the posterior cord gives rise to the radial and axillary nerves, the lateral cord gives rise to the musculocutaneous nerve and to the lateral half of the median nerve, and the medial cord divides into the ulnar nerve and the medial half of the median nerve.

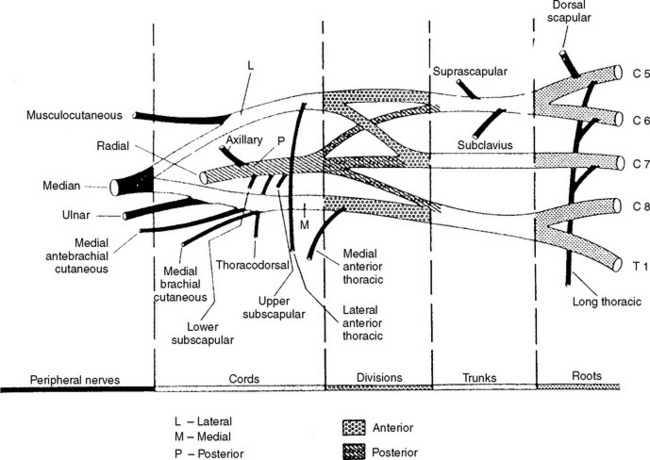

In addition to the terminal nerves, many nerves branch directly from the main component of the brachial plexus. Except for four supraclavicular nerves, all others originate from the cords (i.e., they are infraclavicular). Except for two pure sensory nerves, all others are pure motor, and they innervate the shoulder girdle muscles. Table C13-1 lists these nerves, as they are shown in Figure C13-2, with their origin, function, destination, and segmental innervation.

Clinical Features

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a disorder characterized by compression of the subclavian artery, subclavian vein, or brachial plexus separately or, rarely, in combination. This compression results in a vascular or neurogenic syndrome, depending on which structure is involved. Neurogenic TOS is a neurologic syndrome caused by compression of the lower brachial plexus. Because controversy regarding this syndrome has increased during the past few decades, some have separated neurogenic TOS into true and disputed forms (see Wilbourn 1999).

True neurogenic TOS is a rare, unilateral disorder, which affects mainly young or middle age women. The typical patient presents with wasting and weakness of one hand. There is often several years’ history of hand cramps or mild pain and paresthesias in the medial aspect of the arm, forearm and hand, both exacerbated by physical activity of the upper extremity. On examination, there is atrophy and weakness of the thenar muscles with less involvement of the hypothenar and other intrinsic hand muscles. A patchy sensory loss usually may be present along the medial arm, forearm and hand.

Most patients have a cervical rib or elongated C7 transverse process, with a translucent band extending from it to the first rib. Rarely, classical neurogenic TOS may be caused by compression by structures other than a cervical rib or band, such as a hypertrophied anterior scalenus muscle in a competitive swimmer. In most patients, cervical spine radiographs typically show a cervical rib, a rudimentary cervical rib (see Figure C13-1), or simply an elongated C7 transverse process. In these cases, surgical section of the cervical rib or band (which connects the rudimentary rib or C7 transverse process to the first rib), preferably by a supraclavicular approach, halts the progression of symptoms but does not reverse the hand atrophy or weakness, or the nerve conduction abnormalities.

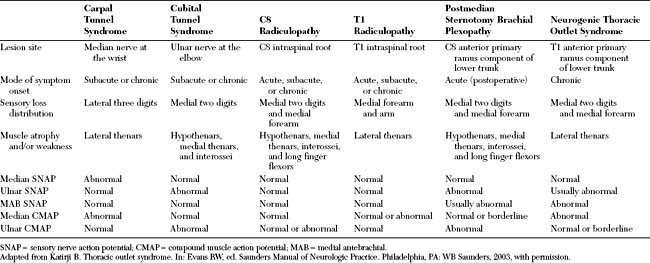

True neurogenic TOS should be distinguished from carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, poststernotomy brachial plexopathy and C8 and T1 radiculopathies (Table C13-2). Occasionally, neurogenic TOS may be confused with monomelic amyotrophy and motor neuron disease.

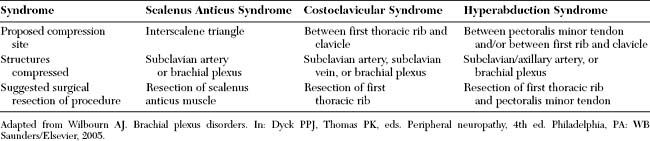

Table C13-3 Three Disputed Syndromes Associated With Neurovascular Compression in the Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

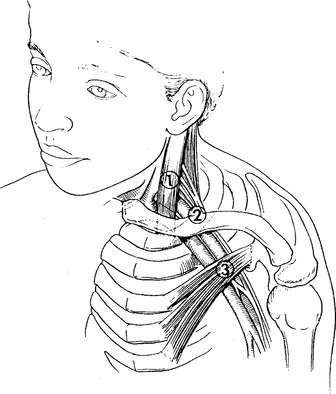

Figure C13-3 The presumed sites of compression within the cervicoaxillary canal for the (1) scalenus anticus syndrome (interscalene triangle); (2) the costoclavicular syndrome (between the first rib and clavicle); and (3) the hyperabduction syndrome (beneath the pectoralis minor tendon). See also Table C13-3.

(From Wilbourn AJ. Brachial plexus disorders. In: Dyck PPJ, Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral neuropathy, 4rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders/Elsevier, 2005.)

Electrodiagnosis

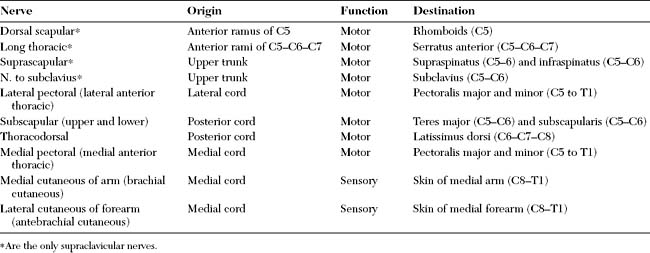

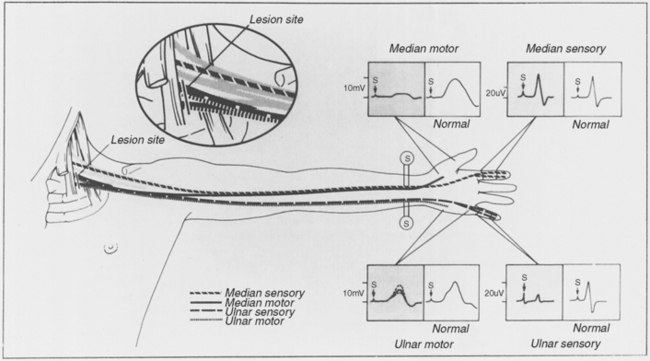

Electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination is the most useful and objective diagnostic procedure in the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. Neurogenic TOS is the result of chronic compression and chronic axon-loss of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, particularly fibers within the T1 anterior primary ramus. Because all ulnar sensory fibers, all ulnar motor fibers, and the C8/T1 median fibers course the lower trunk, they are among the most obviously noted abnormalities on routine NCS. Hence, the EDX findings on nerve conduction studies (NCS) and needle EMG in neurogenic TOS have a very characteristic combination of changes (Table C13-4 and Figures C13-4 and C13-5).

Table C13-4 Findings on Nerve Conduction Studies That Highly Suggest True Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Figure C13-4 Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome showing the site of compression by the cervical rib or band.

(From Wilbourn AJ. Controversies regarding thoracic outlet syndrome: syllabus on controversies in entrapment neuropathies. Rochester, MN: American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 1984, with permission.)

Figure C13-5 Routine nerve conduction abnormalities (median and ulnar nerves) with neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS).

(From Wilbourn AJ. Case report #7: true neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Rochester, MN: American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 1982, with permission.)

The medial antebrachial cutaneous SNAP, a sensory nerve that originates directly from the brachial plexus (medial cord) and innervates the skin of the medial forearm, is now an integral part of the EDX evaluation of patients with suspected neurogenic TOS as well as all other lower brachial plexopathies. An absent or low-amplitude medial antebrachial cutaneous SNAP is a universal finding in all confirmed cases of neurogenic TOS, including the mild cases, in which thenar atrophy is subtle and an ulnar nerve lesion is also considered in the diagnosis.

The EDX findings in neurogenic TOS should be distinguished from a variety of focal neurogenic disorders that may afflict the hand (see Table C13-2). Among these, brachial plexopathy following median sternotomy, a condition that follows cardiac surgery, particularly coronary artery bypass graft and cardiac valve repair, is the most challenging. When the anterior thorax is opened during median sternotomy, the very proximal portion of the first thoracic rib is fractured which, in turn, damages the lower trunk fibers of the brachial plexus situated immediately superiorly. In fact, most of the damage occurs at the level of the C8 anterior primary ramus with little or no involvement of T1 anterior primary ramus. Although neurogenic TOS and brachial plexopathy following median sternotomy are both practically lower trunk plexopathies, these two lesions often have different predilection to fibers forming the lower trunk: T1 fibers in TOS and C8 fibers in brachial plexopathy following median sternotomy. Hence, the abductor pollicis brevis and the medial antebrachial SNAP are the most abnormal in neurogenic TOS while the ulnar C8 innervated muscles and ulnar SNAP are preferentially abnormal in brachial plexopathy due to median sternotomy.

Before concluding, the issue of “ulnar nerve slowing across Erb point” must be addressed. Many clinicians, particularly surgeons, ask electromyographers to look for slowing across the thoracic outlet in patients with suspected neurogenic TOS. This seems to be more commonly requested in patients with pain and sensory symptoms, but no objective neurologic findings on examination (disputed TOS). These data come from a few studies done in the 1970s, in which claims of slowing of conduction were documented in patients with neurogenic TOS. Specifically, the authors claimed that there is focal slowing of the ulnar nerve between Erb point and axillary stimulations, recording the abductor digiti minimi (see Urschel et al. 1971). This finding has been duplicated infrequently by electromyographers. Thus, most electromyographers, including this author, have concluded that focal slowing across the brachial plexus is not a feature of neurogenic TOS.

Ferrante MA, Wilbourn AJ. The utility of various sensory conduction responses in assessing brachial plexopathies. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:879-889.

Gilliatt RW, et al. Wasting of the hand associated with a cervical rib or band. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1970;33:615-624.

Gilliatt RW, et al. Peripheral nerve conduction in patients with a cervical rib and band. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:124-129.

Hardy RW, Wilbourn AJ, Hanson M. Surgical treatment of compressive cervical band. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:10-13.

Howell CMH. A consideration of some symptoms which may be produced by seventh cervical ribs. Lancet. 1907;1:1702-1707.

Katirji B, Hardy RW. Classic neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome in a competitive swimmer: a true scalenus anticus syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:229-233.

Levin KH, Wilbourn AJ, Maggiano HJ. Cervical rib and median sternotomy-related brachial plexopathies: a reassessment. Neurology. 1998;50:1407-1413.

Nishida T, Price SJ, Minieka MM. Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve conduction in true neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;33:285-288.

Roos DB, Wilbourn AJ. Issues and opinions: thoracic outlet syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:126-138.

Thorburn W. The seventh cervical rib and its effects upon the brachial plexus. Med Chir Trans. 1905;88:105.

Urschel HC, et al. Objective diagnosis (ulnar nerve conduction velocity) and current therapy of the thoracic outlet syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;12:608-620.

Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic outlet syndrome surgery causing severe brachial plexopathy. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:66-74.

Wilbourn AJ. Thoracic outlet syndromes. Neurol Clin N Am. 1999;17:477-495.

Wilbourn AJ. Brachial plexus disorders. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral neuropathy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders/Elsevier; 2005:1359-1360. 1370–1371