Chapter 27

Caring for Patients in a Culturally Diverse Society

What the scalpel is to the surgeon, words are to the clinician. … [T]he conversation between doctor and patient is the heart of the practice of medicine.

Philip A. Tumulty, MD (1912–1989)

The cultural aspects of physical diagnosis and medicine are becoming increasingly important. By the middle of the twenty-first century, the majority of the population in the United States will no longer be white. It is imperative that all health care professionals understand the dimensions and complexities of caring for individuals of culturally diverse backgrounds in the United States. Equally important is the provider’s knowledge of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that affect the patient’s access to and use of health care resources. When treating recent immigrants, clinicians must be aware that their attitudes toward illness and treatment may be very different from those of the indigenous population. Second-generation immigrants may have yet a different appreciation.

The United States is home to one of the most ethnically and culturally heterogeneous populations in the world. There are more than 100 ethnic groups and 400 tribes of Native Americans in the United States, each with diverse practices and beliefs. This chapter provides some relevant issues of cultural diversity in health care and is intended to sensitize the health care provider to the effect of cultural diversity on health care delivery. This chapter is not comprehensive because not all groups are represented; however, no culture was intentionally omitted. The chapter is divided into two main sections: (1) a discussion of some general considerations in delivery of health care in a multicultural society and (2) selected cross-cultural perspectives.

The names used to identify various groups change with time. Within a cultural group, there are variations as to how its members identify themselves and what name they prefer. The names of cultural groups often grow out of ethnic and ideologic movements.

The examples of health care practices in this chapter illustrate traditional cultural differences. However, not all patients of a certain group hold that group’s traditional beliefs. Many patients who are now second- or third-generation Americans may not follow these practices at all but may know of them from parents or grandparents. Caution should also be taken to avoid stereotyping the patient by race, lifestyle, cultural or religious backgrounds, economic status, or level of education; this is detrimental to establishing a solid doctor-patient relationship. The health care provider must recognize that there is also great variability within cultures.

This chapter is intended not to stereotype or label any particular group but rather to teach the health care provider how to recognize common cultural characteristics to better understand the needs of his or her patients. Cultural competence is the understanding of the behaviors, policies, skills, health-related beliefs, communication patterns, and attitudes of our culturally diverse society to lessen the gap between the health care provider and the patient.

General Considerations

According to the 2010 census, 308.7 million people resided in the United States on April 1, 2010—an increase of 27.3 million people, or 9.7%, between 2000 and 2010. The vast majority of the growth in the total population came from increases in those who reported their race or races as something other than white alone and those who reported their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino.

The definition of race categories for the 2010 Census was as follows:

More than half of the growth in the total population of the United States between 2000 and 2010 was due to the increase in the Hispanic population. In 2010, there were 50.5 million Hispanics in the United States, composing 16% of the total population. Between 2000 and 2010, the Hispanic population grew by 43%—rising from 35.3 million in 2000, when this group made up 13% of the total population. The Hispanic population increased by 15.2 million between 2000 and 2010, accounting for more than half of the 27.3 million increase in the total population of the United States.

The non-Hispanic population grew at a relatively slower pace during the decade, at approximately 5%. Within the non-Hispanic population, the number of people who reported their race as white alone grew even more slowly between 2000 and 2010 (1%). Although the non-Hispanic White alone population increased numerically from 194.6 million to 196.8 million during the 10-year period, its proportion of the total population declined from 69% to 64%.

The black or African-American alone population was 38.9 million and represented 13% of the total population. There were 2.9 million respondents who indicated American Indian and Alaska Native alone (0.9%). Approximately 14.7 million (approximately 5% of all respondents) identified their race as Asian alone. The smallest major race group was Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone (0.5 million) and represented 0.2% of the total population.

The remainder of respondents who reported only one race—19.1 million (6% of all respondents)—were classified as “some other race” alone.

Although the Black alone population had the third-largest numeric increase in population size over the decade (4.3 million), behind the White alone and Asian alone populations, it grew more slowly than most other major race groups. In fact, the black alone population exhibited the smallest percentage growth outside of the white alone population, increasing 12% between 2000 and 2010.

Of the 308.7 million people, 223.6 million (72%) were white, 38.9 million (13%) were African American or black, 14.7 million (5%) were Asian, 2.9 million (0.9%) were Native Americans (American Indian, Inuit and Inupiat, and Aleut), 500,000 (0.2%) were Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders.

Language can be a significant barrier to good health care. According to the 2000 census, there are more than 15 million people in the United States who have “limited English proficiency.”1

More than 5% of the populations of California, New York, Texas, New Mexico, and Hawaii have limited English-language skills.

Race, Culture, and Ethnicity

Race, as defined by Merriam-Webster‘s Collegiate Dictionary, tenth edition, is a “class or kind of people unified by community of interests, habits, or inherited physical characteristics.” The term culture has a broad meaning; it refers to the unifying beliefs of any group of people of similar religion, values, attitudes, ritual practices, family structure, language, or mode of social organization. Culture provides values that are shared by members of a specific society or a social group within a society. Culture socializes its members on how to perceive the world, how to behave in the world, and how to experience the world emotionally. Elements that represent cultural values and notions include language, social or familial roles, and beliefs about the universe, the nature of good and evil, appropriate dress, eating and hygienic habits, manners, and food. Culture pervades lives and shapes human identity. All personal experiences and norms are perceived through the culture from which they emerge. It shapes human perception of reality and influences societal forms of conduct. Different cultures reinforce different behaviors; what is acceptable in one culture may be considered deviant in another.

Cultural values determine, in part, how a patient should behave. This includes the types of acceptable treatment, type of follow-up permitted, and who will make the decisions. From the medical point of view prevalent in the United States, the clinician and the patient make the decisions, but when a patient’s family exerts great influence, the situation can be very different. In some traditional cultures, the family takes over this role for the patient. Authority figures such as parents or grandparents often predominate. For example, in the case of Romany (“Gypsy”) patients, the primary decision-maker may not even be a relative. Among Orthodox Jewish patients, a medical decision may be made only after consultation with a rabbi. Among the Amish, the entire community may play a role in the decision-making.

Ethnicity is a cultural group’s sense of identification associated with the group’s common social and cultural heritage. The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups defines ethnicity as “a common geographical origin, language, religious faith, and cultural ties (e.g., shared traditions, values, symbols, literature, music, and food preferences).”

Disease, Illness, and Health

The terms disease and illness are often used interchangeably. Medical sociologists and cultural anthropologists, however, make a distinction. The word disease refers to a disorder in which there is a change from normal in the body’s structure or function, involving one or more organs of the body. Illness is the subjective distress felt by the patient and by those close to the patient, rather than the actual state of ill health. The patient’s culture often determines how the patient interprets, explains, responds to, and deals with a disease. It also influences when a patient will seek health care decisions and from whom. Members of some cultures try to “normalize” their symptoms, maintaining that symptoms in a certain age group are not abnormal. Affected members might say that they have experienced the symptoms before and that therefore the symptoms are normal for them. Other cultures dictate immediate care even if symptoms are minimal. According to some cultures, to be ill is a punishment or curse, whereas according to others, to be ill is to be weak, irresponsible, or unmasculine. For many patients in the United States, the clinician is only one of many health care providers and often not the first. Some patients are likely to consult a healer from their own culture before seeking consultation from a Western-trained clinician. Two patients from different cultures may react differently to the same disease or symptoms. Thus, treating illness, rather than treating disease, requires the health care provider to have not only a broad understanding of medicine but also an understanding of the patient’s cultural background.

Health, as defined by Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th edition, is “the condition of being sound in body, mind, and spirit.” It is often defined more abstractly as the “absence of disease.” In some cultures, health is viewed as the freedom from evil. Other cultures regard health as day and illness as night. By extrapolation, health reflects light and clean, and illness reflects dark and dirty. These depictions form the basis of the beliefs of many cultures, which are discussed later in this chapter.

Culture and Health

It is crucial for any health care provider to have an appreciation for cross-cultural family values, language, norms, religion, and political ideology. An estimated 80% to 90% of all self-recognized episodes of illness are managed exclusively outside a formal health care system. Traditional healers, mediums, self-help groups, and religious practitioners provide a substantial proportion of this health care.

Within the United States, there are many culturally distinct groups. Even within these groups, there are many variables such as educational achievement, socioeconomic class, generational status, and political relationship between the country of origin and the United States. All these factors contribute to establishing the dynamic reality of an ethnic group. Being in a low socioeconomic bracket appears to be a strong predictor that ethnicity will influence the behavior of such patients, regardless of whether they are newly arrived or native born. The following factors are other predictors of behavioral ethnicity:

• Frequent return visits to the native area

• Immigration to the United States at an older age

• A major difference in dress or diet from the surrounding population

Newly arrived immigrants often experience prejudice; the toll on their psyche may be a heavy one. But cultural change is not limited merely to immigration. Moving around in the same country or changing professions may also result in culture shock. The new culture may be viewed as unempathetic, cruel, and critical. The newcomer may experience frustration, irritability, fatigue, loss of flexibility, and an inability to communicate feelings to others. Distrust, paranoid tendencies, depression, anxiety, and physical and psychosomatic illnesses may develop. It is therefore necessary to include a patient’s and family’s immigrational and migrational history in the evaluation of the patient because the family is the carrier of ethnic traits and identity.

Cross-cultural marriages can offer the best and worst of both worlds. The reconciliation of different norms and traditions may provide an enriching experience, but a clash of different cultural traits may lead to strained relations among spouses and families.

The influence of ethnicity and culture on health and health-belief practices has long been recognized as a result of the presence of racially related diseases and syndromes, as well as societal predispositions to illness. It is very important to inquire about patients’ perceptions of their symptoms and illness. To understand better the cultural influences on a patients’ medical problem, Lipkin and colleagues (1995) suggested several questions for eliciting patients’ explanations for their symptoms or health-belief practices:

“What do you call your problem?”

“Why do you think it started when it did?”

“How does it work? What is going on in your body?”

“What kind of treatment do you think would be best for this problem?”

“How has this problem affected your life?”

“What frightens or concerns you most about this problem and treatment?”

The answers to these questions provide insight into the hopes, aspirations, and fears of the patient.

Genetic Diseases

The simultaneous manifestation of two or more forms or alleles of a gene in a population is a genetic polymorphism. Certain genetic polymorphic states, such as blood groups, are strongly associated with disease. As early as 1953, an association of blood group A with gastric carcinoma was recognized. The causal relationship of hemoglobin S to sickle cell anemia is well known.

There are many genetic diseases. Some very common ones are described here.

Middle Easterners, both Arab and non-Arab, are among the populations most affected by genetic disease. The common cultural practice of consanguinity accounts for as many as 25% to 60% of marriages in some countries and has led to epidemic levels of genetic disease. Beta thalassemia is one of the most common genetic diseases in the Middle East. More than 16 million people are unsuspecting carriers for this serious blood disorder, which causes a lifetime of chronic illness, suffering, and an early death. It is characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis that leads to severe anemia, fever, hyperuricemia, and skeletal deformities. The association of these disorders with Mediterranean background has been long established. The human leukocyte antigen gene complex and the many diseases associated with it continue to receive attention. Table 27-1 summarizes some specific diseases on the basis of geographic distribution and ethnic populations.

Table 27–1

Geographic and Ethnic Distributions of Specific Diseases

| Specific Disease | Highest Incidence |

| Cancer of the skin | Eastern Australia |

| Cancer of the cheek | Southern India, New Guinea |

| Cancer of the nasopharynx | Southeast Asia, Kenya |

| Cancer of the esophagus | Northern France (Brittany) |

| South Africa | |

| Eastern Zimbabwe | |

| Western Kenya | |

| East of the Caspian Sea | |

| Cancer of the stomach | Japan |

| Korea | |

| Eastern Finland | |

| Mountain region of Colombia | |

| Eastern Zaire | |

| Southwest Uganda | |

| Cancer of the colon | North America |

| Western Europe | |

| Cancer of the liver | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | Africa (10 degrees north and south of equator) |

| Appendicitis | North America |

| South America | |

| Europe | |

| Diverticular disease | North America |

| Western Europe | |

| Australia | |

| New Zealand | |

| Hemorrhoids | North America |

| South America | |

| Europe | |

| Cholelithiasis | Southwestern United States |

| Sweden | |

| Stenosing duodenal ulcer | Southern India |

| Eastern Zaire | |

| Ischemic heart disease | North America |

| South America | |

| Europe | |

| Finland | |

| Hypertension | Japan |

| Taiwan | |

| Venous thrombosis | North America |

| South America | |

| Europe | |

| Diabetes | North America |

| Urinary bladder stones | North America |

| South America | |

| Europe | |

| Multiple sclerosis | Rural Thailand |

| Rosacea | Northern United States |

| Northern Europe | |

| Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome | Great Britain, especially Scotland |

| Takayasu’s disease | Japan |

| Italy | |

| Lactase deficiency | Japan |

| Choroideremia | Greece |

| Jewish people | |

| African Americans | |

| Thailand | |

| Eskimos | |

| Japan | |

| Abetalipoproteinemia | Northern Finland |

| Glycosphingolipidoses Gaucher’s disease Niemann-Pick disease Tay-Sachs disease |

Ashkenazi Jews |

| Familial Mediterranean fever | Ashkenazi Jews |

| Sephardic Jews | |

| Armenians |

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an inherited condition that causes episodic attacks of fever and painful inflammation of the abdomen, chest, and joints. People with FMF may also develop a rash during these attacks. The attacks last for 1 to 3 days and can vary in severity. Between attacks, the person typically feels normal. These symptom-free periods can last for days or even years. FMF is most common among ethnic groups from the Mediterranean region, notably people of Armenian, Arab, Turkish, Iraqi Jewish, and North African Jewish ancestry. One in every 200 to 1000 people in these groups is affected by the disease, and carrier rates in some populations have been estimated as high as 1 in 5. Cases of FMF have also been found in other populations, including Italians, Greeks, Spaniards, Cypriots, and less commonly, Northern Europeans and Japanese.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic condition characterized by the production of abnormally thick, sticky mucus, particularly in the lungs and digestive system. CF is a chronic condition that worsens over time.

According to the National Institutes of Health, CF is the most common deadly inherited condition among white people in the United States. Disease-causing mutations in the CFTR gene are more common in some ethnic populations than others:

| Ethnic Group | Carrier Rate | Affected Rate |

| French Canadian | 1 in 16 | 1 in 900 |

| Caucasian | 1 in 28 | 1 in 3000 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 in 28 | 1 in 3000 |

| Hispanic | 1 in 46 | 1 in 8300 |

| African American | 1 in 66 | 1 in 17,000 |

| Asian | 1 in 87 | 1 in 30,000 |

Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency, or phenylketonuria, is a treatable inherited disease in which the body cannot properly process the amino acid phenylalanine because of a deficient enzyme called phenylalanine hydroxylase. If severe forms of the disease go untreated, the buildup of phenylalanine can be toxic to the brain, causing impaired development and leading to severe and irreversible mental disability. If treated early and consistently, however, people with phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency can lead completely normal lives.

Since the mid-1960s, it has been standard for hospitals in North America to screen newborns for phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency using a drop of blood obtained from a heel prick. This is now a routine practice in most developed countries.

The frequency of carriers and affected individuals in select populations is listed here.

| Ethnic Group | Carrier Rate | Affected Rate |

| Turkish | 1 in 26 | 1 in 2600 |

| Irish | 1 in 33 | 1 in 4500 |

| Caucasian American | 1 in 50 | 1 in 10,000 |

| East Asian | 1 in 51 | 1 in 10,000 |

| Finnish | 1 in 200 | 1 in 160,000 |

| Japanese | 1 in 200 | 1 in 160,000 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 1 in 225 | 1 in 200,000 |

Tay-Sachs disease is the most common and severe form of hexosaminidase A deficiency. Tay-Sachs disease is a progressive condition that results in the gradual loss of movement and mental function. It is typically fatal early in childhood. The symptoms of Tay-Sachs disease usually appear in infants between 3 and 6 months of age. Initially, infants lose the ability to turn over, sit, or crawl. They also become less attentive and develop an exaggerated startle response to loud noise. As the disease progresses and nerve cells further degenerate, infants with Tay-Sachs develop seizures, vision and hearing loss, mental disability, and eventually become paralyzed. Death usually occurs by the age of 4.

Tay-Sachs disease is most common among specific ethnic populations, particularly Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe, certain French-Canadian communities in Quebec, Amish populations in Pennsylvania, and Louisiana Cajuns. Tay-Sachs disease is found in people of all ethnicities, although the risk outside of the ethnic groups mentioned previously is much lower. Roughly 1 in 30 Ashkenazi Jews is a carrier of Tay-Sachs, compared with 1 in 300 for the non-Jewish Caucasian population. Since 1970, an organized campaign in the Jewish community to educate potential parents about Tay-Sachs and test them for mutations causing this disease has dramatically lowered the number of children affected by the disease. Because of these successful screening programs, today the majority of children born in the United States with Tay-Sachs disease do not have an Ashkenazi Jewish background.

Traditional Medical Beliefs

People interpret traditional medical beliefs about the body’s shape and size, inner structure, and functions in terms of their cultural background. To illustrate various cultural beliefs about body functions, consider that patients often ascribe their symptoms to blood that is “too thin,” “too thick,” “too little,” or “too slow.” Blood can be used as an index of an emotional state (blushing); a personality type (“cold-blooded” or “hot-blooded”); a kinship (“blood is thicker than water”); a diet (“thin blood”); or a social relationship (“bad blood between people”). “Bad blood” is also frequently used to refer to syphilis.

As another example of the cultural beliefs about blood, consider views about menstruation. A study in 1977 by Snow and Johnson evaluated the views of inner-city women in a public clinic in Michigan. Many of the 40 women interviewed felt that menstruation was a method of ridding the body of impurities that could cause illness or poison the body. Many of these women believed that when the uterus was “open” during menstrual flow, they were vulnerable to disease. They also believed that it was only at this time that a woman could become pregnant. At all other times in the menstrual cycle, the uterus was “closed,” and pregnancy was impossible. Another common fear among the women was that of impeded menstrual flow. They feared that stoppage might cause a backup of poison and hence a stroke, cancer, or sterility. This fear may be a reason why these women avoid the use of certain methods of contraception, such as intrauterine devices and diaphragms.

Another belief about menstruation was studied by Skultans (1970) in two groups of women from a small mining village in South Wales in the United Kingdom. One group of women felt that menstruation was a process by which the body “cleansed” itself; the longer the period or greater the blood loss, the better. These women regarded menstruation as normal and essential to a healthy life. In contrast, another group of women from the same mining town viewed menstruation as damaging to their overall health; they feared that the blood loss was threatening to their health and welcomed the thought of menopause.

Finally, Ngubane (1977) described the beliefs of South African Zulu women about menstruation. They felt that menstruating women had a “contagious pollution” that was deleterious to other living creatures and to the natural world. A man’s virility would be reduced if he had sexual relations with a menstruating woman. Crops would be ruined and cattle would die if menstrual blood came in contact with them. In some of these African communities, menstruating women are isolated from the community because of their “dangerous pollution.”

Although food is a source of nutrition, it plays many roles and is deeply embedded in almost all aspects of everyday life. Some foods eaten in one society are forbidden in others. Each culture has its own rules of food preparation and of how it is served and how it should be eaten. Every culture defines foods that are edible and those that are not. In France, frog legs and snails are delicacies, whereas in the nearby United Kingdom, they are rarely eaten. Some foods are considered sacred and others are prohibited. Food abstentions occur during the Jewish fast of Yom Kippur and the Muslim fast of Ramadan. Orthodox Hindus are forbidden to kill or eat any animal, especially the cow. However, milk or milk products may be consumed because they do not require the death of the animal. Orthodox followers of Islam and Judaism are prohibited from eating pork products. Only the meat from mammals that chew their cud and that have cloven hoofs is edible, provided that the animal was slaughtered ritually: according to halal (Islam) or kosher (Jewish) law. Kosher law dictates that meat and milk products are never eaten together. In Sikhism, pork is allowed, but never beef. Rastafarians are generally vegetarians, and alcohol is strictly forbidden.

Some cultural groups in the Islamic world, the Indian subcontinent, Latin America, and China believe in the “hot-cold theory” of disease. This belief, which is intuitive and common throughout Latin America, states that the body is regulated by hot and cold “humors.” The belief stems from Hippocratic humoral theories brought to this hemisphere in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by the Spanish and Portuguese. Health is the balance of these hot and cold body fluids. Illness is defined by a humoral imbalance of these forces. All mental states, illnesses, and natural and supernatural forces are grouped into hot and cold categories. Foods, herbs, and medications are also classified as hot or cold and serve to restore the body to its natural balance. Although it may seem that the system is based on temperature, the thermal state in which the foods or medications are taken is not important. Certain types of herbal tea, served hot, are considered cold, whereas cold beer, because of its alcoholic content, is considered hot. In the hot-cold theory of disease, conditions that are hot, such as ulcer disease, constipation, pregnancy, diarrhea, and rashes, should be balanced and treated with cold foods, such as coconut, avocado, sugar cane, and lima beans. Menstruating or postpartum women who believe in the hot-cold theory may avoid certain “cold” vegetables and fruits because these fruits are liable to clot their “hot” menstrual blood, impeding its flow, making it flow backward into the body and thus causing nervousness or insanity. Cold illnesses, such as arthritis or joint pains, are treated with hot therapy, such as aspirin, iron tablets, penicillin, chili peppers, chocolate, evaporated milk, onions, garlic, or cinnamon.

Consider the following. A patient may be on diuretic therapy and require potassium supplementation. The clinician may advise the patient to eat foods high in potassium, such as oranges or bananas. If the patient acquires an upper respiratory infection, which is a cold disease, he or she may stop eating these fruits, which are classified as cold, because eating them will only worsen the imbalance. This belief should be recognized because it contributes significantly to whether a patient does or does not adhere to therapy. Problems can arise when a clinician prescribes a “hot” medication for a “hot” disease or a “cold” medication for a “cold” disease. The hot-cold theory is even more complex in that the assignment of the “hot” or “cold” qualities varies from culture to culture. It is often difficult for the health care provider to remember the various hot-cold combinations. If a Hispanic/Latino patient has these beliefs, the clinician should ask Hispanic/Latino colleagues on the medical team or the patient and family directly about these combinations. Inquiring respectfully about the patient’s culture can be effective in enhancing doctor-patient relationships. To achieve maximum therapeutic benefits for patients who believe in the hot-cold theory of disease, the health care provider is advised to work within its framework, if possible, in prescribing medicines and diet. He or she should try to consult medical colleagues, nurses, and social workers who share the patient’s background.

Belief in witchcraft as a cause of illness is widespread. In the Hispanic/Latino population, terms such as mal puesto, mal de ojo, mal artificial, brujería, hechicería, and enfermedad endañada are used to describe the “illness of damage”: someone has done something to cause injury, illness, or death. Mal de ojo, or evil eye, is believed to result from excessive respect or love from another person, especially toward newborn children. A recurring theme in witchcraft belief is that animals are present in the body and are introduced by magical means. Almost always, the offending animal is a reptile, insect, or amphibian. These animals have been dried and pulverized, sprinkled onto food, and reconstituted in the body of the victim. Symptoms are often described as animals crawling over the body or wriggling throughout the intestines. The belief is that this is a magical expression of friends, relatives, or strangers wishing bad luck to come to an individual. A hex is an evil spell, a misfortune, or a case of bad luck that one person can impose on another. Magical oils, incenses, religious items, and candles may be used to repel the evil. In the Hispanic/Latino community, a botánica, or religious artifact shop, sells many of these items. The shopkeeper serves as a consultant on health and related issues. Figures E27-1 and E27-2, taken in the Otto Chicas Rendon Botánica on 116th Street in New York City, depict examples of such shops. Often, the entrance to a botánica, as shown in Figure E27-1, shows predominant Roman Catholic imagery. Candles, flowers, plants, and bowls of coconut and molasses frequently surround the Christian statues. The influence of Christianity, as well as of the African and Arabic cultures, is apparent in the idols shown in Figure E27-2. As of mid-2012, there were more than 900 botánicas listed in the business telephone books in the United States, of which there were more than 95 in Manhattan. There are probably many more that are not listed.

Figure E27–2 Idols in a botánica.

Very often, patients who believe they are victims of witchcraft do not seek medical attention from a clinician. Certain members of their community may be consulted to chant special prayers and incantations to cure the illness. At other times, they may require exorcism or some other dramatic therapy to drive the illness out of the body. Other common “cures” include turpentine, kerosene, mothballs, and carbon tetrachloride.

Culture and Response to Pain

The sociocultural variations in physical pain expression are important to recognize. Pain is a complex phenomenon for both the patient and the health care provider, influenced as much by personal values and cultural traditions as by physiologic injury and disease. Multiple factors influence the perception and expression of pain. Pain is an important form of biofeedback and is essential, as a warning signal, for survival. The experience of physical pain, however, has three components: (1) a person’s sensation of pain, (2) a person’s tolerance for pain, and (3) a person’s expression of pain. Health care providers must rely on the pain sufferer to describe the symptom of pain, the sum of these three components. The last of the three is culturally mediated.

Some studies have indicated that there may be cultural variations in the tolerance for pain as well. In some cultures, the complaints of pain are rewarded with increased attention and comforting behavior. Individuals of Hispanic/Latino background or from the Middle East or Mediterranean areas commonly voice their pain with great emotion. Some believe that they must openly express their pain; if they do not, they may aggravate their illness. In contrast, Southeast Asian, Asian-Indian, Japanese, and Native American patients believe that emotional control is extremely important. Their cultures encourage stoicism; these people rarely openly express or even indicate the presence of pain, unless it is extremely severe. In many instances, the ability to withstand great pain is a sign of manhood, reliability, and moral uprightness.

The anthropologist Zborowski (1952) studied pain in four groups of male patients in a veterans’ hospital. Third-generation Americans generally expressed pain with little emotional behavior and became withdrawn from their friends. Italian and Jewish men were very expressive and preferred to be with others while in pain. Irish men endured pain as a private event and neither sought any medication for it nor wanted to socialize with others. These generalizations about cultural responses to pain must be used cautiously and not become the basis of stereotyping.

It is also important for the health care provider to recognize that many patients from Southeast Asian and Native American cultures frequently express their illness through altered states of consciousness such as trances and hallucinations. The clinician who is unaware of this type of presentation may incorrectly diagnose it as some form of psychosis.

Ethnicity and Pharmacotherapy

It is increasingly recognized that there are ethnic differences in the response to pharmacologic agents. For example, in psychopharmacology, new research has begun to provide insight concerning the biologic mechanisms that underlie this differential response. Data have been accumulated about the ethnic differences in drug metabolism, as well as the plasma proteins that bind psychotropic agents. Several ethnic differences in drug metabolism appear to be related to different genetic forms in the drug-metabolizing cytochrome P-450 enzyme system. It has been demonstrated that a high percentage of Asians and African Americans have an enzyme form that metabolizes drugs at a much slower rate; in individuals with this form, potentially toxic blood levels of drugs may develop after administration of standard doses of certain psychotropic agents. Some Chinese herbs, such as ginseng and muscone, have been shown to have potent stimulating effects on cytochrome enzymes; other herbs substantially inhibit the activities of these enzymes. It is therefore important to determine the serum levels of drugs in a patient in whom an atypical response has developed. Other studies have shown that Asian and Hispanic/Latino patients with schizophrenia require lower doses of neuroleptic agents, such as chlorpromazine, than do white patients. Asian patients are also more likely to exhibit the extrapyramidal side effects of the neuroleptic agents than are white patients.

Cross-Cultural Differences in Morbidity and Mortality Rates

It is important to be aware of the considerable cultural diversity in patterns of morbidity and mortality rates in the United States. Some patterns may be purely genetic, as in Tay-Sachs disease among persons of Ashkenazi Jewish (Eastern European) descent or sickle cell anemia among African Americans. The pattern of health for African Americans is very different from that of their white counterparts. The average life expectancy for African Americans is 69.6 years of age, in comparison with 75.9 years of age for white persons. This may in part be related to a higher infant mortality rate among African Americans. The incidence of hypertension and its consequences is much higher in African Americans than in white persons. African-American men die from cerebrovascular accidents at almost twice the rate of white men. In addition, death from coronary artery disease in African-American women is more common than in white women. Diabetes is 35% more common among African Americans than among the white population. Many African Americans, like members of other ethnic groups, have had negative experiences with the Western medical system. The perception of a judgmental or impersonal attitude in a white health care provider may contribute to a fear or distrust of the traditional health care system. As a result of this lack of trust, many African-American patients seek alternative medical treatment.

People of Hispanic/Latino descent (e.g., Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans) are the fastest-growing minority in the United States. Many are at increased risk for alcoholism, cirrhosis, hypertension, specific cancers, and tuberculosis. The incidences of diabetes and cancers of the gallbladder, liver, pancreas, cervix, and stomach are higher among Hispanic/Latino people than in the general population. Cervical and stomach cancers occur more than twice as often in Hispanic/Latino people as among non-Hispanic/Latino whites. There is also an increased incidence of acute promyelocytic leukemia in the Hispanic/Latino population. Within this group, the Puerto Ricans have the poorest health. This may be related to the fact that many older patients do not trust conventional medicine or health care providers, or that migrant people are often forced to live in areas of crowding and poor sanitation.

The rate of tuberculosis among Chinese Americans is higher than in the general population. In fact, the incidence of tuberculosis is more than 40 times higher among Southeast Asians than among the non-Asian population. Both first- and second-generation Chinese Americans have a greater incidence of coronary artery disease than do Asian Chinese, presumably because of differences in diet and stress in the United States. The Japanese and Koreans have the highest incidence of gastric cancer, presumably related to diet and their high consumption of salt. The incidence of liver cancer is more than 12 times higher among the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans than within the non-Asian population. Hepatitis B is also more common in Southeast Asians.

Native Americans have one of the highest morbidity and mortality rates; their death rate is 30% higher than that of the general population in the United States. This risk may be linked to the fact that Native Americans are one of the most disadvantaged ethnic groups in the United States. They have a high incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. In addition, the incidence of congenital adrenal hyperplasia is greater in Native Americans than in the white population.

Traditional Healing Systems

Traditional, or folk, healers still play a large role in medicine in industrialized societies. Each culture has its own healers: spiritual healers, mediums, herbalists, shamans, fire doctors, medicine men, astrologists, occult healers, bone setters, lay midwives, and leg lengtheners are only a few. Meditation, prayer, massage, exercise, relaxation techniques, acupuncture, acupressure, hypnosis, imagery, therapeutic touch, martial arts, and herbs are important therapeutic modalities of many of these healers. Spiritual healing is widespread. Christian Science healing, started in 1879 in Boston, teaches that those who follow Jesus must follow him in healing, which is done through the mind.

The Hispanic/Latino groups call their traditional healers by different names, such as the Mexican-American curanderos (male) or curanderas (female) and parteras, Puerto Rican espiritistas, and Cuban santeros. The Haitian voodoo healers, Inuit and African shamans,2 Hawaiian kahunas, and Navaho singers are also important folk healers for their ethnic groups. It is crucial for the health care provider to respect patients who follow these practices and to encourage them to express their need for these providers without shame or fear. The health care provider should discuss with the patients how to combine the help of these providers and medical therapy.

In addition to the natural healing traditions, there are many magical-religious traditions. As stated previously, religion plays a major role in one’s perception of illness. The “evil eye” is one of the oldest and most widespread of all superstitions. The nature of the evil eye is defined differently by different groups, but it is generally accepted that an evil eye causes a sudden injury or illness that may be prevented or cured by rituals or symbols. The afflicted person may or may not know the source of the evil eye. There are several traditional practices used in the protection of health; they include wearing objects, such as charms, that protect the wearer. Figure E27-3 is a photograph that was taken in a botánica; it shows eye bead charms that are worn on a string or chain around the neck, wrist, or waist to protect an individual. The blue eye bead is commonly worn by Greeks to ward off the evil eye. The mal occhio is worn by people of Italian descent; the mano milagroso by Mexicans; the mano negro by Puerto Rican babies; the hamsa, or Hand of God, by Jews; the ayn by the Arabic cultures; the Thunderbird by Hopi Indians; knotted hair or fragments of the Korean by people of South Asia; and red ribbons by Eastern European Jews. The Chinese wear jade to protect them from disease. When the green or red jade object discolors or turns brownish, it is replaced because it is assumed that the person has been exposed to an evil eye or other disease. Figure E27-4 shows several jade bracelets and charms. This photograph was taken in a Chinese jewelry shop in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Figure E27–3 Eye beads to protect from the “evil eye.”

Figure E27–4 Jade bracelets and charms.

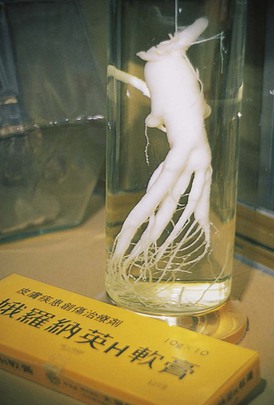

Various traditional cultures use food substances to protect health. Many people eat raw garlic or onions or wear them around their necks to prevent disease. Members of Greek, Italian, and Native American ethnic groups may hang onion and garlic in their homes for protection. Chicken soup, a Jewish remedy, has long been thought to protect health and speed recovery. Nervo forza is a Guatemalan vitamin tonic commonly used in Central America. Traditional Chinese eat “1000-year-old” eggs to prevent illness. The most famous of all Chinese herbs is ginseng (Panax schinseng), which is derived from the root of a plant resembling a human figure. A typical ginseng root appears in Figure E27-5. Ginseng has been revered for thousands of years as a general panacea. Known as an “adaptogen,” ginseng has many medicinal purposes; it naturally “adapts” the vital functions of the human system to compensate for adverse conditions such as stress, malnutrition, and the deterioration associated with aging. Ginseng is a slightly bitter root that is used to promote secretion of bodily fluids, and it is recommended by Chinese health practitioners to treat more than 25 medical problems. It is commonly used for anemia, indigestion, impotence, and depression, as well as for replenishing energy and improving sleep. By “building the blood” and stimulating vital organ energies, it is intended to balance the yin and yang (described later in this chapter) throughout the body. Ginseng must be prepared in earthenware and not in metal because metal destroys its healing properties. Ginseng is contraindicated in patients with excess heat. A bowl of ginseng roots and other ginseng preparations are shown in Figure E27-6.

Figure E27–5 Ginseng root.

Figure E27–6 Bowl of ginseng roots and other ginseng products.

Finally, many religious objects are worn to protect individuals from disease. The Virgin of Guadalupe is the patron saint of Mexico. It is believed that she protects people and their homes from the evil eye. Her image is pictured on medallions. In the Roman Catholic tradition, there are many saints who are patrons of specific illnesses. People may wear medals with the name and image of the saint on them to prevent the development of a problem. Figure E27-7 shows holy cards with the pictures of saints. These pictures are used to cure and protect individuals from disease. Gris-gris are symbols of voodoo; they may take a variety of forms and be used either to protect or harm a person.

Figure E27–7 Holy cards.

Specific Cross-Cultural Perspectives

In this section, some cross-cultural perspectives, including some common beliefs regarding health and illness, are examined. This section also discusses some strategies that can be applied to improving care of patients. The intention is to sensitize the reader to the vast differences among the major ethnic groups in the United States. It is beyond the scope of this book to include all ethnic groups; the reader is referred to the bibliography for this chapter, which can be found on the Student Consult site.

A note about socioeconomic status: Any patient in a low socioeconomic bracket is concerned with maintaining dignity and autonomy, and this should never be compromised in the eyes of the clinician. In addition, a respectful attitude is necessary in attaining a patient’s confidence and trust. Patients who are poor may fear that they may not be treated respectfully. Addressing the patient by the appropriate title, such as Dr., Miss, Ms., Mr., or Mrs. is important.

African Americans

African Americans constitute a heterogeneous ethnic group, and therefore it is impossible to make generalizations because there is no prototypical African-American patient. They live in all areas of the United States and are represented in every socioeconomic group, with a disproportionate number living in poverty. As a result, in many inner-city populations, lack of access to quality health care has particular deleterious consequences. One alarming result is that many preventable diseases often progress to life-threatening stages. Some diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension, are highly prevalent among African Americans. Consequently, when examining an African-American patient, regardless of socioeconomic status, the clinician should screen for these diseases and educate both the patient and the patient’s family. Because of media stereotyping, African Americans may react negatively to a general screening for human immunodeficiency virus or substance abuse. Clinicians need to approach this with sensitivity and reserve this testing for the segment of the African-American community that is at risk.

In Africa, illness has traditionally been attributed to several causes, primarily to demons and evil spirits. Beliefs regarding the role of spirits in causing disease may persist.

It is particularly important to investigate dietary patterns in the African-American patient. Certain ethnic foods, such as rice, plantain, yams, and okra, have deep cultural roots and should not be eliminated from the diet, if possible. Other ethnic foods, such as collards and turnips that are often heavily seasoned with salt and cured meat, may pose a health problem. Without the salt, these foods are wholesome parts of a diet. The eating of Argo starch has a historical basis because slaves ate clay and dirt, having been taught that these were rich in iron and other minerals. Some African Americans even today consume Argo starch as a substitute for clay and a source of minerals.

As culture defines health and illness, it also defines acceptable health care and treatment practices. All cultures offer home remedies as part of self-care. For some African Americans, the following is a partial list of home remedies:

• Poultices to fight infection

• Hot lemon tea with honey for colds

• Hot toddies for colds and congestion

• Raw onions placed on the feet in cases of fever

• The white membrane from a raw egg placed over a boil to bring it to a head

• Hot camphorated oil and mustard plaster on the chest for chest congestion

• Garlic placed on an ill person or in the person’s room to remove evil spirits

Hispanic/Latino People

The fastest-growing minority group in the United States comprises the Spanish-speaking peoples from various parts of the western hemisphere: Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico and other Central American countries, and South America. The Latinos residing in the United States are one of the youngest of the ethnic groups. Demographers have predicted, on the basis of the Latinos’ young age, their high fertility rate, and their migratory patterns, that by 2020 they will become the largest ethnic group in the United States, accounting for nearly 45% of the population. Although bonded by a common language and grouped together by their Spanish surnames, the Latino group has great heterogeneity and diversity in its many different traditions. Although Spanish has no dialects, many words may carry different meanings for various Latino groups, depending on their community of origin. The prevention of illness is a common practice frequently accomplished with praying, keeping relics in the home, and wearing religious amulets or medals. Figure E27-8 shows some religious amulets; Figure E27-9 shows a variety of rosaries and good-luck beads hanging in the foreground and magical oils and elixirs in the background. These photographs were taken in a botánica in New York City.

Figure E27–8 Religious amulets.

Figure E27–9 Beads, rosaries, and magic oils.

Latinos, like other traditional groups, are known for having a close-knit family unit, la familia. Latino families have strong ties and have maintained many of the qualities of the extended family system. They may have a great fear of being hospitalized and thus being separated from their families. Those who speak only Spanish are concerned that they will not be able to communicate with the medical personnel when help is needed. They have a sense of obligation toward each other and are expected to be responsible for all members of the family. It is not uncommon for a 90-year-old patient who speaks no English to be accompanied to the hospital by his or her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and even great-great-grandchildren. Decision-making is likewise a family matter. Never pressure the patient into making a decision; allow the patient time to discuss an issue with his or her family.

It is common for first- and second-generation Hispanic/Latino U.S. residents, as for many other immigrant groups, to regard health care institutions with a certain amount of distrust. When caring for a Hispanic/Latino patient, the clinician must consider the family as well. Some Hispanic/Latino people (more often older people, recent immigrants, and the less educated) still believe in curanderos or curanderas, espiritistas, or santeros, who are the holistic, family folk practitioners and spiritual counselors. These spiritualists believe that illness is caused by an intentional act of God, supernatural forces, or the ill will of others, and they emphasize healing through religious or medical ceremonies, potions, and amulets. They use a variety of yerbas (herbs, especially teas), charms, massages, and magical rituals. Limpias, or cleansing, is performed by passing an unbroken egg or selected herbs tied together over the body of the ill person. These healers do not advertise but are well known throughout their individual communities and play an important role in Hispanic/Latino health care. A yerberia or botánica is a community resource for purchasing traditional remedies and charms. Figure E27-10 shows containers with dried exotic herbs and teas. Again, the Christian and Arabic influences are evident.

Figure E27–10 Dried exotic herbs and teas in a botánica.

Patients are often fearful of discussing these health care practices with clinicians. For this reason, when they feel trusting enough to do so, it is important that the health care provider receive this information in a respectful manner. Try to work with the belief. Because many herbal remedies are pharmacologically active, it may be necessary to ask the patient not to consume them simultaneously with pharmaceuticals. There is usually a close, personal relationship between the patient and the healer. By using medical knowledge and adapting it to the patient’s beliefs, you can gain the patient’s confidence and encourage cooperation.

Candles play an important role in traditional healing. The votive candles are for specific deities or saints or for specific requests, such as money, love, health, and success. The candles are lit, and prayers are recited. Figure E27-11 shows some of the candles for sale in a botánica.

Figure E27–11 Votive candles.

Two important values in the Latino culture are respeto and dignidad. Respeto is demonstrated to a Hispanic/Latino patient when the health care provider dresses in the traditional garb of the profession expected by the Latino patient and communicates an interest in his or her life and health. Hispanic/Latino people also enjoy a brief social conversation before a discussion of their illness. This helps to develop a sense of confianza, or trust.

The belief in Santería originated more than 400 years ago in Cuba out of traditions of the African Yoruba people from Nigeria and Benin. These people were transported to Cuba to work as slaves on sugar plantations. From Cuba, this religious cult spread to the neighboring islands and to the United States; it arrived in New York in the late 1940s. Santería blends elements of West African beliefs with Roman Catholicism. Once a ghetto religion, Santería has a growing following among middle-class professionals, including white persons, African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans. The followers believe in one Supreme Being but also in African divinities known as orishas, each of which represents a human characteristic, such as power, or an aspect of nature, such as thunder. Each of these deities is worshiped in the image of a Catholic saint. There are several orishas related to health problems: the orisha Chango is linked to Saint Barbara,3 who is the god of thunder, lightning, and violent death; orisha Bacoso with Saint Christopher (infections); and orisha Ifa with Saint Anthony (fertility). Statues of saints or deities are commonly purchased for the home.

Figures E27-2 and E27-12 show some religious statues sold in a botánica. The believers pray to these idols to intervene with God to improve their lives and obtain blessings. Many of these idols are used for prayers for health. Notice the African elements blended with Catholicism in the idols. The seated figure with the red tie is Maximón, a Guatemalan believed to have powers for producing health, tranquility, protection, happiness, wealth, and improved sexual performance. The standing figure in the black suit to the right is the Venezuelan physician Dr. José Gregorio Hernandez Cisnero. He was known for his health-related miracles, and patients pray to him for health. The figure in the reddish-pink and gold robe with the crown is the famous statue of Baby Jesus of Prague, known in Spanish as El Niñito Jesus de Prague (also Atacha). Figure E27-13 shows the orisha Chango.

Figure E27–12 Religious Santería statues.

Figure E27–13 The orisha Chango on the left.

There is a very structured hierarchy in the practice of Santería. In charge is the babalow; next is the presidente, the head medium; and the third practitioner is the santero. The santero, an important, respected member of the Latino community, is said to possess the magical power of the orishas, known as ache. Ritual devotions involving African rhythms and dancing; offerings of food and animal sacrifice; divination with shells, bones, and eggs; trancelike states; and other rites are thought to reveal the sources of problems and to help in their resolution. During the ritual, the santero dresses in white robes with beaded necklaces and bracelets. Santería can be practiced in homes, parks, storefronts, or basements.

La partera or la comadrona is the traditional midwife or birth attendant in the Latino culture. These women are described as warm, caring, and cooperative. Their role is to give advice to pregnant women, to treat pregnant women for illnesses with herbs and massages, and to be in attendance during labor and delivery. The women offer both emotional and instrumental support during and after childbirth. Most parteras have birthing rooms in their homes.

There are several traditional, or culture-bound, illnesses of the Latinos. A culture-bound illness is one that is culturally defined. It may or may not have an equivalent from a Western medical perspective. Emotional trauma and strong emotions are recognized throughout Latin America as causes of illness. Conditions such as mal de ojo, empacho, ataque de nervios, susto, male aire, and caida de mollera are examples of Latino culture-bound syndromes.

Mal de ojo,4 or evil eye, is the result of dangerous imbalances in social relationships; illness is blamed on the “strong glance” of an envious person. Fever, sleeplessness, and headaches are common symptoms. Empacho, or upset stomach, occurs when a Latino patient is psychologically stressed during or immediately after eating. The main symptom is a feeling of a “ball in the stomach” associated with abdominal pain. Ataque de nervios is manifested by a sudden outburst of shouting or swearing, accompanied by a variety of symptoms that include dyspnea, chest tightness, memory loss, trembling, sense of heat, palpitations, dizziness, and paresthesias; it may be accompanied by, or caused by, hyperventilation. It is often seen when the patient is confronted with stressful life events, such as an accident, an acute severe illness, a funeral, or a death. During the episode, the person may fall to the ground with convulsions or lie motionless. An ataque de nervios may progress to susto, which is a prolonged condition that a patient experiences after having been exposed to a traumatic event. The patient is depressed, lacks interest in living, is withdrawn, and has a disruption of eating and hygienic habits. Susto, a nonkinetic fugue state, is a common stress reaction and may be described in part as a state of disorientation and confusion. Ritual prayers and herbal remedies are the common treatment. Mal aire, or bad air, is said to cause pain, facial twitching, and paralysis in children. Mothers are concerned that their young children will develop mal aire when exposed to cold air. It is therefore important to keep Latino children covered during an examination. Caida de mollera, or fallen fontanelle, affects infants; the fontanelle is displaced from its normal position at the top of the head. Diarrhea and restlessness are associated symptoms. It is important to reiterate that beliefs in folk healing cannot be generalized to all Latinos. These traditional beliefs vary from generation to generation and depend largely on the extent of assimilation into the mainstream culture.

Asian Americans

Asian Americans place much emphasis on obligation, authority, and honor. Those who have disgraced their families consequently suffer guilt. This guilt can be transformed into psychosomatic disease, which is common in this culture. Asian-American patients rarely complain of pain. They may suffer with it, but their complaints are few. If the health care provider suspects that a patient is having pain, it is fitting to ask whether pain is present. In general, after being asked, the patients acknowledge the pain. Older-generation Chinese individuals tend not to display emotions openly to strangers, nor do they usually accept any type of comforting physical contact, such as touching a shoulder or hand, as a form of empathy. In contrast to the Chinese or Japanese, in the Korean culture touching is common among men and women. In fact, it is far more common than in Western cultures.

Titles are important in communicating with the Japanese patient, as with other groups. The family name is usually written first. Bowing is very common and indicates respect; it is used when greeting and leaving. Avoiding eye contact, particularly with older Japanese patients, demonstrates respect. Another aspect of dealing with Japanese or Korean patients relates to the “yes-no” question and the infrequent use of the word “no.” Most older Japanese and Korean persons believe that to answer “no” puts an individual on the defensive. Therefore they may answer “yes,” meaning that they understand, not necessarily answering in the affirmative to the question. Nodding the head generally indicates attentiveness of the Japanese patient and not necessarily agreement. With some Japanese patients, as in other cultures, giggling is often a sign of embarrassment. Interviewers require patience and may need to proceed more slowly when questioning the Asian patient about intimate information, such as sexual behavior. It is generally best to avoid humor when interviewing a Japanese patient, especially an older patient.

Many Asian Americans believe in traditional medicine and distrust Western medicine. The “hot-cold” theory of disease is still accepted by some Asian Americans. Another example of the balancing of internal forces is seen in the Chinese belief in yin and yang. Everything in the world consists of both yin and yang forces. Yin is dark, female, and negative; yang is light, male, and positive. The key to good health is the balance between yin and yang; Chinese herbs and acupuncture help restore this balance. A common problem among Chinese patients is related to medication. According to traditional Chinese medicine, one dose of an herbal remedy usually “cures” an illness. Prescriptions of Western medications may require multiple doses over longer periods. Chinese patients may have difficulty in complying with this schedule. It is the clinician’s responsibility to explain carefully this difference in “medical” therapy.

Figure E27-14 is a picture taken in a traditional herbal pharmacy in San Francisco; it shows jars containing medicinal Chinese herbs. Deer antlers, mercury, turtle shells, bull testicles, snake meat, seahorses, and rhinoceros horns are other popular Chinese cures. The interviewer must respect the patient’s belief and, by attempting to understand it, is equipped to provide better care.

Figure E27–14 Medicinal Chinese herbs.

Many Chinese and Vietnamese persons, like other people, have an intense fear of being admitted to a Western hospital. This anxiety stems from the language barrier, inability to find a translator, fear of isolation from the family, different practices, and even food; many Southeast Asian persons are lactose intolerant. The health care provider must explain in detail the plan of treatment to the patient and the family members. If an interpreter is needed, the provider must ensure that the interpreter speaks the same dialect.

As in other traditional cultures, Asian Americans have several important culture-bound syndromes: hwa-byung, taijin kyofusho, hsieh-ping, amok, wagamama, shinkeishitsu, and koro. Hwa-byung is a common multiple somatic and psychological disorder, seen usually in married Korean women. Epigastric pain is the presenting symptom; it is feared that the pain will lead to death, and associated symptoms include insomnia, dyspnea, palpitations, and muscle aches. It often appears that anger is the precipitating cause. Taijin kyofusho is a syndrome in Japanese patients in which the patients complain that their body parts or functions are offensive to others. Hsieh-ping is a trancelike state in which Chinese patients believe themselves to be possessed by a dead relative or friend whom they have offended. Amok, which afflicts Malay men, is a sudden spree of violent attacks on people, animals, and objects. Wagamama, seen in Japanese patients, manifests with apathetic childish behavior with emotional outbursts. Shinkeishitsu is a form of severe anxiety and obsessional neurosis seen in young Japanese patients. Koro, a name of Malay origin, is a delusional condition seen in Southeast Asian and Chinese male patients; the patient suddenly grasps his penis, fearing that it will retract into his abdomen and ultimately cause his death. Family members are frequently called on to hold the penis. This disorder may continue for several days. The condition may be linked to another associated belief called “semen anxiety,” in which the patient feels that he has a deficiency of semen, which is believed to be a fatal condition.

Asian Indians

Asian Indians are people from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Although most Asian Indians speak English well, some idioms may produce confusion. The most common religious groups among Asian Indians are Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs. Hindus believe that life is a circle, continuous, without a beginning or end. There is also a strong belief in astrology. The Hindu family is a very strong unit, and health care decisions are commonly made by the senior members of the family. The cow is considered sacred; eating beef or veal, therefore, is strongly prohibited.

Muslims follow the teachings of Mohammed and Islam. The main principles of Islam are generosity, fairness, respect, cleanliness, and honesty. The consumption of alcohol, pork, and lard is strictly prohibited. Sex education and cremation are also commonly forbidden. Older Muslim patients may have a fatalistic attitude, which can interfere with compliance with medical therapy. Many Muslim women wear a veil over their head when in the presence of men outside the family and prefer female health care providers. In some cases, if a patient’s husband is present, a male clinician may be allowed to examine her.

Sikhism started in the fifteenth century in northern India. Sikhs believe in a single God and in reincarnation. Baptized Sikhs do not cut their hair and do not smoke or drink alcohol; many are vegetarians. A traditional Sikh greeting, similar to that of other Asian Indians, is with the palms of the hands pressed together in front of the chest. Women generally do not shake hands, and eye contact may be considered disrespectful.

The Asian-Indian population relies heavily on a wide-ranging pharmacopeia. Remedies can come from almost any natural substance. Ayurvedic medicine is an ancient Indian medical system; it teaches that imbalance in the body humors results in illness. Treatment is to restore the balance. Although Western medicine is recognized in India, it is estimated that there are nearly 4000 people for every Western-taught physician.

It is important for the clinician to recognize that taste and food are important parts of Asian-Indian beliefs. Each taste is believed to have special properties: sweet increases phlegm and appeases hunger and thirst; acid increases salivation and improves digestion; salt purifies the blood; pungent food provokes the appetite; bitter food also stimulates the appetite and clears the complexion. The study of medicines is more important than the study of illness; the traditional healer deals with symptoms and usually ignores the disease.

Native Americans

Native Americans constitute a heterogeneous group that comprises more than 400 federally recognized nations. American Indians, Aleuts, and Inuits (and Inupiats)5 are the largest groups of Native Americans. The traditional belief about health is that it reflects living in total harmony with nature and having the ability to survive under dire circumstances. People must treat their bodies with respect. Many Native Americans believe that there is a reason for every illness; illness is the price paid for something bad that has occurred or will occur. Several tribes associate illness with evil spirits. Illness may also result from breaking a taboo or the attack of a ghost or witch.

The traditional healer is the medicine man or woman. Often, the medicine man or woman uses meditation and crystal balls. On occasion, the medicine man or woman uses the root of jimsonweed to produce a trance to enable him or her to treat the patient better. The cause of illness is diagnosed by three types of divination: motion of the hand, star gazing, and listening. Chanting is a major part of the process. Many Native Americans also believe in witchcraft. Herbal remedies and an act of purification are major steps to curing illness.

Two important problems among Native Americans are alcohol abuse and domestic violence. Alcohol abuse is a critical health problem that is widespread and immeasurably costly to the Native American community. In historical, traditional Native American homes, alcohol abuse was not common. Currently, domestic violence is a major problem, and it is frequently related to alcohol abuse. The rate of suicide is also high among this population. In addition, there is a higher proportion of postnatal deaths among Native Americans, presumably because the women have inadequate prenatal care.

The Jewish People

Approximately 6 million Jewish people live in the United States. There are two large groups: the Ashkenazim, whose origins can be traced to Eastern or Northern Europe, and the Sephardim, whose origins are from the Mediterranean countries or the Iberian Peninsula. The majority of the Jews in the United States follow the Ashkenazi traditions. The Ashkenazim are linked linguistically through Yiddish, and the Sephardim are linked by Ladino, Spanish, Portuguese, French, or Arabic.

In the United States, there are three main divisions of the Jewish people, based on adherence to traditional practices and interpretation of Jewish law: Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. Although most Jews dress indistinguishably from others, many Orthodox individuals observe Jewish law by covering their heads with a skullcap called a yarmulke or kippah. Many married Orthodox women cover their heads with hats, wigs, or kerchiefs. Because of tradition, men and women are commonly separated in social situations. Another division of Jewish people is the Hasidim. This group broke off from mainstream Judaism in the seventeenth century to serve God without the necessity for immersion in religious study that was the standard in the Eastern European Jewish community at that time. Hasidim usually wear seventeenth-century–type black robes or suits with black hats. The men twirl their hair into ringlets at the sides of their face. Hasidim are generally passionate about their worship and adhere strictly to the biblical laws. These laws include restrictions regarding permissible foods (kosher laws, or Kashrut6) and forbidden foods (pork products or shellfish).

The Sabbath (Shabbat or Shabbos) is a strictly observed day of rest. When scheduling appointments, be aware of the Sabbath and do not schedule tests or clinic visits from Friday afternoon until after Saturday evening. Many religious Jews do not use anything electrical on the Sabbath. Therefore when visiting a religious Jewish person in the hospital, an interviewer may find that the rooms are dark because the patient and his or her family are not allowed to turn on the lights; the interviewer, however, may turn them on. Despite the many rules of Orthodox Judaism, health always comes first. Even on fasting days, pills may be taken, and ill and older persons, as well as children, are permitted to eat.

Many Jewish holidays are not marked on calendars. The health care provider should ask the patient about them when scheduling tests, to determine whether holidays will conflict with appointments. Many Jewish people may want to consult their rabbi before having a certain test performed or taking some form of medication. This should not be misconstrued as a mistrust of the health care provider; it is often culturally motivated.

There are several genetic conditions that appear more frequently in the Jewish population. These include Tay-Sachs disease (discussed earlier in this chapter), Gaucher’s disease, Bloom’s syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, FMF (discussed earlier in this chapter), Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia, pemphigus vulgaris, polycythemia vera, and Niemann-Pick disease.

When an Orthodox Jew dies, the body is never left alone from the time of death until burial; Orthodox friends and family pray around the body. The body is not embalmed, and the burial is usually within 24 hours. One exception to this rule is if the death occurs on a Friday evening (the Sabbath); the burial is then on Sunday. Autopsies usually are not allowed unless approved by the family’s rabbi.

The primary group targeted for annihilation in World War II was the Jewish people. Because of these experiences, Jewish patients, especially the older generation and older immigrants, may manifest greater discomfort, fear, and anxiety when confined in a hospital and when decisions are made about them. For more information, refer to the discussion of post-traumatic stress disorder in Chapter 2, The Patient’s Responses.

International Society for Krishna Consciousness

An important, small, originally Indian group in the United States is the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Its members believe in four rules of conduct: (1) no eating of meat, fish, or eggs; (2) no illicit sex; (3) no intoxicants; and (4) no gambling. They believe that the body is ruled by passion and the soul by serenity. The Krishna lifestyle is strictly regulated, and illness should never interfere with these activities. Followers seek medical assistance only when they are extremely ill.

Romanies

The tradition of the Romanies (or “Gypsies”) poses important health care problems. According to the Romany culture, the sources of all disease are demons, the evil eye, breaking taboos, and the fear of disease itself. Several Romany treatments involve transferring disease symbolically to another person or object. In general, Romanies turn to organized health care only during times of crisis. They do not hesitate to come to the hospital for serious illness; often, the extended family or entire tribe may accompany the patient. Preventive medicine and follow-up care are rarely used. Romany women are extremely reluctant to expose their bodies to male health care providers.

To protect their anonymity, Romanies are reluctant to identify themselves as such, often use assumed names, and may not provide truthful answers to non-Romany interviewers. Once a trusting relationship with a health care provider has been established, however, many Romanies feel more inclined to rely on that individual.

Concluding Thoughts

Health care professionals cannot be expected to know everything about each culture; rather, it is important that they know it is important to keep in mind cultural considerations in the treatment process and the doctor-patient relationship, often referred to as cultural humility. This chapter has introduced the health care provider to some aspects of several diverse cultures. Ideally, the clinician can be better prepared for the challenges of caring for patients in our culturally diverse society. Always be willing to listen to your patient and be flexible to your patient’s needs. The right approach for one patient may be the wrong approach for another. If your patient does not come back to you, you have not been a successful health care provider.

Bibliography

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report. [Available at] http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr10/nhdr10.pdf; March 2011 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Bigby JA. Cross-cultural medicine. American College of Physicians: Philadelphia; 2003.

Blackhall LJ, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA. 1995;274:820.

Boutin-Foster C, Foster JC, Konopasek L. Viewpoint: physician, know thyself: the professional culture of medicine as a framework for teaching cultural competence. Acad Med. 2008;83:106.

Brooks T. Pitfalls in communication with Hispanic and African-American patients: do translators help or harm? J Natl Med Assoc. 1992;84:941.

Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Western bioethics on the Navajo reservation: benefit or harm? JAMA. 1995;274:826.

Cohen MR, Doner K. The Chinese way to healing: many paths to wholeness. Perigee: New York; 1996.

Counsyl. Middle Easterners and genetic disease. [Available at] https://www.counsyl.com/learn/middle-eastern/ [Accessed January 2013] .

D’Avanzo CE. Barriers to health care of Vietnamese refugees. J Prof Nurs. 1992;8:245.

Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux: New York; 1997.

Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:229.

Galanti G. An introduction to cultural differences. West J Med. 2000;172:335.

Goston L. Informed consent, cultural sensitivity, and respect for persons. JAMA. 1995;274:844.

Grieco EM, Cassidy RC. Overview of race and Hispanic origin: census 2000 brief. C2KBR/01-1, Census 2000. U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC; 2001.

Haffner L. Translation is not enough. West J Med. 1992;157:255.

Herrera J, Lawson W. Cross-cultural issues in psychopharmacology. [editors] Mt Sinai J Med. 1996;63:283.

Kaptchuk TJ. The web that has no weaver: understanding Chinese medicine. Congdon & Weed: Chicago; 1983.

Kumas-Tan Z, et al. Measures of cultural competence: examining hidden assumptions. Acad Med. 2007;82:548.

Management Sciences for Health. The providers’ guide to quality and culture: what is cultural competence? [Available at] http://erc.msh.org/mainpage.cfm?file=2.1.htm&module=provider&language=English [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

McIvor RJ. Making the most of interpreters. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:268.

Mezzich JE, et al. Culture and psychiatric disorder: a DSM-IV perspective. American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC; 1996.

Morrison T, Conaway WA, Borden GA. Kiss, bow, or shake hands. Adams Media: Holbrook, Mass; 1994.

Murray RH, Rubel AJ. Physicians and healers: unwitting partners in health care. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:61.