Case 11

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

An electromyography (EMG) examination was then performed.

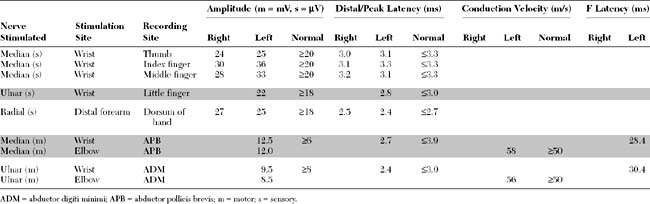

Please now review the Nerve Conduction Studies and Needle EMG tables.

QUESTIONS

EDX FINDINGS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA

Pertinent electrodiagnostic (EDX) findings in this case include:

DISCUSSION

Applied Anatomy

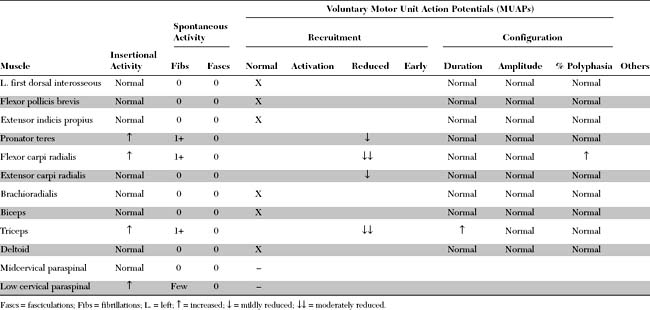

The dorsal root axons originate from the sensory neurons of the DRG, which lie outside the spinal canal, within the intervertebral foramen, immediately before the junction of the dorsal and ventral roots (Figure C11-1). These sensory neurons are unique because they are unipolar. They have proximal projections through the dorsal root, called the preganglionic sensory fibers, to the dorsal horn and column of the spinal cord. The distal projections of these neurons, called the postganglionic peripheral sensory fibers, pass through the spinal nerve to their respective sensory end-organs. The ventral root axons, however, are mainly motor (some are sympathetic, with origins from the anterolateral horn of the cord). The motor axons originate from the anterior horn cells within the spinal cord. Passing through the spinal nerves and the peripheral nerve, these motor fibers terminate in the corresponding muscles.

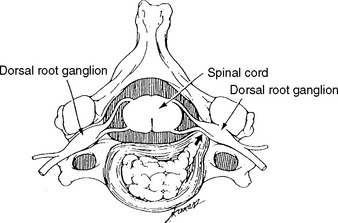

In humans, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerve roots: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal. In the cervical spine, each cervical root exits above the corresponding vertebra that shares the same numeric designation (Figure C11-2). For example, the C5 root exits above the C5 vertebra (i.e., between the C4 and C5 vertebrae). Because there are seven cervical vertebrae but eight cervical roots, the C8 root exits between the C7 and T1 vertebrae; subsequently, all thoracic, lumbar, and sacral roots exit below their corresponding vertebrae. For example, the L3 root exits below the L3 vertebra (i.e., between the L3 and L4 vertebrae).

Clinical Features

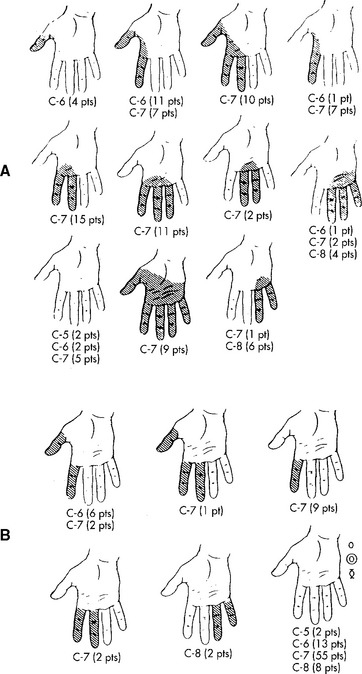

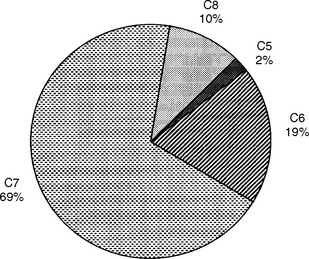

The classic study by Yoss et al., published in 1957, remains the best available clinicoanatomic study of cervical root compression. This detailed study analyzed the symptoms and signs of 100 patients with surgically proven single cervical lesions. C7 radiculopathy was the most common cervical radiculopathy, accounting for almost two thirds of patients (Figure C11-3). Figure C11-4 shows the common sensory symptoms and signs observed in these patients, while Figure C11-5 shows the weakened muscles caused by cervical radiculopathy. This study revealed the extreme variability of sensory manifestations in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Also, no single muscle was exclusively diagnostic of a specific root compression. However, based on the data, certain clinical conclusions can be made:

Figure C11-3 Incidence of cervical root involvement in a series of 100 patients with surgically proven single-level lesions.

(Data adapted from Yoss RE et al. Significance of symptoms and signs in localization of involved root in cervical disc protrusion. Neurology 1957;7:673–683, with permission.)

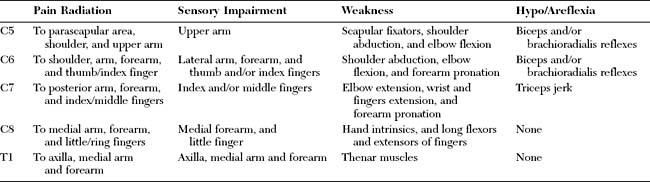

Figure C11-5 Incidence and severity of weakness of muscles or groups of muscles in cervical radiculopathy (C5–C8).

(From Yoss RE et al. Significance of symptoms and signs in localization of involved root in cervical disc protrusion. Neurology 1957;7:673–683, with permission.)

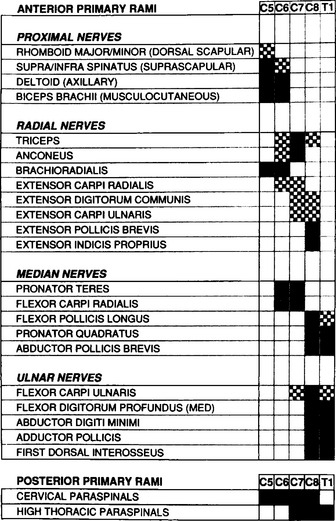

However, despite the variability in sensory and motor presentations of cervical radiculopathies, certain classical symptoms and signs exist and are extremely helpful in localizing the compressed root. Table C11-1 reveals the common presentations of cervical radiculopathies.

Electrodiagnosis

General Concepts

Goals of the Electrodiagnostic Study

Exclude a More Distal Nerve Lesion

Confirm Evidence of Root Compression

Two criteria are necessary to establish the diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy.

Table C11-2 Upper Extremity Sensory Nerve Action Potentials (SNAPs) and Their Segmental Representation

| Root | SNAP |

|---|---|

| C6 | Lateral antebrachial (Lateral cutaneous of forearm) |

| Median recording thumb | |

| Median recording index | |

| Radial recording dorsum of hand | |

| C7 | Median recording index |

| Median recording middle finger | |

| Radial recording dorsum of hand | |

| C8 | Ulnar recording little finger |

| Medial antebrachial (Medial cutaneous of forearm) | |

| T1 | Medial brachial (Medial cutaneous of arm) |

Localize the Compression to One or Multiple Roots

This requires meticulous knowledge of the segmental innervation of both limb muscles (myotomes) and skin (dermatomes). Many myotomal charts have been devised, with significant variability; this may lead to confusion and disagreement between the needle EMG and the level of root compression as seen by imaging techniques or during surgery. EMG-derived charts are also helpful and have had anatomic confirmation (see Levin et al. and Katirji et al.). Figure C11-6 reveals a common and most useful EMG-extracted myotomal chart.

A minimal “root search” should be performed in all patients with suspected cervical radiculopathy to ensure that a radiculopathy is either confirmed or excluded. In other words, certain muscles of strategic value in EMG because of their segmental innervation should be sampled (Table C11-3). When abnormalities are found or when the clinical manifestations suggest a specific root compression, more muscles must be sampled after being selected based on their innervation (see Figure C11-6), to verify the diagnosis and establish the exact compressed root(s).

Table C11-3 Suggested Muscles to be Sampled in Patients With Suspected Cervical Radiculopathy*

| First dorsal interosseous | C8, T1 |

| Flexor pollicis longus | C8, T1 |

| Pronator teres | C6, C7 |

| Biceps | C5, C6 |

| Triceps | C6, C7, C8 |

| Deltoid | C5, C6 |

| Mid-cervical paraspinal | C5, C6 |

| Low-cervical paraspinal | C7, C8 |

* Roots in bold type represent the major innervation.

Once myotomal denervation is detected by needle EMG, it is essential to confirm that the lesion is preganglionic (i.e., within the spinal canal) and not postganglionic (i.e., due to a brachial plexus injury). This can be achieved by recording one or more SNAPs appropriate for the myotome involved, and then establishing normality of SNAPs. For example, in a suspected C6 radiculopathy, the antidromic (or orthodromic) median SNAPs, recording the thumb and index, should be performed, preferably bilaterally for comparison (see Table C11-2).

Define the Age and Activity of the Radiculopathy

Define the Severity of the Radiculopathy

The best indicator of motor axon loss is the CMAP amplitude (or area) recorded during routine motor nerve conduction studies of the upper extremity. Although these studies are performed distally and do not include the roots, a root lesion causing demyelinative conduction block (or focal slowing), with little or no accompanying axonal degeneration, may result in weakness, but does not lead to any decrease in CMAP amplitude or other abnormalities on motor conduction studies. Only when significant axonal loss occurs at the root level does the CMAP recording from an involved muscle become low in amplitude (or occasionally absent when multiple adjacent roots are compressed). In acute lesions, this is only detected when sufficient time has elapsed for wallerian degeneration to occur (usually 7–10 days). For example, only in moderate or severe C8 radiculopathy is the ulnar CMAP, recording from abductor digiti minimi (C8, T1), borderline or low in amplitude at least after 10 days from onset of acute symptoms.

Electrodiagnostic Findings in Cervical Radiculopathies

C5/C6 Radiculopathies

C8/T1 Radiculopathies

As in the C5 and C6 situation, distinguishing C8 from T1 lesions is difficult because of significant myotomal overlap. The myotomal representation of the C8/T1 root involves the three major nerves in the upper extremity: the median, radial, and ulnar nerves. Muscles affected include the first dorsal interosseous and abductor digiti minimi (ulnar), the abductor pollicis brevis and flexor pollicis longus (median), and the extensor indicis proprius and extensor pollicis brevis (radial). The triceps muscle seldom is affected, but when also denervated, it is strong evidence of a C8 radiculopathy.

Could an EMG be Normal in a Patient With Definite Cervical Radiculopathy?

FOLLOW-UP

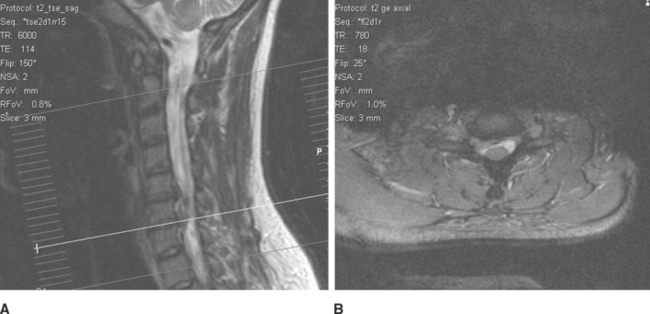

Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showed a large focal posterolateral disc herniation at the C6–C7 interspace, with impingement of the left C7 root and slight flattening of the cervical cord (Figure C11-7). The patient underwent an anterior cervical diskectomy at C6–C7. Intraoperatively, a large subligamentous disc herniation was observed to be compressing the left C7 root. Arm and neck pain began resolving in a few days and disappeared within 2 months. Strength improved steadily and, on reexamination 6 months later, the patient demonstrated normal triceps strength and reflex.

Benecke R, Conrad B. The distal sensory nerve action potential as a diagnostic tool for the differentiation of lesions in dorsal roots and peripheral nerves. J Neurol. 1980;223:231-239.

Bonney G, Gilliatt RW. Sensory nerve conduction after traction lesion of the brachial plexus. Proc R Soc Med (Clin Sec). 1958;51:365-367.

Katirji MB, Agrawal R, Kantra TA. The human cervical myotomes: an anatomical correlation between electromyography and CT/myelography. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:1070-1073.

Levin K. Cervical radiculopathies. In: Katirji B, Kaminski HJ, Preston DC, Ruff RL, Shapiro EB, editors. Neuromuscular disorders in clinical practice. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002:838-858.

Levin K, Maggiano HJ, Wilbourn AJ. Cervical radiculopathies: comparison of surgical and EMG localization of single-root lesions. Neurology. 1996;46:1022-1025.

Wilbourn AJ, Aminoff MJ. The electrophysiologic examination in patients with radiculopathies. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11:1099-1114.

Yoss RE, et al. Significance of symptoms and signs in localization of involved root in cervical disc protrusion. Neurology. 1957;7:673-683.