Chapter 26 Carotid artery stenting

The time has now come to regard carotid artery stenting (CAS) as a realistic alternative to Carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Based on the availability of safe techniques, on trial evidence and the presence of a cohort of over 12 000 patients that have been treated successfully worldwide.

The time has now come to regard carotid artery stenting (CAS) as a realistic alternative to Carotid endarterectomy (CEA). Based on the availability of safe techniques, on trial evidence and the presence of a cohort of over 12 000 patients that have been treated successfully worldwide. Three major patient groups need to be considered for carotid intervention: symptomatic, asymptomatic and pre-cardiac surgery.

Three major patient groups need to be considered for carotid intervention: symptomatic, asymptomatic and pre-cardiac surgery.INTRODUCTION

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the developed world.1 Internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis is a major cause of ischaemic stroke, with the risk being related to the degree of stenosis and the presence of recent symptoms.2,3 Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) has become the preferred method of treatment for patients with asymptomatic or symptomatic high grade ICA stenosis, supplanting medical therapy alone. The time has now come to regard carotid artery stenting (CAS) as a realistic alternative to CEA. This statement is based on the availability of safe techniques, on trial evidence and the presence of a cohort of over 12 000 patients that have been treated successfully worldwide.4

HISTORY

Atherosclerosis of the carotid bifurcation was suggested as a risk factor for stroke over 50 years ago.5 Surgery of this area was developed at a similar time by Eastcott in the UK, and Debakey in the US.6,7 Following this, CEA became a popular procedure amongst vascular surgeons. In the USA alone, more than 100 000 CEA procedures were performed in 1985, well before the publication of randomised controlled trial data.8 In the ensuing confusion about indications and outcomes, a number of trials began to clarify the correct role for CEA in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.9,10–12 CEA remains the most common vascular operation in the US.

The report of first carotid angioplasty was published in 1983, with stenting becoming popular in the early 1990s.13,14 By 1994, Roubin et al. were performing CAS on a routine basis in the USA.15 Distal protection devices (DPD) were developed in a primitive form in 1987.16 It has really been the development of more usable DPD that has lead to the rapid growth of CAS in recent years.4

PATIENT SELECTION

Three major patient groups need to be considered for carotid intervention:

Symptomatic

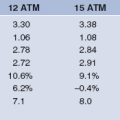

Three trials have addressed the issue of the treatment of symptomatic ICA stenosis. The VA trial was terminated early due to publication of the results of the other two.17 (Table 26.1).

TABLE 26.1 TRIAL EVIDENCE FOR THE USE OF CEA IN SYMPTOMATIC AND ASYMPTOMATIC ICA STENOSIS. ALL END POINTS ARE 30-DAY DEATH AND STROKE RATES. CVA=STROKE

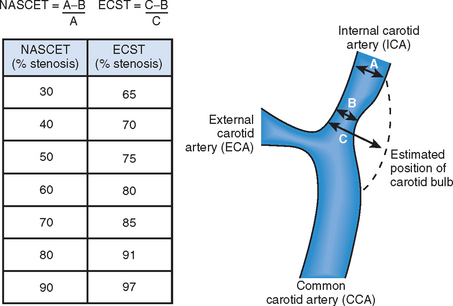

The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) randomised 2885 patients with 30–99% ICA stenoses at angiography and recent stroke (CVA) or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) to medical therapy or CEA. In patients with 70–99% stenosis, operation reduced two-year ipsilateral CVA risk from 26% to 9% (relative risk reduction 65%) and combined major CVA and death rates from 13.1% to 2.5% (relative risk reduction 81%).9 In those with 50–69% stenosis, five-year ipsilateral CVA risk was reduced from 22.2% to 15.7% (relative risk reduction 29%).18 There was no benefit in patients with stenosis <50%, although this group still had an event rate of 15–19% at two years, suggesting medical therapy also needed to be improved.

The European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) randomised 3024 patients with symptomatic ICA stenosis in a similar manner, using duplex ultrasound criteria of >60% stenosis.10,19 In patients with 70–99% stenosis, at three years, risk of ipsilateral CVA was reduced from 16.8% to 10.3% (relative risk reduction 39%). Risk of major stroke or death was reduced from 11% to 6% (relative risk reduction 45%). There was no benefit in patients with <70% duplex stenosis.

A meta-anaylsis of these and the VA trial suggested most benefit in men, those >75, and those treated within two weeks.20 So, for symptomatic patients, a duplex stenosis of >70–75% (angiographic >50%) should be treated to improve prognosis. American guidelines suggest that the surgeon should have <6% peri-procedural CVA and death rates for the procedure to be useful.21

Asymptomatic

The value of CEA in asymptomatic ICA stenosis is less clear. Three small initial trials failed to show a benefit, but may have been underpowered to do so.22–24 However, there are now two larger trials which have shown positive results12,25 (Table 26.1).

The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) studied 1662 patients under the age of 80 with >60% ultrasound stenosis, randomizing them to CEA or medical therapy.25 At five years, the risk of ipsilateral CVA or death was reduced from 11% to 5.1% by CEA. The value of the procedure in women was not proven.

The Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) randomized 3120 patients, and again used >60% stenosis on ultrasound as the entry criterion, and showed that after five years, ipsilateral CVA or death rate was reduced from 11.8% to 6.4% by CEA.12

So, in asymptomatic patients, a stenosis of >60% could be treated, if the patient is male, <80-years-old, and has a good chance of living for five years. Since the benefits was mainly in those with >75% stenosis, this is a more robust cut-off to use, matching an angiographic stenosis of 50% by NASCET criteria (Fig. 26.3).

It should be recalled that the background event rate is <2% stroke risk per year, which would be reduced to 1% by the procedure. This compares well with the risk reductions offered by lipid lowering therapy, or comparing the benefit of Clopidogrel over Aspirin in patients with vascular disease.26–27 American guidelines suggest that the surgeon should have a <3% peri-procedural CVA and death rate for asymptomatic patients for the procedure to be useful.21

Pre-cardiac surgery

Those patients with asymptomatic ICA stenoses facing CABG or valve surgery have elevated peri-operative CVA risk. Whether carotid intervention is beneficial in some or all is controversial, since CEA itself can carry a higher risk in the presence of severe cardiac disease.28 A review of the limited data suggests that the hemodynamic consequences may not be relevant with a unilateral stenosis, but if the numerical addition of the stenoses of the ICA on both sides is >140%, then intervention on the more severe side is acceptable.29 If brain imaging suggests an inadequate collateral supply to the hemisphere supplied by a tight carotid stenosis, then this unilateral stenosis may be worth treating. On the basis of the SAPPHIRE trial (see below), CAS would seem the more appropriate therapy in such cases.30

CAS versus CEA

Trials of CAS versus medical therapy are unlikely to be performed as CEA has been shown to be better than medical therapy in patients with significant ICA stenosis. Thus, on-going trials would need to confirm that CEA and CAS are equivalent if CAS is to become the mainstay of treatment for ICA stenosis. There are patients, however, who have been shown to be at elevated operative risk, and who might benefit from a percutaneous approach if risks were shown to be lower.28,31–33 (Table 26.2).

| CONDITION | DETAILS |

|---|---|

| High Medical | Age >80 |

| Co-morbidity | Coronary disease (CAD) with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) <4 weeks ago |

| Any severe CAD | |

| Congestive cardiac failure | |

| Dialysis dependant renal failure | |

| Chronic airways disease (FEV1 <1 L) | |

| Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus | |

| Local surgical factors | Restenosis after Endarterectomy (CEA) |

| Radiation induced Carotid stenosis | |

| Anatomically high ICA stenosis (above C2) | |

| Prior neck scarring or surgery | |

| Contralateral recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury | |

| Contralateral internal carotid artery occlusion |

CEA carries risks, including CVA, surgical haematoma, cranial nerve injury and risks related to anaesthesia.34 These risks in real life are higher than those reported in the trials, both due to patient and indeed operator selection, since the best and largest volume operators often participate in these studies.35 The same operator volume dependency has also been seen for CAS, with early cases having a higher complication rate than later ones, the so-called ‘learning curve’.36 Even in early experience of 528 cases of CAS from Roubin et al., however, the safety of CAS became clear. Despite 83% of the symptomatic patients being ineligible for CEA by NASCET criteria due to co-morbidity, 30-day CVA and death rates were 7.4%, comparable to those for CEA in the NASCET trial.

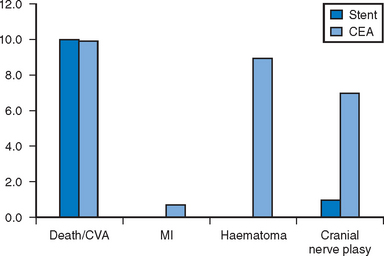

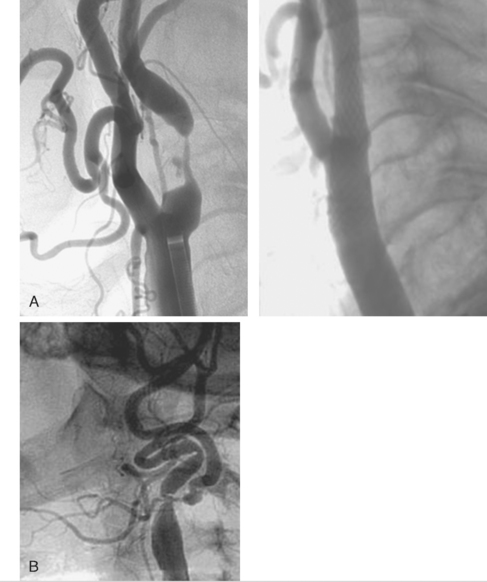

There are now two published randomised trials of CAS against CEA. The Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS) randomised 504 patients with symptomatic ICA stenosis to balloon angioplasty (only 26% got a stent) or CEA. This showed that 30-day stroke and death rates were equivalent in both arms at 9%, but that hematomas and cranial nerve injuries were higher in the CEA arm (Fig. 26.1). Although it was argued that the peri-operative risk was too high in the CEA arm, these were experienced surgeons who had participated in previous trials, and in fact it was CAS, which was still a novel procedure, without the use of DPDs, that should have been disadvantaged.37

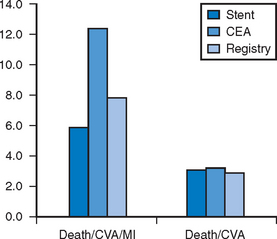

The Stenting and Angioplasty with Protection in Patients at High Risk for Endarterectomy (SAPPHIRE) study was the first trial to compare CEA with modern CAS utilising DPD.30 All patients were considered high risk (Table 26.2). A total of 723 patients were enrolled with stenoses of >50% if symptomatic or >80% if asymptomatic. Of these, 307 were randomised to CAS versus CEA. However, 409 were considered unsuitable for CEA and were put in the CAS registry, whilst only seven patients were considered unsuitable for CAS, and were placed in the CEA registry. All CAS procedures were done with the Angioguard DPD and Precise stent (Cordis, Johnson and Johnson). The outcome of 30-day stroke and death rate was 3.1% for CAS versus 3.3% for CEA (p=ns). More interestingly, the rate in the stent registry was also only 3% (Fig. 26.2). Myocardial infarction was defined as rise of creatinine kinase twice the upper limit of normal. The combined endpoint of the study (death/CVA/MI) occurred in 5.8% of the CAS group versus 12.6% of the CEA group (p=0.047). The same trend was seen in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, and was maintained at one year.

Thus, in higher risk patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic ICA stenosis, results of CAS are as good if not better than CEA. On this basis, CAS is a reasonable alternative strategy to be offered to such patients.

For lower risk patients, results of ongoing trials are awaited, but there appears no logical reason to assume CAS will not also be the treatment of choice in this larger cohort.38–40,41

Key investigations

Carotid duplex scanning

Due to ease of access, the carotid duplex ultrasound scan has become the screening tool of choice. There is considerable skill involved in performing and interpreting the scan. There is a correlation between stenosis assessed at angiography and duplex measurement (Fig. 26.3). Attempts have been made to try to improve plaque characterisation, and these may develop further with the advent of virtual histology. There is some data to suggest that plaque morphology predicts outcome after intervention, although the jury is still out.42,43

MRA

Access to magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is limited in the UK, but can produce excellent images of the aortic arch, great vessels, and intra-cerebral vasculature. Decisions on treatment may be swayed by the presence or absence of intracerebral collaterals from the circle of Willis. However, pseudo-stenoses can result from movement artefact.

TECHNIQUE FOR CAS

Planning and pre-treatment

Pre-operative medication

Use of adjunctive pharmacology has improved outcomes in PCI. Data in CAS suggests that use of DPDs gives greater benefit than use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa agents.44,45 There is a danger of haemorrhagic transformation if embolic CVA occurs with these agents on board. However, they may find a place in addition to DPDs to reduce platelet aggregation within the filter device. This needs to be tested in further trials.

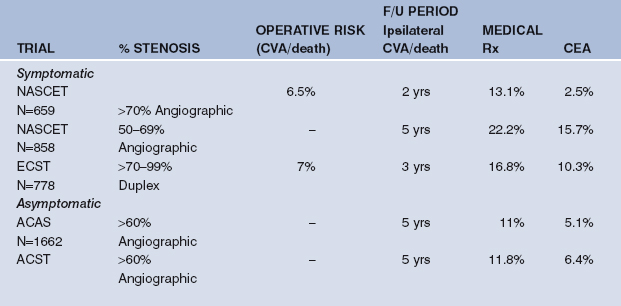

Gaining a stable working platform

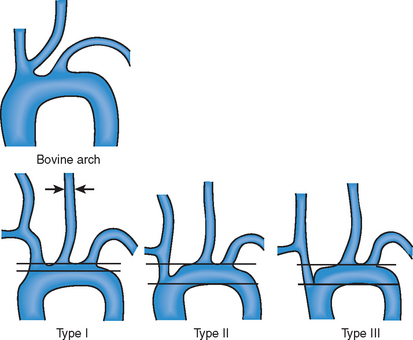

A standard technique should be employed to gain familiarity with the approach (Table 26.3). Various catheter shapes are available to try to intubate the common carotid artery selectively, including Vitek, Berenstein and Sidewinder. Problems arise with a bovine origin of the left CCA or deep-seated origins of the great arteries (Fig. 26.4). Most commonly the procedure used by radiologist involves a long sheath as the conduit, whilst cardiologists prefer a 7 F or 8 F guide catheter. Care needs to be taken not to perforate a branch of the ECA with the stiff wire used to support placement of the guide catheter. The ability to store a roadmap of the lesion allows easy passage of the angioplasty wire or DPD.

TABLE 26.3 SUMMARY OF TECHNIQUE TO PERFORM CAROTID ARTERY STENTING IN STANDARD CASES.

MODIFIED FROM HOBSON ET AL.55

Distal protection or not?

Micro-embolisation is thought to be the major cause of peri-operative neurological complications during CAS.46 Transcranial Doppler measurements suggest that without distal protection, the incidence of micro-embolisation is higher with CAS than CEA.47 Thus prevention of distal embolisation would seem logical. This can be achieved with distal filter devices, distal occlusion devices, or proximal occlusion devices (Table 26.4). Most cardiologists are likely to prefer distal protection filters due to familiarity. Large scale trials comparing outcomes with and without distal protection are lacking, but registry data suggests that some form of protection device should be used in most cases. Event rates (30-day stroke and death) in symptomatic patients having CAS in the pre-protection era were 6.7% versus 2.82% in the modern age (Wholey MH, ACC Scientific sessions presentation 2003). For asymptomatic patients, rates were 3.97% and 1.75% respectively.

TABLE 26.4 EMBOLIC PROTECTION DEVICES USED FOR CAROTID ARTERY STENT (CAS) PROCEDURES WITH ADVANTAGE AND DISADVANTAGES LISTED. INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY (ICA), EXTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY (ECA)

| TECHNIQUE | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Balloon occlusion |

The third device involves the proximal occlusion of the CCA and the external carotid artery (ECA). A large catheter with an extension arm for the ECA is advanced into the CCA. Occlusion balloons mounted on the catheter are inflated in the CCA and then the ECA. This creates a negative pressure in the ICA and should allow the collaterals in the circle of Willis to produce reverse flow, preventing distal embolisation into the ICA. The stent procedure is then performed and aspiration performed to clear debris from the ICA prior to device removal.

Complications and management

Perforation of ECA

If seen on angiography, then bleeding is occurring at a rate of at least 3 ml/minute.48 Continued bleeding may cause substantial sub-glottic swelling and may necessitate intubation to protect the airway. If conservative management fails, there may be a need to embolise the branch of the ECA that is bleeding with a coil, glue or foam.49

Vessel rupture

Although rare, high pressure balloon inflation in calcified lesions may cause ICA rupture. This is usually managed conservatively.50

Neurological

The most dreaded complications are neurological. No DPD is 100% efficient in catching debris, and in addition, there is an incidence of late embolic stroke after the DPD is removed, in the first seven days post-procedure. This is presumably generated by detachment of a mobile piece of atheroma.51 Late events are usually managed conservatively once bleeding has been excluded. Large CVAs occurring during the procedure should prompt intracerebral angiography to exclude acute occlusion due to embolism. The role of thrombolysis in this situation is not defined, and catheter and wire-based fragmentation of the debris may be warranted. Haemorrhagic stroke during the procedure will necessitate full reversal of anti-coagulants.

The hyperperfusion syndrome occurs in a small number of cases. Headache, fits or CVA may be the clinical manifestation. It is thought that increased cerebral perfusion after intervention (CEA and CAS) overwealms cerebral autoregulation. Intracerebral bleeding can be catastrophic. For this reason, bilateral procedures should be avoided and blood pressure control should be achieved prior to carotid intervention.52

The ideal training program

Consensus is slowly being reached on the ideal training program for becoming competent in CAS procedures.53 Worldwide, interventional cardiologists, interventional radiologists and vascular surgeons are performing the procedures. An ideal pathway would include all the following:

This may need a validated training program to ensure knowledge base is adequate.

This may be augmented by attending live-case meetings

Perhaps more important still is that adequate clinical governance and review procedures are in place to allow practice to be monitored, and problems to be resolved without patient risk. Training of the staff in the interventional lab and recovery areas is vital to reducing patient risk.

CONCLUSIONS

CEA is not as invasive as CABG surgery, whilst CAS carries higher risks than PCI since the brain is more unforgiving than the myocardium. However, as with the coronary field, the move towards the development of less invasive treatments is unrelenting and with the appropriate training, many interventionalists will be able to perform CAS safely. As with coronary intervention, case selection in the early phase of the ‘learning curve’ will allow the program to develop. The more difficult lesion can still be referred for CEA until sufficient catheter skills have developed (Fig. 26.5).

A review by NICE in the UK is awaited, but present guidelines on the management of stroke suggest that CAS is a rapidly evolving procedure and encourage those performing stenting to take part in the ICSS trial (http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=218167).

1 American Heart Association. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics, 2003 update. Dallas Scientitic Sessions, Texas, USA: American Heart Association, 2003.

2 Barnett HJ, Gunton RW, Eliasziw M, Fleming L, Sharpe B, Gates P, et al. Causes and severity of ischemic stroke in patients with internal carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 2000;283(11):1429-1436.

3 Inzitari D, Eliasziw M, Gates P, Sharpe BL, Chan RK, Meldrum HE, et al. The causes and risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic internal-carotid-artery stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(23):1693-1700.

4 Wholey MH, Al Mubarek N, Wholey MH. Updated review of the global carotid artery stent registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;60(2):259-266.

5 Fischer CM, Gore I, Okabe N, White PD. Atherosclerosis of the carotid and vertebral arteries: extracranial and intracranial. J Neuropath Exp Neurol. 1965;24:455-476.

6 Eastcott HH, Pickering GW, Rob CG. Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia. Lancet. 1954;267(6846):994-996.

7 DeBakey ME. Successful carotid endarterectomy for cerebrovascular insufficiency. Nineteen-year follow-up. JAMA. 1975;233(10):1083-1085.

8 Tu JV, Hannan EL, Anderson GM, Iron K, Wu K, Vranizan K, et al. The fall and rise of carotid endarterectomy in the United States and Canada. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1441-1447.

9 Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(7):445-453.

10 MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial: interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70–99%) or with mild (0–29%) carotid stenosis. European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1991;337(8752):1235-1243.

11 Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995;273(18):1421-1428.

12 Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9420):1491-1502.

13 Bockenheimer SA, Mathias K. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in arteriosclerotic internal carotid artery stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4(3):791-792.

14 Diethrich EB, Ndiaye M, Reid DB. Stenting in the carotid artery: initial experience in 110 patients. J Endovasc Surg. 1996;3(1):42-62.

15 Yadav JS, Roubin GS, Iyer S, Vitek J, King P, Jordan WD, et al. Elective stenting of the extracranial carotid arteries. circ. 1997;95(2):376-381.

16 Theron J, Raymond J, Casasco A, Courtheoux F. Percutaneous angioplasty of atherosclerotic and postsurgical stenosis of carotid arteries. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8(3):495-500.

17 Mayberg MR, Wilson SE, Yatsu F, Weiss DG, Messina L, Hershey LA, et al. Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 309 Trialist Group. JAMA. 1991;266(23):3289-3294.

18 Barnett HJ, taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1415-1425.

19 Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet. 1998;351(9113):1379-1387.

20 Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet. 2004;363(9413):915-924.

21 Goldstein LB, Adams R, Becker K, Furberg CD, Gorelick PB, Hademenos G, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. circ. 2001;103(1):163-182.

22 The CASANOVA Study Group. Carotid surgery versus medical therapy in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke. 1991;22(10):1229-1235.

23 Results of a randomized controlled trial of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Mayo Asymptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Study Group. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67(6):513-518.

24 Hobson RW, Weiss DG, Fields WS, Goldstone J, Moore WS, Towne JB, et al. Efficacy of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):221-227.

25 Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995;273(18):1421-1428.

26 A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee [see comments]. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1329-1339.

27 LIPID study group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with Pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

28 Borger MA, Fremes SE, Weisel RD, Cohen G, Rao V, Lindsay TF, et al. Coronary bypass and carotid endarterectomy: does a combined approach increase risk? A metaanalysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68(1):14-20.

29 Naylor R, Cuffe RL, Rothwell PM, Loftus IM, Bell PR. A systematic review of outcome following synchronous carotid endarterectomy and coronary artery bypass: influence of surgical and patient variables. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;26(3):230-241.

30 Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, Fayad P, Katzen BT, Mishkel GJ, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(15):1493-1501.

31 McCarthy WJ, Wang R, Pearce WH, Flinn WR, Yao JS. Carotid endarterectomy with an occluded contralateral carotid artery. Am J Surg. 1993;166(2):168-171.

32 Rothwell PM, Slattery J, Warlow CP. Clinical and angiographic predictors of stroke and death from carotid endarterectomy: systematic review. BMJ. 1997;315(7122):1571-1577.

33 Veith FJ, Amor M, Ohki T, Beebe HG, Bell PR, Bolia A, et al. Current status of carotid bifurcation angioplasty and stenting based on a consensus of opinion leaders. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2 Suppl):S111-S116.

34 Paciaroni M, Eliasziw M, Kappelle LJ, Finan JW, Ferguson GG, Barnett HJ. Medical complications associated with carotid endarterectomy. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET). Stroke. 1999;30(9):1759-1763.

35 Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Birkmeyer JD, Bredenberg CE, Fisher ES. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279(16):1278-1281.

36 Roubin GS, New G, Iyer SS, Vitek JJ, Al Mubarak N, Liu MW, et al. Immediate and late clinical outcomes of carotid artery stenting in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: a 5-year prospective analysis. circ. 2001;103(4):532-537.

37 Endovascular versus surgical treatment in patients with carotid stenosis in the Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9270):1729-1737.

38 Hobson RW. CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stent Trial): background, design, and current status. Semin Vasc Surg. 2000;13(2):139-143.

39 Featherstone RL, Brown MM, Coward LJ. International carotid stenting study: protocol for a randomised clinical trial comparing carotid stenting with endarterectomy in symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18(1):69-74.

40 Ringleb PA, Kunze A, Allenberg JR, Hennerici MG, Jansen O, Maurer PC, et al. The Stent-supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy Trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:66-68.

41 EVA-3S Investigators. Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in patients with severe symptomatic carotid stenosis (EVA-3S) Trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:62-65.

42 Biasi GM, Froio A, Diethrich EB, Deleo G, Galimberti S, Mingazzini P, et al. Carotid plaque echolucency increases the risk of stroke in carotid stenting: the Imaging in Carotid Angioplasty and Risk of Stroke (ICAROS) study. circ. 2004;110(6):756-762.

43 Geroulakos G, Domjan J, Nicolaides A, Stevens J, Labropoulos N, Ramaswami G, et al. Ultrasonic carotid artery plaque structure and the risk of cerebral infarction on computed tomography. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20(2):263-266.

44 Levy EI, Hopkins LN. Editorial comment—Utility of abciximab during carotid stenting when distal protection is contraindicated. Stroke. 2003;34(11):2567.

45 Chan AW, Yadav JS, Bhatt DL, Bajzer CT, Gum PA, Roffi M, et al. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of emboli prevention devices versus platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition during carotid stenting. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(6):791-795.

46 Ohki T, Marin ML, Lyon RT, Berdejo GL, Soundararajan K, Ohki M, et al. Ex vivo human carotid artery bifurcation stenting: correlation of lesion characteristics with embolic potential. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27(3):463-471.

47 Jordan WDJr., Voellinger DC, Doblar DD, Plyushcheva NP, Fisher WS, McDowell HA. Microemboli detected by transcranial Doppler monitoring in patients during carotid angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy. Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7(1):33-38.

48 Berjljung L, Hjorth S, Svendler CA, Oden B. Angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1977;145(4):501-503.

49 Ecker RD, Guidot CA, Hanel RA, Wehman JC, Sauvageau E, Guterman LR, et al. Perforation of external carotid artery branch arteries during endoluminal carotid revascularization procedures: consequences and management. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17(6):292-295.

50 Broadbent LP, Moran CJ, Cross DTIII, Derdeyn CP. Management of ruptures complicating angioplasty and stenting of supraaortic arteries: report of two cases and a review of the literature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(10):2057-2061.

51 Wholey MH, Wholey MH, Tan WA, Toursarkissian B, Bailey S, Eles G, et al. Management of neurological complications of carotid artery stenting. J Endovasc Ther. 2001;8(4):341-353.

52 Coutts SB, Hill MD, Hu WY. Hyperperfusion syndrome: toward a stricter definition. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(5):1053-1058.

53 Rosenfield K, Babb JD, Cates CU, Cowley MJ, Feldman T, Gallagher A, et al. Clinical competence statement on carotid stenting: training and credentialing for carotid stenting—multispecialty consensus recommendations: a report of the SCAI/SVMB/SVS Writing Committee to develop a clinical competence statement on carotid interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(1):165-174.