Case 12

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

EMG examination was done 5 weeks postinjury.

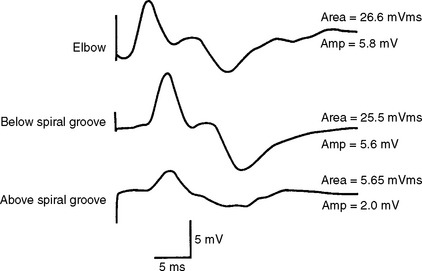

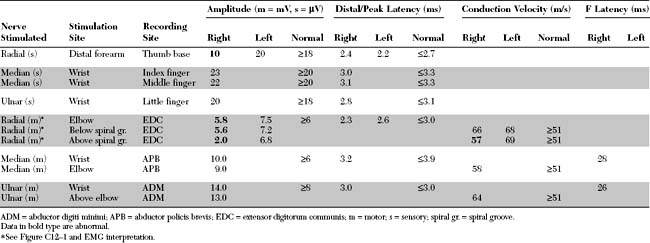

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS) and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Abnormal EDX findings include:

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

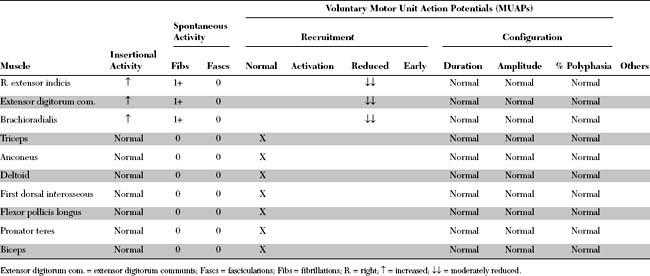

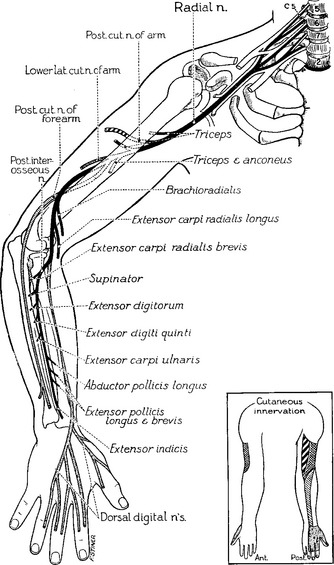

The radial nerve is the largest nerve in the upper extremity (Figure C12-2). It is a direct extension of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, after takeoff of the axillary nerve, and contains fibers from all the contributing roots of the plexus (i.e., C5 through T1).

Figure C12-2 Anatomy of the radial nerve and its branches.

(From Haymaker W, Woodhall B. Peripheral nerve injuries: principles of diagnosis. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1953, with permission.)

Clinical Features

Radial nerve lesions are usually acute and located around the spiral groove. Table C12-1 lists the common causes of radial nerve lesions in the arm. Among them, acute compression at the spiral groove, where the nerve comes in close contact with the humerus, is by far the most common. The radial nerve is compressed most often in the spiral groove after piercing the lateral intermuscular ligament, where the nerve lies unprotected by the triceps, against the humerus.

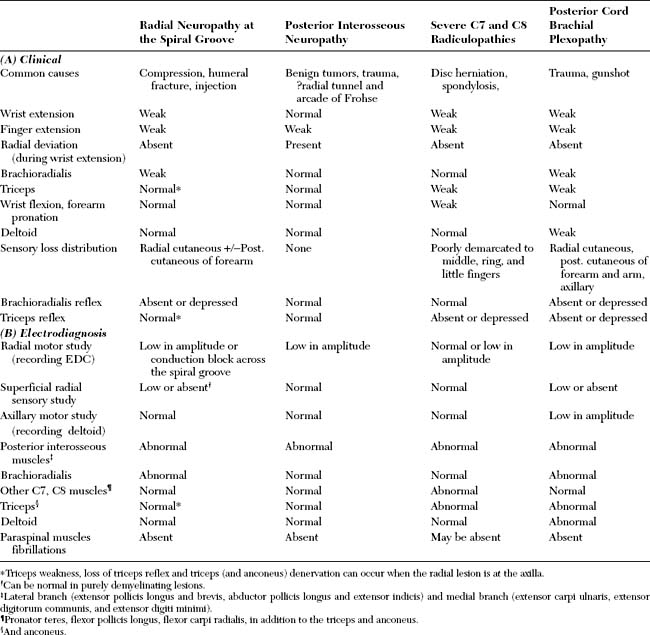

Radial nerve lesions, which often present with wrist- and finger-drop, should be distinguished from lesions of the posterior interosseus nerve and of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, and from severe cervical radiculopathies (C7 and C8 radiculopathies). Table C12-2(A) lists the clinical findings inpatients presenting with prominent wrist and/or finger extensor weakness.

Electrodiagnosis

Acute radial nerve lesions at the spiral groove are similar to acute common peroneal nerve lesions at the fibular head (see Case 8). Both are frequently caused by compression of the nerve between an external object and an internal rigid structure, such as the humerus or fibula. Also, their EDX findings are similar, with signs of axonal loss, conduction block due to segmental demyelination, or both. Except for open trauma (such as a gunshot or knife wound), which often results in axon loss lesions, one cannot predict the prognosis of radial nerve lesions, without EDX studies and quantitation of the extent of demyelination and axonal loss.

The needle EMG examination is essential in axon-loss lesions that are not localizable by NCS and confirmatory in lesions associated with conduction block (due to segmental demyelination or early axonal loss). The branches of the radial nerve are fortunately placed strategically in the arm and forearm, spanning the nerve length in its entirety. This renders the radial nerve one of the most convenient nerves to study in the EMG laboratory. Thus, even when the pathologic process is axonal, it frequently is possible to localize the lesion to a short segment of the nerve. This contrasts with many other human peripheral nerves, wherein the nerve travels in long segments without giving off any sensory or motor branches developing. Examples include the median and ulnar nerves, which have no branches in the arm, and the common peroneal nerve, which has a single motor branch in the proximal thigh (to the short head of the biceps femoris).

The first step in the diagnosis of a radial nerve lesion is to establish that the lesion involves the main trunk of the radial nerve; this is done by excluding restricted lesions of the posterior interosseus nerve, the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, and the C7 and C8 roots (Table C12-2(B)). A radial nerve lesion at the spiral groove, studied after the potential time to complete wallerian degeneration, is characterized by the following:

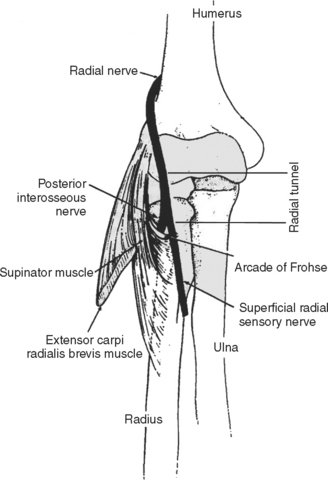

Radial Tunnel Syndrome

Despite its popularity among orthopedic and hand surgeons, there are many opponents to the existence of this syndrome. These physicians argue that (1) the symptoms of the RTS are seldom substantiated by clinical or electrophysiologic findings, (2) the tender points correlate with the “trigger points” described in regional myofascial pain syndromes, (3) the pain relief from corticosteroid injection is not a proof that the radial nerve is compressed, since patients with local musculoskeletal complaints, such as lateral epicondylitis or trigger points often get pain relief by blocks, and (4) cases of true compression of the posterior interosseous nerve are often due to mass lesions (e.g., ganglion), trauma, and, occasionally, entrapment at the arcade of Frohse and have definite neurological and EDX abnormalities that are consistent with axon-loss (Table C12-3). Many opponents believe that most patients with this alleged syndrome have actually a lateral epicondylitis (“tennis elbow”) that is resistant to treatment or have a regional myofascial syndrome rather than true nerve compression.

Table C12-3 Differences Between a “True” Posterior Interosseous Neuropathy and a “Presumed” Posterior Interosseous Nerve Entrapment in Radial Tunnel Syndrome

| Posterior Interosseous Neuropathy | Radial Tunnel Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathophysiology | Nerve compression, usually by mass (e.g., ganglion), acute trauma, and, rarely, by the tendinous arch at the arcade of Frohse | Presumed nerve entrapment at the radial tunnel, mostly, by the tendinous arch at the arcade of Frohse |

| Clinical manifestations | Objective and subjective weakness of PIN muscles*; rarely painful | Pain is always present with finger extension or supination; often with tenderness on palpation over the proximal lateral forearm with distal and/or proximal radiation; rarely weakness |

| Electrodiagnostic findings | Denervation in PIN muscles*; radial motor CMAP may be low; radial SNAP is normal | Usually normal |

FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s wristdrop and hypesthesia began to improve within 2 weeks. Three months after the accident, he had minimal weakness limited to the long finger extensors (4-/5) and a small patch of hypesthesia over the dorsum of the hand.

Barnum M, Mastey RD, Weiss A-PC, et al. Radial tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12:679-689.

Brown WF, Watson BV. Quantitation of axon loss and conduction block in acute radial palsies. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:768-773.

Cornblath DR, et al. Conduction block in clinical practice. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:869-871.

Cravens G, Kline DG. Posterior interosseous nerve palsies. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:397-402.

Fowler CJ, Danta G, Gilliatt RW. Recovery of nerve conduction after a pneumatic tourniquet: observation on the hind-limb of the baboon. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1972;35:638-647.

Kaplan PE. Posterior interosseous neuropathies: natural history. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:399-400.

Roles NC, Maudsley RH. Radial tunnel syndrome. Resistant tennis elbow as a nerve entrapment. J Bone J Surg. 1972;54B:499-508.

Rosenbaum R. Disputed radial tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:960-967.

Streib E. Upper arm radial nerve palsy after muscular effort: report of three cases. Neurology. 1992;42:1632-1634.