Chapter 10 Cartilage Tympanoplasty

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The use of cartilage in middle ear surgery is not a new concept; it has been recommended on a limited basis to manage retraction pockets for many years.1–5 More recently, the use of cartilage has been increasingly described for the reconstruction of large portions of the pars tensa of the tympanic membrane in cases of recurrent perforation, atelectasis, and cholesteatoma.6–8 Although one might anticipate a significant conductive hearing loss with cartilage because of its thickness and rigidity, several studies have reported results to the contrary, suggesting hearing results with cartilage to be no different than results with fascia.6–8 It has been shown in experimental and clinical studies that cartilage is well tolerated by the middle ear, and long-term survival is the norm.9–12 Cartilage grafts seem to be nourished largely by diffusion and become well incorporated in the tympanic membrane.3 Human and animal studies have shown that although some softening occurs with time, the matrix of the cartilage remains intact, but with development of empty lacunae, showing degeneration of the chondrocytes.13,14 The cartilage graft retains its rigid quality and resists resorption and retraction, even in the milieu of continuous eustachian tube dysfunction.

PATIENT SELECTION

Generally, cartilage is used as a graft material in any ear considered to be at high risk for failure with traditional techniques using temporalis fascia or perichondrium. Included in this group would be high-risk perforations, atelectatic ears, and cases of cholesteatoma. High-risk perforation comprises a revision surgery, a perforation anterior to the annulus, a perforation draining at the time of surgery, a perforation larger than 50%, or a bilateral perforation, all of which have been shown to be associated with increased failure rates using traditional techniques.15,16 The atelectatic ear is one of the most important indications for cartilage tympanoplasty, and numerous reports have established its efficacy over fascia in this situation.1–3 For similar reasons, the use of cartilage to reconstruct and reinforce the scutum and posterior half of the eardrum in cholesteatoma surgery has reduced the incidence of recurrent atrophy and retraction pockets in these difficult cases.

Cartilage tympanoplasty has proven to be efficacious in pediatric and adult patients, with special precautions used in the former group. The general approach to pediatric patients is to avoid repairing the tympanic membrane during the otitis-prone years (<3 years old). If the contralateral ear is normal, routine tympanoplasty is performed at age 4.17 If the contralateral ear is abnormal at this time, adenoidectomy is considered, and tympanoplasty is generally deferred until age 7.18,19 If contralateral disease is still present at this time, cartilage tympanoplasty is performed on the worse ear because a perforation in the contralateral ear has been shown to be associated with a high risk for failure.20

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Perichondrium/Cartilage Island Flap

The general technique of reconstruction using the perichondrium/cartilage island flap begins with harvest of the cartilage from the tragal area (see Video Clip 10-1).21 This cartilage is ideal because it is thin, flat, and in sufficient quantities to permit reconstruction of the entire tympanic membrane. The cartilage is used as a full-thickness graft and is typically slightly less than 1 mm thick in most cases. Although it has been suggested that a slight acoustic benefit could be obtained by thinning the cartilage to 0.5 mm,22 this advantage is offset by the unacceptable curling of the graft, which occurs when the cartilage is thinned, and perichondrium is left attached to one side.

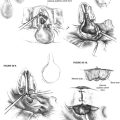

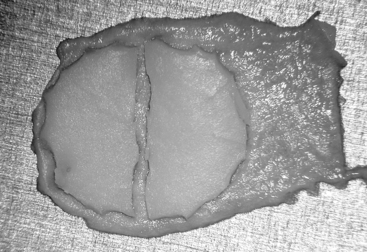

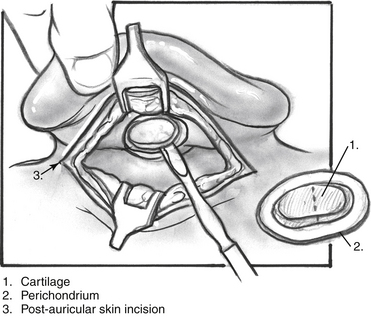

An initial cut through skin and cartilage is made on the medial side of the tragus, leaving a 2 mm strip of cartilage in the dome of the tragus for cosmesis (Fig. 10-1). The cartilage, with attached perichondrium, is dissected medially from the overlying skin and soft tissue by spreading a pair of sharp scissors in a plane that is easily developed superficial to the perichondrium on both sides. It is necessary to make an inferior cut as low as possible to maximize the length of harvested cartilage. The cartilage is grasped and retracted inferiorly, which delivers the superior portion from the incisura area. The superior portion is dissected out while retracting, which produces a piece of cartilage typically measuring 15 × 10 mm in children and larger in adults.

FIGURE 10-1 Harvest of cartilage, leaving small rim of cartilage in dome for cosmesis (right ear).

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

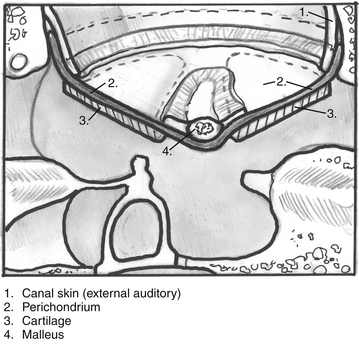

The perichondrium from the side of the cartilage farthest from the ear canal is dissected off, leaving the thinner perichondrium on the reverse side. A perichondrium/cartilage island flap is constructed in the following manner. Using a round knife, cartilage is dissected from the graft to produce an eccentrically located disc, approximately 7 to 9 mm in diameter, which is used for total tympanic membrane reconstruction. A flap of perichondrium is produced posteriorly that eventually drapes over the posterior canal wall. A complete strip of cartilage 2 mm wide is removed vertically from the center of the graft to accommodate the entire malleus handle (Fig. 10-2). The creation of two cartilage islands in this manner is essential to enable the reconstructed tympanic membrane to bend and conform to the normal conical shape of the tympanic membrane. When the ossicular chain is intact, an additional triangular piece of cartilage is removed from the posterosuperior quadrant to accommodate the incus. This excision prevents the lateral displacement of the posterior portion of the cartilage graft that sometimes occurs because of insufficient space between the malleus and incus.

FIGURE 10-2 Prepared perichondrium/cartilage island graft, showing strip of cartilage removed to facilitate malleus.

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

The entire graft is placed in an underlay fashion, with the malleus fitting in the groove and pressing down into and conforming to the perichondrium (Fig. 10-3). The cartilage is placed toward the promontory, with the perichondrium immediately adjacent to the tympanic membrane remnant, both of which are medial to the malleus. Failure to remove enough cartilage from the center strip causes the graft to fold up at the center instead of lying flat in the desired position. Likewise, if the strip is insufficient, the cartilage may be displaced medially instead of assuming a more lateral position in the same plane as the malleus.

FIGURE 10-3 Lateral line drawing showing proper placement of graft.

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

Absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) is packed in the middle ear space underneath the anterior annulus to support the graft in this area, and the posterior flap of perichondrium is draped over the posterior canal wall. Middle ear packing is avoided on the promontory and in the vicinity of the ossicular chain. One piece of Gelfoam is placed lateral to the reconstructed tympanic membrane, and antibiotic ointment is placed in the ear canal (Fig. 10-4).

Palisade Technique

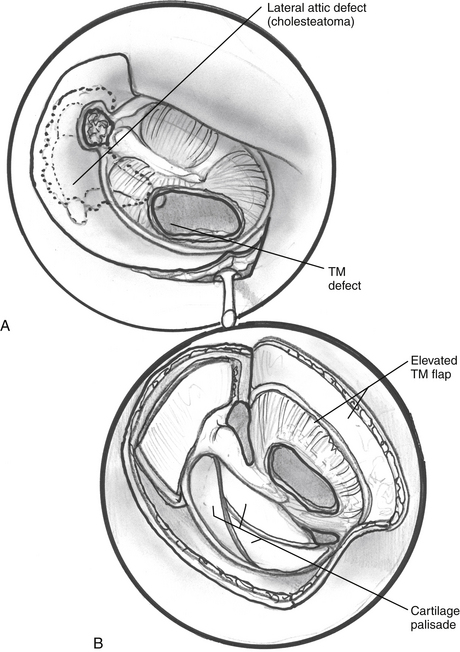

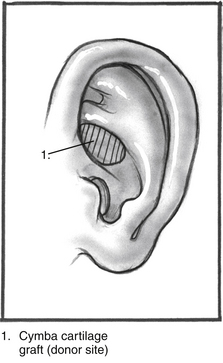

The cartilage is cut into several slices that are subsequently pieced together, similar to a jigsaw puzzle, to reconstruct the tympanic membrane (Figs. 10-5 and 10-6). A large area of conchal eminence can be exposed by elevating the subcutaneous tissue and postauricular muscle from the conchal perichondrium. The cymba cartilage is the prominent bulge at the superior aspect of the concha (Fig. 10-7). A circumferential cut the size of the anticipated graft is made through the perichondrium and cartilage, but not through the anterior skin. The perichondrium is removed from the postauricular side, and the cartilage, with the perichondrium on the anterior aspect, is dissected from the skin. This technique is also used for harvesting cartilage for canal wall reconstruction when the retrograde mastoidectomy technique is used for cholesteatoma surgery.

FIGURE 10-5 A and B, Schematic of palisade technique (right ear). TM, tympanic membrane.

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

FIGURE 10-6 Schematic illustrating location of cymba cartilage (left ear).

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

FIGURE 10-7 Harvesting of cymba cartilage with postauricular incision (right ear).

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

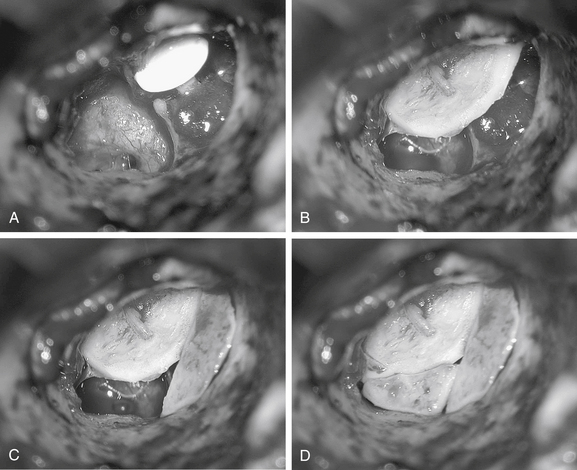

The technique described here differs from the palisade tympanoplasty of Heermann and colleagues.23 Instead of placing rectangular strips of cartilage side to side, an attempt is made to cut one major piece of cartilage in a semilunar fashion, which is placed directly against the malleus on top of the prosthesis (Fig. 10-8A and B). This piece of cartilage acts to reconstruct a major portion of the posterior half of the tympanic membrane, and serves as a foundation for the rest of the cartilage pieces. A second semilunar piece is placed between this first piece and the canal wall to reconstruct the scutum precisely (Fig. 10-8C). Any spaces that result between this cartilage and the canal wall or scutum are filled in with small slivers of cartilage to prevent prosthesis extrusion and recurrent retraction (Fig. 10-8D). The reconstruction is covered with the previously harvested perichondrium draped over the posterior canal wall (Fig. 10-9).

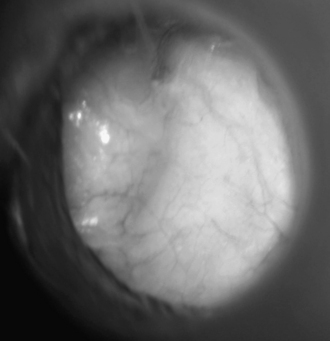

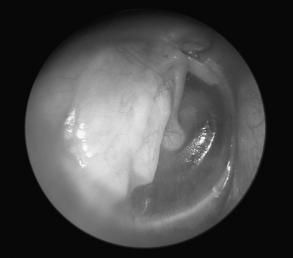

FIGURE 10-9 Postoperative appearance of tympanic membrane after palisade reconstruction (right ear).

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

Although this technique can be used for tympanic membrane reconstruction without ossicular reconstruction, it is favored when ossiculoplasty is performed in a situation with the malleus present, and is especially suitable for cholesteatoma surgery. Because the prosthesis is placed before the cartilage reconstruction, the palisade technique allows direct visualization and contact of the notched prosthesis to the manubrium handle, which has been shown to provide superior hearing results.24 The prosthesis acts as a scaffolding on which the cartilage is placed, which serves to reconstruct the tympanic membrane and prevent prosthesis extrusion. It likewise allows a precise and watertight fit between the reconstructed tympanic membrane and the canal wall in the posterior area, where recurrent cholesteatoma most frequently occurs. Typically, in these situations, the anterior half of the tympanic membrane is not altered or is grafted with conventional materials to allow cholesteatoma surveillance and possible intubation in the postoperative period if necessary.

PROBLEMS AND PITFALLS

Postoperative Complications

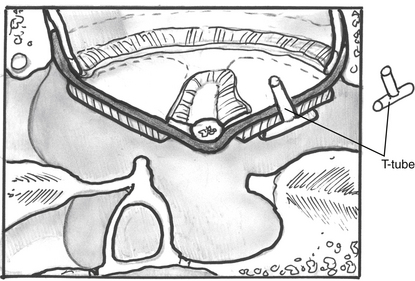

In cases of more pervasive eustachian tube dysfunction, such as in patients with craniofacial abnormalities (including Down syndrome), previous head and neck cancer involving the nasopharynx, or a history of multiple ear surgeries, a T-tube is inserted in the cartilage graft during the initial surgery. The perichondrium/cartilage island graft is harvested and prepared as previously described. Using a round knife, a window that is large enough to allow placement of a Xomed Modified Goode T-tube (Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville, FL) is cut into the anterior cartilage island. A straight pick is placed into the cartilage window to dilate the perichondrium to allow tube placement. Before insetting the graft, the tube is placed into the cartilage window and brought out through the perichondrial surface. If the malleus is present, the end of the tube is first angled under the manubrium with small alligator forceps. After hooking the tube under the malleus, the graft is slid forward into place. If the malleus is absent, the graft/tube complex is slid directly into its final position (Fig. 10-10).

FIGURE 10-10 Technique of cartilage tympanoplasty with intraoperative placement of T-tube.

(From Dornhoffer JL: Cartilage tympanoplasty: Indications, techniques, and outcomes in a 1000-patient series. Laryngoscope 113:1844-1856, 2003.)

Another problem that may occur postoperatively concerns a patient with reconstruction after cholesteatoma removal. One serious disadvantage of using cartilage for reconstruction in cholesteatoma surgery is that it creates an opaque tympanic membrane posteriorly, which could potentially hide residual disease. This is a problem that should be recognized, and surgical discretion should be used. If major disruption of the cholesteatoma sac occurs at extirpation, one must consider the advisability of performing a second-look surgery at a later date. This consideration applies to cholesteatoma surgery in general, not only in cases where cartilage is used in the reconstruction. One must also recognize the fact that most residual disease occurs in the epitympanum, an area that is hidden by the bony canal wall and scutum when canal wall-up surgery of any type is performed.25 Although posterior cartilage tympanic membrane reconstruction can delay the diagnosis of residual cholesteatoma, the disease becomes manifest either anteriorly or as a recurrence of a conductive hearing loss, and there should be no major complications because of this delay in diagnosis.26,27

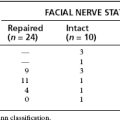

RESULTS

Because of the good anatomic results, attention has more recently been given to the acoustic properties of cartilage compared with more traditional grafting materials. In a retrospective comparison between perichondrium and cartilage in type I tympanoplasties, we reported no significant difference in hearing between groups.28 Our larger series of more than 1000 cases continued to show encouraging results, which have been supported by other authors who have shown excellent closure of the air-bone gap with cartilage tympanoplasty techniques.14,19,20,29 Because of the postoperative appearance of the tympanic membrane after cartilage tympanoplasty, it is surprising that no hearing loss is incurred. There is no satisfactory explanation for this phenomenon, other than that the dictum of “form follows function” seems not to apply to cartilage tympanoplasty.

1. Sheehy J.L. Surgery of chronic otitis media. In: English G., editor. Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Harper & Row; 1985:1-86.

2. Glasscock M.E.III, Hart M.J. Surgical treatment of the atelectatic ear. In: Friedman M., editor. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1992:15-20.

3. Levinson R.M. Cartilage-perichondrial composite graft tympanoplasty in the treatment of posterior marginal and attic retraction pockets. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:1069-1074.

4. Eviatar A. Tragal perichondrium and cartilage in reconstructive ear surgery. Laryngoscope. 1978;88(Suppl 11):11-23.

5. Adkins W.Y. Composite autograft for tympanoplasty and tympanomastoid surgery. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:244-247.

6. Milewski C. Composite graft tympanoplasty in the treatment of ears with advanced middle ear pathology. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1352-1356.

7. Amedee R.G., Mann W.J., Riechelmann H. Cartilage palisade tympanoplasty. Am J Otol. 1989;10:447-450.

8. Duckert L.G., Muller J., Makielski K.H., Helms J. Composite autograft “shield” reconstruction of remnant tympanic membranes. Am J Otol. 1995;16:21-26.

9. Loeb L. Autotransplantation and homotransplantation of cartilage in the guinea pig. Am J Pathol. 1926;2:111-122.

10. Peer L.A. The fate of living and dead cartilage transplanted in humans. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1939;68:603-610.

11. Kerr A.G., Byrne J.E., Smyth G.D. Cartilage homografts in the middle ear: A long-term histological study. J Laryngol Otol. 1973;87:1193-1199.

12. Don A., Linthicum F.H.Jr. The fate of cartilage grafts for ossicular reconstruction in tympanoplasty. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1975;84:187-191.

13. Yamamoto E., Iwanaga M., Fukumoto M. Histologic study of homograft cartilages implanted in the middle ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;98:546-551.

14. Hamed M., Samir M., El Bigermy M. Fate of cartilage material used in middle ear surgery light and electron microscopy study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1999;26:257-262.

15. Black B. Ossiculoplasty prognosis: The spite method of assessment. Am J Otol. 1992;13:544-551.

16. Goldenberg R.A. Hydroxylapatite ossicular replacement prostheses: Preliminary results. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:693-700.

17. Buchwach K.A., Birck H.G. Serous otitis media and type 1 tympanoplasties in children: A retrospective study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1980;89:324-325.

18. Strong M.S. The eustachian tube: Basic considerations. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1972;5:19-27.

19. Bailey H.A.Jr. Symposium: Contraindications to tympanoplasty, I: Absolute and relative contraindications. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:67-69.

20. Raine C.H., Singh S.D. Tympanoplasty in children: A review of 114 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:217-221.

21. Dornhoffer J.L. Hearing results with cartilage tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1094-1099.

22. Zahnert T., Huttenbrink K.B., Murbe D., Bornitz M. Experimental investigations of the use of cartilage in tympanic membrane reconstruction. Am J Otol. 2000;21:322-328.

23. Heermann J.Jr., Heermann H., Kopstein E. Fascia and cartilage palisade tympanoplasty: Nine years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91:228-241.

24. Dornhoffer J.L., Gardner E. Prognostic factors in ossiculoplasty: A statistical staging system. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:299-304.

25. Smyth G.D. Cholesteatoma surgery: The influence of the canal wall. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:92-96.

26. Parisier S., Hanson M. Pediatric cholesteatoma: Results of individualized single surgery management. In: Sanna M., editor. Fifth International Conference on Cholesteatoma and Mastoid Surgery. Alghero-Sardinia, Italy, CIC: Edizioni Internazionali; 1997:375-385.

27. Hirsch B.E., Kamerer D.B., Doshi S. Single-stage management of cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;106:351-354.

28. Dornhoffer J.L. Hearing results with the Dornhoffer ossicular replacement prostheses. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:531-536.

29. Dornhoffer J.L. Surgical modification of the difficult mastoid cavity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:361-367.