14 Caring for the patient undergoing endocrine therapy

Introduction

In Chapter 2, we discussed how some cancer cells grow in the presence of hormones (chemical messengers). Using this knowledge, endocrine or hormone therapy is a way of manipulating a patient’s hormones to reduce the growth of a cancer or prevent it from growing back.

Read Waugh and Grant (2010) (see References) or a similar textbook and make a list of the tissues/organs that are under the control of hormones. What is the role of these hormones and how might they influence cancer growth?

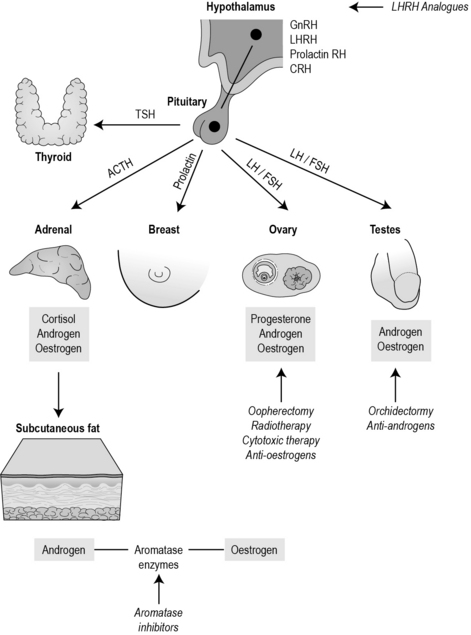

To give an example, the hypothamus produces luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), which in turn stimulates the pituitary to release luteinising hormone, which stimulates the ovary to produce oestrogen which then triggers ovulation. Figure 14.1 identifies the hormone pathways particularly significant in cancer.

How endocrine treatments work

Cancers that arise from organs normally under hormonal control may be treated by endocrine therapy, namely breast, prostate, thyroid and endometrial cancers. Endocrine therapy either blocks hormones, increases hormones or inhibits the conversion of hormones. Generally, these treatments are not curative, but are useful neoadjuvantly, adjuvantly, palliatively and possibly as a preventative measure. Sometimes endocrine therapy is used as a sole treatment, where other treatments such as surgery are not recommended or a patient wishes to undergo a less invasive treatment. One of the reasons why endocrine therapy does not get rid of cancer completely is because as the cancer mutates, the cells look and behave differently to one another. Often some of the cells will be responsive to endocrine treatment, while others will not be. Sometimes a cancer will respond initially, but may become less responsive as the cancer mutates further. As stated in Chapter 2, at diagnosis a patient is tested to see if the cancer is sensitive to hormones. Sixty-five per cent of women with breast cancer will be oestrogen positive – these tend to be older women and they are more likely to have a better prognosis.

Remember that oestrogen is not only produced by the ovaries but also by the adipose tissues. After the menopause, a woman will continue to produce oestrogen because aromatase enzymes convert androgens into oestrogen. To stop this, the aromatase inhibitors (such as anastrozole) bind with the enzyme and stop the conversion. These drugs are now recommended by NICE (2006) for postmenopausal women with primary breast disease.

Table 14.1 summarises the main endocrine therapies

| Type of cancer | Type of endocrine therapy | Examples of agents |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer (pre- and postmenopausal) | Selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) | Tamoxifen, droloxifene, idoxifene, raloxifene |

| Breast cancer (postmenopausal) | Aromatase inhibitors | Anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane |

| Breast cancer (postmenopausal) | Selective oestrogen receptor downregulator | Fulvestrant |

| Breast cancer (premenopausal) | LHRH analogues | Goserelin (Zoladex) |

| Endometrial cancer Prostate cancer (rarely) |

Additive hormonal therapies | Megestrol acetate (Megace) and medroxyprogesterone (Provera) |

| Prostate cancer | LHRH analogues | Goserelin (Zoladex) |

| Prostate cancer | Anti-androgens | Steroidal: cyproterone acetate (Cyprostat) Non-steroidal: (flutamide TDS, nilutamide, bicalutamide/casodex) |

| Prostate cancer | Oestrogens | Stilboestrol |

Side effects

• Weight gain (commonly weight increase around abdomen and more likely if combined with chemotherapy (Goodwin et al 1999)).

• Vaginal bleeding and discharge.

• Thromboembolic disease (deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE)).

• Modest increased risk of endometrial cancer.

• Joint stiffness and bone pain; hair thinning mild/moderate.

• Bone mineral density disturbance and increased plasma lipids with the aromatase inhibitors.

Identify a patient undergoing endocrine therapy. Ask what side effects they have experienced. Then look up the drug. What are the common side effects caused by this drug specifically? Does the patient’s experience reflect the expected side effects? How are the patient’s physical functioning, psychological and social status affected? If you do not encounter a patient receving endocrine therapy while on placement, look up a few of the drugs identified in Table 14.1. Make a few notes on how the drug is administered and what the common side effects are. This information can be useful to help you prepare for patient care.

Men often experience erectile dysfunction and develop female physical characteristics such as higher pitched voice, breast enlargement and hot sweats. This can be quite distressing and can influence an individual’s sexuality and body image.

Watch the following clip ‘Hampered by Hormones’ from The Prostate Cancer Charity :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5YMhAvwOWr0 (accessed November 2011).

Visit The Prostate Cancer Charity Website and read the Living with Hormone Therapy booklet:

http://www.prostate-cancer.org.uk/media/41582/htbooklet.pdf (accessed November 2011).

Goodwin P.J., Ennis M., Pritchard K.I., et al. Adjuvant treatment and onset of menopause predict weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:120–129.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Breast cancer (early) – hormonal treatments: guidance. London: NICE; 2006.

Waugh A., Grant A. Ross and Wilson anatomy and physiology in health and illness. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Ervik B., Nordoy T., Asplund K. Hit by waves: living with local advanced or localized prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy or under active surveillance. Cancer Nursing. 2010;33(5):382–389.

Fenlon D. Hormone therapy. In: Kearney N., Richardson A. Nursing patients with cancer: principles and practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Fenlon D.. Endocrine therapies. Corner J., Bailey C. Cancer nursing: care in context, 2nd ed., Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

Pennery E. The role of endocrine therapies in reducing risk of recurrence in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(3):233–243.

Souhami R., Tobias J. Cancer and its management, 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2005.

Yarbro C.H., Hansen Frogge M., Godman M. Cancer symptom management. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2004.

Yarbro C.H., Hansen Frogge M., Godman M. Cancer nursing: principles and practice, 6th ed. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2005.

Breast Cancer Care patient information, http://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/breast-cancer-breast-health/treatment-side-effects/hormone-therapy/ (accessed May 2011).

The Prostate Cancer Charity patient information, http://www.prostate-cancer.org.uk/info/prostate_cancer/treatment_hormones.asp (accessed May 2011).