16 Caring for patients at the end of life

Definition of end of life care

End of life care is often associated with the last days of life. This chapter takes a wider view and considers end of life care as the last ‘phase’ of life. The National Council of Palliative Care (NCPC) suggests ‘end of life care is simply acknowledged to be the provision of supportive and palliative care in response to the assessed needs of the patient and family during the last phase of life’ (NCPC 2006a:3).

The End of Life Care Strategy builds on this working definition from the NCPC by outlining six keys steps needed to be considered as part of the patient’s pathway (DH 2008:48):

1. Discussions as the end of life approaches.

2. Assessment, care planning and review.

3. Coordination of care for individual patients.

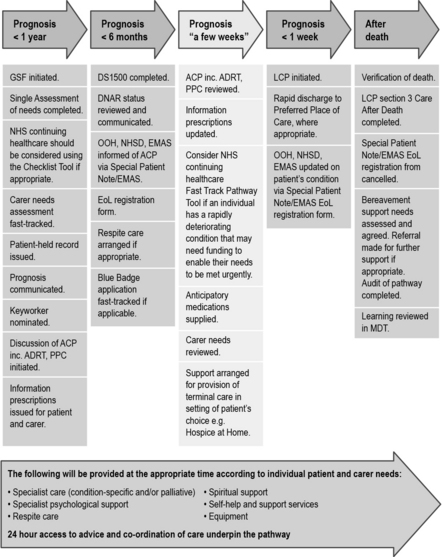

Some parts of the county have developed these six key steps into a structured patient pathway that spans the last year of life. By having a structured pathway, it is possible to start to consider planning care in advance with the patient and their family, with the aim to limit decisions being made in a time of crisis. Figure 16.1 is an example of one of these pathways used within a health community in Nottinghamshire.

Fig 16.1 Last Year of Life Pathway

(From Nottinghamshire End of Life Pathway for All Diagnoses (Next Stage Review Steering Group 2010). Reproduced with permission of NHS Nottingham City)

Consider the pathway in Figure 16.1 and make notes about what challenges might be faced by the patient, family and care team in each of the phases:

Now find out if your local health community has a specified pathway for last phase of life. It they do, how does it compare to the one in Figure 16.1?

The more definitive definition of end of life care used in the End of Life Care Strategy suggests it (DH 2008:47):

Best practice tools in end of life care

In England, there are several tools that have been developed that are considered to be ‘best practice’ tools in end of life care. These tools have been widely distributed through the National End of Life Care Programme Website (http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/, accessed November 2011) and are advocated by the End of Life Care Strategy (DH 2008). We now look at each of these tools and consider how they might be used across a range of practice placements.

Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP)

• The patient does not have pain.

• The patient is not agitated.

• The patient does not have respiratory tract secretions.

• The patent does not have nausea.

• The patient is not vomiting.

• The patient is not breathless.

• The patient does not have urinary problems.

• The patient does not have bowel problems.

• The patient does not have other symptoms. This can be a variety of things, for example an open wound needing dressing or a raised temperature.

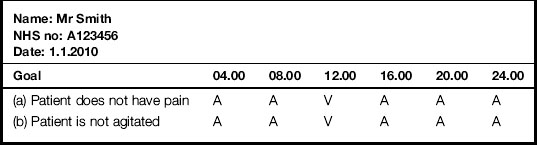

Looking at Mr Smith’s written record in Table 16.1, we see he was pain free and not agitated at 08.00 since it is indicated that these two goals had been achieved (A). However, at 12.00, we see there were signs of a variance (V) away from goals (a) patient does not have pain and (b) patient is not agitated. This means Mr Smith was in some way displaying signs of both pain and agitation.

Gold Standards Framework

1. The ‘surprise question: would you be surprised if this patient died within a week? If yes, then consider: would you be surprised if this patient died in a month? Six months? A year? The answer to this question can help the team consider if the patient is in the last phase of life. While we might be surprised if a patient we are caring for dies in a week, we might not be surprised if they die in 6 months’ time.

2. The patient with advanced disease makes a specific choice for comfort care only.

3. Clinical indicators of advanced disease are present: for example, increased agitation, falls, infections, pain and extreme fatigue. We look at these indictors later on in this chapter.

Preferred Priorities of Care

Understanding what a patient wants is very important when providing holistic care. The Preferred Priorities of Care (PPC) document was originally developed by Marie Curie Cancer Care to help focus attention on what is a priority for the patient; what it is they want and hope for. It is now kept up to date by the Preferred Priorities of Care Review Team (2011) and this latest version is available from the National End of Life Care Programme Website. Very often you will see families speaking out for a patient. They mean well and may say ‘He won’t want to go into hospital’ or ‘He wouldn’t want us upset by him dying in the house’. But how can we be sure this is what the patient wants? Instead, we need to be clear about what the patient wants, as well as understanding what is important to the family. Sometimes families can express their own fears and not the patient’s wishes. So what they may be saying to you is ‘I will feel so guilty if he goes into hospital’ or ‘How will we live in this house if he dies here’. The PPC contains various sections and supports patients in thinking though difficult issues and talking about the future.

Recognising dying and managing the last days of life

We have looked at some tools that can be used to help us care for the dying in their last phase of life. We now consider how we recognise dying in order to be able to use these tools. Recognising dying is not easy, even for the experienced professional (Furst & Doyle 2005). We must not take it for granted that other members of the team find this part of caring for a patient with advanced cancer simple and straightforward. Often the transition from curative cancer to last days of life care is complex. It can be a slow process or a sudden onset of new symptoms. Every patient must be assessed and treated individually. Patients tell us in many ways that they are dying. The challenge for the care team is to be aware of these signs to be able to recognise the dying.

List the ways you might become aware that a person is dying.

There are some core signs and symptoms that are associated with dying. The NCPC suggests the commonly reported symptoms prior to death are increased pain or changes in the pattern of pain, restlessness and confusion, noisy breathing, nausea and vomiting, incontinence and extreme fatigue (NCPC 2006b). Furst and Doyle (2005) add falls, infections, unable to get out of bed and not wanting to eat or drink to this list. Some work done in long-term care homes in America asked the nursing staff how dying was recognised there with their residents (Porock & Oliver 2007). The core themes that emerged from these conversations with care home staff, described as ‘patient cues’, are: an adverse event, a decision, ready to go, withdrawal and the look. Let’s see in detail what these five patient cues might look like in your practice placement.

Terminal agitation

Restlessness, confusion and delirium are also terms associated with agitation in the last days and hours of life. We refer to terminal agitation, but the words and terms can be used interchangeably. It is important to understand why agitation occurs since 85% of patients with cancer will experience some degree of agitation, restlessness, delirium or confusion in the last weeks of their life (Macleod 1997). Biochemical changes that occur in the body as end of life approaches can affect the body’s normal ability to filter and process stimulation and information received from the external environment, from within the body and from unconscious memories (Stedeford 1994). This means sensations and stimulation are not processed in the usual way and can become all muddled up, making it difficult for a patient to work out where the stimulation is coming from. For example, a simple noise may become frightening or a nurse call bell ringing may be interpreted as an alarm and may lead to a patient to try to get out of bed in fear. A full bladder might be interpreted as a memory from childhood leading the patient to call out for a deceased parent. A patient may be seen doing repetitive movements. To the patient these are purposeful, but for the family they can appear that the patient is distressed. Knowing about a person’s life, work and hobbies can help to interpret these movements; a patient swinging both arms when lying flat may be playing golf, or circling the arms round each other may be winding wool.

Accurate assessment of these changes is important by the whole care team and it is important to consider if there is anything that is reversible that might be causing the agitation. For example, a patient may be in withdrawal of nicotine if they have not been able to smoke a cigarette as they have deteriorated. Actions to reverse causes include replacing nicotine using patches, emptying the bladder, managing constipation or lowering a raised blood calcium level (Fig. 16.2). Once these have been tried, if the patient is still agitated it will probably mean that they are dying. It is always important to try to reduce anything that may be causing the agitation, even if this is the terminal phase, to reduce distress for the family. When caring for a patient with terminal agitation, it is important to keep stimulation in the environment to a minimum; encourage family members to read quietly at the bedside or bring in some favourite calming music to play softly.

Terminal secretions

Noisy secretions occur in approximately 80% of patients at the end of life (Hughes et al 2000) and are often referred to as the ‘death rattle’. This is more distressing for the relatives than the patient who, apart from having noisy breathing, can often be very settled and appear pain free. The secretions occur due to pooling of fluid in the pharynx which the patient does not have the energy to remove. This fluid can be saliva, produced as a result of an infection, pulmonary oedema or gastric reflux (Twycross et al 2009).

The care of people from different faiths before and after death

1. Finding out if there are any specific practices or rituals that are important for the patient and family.

2. First offices to ensure the deceased is clean and respectable for relatives who may want to visit immediately. This may include removing any unnecessary equipment from the bedside, washing the deceased’s hands and face, brushing their hair, putting in dentures, etc.

3. Supporting relatives to see the deceased and say goodbye, recognising spiritual and religious needs.

4. Recording of the patient’s property. Never remove jewellery without checking. If in doubt, leave it on ensuring it is accurately recorded before the deceased goes to the mortuary. Respect for property is important for relatives. Ensure it is folded and packed sensitively. Label all the bags with the deceased’s name.

5. Last offices are prepared immediately before the deceased is transferred to the mortuary and includes full wash, being dressed in a white gown or clothing of the patients’/relatives’ choice and takes into consideration infection control polices. When performing last offices, it is very important to be aware of cultural and spiritual practices important for the deceased and relatives.

6. Keeping relatives informed at all times of where the deceased is and when they are due to be transferred to the chapel of rest (mortuary).

http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/guidance-for-staff-responsible-for-care-after-death (accessed November 2011)

We now look at the some terms individually.

Culture

‘… the values, norms and characteristics of a given group … culture is one of the most distinctive properties of human social association …’ (Giddens 2009:1115). It is important to understand the strength culture has in the way a person behaves since, when a person comes into hospital, it is a meeting of their culture with our own personal culture and then the professional culture of our organisation (Holland & Hogg 2010).

Values

‘… ideas held by human individuals or groups about what is desirable, good or bad … what individuals value is strongly influenced by the specific culture in which they happen to live …’ (Giddens 2009:1136). Understanding the concept of values helps us with keeping our actions focused on what is important to the patient/family rather than our own perceptions of good and bad. This links to the ethical principles we explored in Chapter 5.

Religion

‘… a set of beliefs adhered to by members of a community involving symbols regarded with a sense of awe and wonder, together with ritual practices in which members of the community engage …’ (Giddens 2009:1130).

Ritual

‘… essential to binding members of groups together … they are found not only in regular situations of worship, but in various crises at which major social transitions are experienced … birth, marriage and death …’ (Giddens 2009:531).

Understanding links between culture, religion and ritual are important when we are supporting a patient and their relatives. This awareness helps us to understand the important role commonly shared beliefs provide in terms of meaning and purpose (Giddens 2009) and is fundamental to meeting spiritual needs at times of distress.

Remember that care of a person’s religious and cultural beliefs does not replace the care for their spiritual wellbeing. In Chapter 5, the definition of spirituality was introduced and an understanding of religion, culture and rituals helps to recognise spiritual needs.

Hinduism is the world’s oldest religion and has evolved over centuries, has its origins in the state of Gujerat, India, and believes in the worship of many Gods. Reincarnation and karma are sacred concepts meaning death is prepared for rather than feared. Running water and cleanliness are very important to Hindus and a person who has died is seen as unclean, as are those who visit and care for them. Table 16.2 shows just a few of the rituals that are important in the Hindu faith. Don’t forget that the patient, if well enough, and family are usually delighted to explain some of the rituals and beliefs. Don’t be afraid to say to a family that you don’t understand their rituals and practices. By asking, you are saying to them that it is important for you to know, therefore their beliefs and values are being respected too.

| Before death | At death | After death |

|---|---|---|

| Sprinkled with Holy water Family present Die near to mother earth Reciting of mantra/prayers Lamp lit near the head |

Sprinkled with Holy water Keep jewellery and threads Close eyes and mouth Mirrors covered Loud wailing |

Tulsi leaf (basil) in mouth Postmortem allowed Cremation within 24 hours Women wear white Wrap in plain white cloth |

http://www.ethnicityonline.net/ (accessed November 2011).

For further reading to develop more awareness, you might want to look at the chapter ‘Death and Bereavement: a Cross Cultural Perspective’ by Holland in Holland and Hogg (2010) (see References). This chapter emphasises the importance of recognising culture and rituals in peri-death care. It is also particularly informative on the impact of culture on the bereavement process.

Looking after ourselves

For the next 6 days in a row, think of a treat for yourself, one each day. Rules about the treat:

The following NHS Choices Website gives support and ideas to manage stress:

http://www.nhs.uk/livewell/stressmanagement/Pages/Stressmanagementhome.aspx (accessed November 2011)

National end of life care core competences

The End of Life Care Strategy (DH 2008) sets out clear guidelines for supporting the development of people working in health and social care who may be involved in a part of end of life care. These guidelines are called the Core Competences for End of Life Care (DH 2009) and are supported by a range of health and social care agencies. There are five overall themes in the core competences and seven principles underpinning end of life care.

The five themes in the core competences are the following:

1. Communication: engage effectively with patients/residents/families in discussions about death and dying.

2. Assessment and care planning: holistically assess, develop, implement and review a plan of care involving the family, patient or resident as appropriate.

3. Symptom management: provide quality symptom management with their level of competence and know when it is appropriate to refer to specialist palliative care.

4. Advance care planning: engage in advance care planning discussion with patients/families/residents and show awareness of legal and ethical issues surrounding the advance care planning process.

5. Overarching values and knowledge: demonstrate awareness of own values, knowledge and ongoing professional development in supporting people experiencing loss, grief and bereavement from a variety of social, cultural and religious backgrounds.

The seven principles underpinning end of life care are the following:

1. Choices and priorities of the individual are at the centre of planning and delivery.

2. Effective, straightforward, sensitive and open communication between individuals, families, friends and workers underpins all planning and activity. Communication reflects an understanding of the significance of each individual’s beliefs and needs.

3. Delivery through close multidisciplinary and interagency working.

4. Individuals, families and friends are well informed about the range of options and resources available to them to be involved with care planning.

5. Care is delivered in a sensitive, person-centred way, taking account of circumstances, wishes and priorities of the individual, family and friends.

6. Care and support are available to anyone affected by the end of life and death of an individual.

7. Workers are supported to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes. Workers take responsibility for, and recognise the importance of, their continuing professional development.

http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/corecompetencesframework (accessed November 2011)

Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008.

Department of Health. Core competences for end of life care. London: Department of Health; 2009.

Furst C., Doyle D.. The terminal phase. Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherny N., Calman K. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, 3rd ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Giddens A. Sociology, 6th ed. Cambridge: Polity; 2009.

Holland K., Hogg C. Cultural awareness in nursing and health care: an introductory text, 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold; 2010.

Hughes A., Wilcock A., Corcoran R., et al. Audit of three antimuscarine drugs for managing retained secretions. Palliative Medicine. 2000;14(3):221–222.

Macleod A. The management of delirium in hospice practice. European Journal of Hospice Care. 1997;4(4):116–120.

National Council of Palliative Care. End of life care strategy: the NCPC submission. London: NCPC; 2006.

National Council of Palliative Care. Changing gear: guidelines for managing the last days of life in adults. London: NCPC; 2006.

Next Stage Review Steering Group. The Nottinghamshire end of life care pathway for all diagnoses, issue 2. 2010. Nottinghamshire

Porock D., Oliver D. Recognizing dying by staff in long term care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2007;9(5):270–278.

Preferred Priorities of Care Review Team. Preferred priorities for care. Online. Available at. 2011. http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/assets/downloads/PPC_document_v22_rev_20111.pdf (accessed May 2011)

Stedeford A. Facing death: patients, families and professionals. Oxford: Sobell; 1994.

Twycross R., Wilcock A., Stark Toller C. Symptom management in advanced cancer, fourth ed. Nottingham: palliativedrugs.com; 2009.

National End of Life Care Programme guidance, http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/care-pathway/6-careafterdeath and http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/pubacpguide (accessed November 2011).

General Medical Council guidance on treatment and care towards the end of life, http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/publications/gmceoltreatmentandcare (accessed November 2011).

Ethnicity Online details of peri-death rituals across a range of religions and cultures, http://www.ethnicityonline.net/ (accessed November 2011).

National Council for Palliative Care, http://www.ncpc.org.uk/ (accessed November 2011).

Marie Curie Cancer Care, http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/ (accessed November 2011).

NHS Choices Website offers guidance on assessment and management of stress, http://www.nhs.uk/livewell/stressmanagement/Pages/Stressmanagementhome.aspx.