Chapter 32 Carotid Artery Stenting

On May 6th, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) followed up on the January 2011 recommendation of the FDA Circulatory System Device Panel1 and approved the RX Acculink carotid stent (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, Calif.) for use in conjunction with Abbott’s embolic protection device (EPD), the Accunet filter. The expanded label as a result of the FDA’s approval was for treatment of extracranial carotid stenosis in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients who would otherwise be considered standard risk for surgical carotid endarterectomy (CEA). This was a landmark event because for the first time, carotid stenting, at least in the United States, qualified as a standard-of-care treatment and was no longer investigational or experimental for the majority of patients with carotid artery disease. (Earlier in [2004], the FDA had approved carotid artery stenting [CAS] for high CEA risk patients). This chapter reviews historical aspects and development of CAS, discusses stenting technique in detail, and reviews clinical trial data that support current indications for this procedure.

Historical Perspective

Carotid Endarterectomy

Surgical treatment for carotid artery stenoses was introduced in the early 1950s.2 Although early observational data suggested benefit for surgery over medical therapy, large prospective randomized trials investigating the beneficial effect of CEA on stroke reduction were not initiated until the late 1980s and early 1990s. Landmark studies including the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET),3–6 European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST),7 Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS),8 and Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST)9 confirmed the benefits of surgery over best available medical treatment for reducing the risk of stroke in both symptomatic (NASCET, ECST) and asymptomatic patients (ACAS, ACST). Carotid endarterectomy surgery is comprehensively discussed in Chapter 33.

Patients included in these surgical studies were carefully selected; specifically, subjects who were considered high CEA risk were excluded from participation. Thus, octogenarians, patients with recurrent stenosis following prior ipsilateral endarterectomy, intracranial stenosis that was more severe than the surgically accessible lesion in the neck, unstable angina pectoris, recent myocardial infarction (MI), contralateral CEA, patients on long-term anticoagulation therapy, and surgically inaccessible lesions were all excluded from these trials.3,8

Endovascular Approaches to Treat Carotid Stenosis

The mission to develop safer percutaneous endovascular solutions to treat arterial stenosis was pioneered by Dotter10 and Gruntzig and Hopff11 in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1977, Klaus Mathias, an interventional radiologist, described a catheter system that could be used for performing balloon angioplasty of cervical carotid stenosis,12 and this was followed by a few case reports of successful carotid angioplasty performed in the surgical suite.13,14 In 1984, Vitek and his neuroradiology colleagues from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)15 reported angioplasty of the innominate artery aided by balloon occlusion protection of the common carotid artery (CCA). This early report represents the first percutaneous intervention performed with the benefit of distal embolic protection. During the 1980s, clinical reports of carotid angioplasty were sporadic and limited to small single-center series of patients.16 Kachel et al. summarized the results of carotid angioplasty published in the literature through 1995 and noted that 503 of the 523 (96%) procedures were technically successful. There were no deaths, major strokes occurred in 2.1%, and minor complications were in the single digits (6.3%).17 In 1985, Rabkin and Germashev began using early-generation nitinol (an alloy of nickel and titanium) stents as an endovascular prosthesis and subsequently reported their 5-year experience.18

In March 1994, Iyer, Vitek, and Roubin initiated the carotid angioplasty program at UAB under carefully scrutinized institutional protocols.19 Initial interventions were performed using stand-alone balloon angioplasty (no stents). To maximize the luminal result, a long inflation was performed using a 5-mm over-the-wire balloon; the center port of this balloon could accommodate a 0.035-inch guidewire. Once the balloon was in place, the wire was withdrawn, and oxygenated arterial blood withdrawn from the femoral artery was infused through the center port of the balloon with the help of a special pump device, permitting a long 10-minute balloon inflation. The first four patients were treated without complications. Patient #5, a woman with contralateral carotid occlusion, presented with a transient ischemic attack (TIA) related to a high-grade stenosis in the index carotid artery and underwent an uncomplicated balloon angioplasty procedure. Despite a perfectly acceptable angiographic result, approximately an hour after the procedure, there was acute closure of the angioplastied carotid artery. Although a technically successful, urgent reintervention with recanalization and stenting of the occluded vessel was performed, the patient did not recover from the major stroke related to the acute closure and subsequently expired. This case triggered the decision by the UAB group to perform elective carotid stenting—irrespective of the angiographic results of balloon angioplasty—and primary stenting became the intervention of choice for treatment of cervical carotid stenosis. The subsequent rapid adoption of this approach by interventional cardiologists in particular, and the endovascular interventional community in general, heralded the modern era of endovascular treatment for extracranial carotid bifurcation disease.19–22

Although balloon expandable stents were used in the first 100 patients, by the summer of 1995 (when the initial patients returned for their follow-up angiograms) it became clear that these stents were prone to deformation (stent crush) because of the superficial location of the carotid artery and the associated movements of the neck.23 The Alabama group were the first to report this complication, seen in approximately 15% of patients at 6-month follow-up.23 Fortunately, stent deformation was largely a cosmetic issue, with only one patient presenting with symptoms in this series. This observation, as well as the recognition that chances for regulatory approval for balloon expandable stents for treating extracranial carotid stenosis were slim, led to the rapid introduction, testing, and adoption of self-expanding stents. Stents have all but abolished acute carotid vessel closure, and in contemporary practice, primary carotid stenting is the norm. The reader should note that unlike in coronary arteries, the risk of acute stent thrombosis and instant restenosis, two major limitations of coronary stents, are nonissues when stents are deployed in the extracranial carotid location.

In 1996, Theron et al.24 reported results from his seminal work using his triple coaxial catheter that incorporated distal balloon occlusion for providing embolic protection during carotid bifurcation angioplasty. Unfortunately, this early-generation distal protection balloon could only be used with balloon angioplasty (and not with stents). By 2000, the first investigational distal balloon occlusion EPD, the Percusurge Guardwire (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn.) was introduced into clinical trials in the United States. This was soon followed by a number of clinical trials, all of which included a filter as the distal EPD. Unlike Theron’s distal occlusion balloon, the Percusurge balloon—as well as all such filters—can be used with both over-the-wire and monorail stent delivery systems. As increasing clinical data became available, use of distal protection devices was recognized and accepted by many (but not all25) as an integral if not mandatory part of carotid artery dilation and stenting.26–31 In our opinion, EPDs, when selected and used appropriately, improve procedure safety by significantly reducing the risk of procedure related embolic major and fatal strokes.

The multicenter Carotid and Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS-I)9 was conducted between 1992 and 1997 in the United Kingdom during an era when stents were neither widely available nor perceived as integral. This prospective randomized trial compared outcomes of balloon angioplasty and CEA in 504 patients; only 55 patients (26%) within the group assigned to endovascular treatment received stents. Initially, stents were used only as a bailout treatment, with increased elective use toward the end of the study; distal protection devices were not used. Major event rates within 30 days after treatment did not differ significantly between endovascular treatment and surgery: disabling stroke or death (6.4% vs. 5.9%) and any major stroke lasting more than 7 days or death (10.0% vs. 9.9%). This study also demonstrated that endovascular techniques were superior to surgery when considering other risks related to the incision in the neck and use of general anesthesia. Cranial nerve injury was reported in 8.7% of surgical patients; no events occurred in patients undergoing endovascular procedures (P < 0.0001). Major groin or neck hematomas occurred less often after endovascular treatment than after surgery (1.2% vs. 6.7%, P < 0.0015). The results of this early clinical trial set the stage for investigation of carotid stenting.

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for carotid artery revascularization have been well delineated in the recent American Stroke Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ASA/ACCF/AHA) et al. Guideline on the Management of Patients with Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease32 and essentially depend on symptomatic status and severity (degree) of stenosis. Hence, before an informed decision on a treatment option can be made (surgery or percutaneous intervention), it is critically important for patients and physicians to have a good understanding of the operator as well as the center’s procedural and 30-day experience and outcomes.

Symptomatic Patients

It is well accepted that revascularization should be offered to all symptomatic patients if the diameter of the ICA is reduced more than 70% as documented by noninvasive imaging, or more than 50% as documented by catheter angiography (Table 32-1). There is, however, one important caveat: the periprocedural risk of stroke or death related to the revascularization procedure (CEA or CAS) should be under 6%.32 In symptomatic patients, there is a well-established correlation between increasing stenosis severity and stroke risk. The NASCET study3 demonstrated the benefit of CEA over medical treatment for reducing the risk of future stroke in symptomatic patients with carotid stenosis between 70% and 99%. The NASCET results also showed that symptomatic patients with a lesser degree of stenosis (between 50% and 70%) benefit less. Revascularization is typically recommended in this group if there are additional unfavorable angiographic features (e.g., ulceration or other features associated with increased risk of vessel-to-vessel embolization).

Table 32-1 Modified American Heart Association Recommendations for Carotid Artery Revascularization

| Indication Level | Symptomatic Stenosis* | Asymptomatic Stenosis* |

|---|---|---|

| Proven | 70%-99% stenosis | >80% stenosis |

| Periprocedural complication risk <6% | Periprocedural complication risk <3% | |

| Life expectancy >5 years | ||

| Acceptable | 50%-69% stenosis | >60% stenosis |

| Periprocedural complication risk <3% | Periprocedural complication risk <3% | |

| Planned CABG | ||

| Unacceptable | <49% stenosis or | <60% stenosis or |

| Periprocedural complication risk >6% | Periprocedural complication risk >5% |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

* Lesion severity is determined according to the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) methodology (i.e., the ratio between lumen diameter at the point of maximal stenosis and the lumen diameter of the non tapered segment of the distal internal carotid artery).153

Modified from Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al: ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery, developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 57:1002–1044, 2011; and Roubin GS, Iyer S, Halkin A, et al. Realizing the potential of carotid artery stenting: proposed paradigms for patient selection and procedural technique. Circulation 113:2021–2030, 2006.

An important, albeit controversial and unsettled, issue in the treatment of symptomatic patients relates to the timing of the revascularization procedure after the index symptomatic event.33–37 Risk of a recurrent neurological event after a TIA or stroke is estimated to be between 15% and 20%, and this elevated risk persists for approximately 6 months after the initial event and underlies the rationale for the 6-month threshold for defining symptomatic patients. Proponents of early intervention i.e., within a few days of the symptomatic event. Argue that the highest risk of a recurrent event is during this early period and any delay in treatment will significantly diminish its therapeutic value, since a substantial portion of these patients would have already experienced a neurological event during the waiting period. A key reason underlying the reluctance of operators to perform revascularization (CEA or CAS) soon after a stroke (less so after a TIA) is the concern that early treatment increases the risk of hemorrhagic transformation of the culprit, (nonhemorrhagic) infarct. Although the increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage following early intervention has been challenged,33 a recent retrospective analysis38 of a large national inpatient database involving more than 57 million in-hospital admissions, conducted to determine the prevalence and risk factors of intracranial hemorrhage among patients undergoing CEA (N = 215,012) and CAS (N = 13,884), arrived at a different conclusion. Symptomatic presentations represented the minority of indications for CEA (n = 10,049 [5%]), as well as CAS (n = 1251 [10%]). Intracranial hemorrhage occurred significantly more frequently after CAS than CEA in both symptomatic (4.4% vs. 0.8%; P <0.0001) and asymptomatic presentations (0.5% vs. 0.06%; P <0.0001). Multivariate regression suggested that symptomatic presentations (vs. asymptomatic) and CAS procedures (vs. CEA) were both independently predictive of six- to sevenfold increases in the frequency of postoperative intracranial hemorrhage. The observations from this retrospective population-based analysis are at variance with observations from recent large prospective randomized trials involving symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, wherein the risk of mortality and major stroke was uniformly low in both CEA and CAS arms, and the higher incidence of neurological events in the CAS arm was a result of minor strokes (ischemic rather than hemorrhagic).39–41 Pending resolution of this issue by future studies, the current approach of waiting a minimum of 3 weeks following the index event (longer for larger strokes) is likely to continue.

Asymptomatic Patients

Asymptomatic carotid disease refers to the presence of a stenosis resulting in a 60% or greater reduction of the luminal diameter of the extracranial ICA without symptoms of ipsilateral stroke, TIA, or amaurosis fugax. Treatment of patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis has become extremely controversial, with two main issues fuelling this ongoing debate42–44:

1. Which asymptomatic patients (if any) are appropriate for intervention (CEA or CAS)? Current guidelines suggest that it is reasonable to refer asymptomatic patients for ICA revascularization in the setting of more than 80% stenosis and low periprocedural risk.32

2. What should be the choice of treatment? In the event revascularization is to be performed in an asymptomatic patient, should the patient be referred for CEA or CAS?

Medical treatment vs. intervention (CEA/CAS) for asymptomatic carotid disease

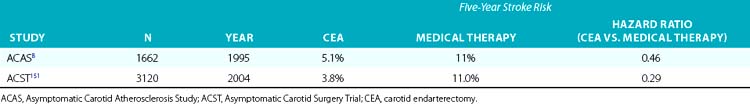

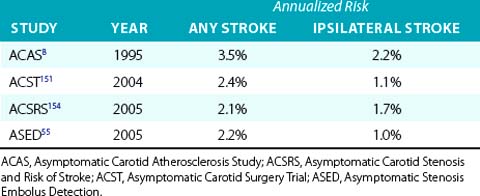

Despite publication of several guidelines that provide a best assessment of current research, considerable divergence of opinion regarding care of the carotid artery remains an issue among physicians worldwide.45 One reason why enthusiasm for revascularization may be low is recognition that the annualized risk of a stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery disease treated with contemporary medical treatment is low and dropping (Table 32-2). This reduction in stroke risk has been attributed to the benefits of risk-factor modification, use of antihypertensive medications,46 antiplatelet agents,47 smoking cessation, and statin therapy.48,49

Table 32-2 Annualized Stroke Risk in Asymptomatic Patients with Greater Than 50% Carotid Artery Stenosis Treated with Best Medical Therapy Available During Trial Period

The guidelines respond to this concern by limiting revascularization to those asymptomatic patients in whom periprocedural risk of a stroke or death is expected to be below 3%.32 Hence, some clinicians argue that there is an urgent need for a new three-arm randomized clinical trial for asymptomatic carotid disease that includes not only CEA and CAS but also has a medical treatment arm. A critical message from the asymptomatic CEA trials was that for surgical revascularization to be beneficial in reducing future stroke risk in asymptomatic patients (Table 32-3), the periprocedural risk of revascularization should not exceed 3%. If the risk breaches the 3% threshold, the difference in stroke risk between the medically treated arm and the surgical arm will not be significant (i.e., the benefit of stroke reduction from the surgery no longer accrues to the patient). The second Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST II) will be a three-arm study involving asymptomatic patients, and this protocol is currently under review for funding by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Identifying the asymptomatic patient at high risk for developing a stroke

Much of the controversy surrounding treatment of asymptomatic carotid stenosis could be resolved if physicians had a method of reliably identifying the asymptomatic patient at high risk for a future stroke; interventional treatment could then be selectively directed at these patients. Understandably, such an approach would greatly improve the yield and cost-effectiveness of prophylactic invasive treatment with either CEA or CAS.50 Some of the metrics that have been proposed as predictors of increased risk of ipsilateral ischemic events in asymptomatic patients with carotid stenosis include higher grades of stenosis or substantial progression of carotid stenosis to a higher grade,51,52 unfavorable plaque characteristics and composition, including plaque ulceration and echolucency,53,54 or verifying the presence or absence of microemboli by using transcranial Doppler.55–58 Other clinical and radiological markers for predicting an increased risk of stroke in asymptomatic patients include occult cerebral infarction on brain imaging studies,59 contralateral carotid occlusion,60 or detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).61 Nicolaides et al.62 have suggested that combining clinical risk factors, such as diabetes and smoking, with high-risk ultrasound features (e.g., echolucent plaque) may help identify the high-risk asymptomatic patient. These are listed in Table 32-4.

Table 32-4 Postulated Clinical/Investigative Features to Identify High Stroke Risk Patients with Asymptomatic Carotid Disease

| Criteria | Author(S)/Reference |

|---|---|

| Anatomical | |

| High-grade carotid stenosis with substantial progression | Bock,51 Hirt52 |

| Contralateral carotid occlusion | AbuRahma60 |

| Plaque Characteristics | |

| Plaque composition, ulceration, or echolucency | Nicolaides,53 Spence54 |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage | Altaf 61 |

| Plaque composition and clinical risk factors | Nicolaides62 |

| Imaging | |

| Microembolization | Abbott,55 Markus,56 Spence57,58 |

| Occult cerebral infarction | Norris59 |

• Contralateral carotid occlusion and a stenosis between 60% and 80% in the index carotid artery that also supplies the territory of occluded carotid artery via collaterals.

• Bilateral greater than 70% but less than 80% stenosis.

• Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography (CT) findings of clinically silent (asymptomatic) prior ipsilateral stroke(s).

• Patients scheduled to undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and/or valve surgery (especially if surgery will be performed on-pump).

In the absence of an established reliable method of identifying the asymptomatic patient with carotid stenosis at high risk for developing a future neurological event, the decision to treat is predominantly based on degree of stenosis, an approach supported by the large CEA clinical trials. The threshold for treating asymptomatic carotid stenosis is 80% or greater stenosis confirmed by angiography (NASCET criteria), with corresponding elevated duplex velocities. Although standard risk-factor modification approaches should be implemented in all these patients, there is no convincing evidence to date that risk-modifying measures by themselves will reduce stroke risk in patients with severe degrees of stenosis that cannot be further improved with revascularization when the periprocedural risk is 3% or less. This nonnegotiable low tolerance for periprocedural complications constitutes what the authors have framed as the 3% Rule of Carotid Stenting.63 How to avoid breaching this rule is central to the theme of patient selection for carotid stenting. The critical all-important task of identifying the standard-risk patient for carotid stenting (not CEA) is discussed later in the chapter.

Deciding on the type of intervention, CAS or CEA, is also discussed later.

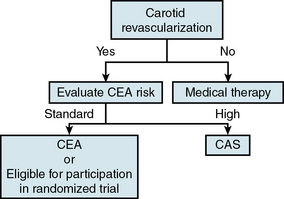

Patient Selection for Carotid Stenting

Procedure-Related Risks

Evolution in our understanding of the concept of high stent risk

To help the interventionist decide whether stenting is an appropriate treatment for a particular patient (and lesion), it is important for the operator to understand, recognize, and differentiate the standard-risk (Box 32-1) from the high-risk CAS patient. This determination, based on an individualized analysis, is the single most important element of the CAS risk stratification process and should be performed for every patient. The designation of high stent risk has evolved over time, and in retrospect was a critical component of the learning curve of the early adopters of the CAS treatment modality. Because the attributes that define high CEA risk (Box 32-2) are distinct from those that define high stent risk, a patient who is high risk for CEA does not automatically become suitable (i.e., standard risk) for CAS. The presence of high-risk features for stenting was unrecognized during the early clinical trials and the criteria for inclusion in these trials only specified “high–CEA risk patients,” thus permitting unbalanced comparisons of technique. Hence, the high event rates observed in early high–CEA risk stent registries resulted in large part from the unwitting inclusion of high stent risk patients. With the more recent exclusion of high stent risk patients, a corresponding improvement in procedural outcomes has been noted. For example, by 2005 the concept of high stent risk was better established, and in the second half of the CREST study, many of these high-risk stent patients were generally excluded (since the CREST protocol written in the late 1990s did not specifically call out high stent risk exclusions).39 The Asymptomatic Carotid Trial (ACT-I), a trial that specifically excludes high stent risk patients, is in progress (NCT00106938).

![]() Box 32-1 Standard Risk for Carotid Stenting: Patient and Lesion Characteristics

Box 32-1 Standard Risk for Carotid Stenting: Patient and Lesion Characteristics

Recognize Ideal Lesion and ICA Morphology for Carotid Stenting

Angle between the ICA and ECA is <90 degrees

Angle between the ICA and ECA is <90 degrees

Minimal vessel tortuosity (i.e., no carotid redundancy)

Minimal vessel tortuosity (i.e., no carotid redundancy)

No ulceration or obvious filling defects

No ulceration or obvious filling defects

Stenosis severity and whether plaque is concentric or eccentric are less important, as long as flow is normal (i.e. TIMI III)

Stenosis severity and whether plaque is concentric or eccentric are less important, as long as flow is normal (i.e. TIMI III)

Lesion located in a straight segment (as opposed to a bend) of the ICA

Lesion located in a straight segment (as opposed to a bend) of the ICA

Artery cephalad to the stenosis is straight (minimal bends and vessel tortuosity)

Artery cephalad to the stenosis is straight (minimal bends and vessel tortuosity)

![]() Box 32-2 Anatomical Features and Comorbidities Associated with High Carotid Endarterectomy Risk

Box 32-2 Anatomical Features and Comorbidities Associated with High Carotid Endarterectomy Risk

Anatomical

Surgically inaccessible lesions above C-2 or below the level of the clavicle

Contralateral carotid artery occlusion

Restenosis after a previous ipsilateral CEA

Previous head/neck radiation therapy or surgery that included the area of stenosis

Ipsilateral radical neck dissection for the treatment of cancer

Comorbidities

Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a forced expiratory volume (FEV) 1 less than 30%

Requirement for staged and scheduled coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or valve replacement procedures more than 30 days following the stent procedure

Recent myocardial infarction more than 72 hours and less than 30 days

Two or more major diseased coronary arteries that require revascularization (70% or more)

Standard stent risk

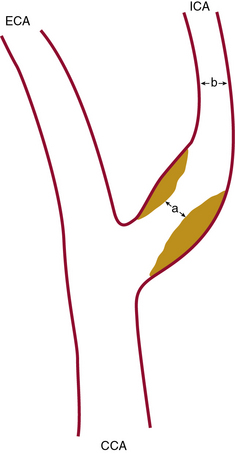

Close attention should be paid to the end-diastolic ultrasound flow velocity. If this value exceeds 100 cm/s (especially >120 cm/s), the angiographic stenosis severity will exceed 80% (as defined by the NASCET criteria; Fig. 32-1) and will meet the treatment threshold for treating asymptomatic lesions.

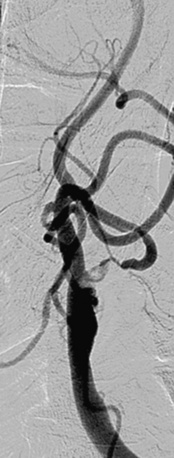

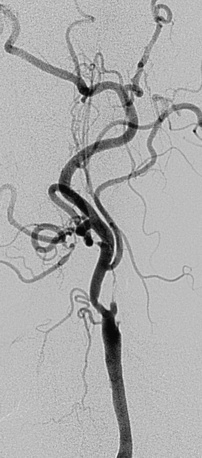

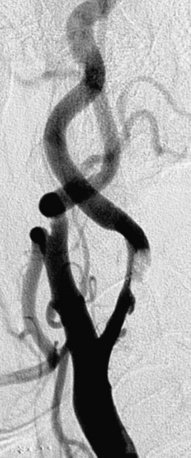

Figure 32-2 illustrates lesion and vessel features that are ideal for stenting using distal embolic protection. These features include:

• A narrow acute angle between the ICA and external carotid artery (ECA). The wider this bifurcation (i.e., the angle approaches 90 degrees or is frankly obtuse), the greater the technical difficulty in advancing a distal embolic protection filter device with a fixed-wire system (Fig. 32-3). The technical difficulty imparted by an open ICA/ECA angle is compounded if there is additional tortuosity in the ICA distal to the stenosis (Fig. 32-4).

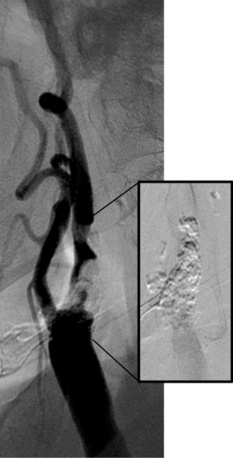

• Minimal calcification and no ulceration. Some degree of calcification is nearly ubiquitous in a diseased carotid bifurcation, but heavy concentric calcification in association with a severe stenosis is a major problem. Although the demonstration of carotid calcification is straightforward and requires only fluoroscopy (Fig. 32-5), the distinction between deep vessel wall calcium and superficial calcium encroaching on the vessel lumen may be difficult, and the decision to declare the case unsuitable for CAS is largely subjective. We arbitrarily define heavy calcification as calcification 3 mm or more in width, with concentricity defined by imaging in two orthogonal views. The unyielding nature of calcium, along with the stiffness it imparts to the involved vessel segment, makes it difficult to predilate and advance the EPD and stent delivery system through the lesion (especially the stent). Forcing these devices in an attempt to cross the stenosis not only increases the chances of prolapsing the sheath out of the CCA, it also increases the risk of embolization, spasm, and dissection. Inability to completely dilate and expand the deployed stent despite using larger and/or high-pressure balloons (resulting in a stent with an hourglass appearance) is an intraprocedural nightmare.

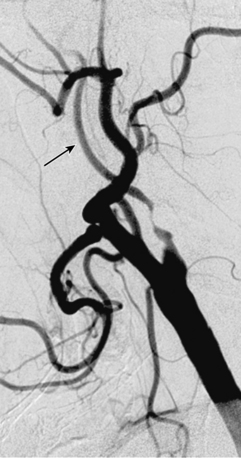

• The artery, especially cephalad to the stenosis, is free of any significant kinks or bends. Presence or absence of this key unfavorable feature is extremely important to note on preprocedure magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or invasive angiography, since it increases the degree of difficulty when attempting to place a distal filter EPD. Excessive vascular tortuosity is defined as two or more bend points that are 90 degrees or greater (see Fig. 32-4). At times the tortuosity can be extreme and may impart a hairpin bend to the ICA (see Fig. 32-4). Worsening grades of tortuosity increase the difficulty when attempting to cross the stenosis and may make device delivery difficult or impossible. Straightening of the tortuous vessel segment by stiff wires or devices may result in vessel spasm and reduced antegrade flow. Thus, despite filter placement, the patient does not receive the benefit of brisk antegrade flow and may manifest ischemic symptoms in the absence of adequate collaterals. Additionally, slow flow increases the risk of fibrin deposition within the filter. The longer the dwell time of the EPD, the higher the risk of an iatrogenic thrombus. Iatrogenic tortuosity can also be introduced by placement of the sheath in a redundant carotid artery, so tortuosity should be assessed after the sheath is in place below the carotid bifurcation.

Figure 32-3 These lesions are unsuitable for carotid artery stenting using a distal embolic protection device.

Stenosis severity and eccentricity/concentricity are not problems as long as the flow in the vessel is normal (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] grade III). A severe stenosis in association with less than TIMI III flow (string sign, Fig. 32-6) and an occluded artery are contraindications (Fig. 32-7) for CAS. Ulceration is often noted, even on angiograms from asymptomatic patients, and although not a contraindication, operators should be aware that the risk of embolization might be higher, particularly during the phase of poststent balloon dilation. Angiographic filling defects that are consistent with a thrombus are a contraindication to CAS (Fig. 32-8). Note that both calcium and thrombus may appear as filling defects, and the differentiation is based on the clinical presentation. Whereas a filling defect in a symptomatic patient should be presumed to be thrombus (see Fig. 32-7), filling defects in asymptomatic patients are frequently a result of calcium encroaching on the vessel lumen (Fig. 32-9).

Figure 32-7 Thrombus located in proximal internal carotid artery in a patient with symptomatic carotid artery disease.

This is identified by the hazy appearance and is only visible following contrast injection.

Figure 32-8 This patient demonstrates eccentric calcification, which may at times closely resemble thrombus.

Fluoroscopy without contrast injection will typically reveal calcification, as also shown in Figure 32-5.

As a rule, unfavorable anatomical features (Figs. 32-10 and 32-11; also see Figs. 32-3 through 32-9) should be considered contraindications for CAS. Although special techniques (e.g., use of a heavy-gauge buddy wire to straighten tortuous vessel segments, use of cutting balloons to dilate unyielding lesions) may result in a satisfactory angiographic outcome, the risk of a procedure-related neurological event should be presumed to breach the accepted periprocedural complication threshold.

Procedural Considerations for Carotid Artery Stenting

Initial Evaluation

Antiplatelet Agents and Anticoagulants

In the clinical protocol, great emphasis is placed on dual antiplatelet therapy before and after carotid stenting. The non-event of stent thrombosis and the low rates of peri- and postprocedural embolic events are predicated upon administration of the correct doses of adjunctive antiplatelet therapy. All patients should receive aspirin, 81 to 325 mg daily, and clopidogrel, 75 mg daily, prior to the procedure and for a minimum of 30 days after the procedure.32 If a patient has not received both aspirin and clopidogrel on a daily basis, we suggest they receive a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel at least 4 hours prior to the procedure. If this is not possible, the procedure should be rescheduled. There is no experience using prasugrel in patients undergoing carotid stenting.

Technique of Carotid Stenting

Technical aspects of the procedure are discussed under the following headings:

• Diagnostic Angiographic Evaluation.

• Final Angiographic Assessment.

• Embolic Protection Device and Sheath Removal and Access Site Hemostasis.

Diagnostic Angiographic Evaluation

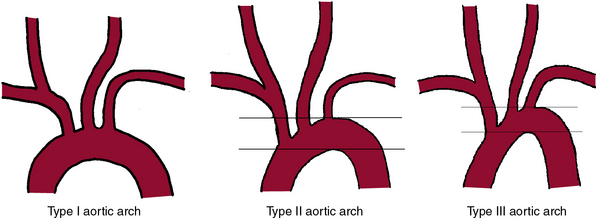

It is mandatory to have a high-quality complete diagnostic cerebral and extracranial carotid angiogram prior to initiating the stenting procedure. Imaging of the aortic arch by angiography, MRA, or CTA may be helpful to define the arch type and anomalous origins of the vessels. The most common anomaly, seen in approximately 7% of patients, is independent origin of the left vertebral artery from the arch and origin of the left carotid artery from the innominate. Figure 32-12 shows classification of the aortic arch.

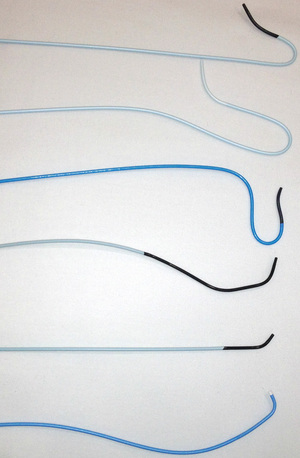

Catheter selection for diagnostic angiography

A variety of catheters are available for diagnostic cerebral angiography, and selection is tied to operator familiarity and experience. Examples of diagnostic catheters are shown in Figure 32-13. It should be understood that catheters that require additional manipulations to reshape them within the ascending aorta increase the risk of embolization. Use of such catheters should be reserved for negotiating the difficult aortic arch anatomy (e.g., patients with extended, stiff, calcified aortas [see Fig. 32-12, type III arch]) when use of alternative preshaped catheters that require less manipulation have either failed or are expected to fail.

1. It is a reliable, reproducible method for precisely measuring the degree of carotid artery stenosis (see Fig. 32-1).

2. It demonstrates anatomical conditions that can be unfavorable for carotid stenting. Examples include dilated/extended aortic arch (see Fig. 32-12), marked vessel tortuosity, heavily calcified stenosis, and lesions with obvious filling defects (see Figs. 32-3 through 32-11).

3. It helps define the status of collateral circulation to the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere (i.e., the one supplied by the stenotic carotid artery being evaluated for treatment). Knowledge of contralateral carotid stenosis or occlusion and status of the collateral supply influences the stenting technique: shorter balloon inflations, for example, and choice of protection device—flow interrupting (occlusion balloon) vs. flow preserving (filter devices). The term isolated hemisphere describes the anatomical situation where the cerebral hemisphere of interest is entirely dependent on the ipsilateral ICA for its blood supply, owing to absence of the anterior and posterior communicating arteries.

4. It reliably demonstrates significant flow-limiting stenosis distal to the carotid bifurcation. Although the bifurcation stenosis may be treatable, the ultimate benefit of stroke reduction may not accrue to the patient because of additional cephalad disease.

5. In the event there is an intraprocedural neurological event, the postevent intracranial angiograms can be compared with the baseline preprocedure pictures.

The main risks of invasive cerebral angiography relate to the use of contrast and the possibility of a neurological event. The typical sequence of acquisition and the usual angiographic views are listed in Box 32-3.

![]() Box 32-3 Overview of Carotid Angiography Acquisition Views

Box 32-3 Overview of Carotid Angiography Acquisition Views

Left Subclavian Angiogram (PA View)

The ostium of the left vertebral artery is usually seen well in the frontal projection; if not, the RAO-cranial projection should be tried.

The ostium of the left vertebral artery is usually seen well in the frontal projection; if not, the RAO-cranial projection should be tried.

If a selective angiogram of the left vertebral artery is to be acquired, a roadmap to facilitate entry and selective placement of the catheter is recommended.

If a selective angiogram of the left vertebral artery is to be acquired, a roadmap to facilitate entry and selective placement of the catheter is recommended.

Selective or nonselective intracranial views of the vertebrobasilar system are acquired in the lateral and steep AP cranial views.

Selective or nonselective intracranial views of the vertebrobasilar system are acquired in the lateral and steep AP cranial views.

Selective Left Carotid Angiograms

The bifurcation is imaged in LAO 45-degree as well as lateral projections. If the bifurcation is “overrotated,” an AP caudal view usually separates the external and internal carotid arteries very well.

The bifurcation is imaged in LAO 45-degree as well as lateral projections. If the bifurcation is “overrotated,” an AP caudal view usually separates the external and internal carotid arteries very well.

Intracranial images of the left carotid artery are acquired in the lateral and AP cranial (15- to 30-degree) views.

Intracranial images of the left carotid artery are acquired in the lateral and AP cranial (15- to 30-degree) views.

Selective Right Carotid Angiograms

Bifurcation is imaged in the RAO 45-degree as well as lateral projections.

Bifurcation is imaged in the RAO 45-degree as well as lateral projections.

Intracranial images of the right carotid artery are acquired in the lateral and AP cranial (15- to 30-degree) views.

Intracranial images of the right carotid artery are acquired in the lateral and AP cranial (15- to 30-degree) views.

AP, anteroposterior; LAO, left anterior oblique; PA, posteroanterior; RAO, right anterior oblique.

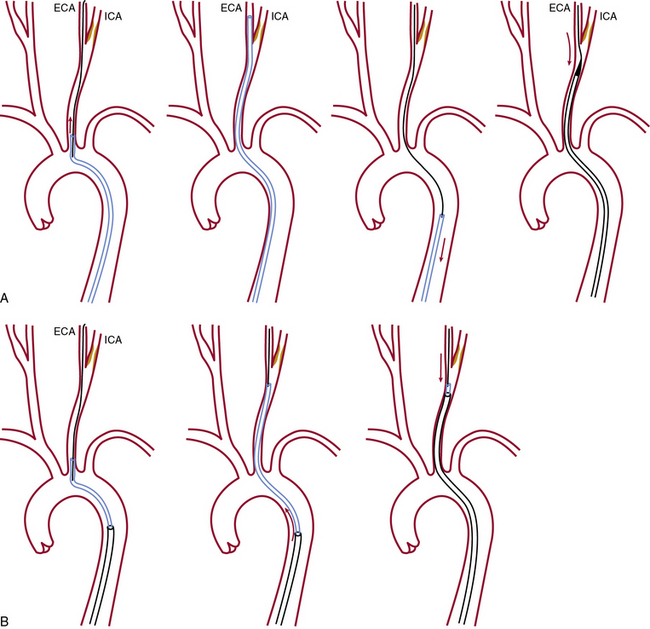

Carotid Sheath Placement

Once the diagnostic study is completed, the ICA with the target stenosis is identified, and there are no anatomical contraindications for stenting, a 90-cm long, 6 F sheath is advanced into the CCA using one of two techniques shown in Figure 32-14.

Advantages of the coaxial sheath technique

The coaxial sheath technique has a number of advantages:

1. It permits continuous access to the CCA once the sheath is in the CCA below the bifurcation.

2. Once the sheath is placed in a suitable spot below the bifurcation of the CCA, unfavorable anatomy (elongated arch, tortuosity of the CCA) will not impact the technical success of the procedure.

3. When passing the guidewire through the stenosis is difficult (eccentric stenosis, ulcerations, ICA kinks and tortuosity, or angulated takeoff of the ICA) or in the event of a complication (dissection, intracranial embolism), the coaxial configuration offers more support and allows easy introduction of other interventional tools.

4. The sheath carries a large-bore Tuohy-Borst adaptor that permits catheter or other device introduction with minimal blood loss and minimal risk of air trapping. The side arm allows intermittent or continuous flushing and contrast injection and also allows for continuous intraarterial (IA) blood pressure monitoring.

5. The integrated dilator provides a good fit and a smooth transition, features that facilitate advancement of the sheath in the two-step technique with minimal scraping of the plaque at the origin of the great vessels/aortic arch.

Disadvantages of the coaxial system (sheath or guiding catheter)

There are also a few disadvantages to the coaxial system:

1. If the carotid artery is tortuous, placement of the sheath exaggerates existing kinks and redundancies, and the tortuosity, along with the carotid bifurcation, is frequently displaced cephalad. Although these disappear once the sheath is withdrawn, these iatrogenic problems can increase the complexity and technical difficulty of the stenting procedure.

2. Rarely, dissection of the innominate artery or CCA may result following advancement of the sheath over the 5 F diagnostic catheter (telescoping technique).

3. There is always the possibility of embolization during sheath placement, a part of the procedure that cannot be neuroprotected.

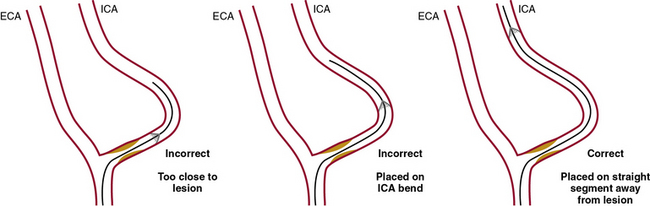

Embolic Protection Devices

Although not all steps of the carotid intervention can be “emboli protected” because placement of the sheath occurs prior to deployment of the EPD. It is important to recognize, however, that the risk of embolization is highest during stent deployment and balloon dilation.64

A number of EPDs are available and can be broadly divided into flow-interrupting (occlusive) and flow-preserving (nonocclusive) devices (Fig. 32-15). Occlusion EPDs can be subdivided into distal occlusion and proximal occlusion types. An example of a flow-interrupting EPD that is deployed distal to the stenosis is the Percusurge GuardWire (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn.). Proximal occlusion devices include those developed by Gore (Flagstaff, Ariz.) and the MoMa device (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn.). Although flow-interrupting occlusive-type EPDs are intuitively appealing (no blood flow = no emboli), some issues with their use have arisen. For example, to permit occlusion and interruption of antegrade flow in the ipsilateral carotid artery, it is mandatory to demonstrate robust collateral circulation to the hemisphere being treated. Infrequent use of the GuardWire device, as well as occasional device failure (inadequate balloon inflation and suboptimal seal of the carotid artery and/or premature deflation), has resulted in virtual abandonment of this device for carotid intervention. The rationale for use of proximal occlusion devices is based not only on interruption of antegrade flow but also flow reversal in the ipsilateral ICA. This combination is achieved by balloon occlusion of both the CCA and ECA. Although procedural outcomes using these devices are favorable,65,66 they are more in the category of a niche device, since the catheters are substantially larger. They are particularly useful in cases with tortuous distal ICA anatomies or lesions with filling defects that may embolize during wire passage prior to deployment of the distal EPD.

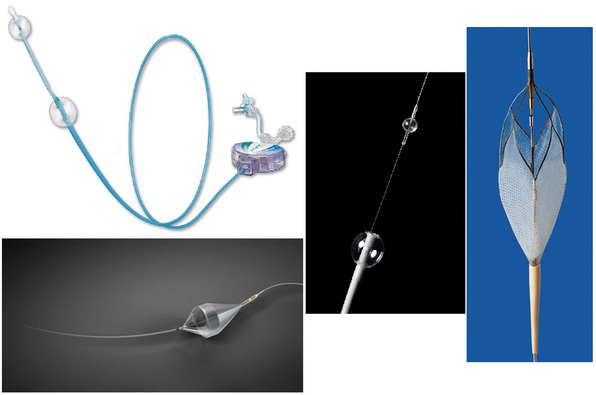

Embolic protection device deployment

The device has to be placed approximately 2 cm cephalad to the stenosis to provide adequate space (the “landing zone” for the EPD) to accommodate the tip of the stent delivery system and allow satisfactory coverage of the lesion with the stent (Fig. 32-16).

Lesion Predilation

Lesion predilation should be considered the default strategy because:

• Experimental studies using ex vivo models67 have demonstrated that large amounts of embolic debris are released with primary stenting without predilation.

• Postdilation of the constricted stent can worsen the scissoring effect of the stent wires on the plaque, increasing risk of embolization.

• Predilation facilitates smoother passage of the 5 F or 6 F self-expanding stent delivery system.

• Without predilation, the operator may find it difficult to withdraw the distal tip of the stent delivery system through the narrowed constricted portion of the stent.

• The narrowed stent may present problems during balloon passage for stent postdilation.

Stents

To eliminate the risk of deformation and crushing23 seen with balloon expandable stents, self-expanding stents are exclusively used for carotid stenting, with the following notable exceptions:

1. When treating an aorto-ostial stenosis of the CCA.

2. When the stenosis and treatment involve the distal portion of the cervical carotid artery (close to the skull base). There is minimal risk of stent deformation of a balloon expandable stent deployed at this level, and advancing the bulkier 5 F or 6 F self-expanding stent delivery systems to the distal ICA can be technically difficult.

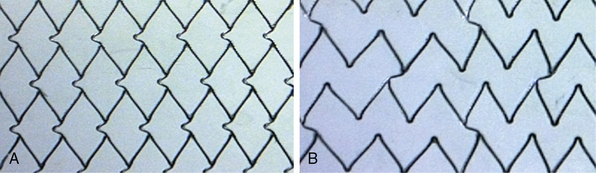

Although the Elgiloy (a cobalt chromium alloy) tracheobronchial Wallstent, (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.) was initially used, most operators currently use self-expanding nitinol stents. The Wallstent, an example of a closed-cell stent (see later discussion), fell out of favor largely because of its unpredictable foreshortening. This feature makes precise positioning of the stent very difficult. Despite structural and technical differences between the Elgiloy Wallstent and nitinol stents, there was no significant difference in carotid stenting outcomes using the Wallstent approved for use in the carotid circulation on the basis of the Boston Scientific EPI: A Carotid Stenting Trial for High-Risk Surgical Patients (BEACH) trial.68

Tips in stent selection, deployment, and positioning include:

1. If the lesion is on a bend, an open-cell (Fig. 32-17A) stent design should be selected (instead of a closed-cell design). Open-cell stents conform to the bend in the artery; a more rigid closed-cell (Fig. 32-17B) stent straightens the bend. Since the carotid artery is fixed at the skull base (as well as at its origin from the aorta), kinks and bends in the artery, a consequence of carotid redundancy resulting from elongation of the artery (seen with increasing frequency in the elderly hypertensive patient) cannot be eliminated by placing a stent in the kink. Instead, these kinks are displaced cephalad.

2. Deploying a closed-cell stent in a patient with significant tortuosity almost always results in a sharp angulation of the carotid artery immediately cephalad to the distal stent edge (Fig. 32-18). The stented portion of the artery appears as a straight segment.

3. An important technical point is to release the distal 3 to 5 mm of the stent and wait for the stent to expand fully and stabilize against the vessel wall before releasing the remainder of the stent. Nitinol stents have a tendency to jump distally if released too fast.

4. In our technique, the caudal end of the stent rests in the CCA, so a tapered stent with a diameter of 10 mm is preferred. Rarely, the stent is placed exclusively in the ICA. In this case, a 6- or 8-mm-diameter stent can be selected.

5. In almost all cases, the stent is placed across the bifurcation into the CCA and crosses the origin of the ECA. Covering the origin of the ECA with a stent rarely causes a lasting clinical problem. The ECA can be re-canalized if it becomes significantly stenosed or occluded after post-dilation of the stent, or if the patient is symptomatic (jaw or facial pain).

6. It is important to acquire an angiogram just prior to introducing the stent delivery system through the Touhey-Bourst adaptor. Stent deployment should be done using cervical spine bony landmarks as a guide (a road map can also be used to help guide stent deployment and positioning). Once the stent delivery system is in place across the carotid bifurcation, additional dye injections to help guide stent positioning are contraindicated. This is an important safety consideration because injecting dye with the stent delivery system in place (prior to releasing the stent) has been associated with an approximately 15% incidence of air embolism.

7. A closed-cell stent design (see Fig. 32-17), because of its smaller free cell area, gives the maximal and best circumferential wall coverage and a visually compelling angiographic result. Further, in our experience involving more than 2000 closed-cell nitinol stents, restenosis rates are very low. Some operators have proposed that the closed-cell structure can act as a barrier, preventing release of any additional embolic debris. Although open-cell stents (see Fig. 32-17) conform very well to the bends in the artery, there have been concerns that the stent struts projecting into the lumen of the artery may cause problems with recrossing the stent with the postdilation balloon an d/or EPD retrieval catheter. There are theoretical advantages and disadvantages to each of the two stent designs. Some have proposed that use of closed-cell stents may be associated with lower stroke and death rates when compared to stenting with open-cell designs.69,70 The issue is far from settled. Two recent publications showed no difference in either embolic load71 or long-term outcomes72 based on stent design. Additionally, there were no differences in outcomes in two large postapproval studies. The second phase of the Carotid RX Acculink/RX Accunet Post-Approval Trial to Uncover Unanticipated or Rare Events (CAPTURE 2; n = 4175) used the Acculink stent, an open-cell design from Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, California, and the Emboshield and Xact Post-Approval Carotid Stent Trial (EXACT; n = 2145) used Abbott Vascular’s Xact stent, a closed-cell design.73

Post-dilation

Post-dilation of the stent is a critical step:

1. It is possibly the time when the greatest number of emboli are released, and consequently the patient is at the greatest risk of stroke. The embolic load can be minimized by:

2. It is safer to underdilate than overdilate a self-expanding stent. Overdilation with a high-pressure balloon has the potential to squeeze the atherosclerotic material through the stent mesh, increasing the risk of distal embolization.

3. In some cases, a residual ulcer that is opacified by contrast flow through the stent struts is seen. No attempt should be made to obliterate this ulcer by using larger balloons or higher pressures in an effort to fill the ulcer crater with the stent. This communication (with the ulcer via the stent struts) will seal off and is of no clinical consequence.

Embolic Protection Device and Sheath Removal and Access Site Hemostasis

At the completion of the procedure, the sheath should be gently pulled back and out of the carotid artery and exchanged for a short sheath, which can be removed when hemostasis can be safely achieved. The vagal response to manual sheath removal and compression can compound the baroreflex effect of carotid stenting and lead to profound hypotension and bradycardia. In most patients, access-site hemostasis can be obtained using closure devices, although no improvement in outcomes has been demonstrated.74 Finally, although low blood pressure is not unusual in the immediate postprocedure phase, other causes (e.g., retroperitoneal hemorrhage related to access-site bleeding) should be considered as reasons for unexplained persistent hypotension.

Patients are monitored in a telemetry bed overnight, and more than 95% will be ready for discharge approximately 24 hours following the procedure. All patients should have a postprocedural neurological exam and assessment of the NIH and Rankin Stroke Scales. Once patients are able to ambulate without difficulty, they can be discharged with instructions to return for follow-up in 4 weeks (Box 32-4).

![]() Box 32-4 Discharge Protocol

Box 32-4 Discharge Protocol

Ambulate as tolerated next day.

Ambulate as tolerated next day.

NIH Stroke Scale before discharge.

NIH Stroke Scale before discharge.

Aspirin 325 mg PO daily for 1 month, then 81 mg PO indefinitely; clopidogrel 75 mg PO daily for a minimum of 4 weeks.

Aspirin 325 mg PO daily for 1 month, then 81 mg PO indefinitely; clopidogrel 75 mg PO daily for a minimum of 4 weeks.

Clinical evaluation at 1 month, 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter.

Clinical evaluation at 1 month, 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter.

Carotid duplex ultrasound at 1 month, 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter.

Carotid duplex ultrasound at 1 month, 6 months, 12 months, and yearly thereafter.

Neurological evaluation at 1 month and 12 months.

Neurological evaluation at 1 month and 12 months.

MRI (e.g., of cervical spine) is not contraindicated, since the stent is nonferromagnetic. However, follow-up MRA to evaluate stent status is contraindicated because there will be a dropout in the image within the stented segment (suggesting stent occlusion) related to the Faraday cage effect.

MRI (e.g., of cervical spine) is not contraindicated, since the stent is nonferromagnetic. However, follow-up MRA to evaluate stent status is contraindicated because there will be a dropout in the image within the stented segment (suggesting stent occlusion) related to the Faraday cage effect.

Patients who have received radiation treatment to the neck for malignancy should be on lifelong dual antiplatelet therapy.

Patients who have received radiation treatment to the neck for malignancy should be on lifelong dual antiplatelet therapy.

At discharge, decision to restart β-blockers, diuretics, and other antihypertensive medications is dictated by the hemodynamics. Almost all patients will be back on the preprocedure doses of these medications within a few days of discharge.

At discharge, decision to restart β-blockers, diuretics, and other antihypertensive medications is dictated by the hemodynamics. Almost all patients will be back on the preprocedure doses of these medications within a few days of discharge.

Maintain meticulous follow-up records and a database to enable tracking patient outcomes.

Maintain meticulous follow-up records and a database to enable tracking patient outcomes.

Management of Hemodynamics

1. Antihypertensive drugs, such as β-blockers and diuretics, are withheld on the morning of the procedure. The opening systolic pressure (i.e., pressure at the beginning of the procedure) may be elevated. Typically this is not treated; the first balloon inflation will reduce heart rate and blood pressure.

2. Ensure that the patient has adequate venous access for fluid administration. Prophylactic placement of a temporary venous pacer is no longer practiced.

3. All patients receive a prophylactic dose of atropine immediately prior to the predilation step.

4. Hypotension is primarily managed by hydration with 0.9% saline infusion. Patients with severe aortic stenosis and those with severe CAD do not tolerate hypotension and bradycardia. We consider placement of a temporary transvenous pacemaker, and occasionally placement of an intraaortic balloon pump prior to the procedure in such cases. These can typically be removed at the conclusion of the procedure.

5. Pharmacological management of hypotension involves use of α-agonists like intravenous (IV) phenylephrine. If there has been significant reduction in blood pressure prior to the postdilation step, it is a good strategy to administer phenylephrine prior to balloon dilation. This will temporarily elevate blood pressure, and hemodynamic issues will not prevent the operator from performing a single inflation with the balloon inflated to the appropriate pressure.

6. We do not advocate use of dopamine. Although blood pressure will improve, there are also unwanted side effects of tachycardia and/or provocation of arrhythmias, which can be a problem in patients with underlying coronary artery disease.

Management of Neurological Complications

1. Occlusion of a proximal vessel segment (e.g., M1 or M2 segment). Intervention is generally required, since these patients are unlikely to make a spontaneous recovery.

2. Distal occlusion of a single small branch—best managed with conservative measures.

3. Normal appearance, no loss of branches—good prognosis for full recovery of function.

4. Slow flow and/or appearance of emboli in multiple branches—prognosis is guarded, and chances for full recovery are generally poor.

Cerebral Hyperperfusion Syndrome

Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome (CHS) is a rare but serious complication of carotid revascularization. Following successful carotid revascularization, there is an increase in ipsilateral blood flow to the affected cerebral hemisphere. Most often the patient remains asymptomatic75; however, in some patients this increase can overwhelm normal compensatory mechanisms, resulting in a marked increase in flow. Cerebral hyperperfusion is defined as an increase in blood flow of greater than 100% from baseline, and CHS is hyperperfusion associated with neurological deficit. Estimated incidence varies according to methodology and definitions, but most published studies report a rate less than 3%.76

The pathophysiology of CHS is not completely understood but is most likely due to a combination of factors. Patients with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion have maximal dilation of the intracranial arterioles, and normal autoregulation may not be restored for several days or weeks following revascularization. Impaired autoregulation refers to failure of the brain at the microcirculatory level to modulate blood flow and blood pressure such that sudden increase in flow and pressure is not transmitted to small blood vessels. Rather, pressure and flow are maintained within a narrow range. Impaired autoregulation of small-vessel cerebral blood flow (CBF) has been implicated in CHS in experimental models. This is either due to endothelial dysfunction resulting from free radical accumulation,77 or neurogenic failure of smooth-muscle regulation.78 Failure of the normal baroreceptor reflex is another possibility, with uncompensated postprocedural hypertension contributing to hyperperfusion.79 Impairment of the trigeminovascular reflex may also contribute because it plays a role in maintaining normal cerebrovascular tone.80 Hyperperfusion results in fluid entering the interstitial space and causing edema, predominantly in the posterior circulation.

Those with severe (>90%) subocclusive stenosis, with limited collateral supply (isolated hemisphere), are most at risk for hyperperfusion.81 Baseline severe hypertension and persistence of increased blood pressure in the postprocedure period (not uncommon in patients postendarterectomy) can result in hyperperfusion lasting several days following a procedure.81

The most common clinical symptom of cerebral hyperperfusion is headache. Not uncommonly, patients report this symptom on the table soon after the procedure is completed. The headache may last a few days, is typically unilateral, and is associated with a nonfocal neurological exam. A more serious presentation, possibly related to cerebral edema, is seizure. Patients with CHS can present with a variety of neurological deficits, including isolated speech disturbance. In patients who develop neurological symptoms following carotid revascularization, other etiologies must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Differentiation must be made between procedure-related embolic complications with an ischemic infarct, manifestation of a low-flow state, and a high-flow state characteristic of CHS. The diagnosis of CHS is best confirmed with MRI.76

Treatment involves lowering blood pressure, reduction in cerebral edema, and anticonvulsant therapy. Because vasorelaxation may further increase cerebral blood flow, calcium antagonists and nitrates are contraindicated in the treatment of CHS. Hence, the operator must resist the urge to administer nitrates to relieve spasm (e.g., at the site of deployment of the EPD noted on the postprocedure angiogram); it will resolve gradually with time. Although nitrates will rapidly resolve spasm, they can also predispose to development of hyperperfusion. Owing to their ability to reduce cerebral perfusion pressure, labetalol and clonidine76,82 are the preferred agents. Duration of therapy is not well defined; treatment may be needed for several days or months post procedure.83 There is insufficient evidence to support the treatment of cerebral edema, although corticosteroids and barbiturates have been used to good effect. Prophylactic anticonvulsant treatment is not recommended but should be introduced if seizures occur.76

The relative infrequency of this condition and the heterogeneity of presentations make it hard to generalize outcomes following CHS. However, the limited data from the CEA literature suggest that a third of patients may remain disabled following CHS,84 with others reporting mortality rates of up to 50%.85 Therefore, although rare, the diagnosis should be considered in all patients who develop neurological symptoms following carotid revascularization.

Results of Carotid Stenting without Embolic Protection

As was the case with other arterial percutaneous interventions, the evolution and availability of arterial stents transformed the procedure. By the early 1990s, prospective observational studies of carotid stenting had been initiated.21 From the outset, carotid stenting performed by experienced operators produced acceptable outcomes in terms of disabling stroke and death. Nondisabling neurological events were evident and clustered in patients with advanced age, complex aortic arch and ICA anatomies, and severe ICA stenoses.22,86 Recognition of the importance of patient selection and continued refinement of the technique, largely made possible by the introduction of devices dedicated for use in the extracranial carotid arteries, helped improve outcomes by minimizing neurological complications.

Numerous case reports and clinical series of carotid stenting without embolic protection have been published.20,22,87–93 An early report of 117 carotid stenting procedures by Diethrich et al.89 documented a 6.4% rate of periprocedural neurological events; most of these were transient ischemic events or minor strokes with eventual full recovery. A high rate of local adverse events was related to direct common carotid cervical access, a technique that has largely been abandoned.

Following this, there were several encouraging reports of outcomes from other experienced centers.20,22,87,88,90,91 These were mixed series of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with varying degrees of arterial stenosis. Asymptomatic patients were generally required to have more severe stenosis or additional evidence of compromised cerebral circulation.19,22,89 Some reports included CCA lesions, which are not easily accessible by surgical techniques.22,89,94,95 These studies reported very high rates (>95%) of procedural and stenting success, with periprocedural minor stroke rates of 1.6% to 4.8% and major stroke/mortality rates between 1% and 1.5%.

Reviews of the status of carotid artery stent placement prior to the introduction of EPDs were published in 199896 and 2000.87 These observational and unaudited data provided an overall perspective on the status of stenting at that time. Thirty-six centers participated in the survey, which included 5210 stenting procedures. These documented a technical success rate of 98.4%. The 30-day rates of TIAs, minor strokes, major strokes, and mortality were 2.6%, 2.5%, 1.4%, and 0.8%, respectively.87 It was noted that technical failures were usually related to inability to access the CCA (2%-7% of patients), and prolonged procedural time was associated with increased morbidity.96 These results in a large series of patients at high surgical risk were encouraging; rates of adverse outcomes were comparable to standard CEA risk patients treated with surgery.

Results of Carotid Stenting Using Embolic Protection

Periprocedural neurological events related to embolization during carotid arterial stent placement were not unexpected. In an effort to reduce the incidence of these adverse events, transcranial Doppler studies were performed to investigate which stages of the procedure were responsible for microemboli. Few particles are released during sheath placement, with a modest number during wire crossing and predilation. The majority of particles were found to be released from the atheromatous plaque during stent deployment and the postdilation procedure.64 The fragments consisted of plaque debris, fibrin and platelet aggregates, lipid vacuoles, and calcium fragments.31,97 These findings provided the basis for development and routine use of embolic protection systems during carotid stenting.

Carotid Stenting in High-Risk Carotid Endarterectomy Patients

In 1998, the Stroke Council of the AHA published a series of recommendations relating to the performance of CEA in patients with extracranial bifurcation carotid artery stenosis.98 These recommendations were based largely on the results of ECST,7 NASCET,3 and ACAS.80 These three large randomized clinical trials established the benefit of CEA over prevailing best medical treatment and have provided much of the evidence base for current treatment of carotid artery disease. The AHA Stroke Council recommended surgical revascularization in symptomatic (prior symptoms of a nondisabling stroke or TIA) patients with more than 70% carotid stenosis, provided the perioperative risk of stroke and death is less than 6%. In patients with more than 60% stenosis without prior symptoms (asymptomatic group), the recommendation for revascularization is valid provided the perioperative risk of stroke and death is less than 3% and the patient has a life expectancy of at least 5 years.

To minimize potential confounding variables, such as conditions known to increase the risk of operative treatment, patients in the NASCET and ACAS studies were carefully selected, and those who were regarded as high surgical (CEA) risk were excluded. Box 32-5 lists anatomical characteristics and comorbidities that were used to define high CEA risk. In the NASCET study, contralateral occlusion was not excluded, and 30-day risk of stroke and death in this cohort was 9.4% (≈︀2.2 times the risk without this problem).6 Excluding the SAPPHIRE study (see below), surgical outcomes in high–CEA risk patients have never been tested in a large multicenter prospective trial with independent neurological assessment and event adjudication, rendering conclusions about benefit of the procedure in this population less clear.

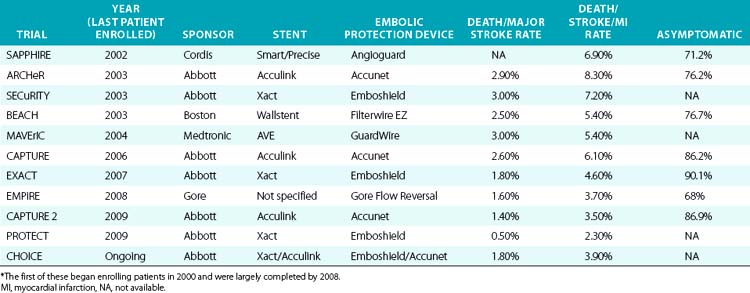

During the initial investigation of CAS with embolic protection as a therapeutic alternative to CEA, the target population included patients who were high risk for CEA. These clinical trials were designed using a nonrandomized registry format. Since the FDA considers each carotid stent and embolic protection system as a unique device set, each with its own risk profile, as a condition of marketing (PMA) approval, every manufacturer was required to perform its own separate study. This regulatory requirement explains why so many “CEA high-risk registries”73,99–103 were formed, all of which enrolled the same target population (Table 32-5). The study design, study hypothesis, and statistical approach were largely similar for all the registries. The goal was to determine whether outcomes in high-risk surgical patients treated with the particular sponsor’s stent in conjunction with its EPD was less than or equal to that of objective performance criteria (OPC) derived from historical controls undergoing surgical intervention with CEA. An OPC of 15% for patients with comorbidities and 11% for patients with anatomical risk factors was negotiated a priori and agreed to by the FDA.

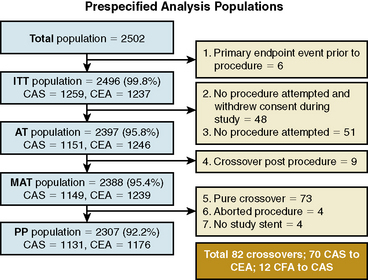

The SAPPHIRE101 study was the only one that included a randomized arm (CAS vs. stent). This multicenter noninferiority randomized study was conducted in 29 centers across the United States, and results were published in 2004.101 The study enrolled symptomatic patients (≥50% stenosis on duplex ultrasound, 29% of the patient population) and asymptomatic patients (≥80% stenosis on duplex ultrasound), and the primary endpoint was defined as the cumulative incidence of death, stroke, and MI within 30 days of treatment, or death and ipsilateral stroke between day 31 and 1 year from the time of the procedure. Although the inclusion criteria included high–CEA risk patients, prior to randomization, all members of the investigative team (neurologist, vascular or neurosurgeon, and interventionalist) had to agree that the patient was a suitable candidate for either endarterectomy or stenting. If the surgeon assessing the patient concluded that endarterectomy could not be safely performed, but the interventional physician judged that stenting was feasible, the patient was not randomized, but instead was entered into a stent registry (n = 406). Likewise, if the surgeon deemed the patient suitable for surgery, but the interventional physician did not think stenting was feasible, the patient was entered into a surgical registry (n = 7).

By intention-to-treat analysis, the primary endpoint at 1 year occurred in 20 CAS patients (12.2%) and 32 CEA patients (20.1%); P = 0.05. Cranial nerve injuries were seen in 5% of the patients undergoing CEA. The investigators concluded that carotid stenting with embolic protection was not inferior to CEA in a high surgical risk population. The durability of carotid stenting in this patient group (durability refers to the procedure’s ability to prevent stroke, not the need for repeat intervention due to restenosis) has been supported by the 3-year follow-up data, which demonstrated that there was no significant difference in long-term outcomes between patients who underwent CAS using an EPD and those who underwent endarterectomy.104

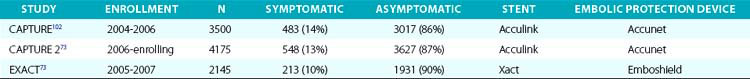

Post-approval Registries

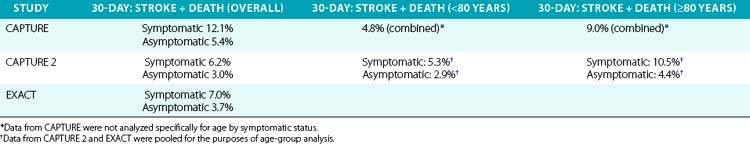

As part of the condition for marketing approval of its devices (stents and EPDs), the sponsor, Abbott Vascular, agreed to perform FDA-mandated post-approval studies to assess the occurrence of rare and unanticipated device-related events. These post-approval studies have also provided an opportunity to assess the outcomes of carotid stenting in high–CEA risk patients in the non-trial setting (real world). In 2009, Gray et al.73 reported the outcomes of two such prospective multicenter (280 U.S. sites, 672 operators) post-market surveillance studies involving CAS with distal embolic protection using filters in high–CEA risk patients. These studies had pre- and postprocedure neurological evaluation and independent adjudication of neurological events. Results of these two studies, as well as the outcomes of an earlier large (n = 4225) post-approval study (CAPTURE),102 are summarized in Table 32-6.

In summary, key outcomes from the CAPTURE 2 and EXACT data sets73 are:

• 30-day death and stroke: 6.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.8%-8.4%) in the combined symptomatic population and 3.2% (95% CI, 2.8%-3.7%) for the combined asymptomatic population.

• 30-day death and major stroke: 1.5% (95% CI, 1.2%-1.8%) for the combined population and 2.6% (95% CI, 1.6%-4.0%) and 1.3% (95% CI, 1.0%-1.6%) for the combined symptomatic and asymptomatic groups, respectively.

• In subjects with anatomical features unfavorable for surgery, independent of age:

• In the cohort of patients identified with physiological factors unfavorable for surgery, the combined 30-day rate of death and stroke for 574 symptomatic patients was 6.4% (95% CI, 4.6%-8.8%), and for the 4603 asymptomatic patients was 3.3% (95% CI, 2.8%-3.9%).

Operator Experience

In a recent publication, the CAPTURE 2 study investigators105 analyzed the carotid stenting outcomes of 3388 patients (representing 64% of the total number of patients) to determine whether physician or site-related variables affected outcomes of CAS. Symptomatic patients and patients older than 80 years of age (two known predictors of adverse outcomes) were excluded. During a 3-year interval between March 2006 and January 2009, 459 operators treated the study population in 180 U.S. hospitals. The composite rates of death, stroke, and MI, and the composite rates of death and stroke at 30 days were 3.5% and 3.3%, respectively, for the full CAPTURE 2 study cohort and 2.9% and 2.7%, respectively, for the asymptomatic nonoctogenarian subgroup.

Two thirds of the sites (118 of 180 [66%]) had no death or stroke events. Within the remaining sites, an inverse relationship between adverse event rates and hospital patient volume as well as individual operator volume was observed. The death and stroke rates trended lower for interventional cardiologists compared with other specialties. Similar conclusions were drawn from a German registry analysis106 and a recent meta-analysis of published studies.107 The CAPTURE 2 study authors concluded that both site and operator volume were the most important determinants of perioperative events, and defined a threshold of 72 cases for consistently achieving a 30-day death and stroke rate of less than 3%. This 72 case number is higher than the entry threshold for operators participating in randomized trials like CREST or ACT I (Carotid Stenting vs. Surgery of Severe Carotid Artery Disease and Stroke Prevention in Asymptomatic Patients) trials.

Analysis and Critique

With the exception of SAPPHIRE, all other studies dealing with carotid stenting in high–CEA risk patients were registry studies. Despite the registry label, it should be noted that the high-risk CAS registries were performed under FDA-scrutinized clinical protocols, with prospective data collection and event adjudication. The importance of prospective independent clinical review was demonstrated by Rothwell and Warlow108 investigating adverse event rates following CEA. They found a threefold difference in neurological events between operator self-reported and independent neurologist-assessed events. Both NASCET and ACAS used such prospective independent evaluations.

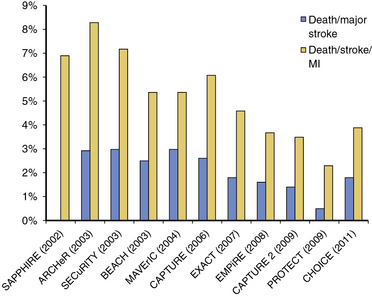

Carotid stenting outcomes have shown a steady and continuous improvement since the initial introduction of these devices in U.S. trials (Fig. 32-19). For example, compared with outcomes in the ARCHeR and the original CAPTURE registries, the combined results of the CAPTURE 2 and EXACT studies showed improvement (30-day death and stroke: 6.9% vs. 5.7% vs. 3.6%, respectively), and these improved outcomes meet AHA guidelines in the younger than 80 years age group. As will be discussed later, in the CREST study, the majority of neurological events were minor strokes, with substantial if not complete resolution of the neurological deficits during the follow-up period.

Figure 32-19 Published adverse event rates for carotid artery stent studies and registries over the past 10 years.

The higher event rates in the early (pre-2005) high risk CEA carotid stent registries (i.e., event rates that breached the AHA thresholds) is one likely explanation for lack of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reimbursement for asymptomatic patients undergoing carotid stenting, despite FDA approval for this indication in 2004. The outcomes of the CAPTURE 2 and the EXACT post-marketing registries are compelling because at least in the non-octogenarian high–CEA risk population, both symptomatic and asymptomatic (Table 32-7), the death and stroke outcomes were within the AHA guidelines.

Carotid Stenting in Symptomatic Standard-Risk Patients

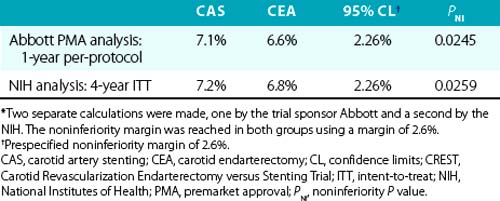

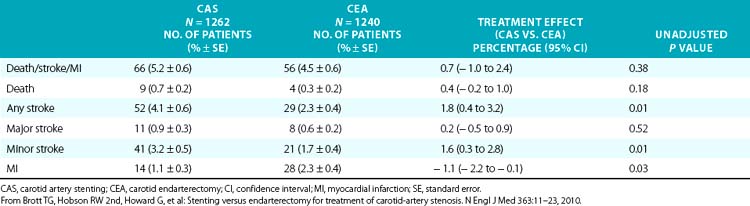

The introduction of CAS into clinical practice as an alternative to CEA has required the completion of randomized trials to evaluate its efficacy and safety. In patients with symptomatic carotid disease, there are four completed large, multicenter randomized controlled trials. These include the Endarterectomy versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3 S) trial,41 the Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy (SPACE) trial,40 the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS),109 and CREST.39 Since the CREST study also included asymptomatic patients, it is discussed separately. Although the results from these individual trials remain a source of controversy, the results are broadly similar and have enabled the publication of guidelines by national societies.

EVA-3 S,41 a non-inferiority study, was conducted in 30 centers across France and recruited and randomized usual (standard-risk) CEA patients. These patients were within 120 days of either a TIA or non-disabling stroke and had an ICA stenosis of 60% or greater in the index (symptomatic) carotid artery. Stenosis severity was verified by catheter angiography or duplex ultrasound and MRA. The primary endpoint was any stroke or death within 30 days of treatment. Although the enrollment target was 872 patients, the trial was stopped prematurely by the data safety monitoring board (DSMB) after 527 patients had been enrolled for reasons of safety and futility. The primary endpoint was seen in 9.6% of patients in the stenting group, compared to 3.9% in those undergoing endarterectomy (P = 0.01). Later analyses demonstrated that the difference between the two groups persisted out to 4 years.110

SPACE40 was a multicenter (n = 35) multinational (German, Austrian, and Swiss participation) non-inferiority study. This trial recruited and randomized standard–CEA risk patients within 180 days of either a TIA or moderate stroke (Rankin score <4). Patients had a stenosis severity of 70% or greater (ECST criteria; ≥50% NASCET) in the index carotid artery. Stenosis severity was determined by catheter angiography or duplex ultrasound. The primary endpoint was ipsilateral stroke and death within 30 days of treatment. The trial was stopped after data from 1183 patients had been analyzed, which led to the conclusion that a larger sample size (almost 2500 patients) would be needed; however, further funding was not available. Event rates were 6.84% in the stenting group, compared with 6.34% in patients undergoing endarterectomy. Although the outcome rates were similar between the two groups, the trial failed to demonstrate the noninferiority of CAS (i.e., the study failed to prove that outcomes in patients undergoing stenting were no worse than outcomes of CEA).