10 Caring for the patient undergoing cytotoxic therapy

Introduction

Recall the cell cycle in Chapter 2. Re-read this and determine which normal cells in the body are rapidly and continually dividing. Think about what specific impact this might have on the patient undergoing cytotoxic therapy.

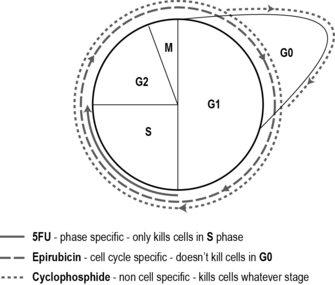

There are hundreds of cytotoxic drugs, grouped together according to their biochemical nature (Table 10.1). We also classify the drugs in terms of how they act on the cell. Most cytotoxic drugs disrupt the cell cycle by damaging the DNA or affect mitosis and are classified into groups depending on which part of the cell cycle they affect:

• Cell cycle non-specific drugs kill cells whether in the cycle or resting, i.e. all phases: G0, G1, G2, S and M phases.

• Cell cycle non-phase-specific drugs only kill cells that are active in the cell cycle, i.e. G1, G2, S and M phases, but not G0.

• Cell cycle phase-specific drugs kill cells that are in a particular phase of the cell cycle, i.e. only cells in G1 phase.

| Groups of cytotoxics | Examples of drugs |

|---|---|

| Antimiotic antibiotics | Doxorubicin Epirubicin |

| Anthracyclines | Mitomycin C |

| Non-anthracyclines | Methotrexate 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) Vinca alkaloids Capecitabine |

| Antimetabolites | Vincristine |

| Alkylating agents | Cyclophosphamide |

| Taxanes | Taxotere Taxol |

Most cytotoxic drugs are given in combination – usually two or three drugs are used within a regimen. This enhances the effect of the drugs by killing more cells and minimising the range of side effects as well as lessening the risk of cancer cells becoming resistant. For instance, one cell cycle non-specific drug, one cell cycle non-phase-specific and one cell cycle phase-specific drug may be used. Each of the three drugs has different side effects which means the patient is able to tolerate a high dose and a greater tumour kill may be achieved if the drugs all have different modes of action. As an example, the most commonly used chemotherapy regimen for breast cancer after surgery is 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC) (see Fig. 10.1). Sometimes a single drug is used to manage or reduce a patient’s symptoms.

Preparing the patient for cytotoxic treatment

Routes of administration

Watch the peripheral cannulation video at:

http://cancernursing.org/forums/topic.asp?TopicID=74 (accessed November 2011).

Another common method of giving cytotoxic drugs is orally. The number of drugs given this way is increasing due to pharmaceutical developments. It is clearly an attractive method as the patient may receive treatment at home. However, it does result in less contact time from healthcare professionals which may lead to undiagnosed side effects and less psychological support (Irshad & Maisey 2010). There is the issue of concordance (compliance) – patients may not take the tablets as instructed, either forgetting a dose or taking too many. There is also the safety issue of storing medication in the home environment.

Side effects

Patients often see side effects as an inevitable part of receiving cytotoxic drugs and think that they must endure and tolerate them. As a result, some patients are reluctant to report side effects as they fear that treatment may be withdrawn, thus reducing the success. It is often difficult for patients to interpret the significance/severity of side effects and know when to seek advice. For instance, they might think that pins and needles might be due to a trapped nerve rather than a neurological toxicity of a cytotoxic (Table 10.2).

| Seconds/minutes | Allergic reactions, flushing, nausea, taste alteration |

| Days/weeks | Mucositis, nausea and vomiting (acute, delayed, anticipatory), alopecia, diarrhoea, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia |

| Months/years | Anaemia, neurological, organ toxicity (heart, lung, liver, kidney), secondary tumours |

Cytotoxic-induced nausea and vomiting

Cytotoxic drugs damage the rapidly dividing cells that line the gastrointestinal tract resulting in nausea and vomiting. In addition, the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) in the brain is stimulated, registering that there are toxic substances in the body. Cytotoxic-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is reported as one of the most distressing side effects of treatment (Bergkvist & Wengstrom 2006), with approximately 50% of patients experiencing nausea and/or vomiting, resulting in significant distress (Molassiotis et al 2008).

Anticipatory nausea and vomiting is a distressing condition resulting from a psychological reaction to cytotoxic treatment. It usually develops over time and the patient associates a traumatic feeling with the hospital environment, a specific nurse or a cannula. This becomes overwhelming and is expressed as nausea and vomiting. Because this is caused by an emotional rather than a physiological reaction, it is not responsive to antiemetics. Instead, non-pharmacological therapy, such as hypnotherapy and visualisation techniques, may be helpful. Nausea and vomiting is explored further in Chapter 15.

Alopecia

Eighty-five per cent of hair follicles are actively in the cell cycle (this is why hair continually grows). Therefore, hair loss is a common side effect of cytotoxic treatment, especially when the drugs are cell cycle non-specific (killing more cells off in one go). It normally takes a month or two before the hair begins to come out in a noticeable amount, but after a couple of weeks the patient will find more hair in the plug hole after washing their hair and in the hairbrush. The more a patient styles or handles their hair, the quicker it will come out. Washing with a ‘frequent wash’ shampoo will help prolong the process, however eventually there will be complete loss. This is often extremely distressing for patients, affecting their body image and sexuality (Power & Condon 2008).

Scalp cooling is a way of trying to minimise hair loss by reducing the temperature of the scalp and restricting the blood flow to the hair follicles, thus reducing the amount of cytotoxic drug reaching the follicle and damaging the cell. There are several ways of cooling the scalp – the most common is using a cold cap that is filled with gel and then chilled. The cap fits closely to the scalp and is worn for half the time it takes for the body to get rid of the drug. In addition, the cap requires changing as it warms up. This means that scalp cooling can only be used for a small number of patients who are receiving cytotoxic therapy administered over a short period of time, with a short half-life. For example, with the FEC regimen (mentioned above), a normal treatment time is approximately 45 minutes in total. When using scalp cooling, the cannula is placed first and a cold cap is worn for 15 minutes. This is then replaced by another cap and treatment is commenced. After 45 minutes, the cap is replaced and worn for a further 45 minutes, a total of 1 hour and 45 minutes, more than doubling treatment time. Scalp cooling does not prevent hair loss – it is just a way of retaining some hair and often it is not successful. After treatment, hair will return but this may take a number of months. Also, the hair may return a different colour or texture (Van den Hurk et al 2010).

Neutropenia

Neutropenia, sometimes known as immunosupression, is the most life-threatening side effect of receiving cytotoxic treatment. As well as causing direct mortality, neutropenia may delay treatment, reducing the overall efficacy of cytotoxics (Methven 2010). Neutropenia-related infections result in additional hospital admissions and impact on patients’ quality of life.

Individuals with a cancer diagnosis are at high risk of infection not only due to the effects of cytotoxic drugs, but also to the number of invasive procedures they undergo. Many medications they receive, such as steroids, increase the risk. As discussed in Section 1, cancer generally occurs in older individuals. As we get older, our immune system is less effective and there is increased likelihood of other co-morbidity, such as diabetes. This will increase the risk of infection.

Re-read your lecture notes or an anatomy and physiology textbook (such as to refresh your knowledge of the body’s immune response to infection. Read Coughlan and Healey (2008) (see References for details) for more information about caring for patients with neutropenia.

Make a list of factors that may influence the risk of infection in cancer patients.

When a patient is neutropenic, many endogenous pathogens living in the patient’s body (normally not doing any harm) are able to use the opportunity of the reduced immune system to cause damage (Vento & Cainelli 2003). A good example of this is the herpes simplex virus, otherwise known as a cold sore. We may never know how or when we became infected by the virus, but as soon as we are feeling run down or are getting over an illness, the virus can activate and develop in a lesion, usually on the lip. Another example is the varicella zoster virus, otherwise known as chickenpox. A patient may have had chickenpox as a small child – although they recover from the spots and fever, the virus remains in the body in a dormant state in the nerve tissues. It reactivates when the immune system is low or working especially hard; this is known as shingles. Shingles can be extremely painful and cause respiratory damage. In an immunosuppressed patient, it may be fatal.

Patients undergoing cytotoxic treatment should avoid taking paracetamol (Coughlan & Healey 2008). This is because having a temperature or pyrexia helps the body to mount an immune response to fight the pathogen in the body. A temperature acts as a signal to the immune system/white blood cells to go to the site of infection and kill the invader. Paracetamol artificially reduces body temperature by ‘resetting’ the hypothalamus (like a thermostat). This indicates to the immune system there isn’t a problem. When the temperature is within the normal range, the patient or healthcare professional may think that there is no longer a problem and not respond. If the cause of the infection is not treated then the patient may become septic and go into shock and may suffer a cardiac arrest. Therefore, it is vital that the early signs and symptoms of infection are detected and prompt action is taken.

Mucositis

Because the mucosa (lining of the oral cavity) is continually renewing itself, it is very sensitive to cytotoxic drugs. Approximately 40% of patients undergoing cytotoxic therapy will develop mucositis, sometimes known as stomatitis (Raber-Durlacher et al 2010). This can affect a patient’s nutritional status, communication and body image, and may cause pain. Treatment may be halted or postponed, particularly if the mucositis is severe. The effect can be minimised by regular teeth cleaning after each meal. No special mouth washes are required (Van Achterberg 2007). Ice chips help reduce the chance of mucositis, by reducing the blood supply and slowing the cell cycle of the cells lining the mouth (Nikoletti et al 2005, Worthington et al 2006).

Bergkvist K., Wengstrom Y. Symptom experiences during chemotherapy treatment – with focus on nausea and vomiting. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2006;10:21–29.

Brown M. Nursing care of patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Nursing Standard. 2010;25(11):47–56.

Coughlan M., Healey C. Nursing care, education and support for patients with neutropenia. Nursing Standard. 2008;22(46):35–41.

Irshad S., Maisey N. Considerations when choosing oral chemotherapy: identifying and responding to patient need. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl.). 2010;19:5–11.

Methven C. Effects of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia on quality of life. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2010;9(1):30–33.

Molassiotis A., Stricker C.T., Easby B., et al. Understanding the concept of chemotherapy related nausea: the patient experience. European Journal of Cancer. 2008;17:444–453.

Nikoletti S., Hyde S., Shaw T., et al. Comparison of plain ice and flavoured ice for preventing oral mucositis associated with 5FU. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(6):750–753.

Power S., Condon C. Chemotherapy-induced alopecia: a phenomenological study. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2008;7(7):44–47.

Raber-Durlacher J.E., Elad S., Barasch A. Oral mucositis. Oral Oncology. 2010;46(6):452–456.

Van Achterberg T. The effectiveness of commonly used mouthwashes for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: a systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl.). 2007;15(5):431–439.

Van den Hurk C.J., Mols F., Vingerhoets A.J., Breed W.P. Impact of alopecia and scalp cooling on the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):701–709.

Vento S., Cainelli F. Infections in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: aetiology, prevention and treatment. Lancet. 2003;4(10):595–604.

Worthington H.V., Clarkson J.E., Bryan G., et al. Interventions for preventing oral mucositis for patients with cancer receiving treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000978.pub5.

Baquiran D.C., Gallagher J. Cancer chemotherapy handbook, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001.

Brighton D., Wood M. The Royal Marsden Hospital handbook of cancer chemotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

Coward M., Coley H.M. Chemotherapy. In: Kearney N., Richardson A. Nursing patients with cancer: principles and practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Dougherty, L., Bailey, C., Chemotherapy. In: Corner, J., Bailey, C. (Eds.), Cancer nursing: care in context, 2nd ed. Blackwell, Oxford

Duffy L. Care of immunocompromised patients in hospital. Nursing Standard. 2009;23(36):35–41.

Maxwell C.J. Putting evidence into practice: evidence-based interventions for the management of oral mucositis. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(1):141–152.

Prescher-Hughes D.S., Alkhoudairy C.J. Clinical practice protocols in oncology nursing. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2007.

Yarbro C.H., Hansen Frogge M., Godman M. Cancer symptom management. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2004.

Yarbro C.H., Hansen Frogge M., Godman M. Cancer nursing: principles and practice, 6th ed. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2005.

European Oncology Nursing Society, http://www.cancernurse.eu/ (accessed May 2011).

Cancer Nursing education, videos and other learning materials, http://www.cancernursing.org/ (accessed May 2011).

Cancernausea.com Website (USA), http://www.cancernausea.com/.

Chemotherapy information, http://www.chemotherapy.com/ (accessed May 2011).

Charity Website with information and help with alopecia and wigs: http://www.mynewhair.org/Home.aspx (accessed May 2011).

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, http://www.nice.org.uk/ (accessed May 2011).

NHS Choices, http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Chemotherapy/Pages/Definition.aspx (accessed May 2011).

Oncology Nursing Society (UK), http://www.ukons.org/ (accessed May 2011).

Oncology Nursing Society (USA), http://www.ons.org/ (accessed May 2011).

Royal College of Radiologists chemotherapy guidelines, http://www.rcr.ac.uk/ (accessed May 2011).