44 Care of the plastic and reconstructive surgical patient

Abdominoplasty: Surgical removal of abdominal fat and skin.

Augmentation Mammoplasty: Surgical procedure performed to enhance the size and shape of a breast.

Blepharoplasty: Procedure done to correct deformities of the upper or lower eyelid with excision of redundant skin or protruding fat.

Dermabrasion: Surgical planing of the skin with removal of the epidermis and portions of the superficial dermis for elimination of high spots or other irregularities in an uneven skin surface.

Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator (DIEP) Flap: Autologous breast reconstruction performed using an abdominal wall flap. Less abdominal wall damage is incurred using this technique.

Gynecomastia: Benign hypertrophy of breast tissue in males.

Inosculation: Vessel anastomosis from host to graft that allows for graft revascularization.

Latissimus Dorsi Flap: Reconstructive procedure involving donor site muscle, adipose tissue, and skin blood supply that is left connected and then tunneled to the mastectomy site.

Lipectomy: Surgical removal of fatty tissue.

Otoplasty: Surgical procedure done to reduce prominence of the ears.

Pedicle Flap: A preferred flap for wound tissue that is somewhat avascular, such as cartilage, bone, and tendon, or in the presence of avascular scar tissue and radiation-affected tissue. This type of flap is used to provide soft tissue closure while allowing blood vessels to remain intact.

Reduction Mammoplasty: Surgical removal of glandular tissue, fat, and skin from the breasts to achieve lighter, smaller, and firmer breast proportions.

Rhinoplasty: Reshaping or reconstruction of the nose when its shape has been altered as a result of trauma or when the patient is unhappy with its form.

Rhytidectomy: Surgical tightening of facial and neck muscles with removal of excess skin; commonly called a face lift procedure.

Tissue Expansion: Insertion and positioning of a temporary inflatable balloon or implant device under the skin, which is periodically increased in size through instillation of normal saline solution to promote expansion of the skin for reconstructive purposes.

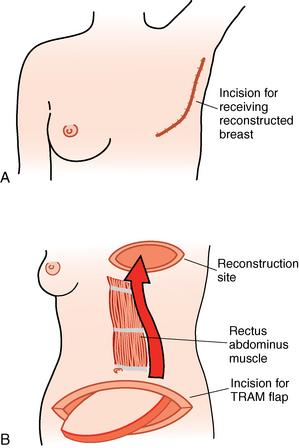

Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous (TRAM) Flap: This procedure is performed after a mastectomy and involves the reconstruction of a breast with autografting of lower abdominal muscle, skin, and adipose tissue. A pedicle TRAM flap uses the entire rectus abdominal muscle, whereas the free flap technique only partially involves this muscle.

Tumescent Liposuction: A dilute solution of lidocaine, used in combination with epinephrine, is injected into the adipose tissue layer to facilitate the vacuum removal of fat cells via a small cannula.

The field of plastic surgery encompasses cosmetic and reconstructive surgery, and related procedures and techniques have continuously evolved over time. This discipline is growing as consumer demand for cosmetic surgical procedures increases1 and the ability to achieve aesthetic reconstructive surgical outcomes improves.

Plastic surgery derives its name from the Greek word plastikos, which means to mold or give shape. The first successful tissue transfers are said to have originated in India more than 2500 years ago. Modern grafting techniques were explored in nineteenth-century Germany. Today, reconstructive procedures involve much more than the correction of acquired and congenital deformities. They are also performed to correct defects related to tumors, trauma, infection, burns and postburn contractures, pressure ulcers, or disease.2,3 Ideally, these procedures represent interconnected therapy4 that strives to restore normal function and enhance appearance to maintain or improve body image and self-esteem.5

Skin grafts

Skin grafting is the most common method for covering open areas that result from incomplete wound healing, trauma, burns, or large surgical incisions. Grafting involves the removal of a skin layer of varying thickness that is then transplanted to a host site. Transplanted skin layers can originate from the individual, be synthetic in origin, or be an expanded portion of the host’s own skin. The lower abdomen supplies a good source for the full-thickness skin graft.6

The major types of skin grafts are outlined in Box 44-1. Revascularization generally takes 3 to 5 days and requires growth of vessels from the host or the recipient tissue via a process called inosculation. For cosmetically pleasing results, the color, texture, thickness, and hair-bearing nature of the skin used for grafting should be chosen to match the recipient site. As a rule, the closer the donor skin is located to the recipient area, the better the match.

Box 44-1 Major Types of Skin Grafts

• A full-thickness graft includes all underlying dermis and epidermis and a small amount of subcutaneous tissue. These grafts, used to cover areas such as the nasal tip, dorsum, ala, and sidewall of the lower eyelid and ear, are more prone to necrosis.

• A split-thickness graft includes a portion of the underlying dermis and the entire epidermis. This graft is the least durable. It can be thin, medium, or thick, depending on the amount of dermis included.

• A composite graft comprises two or more tissue components and often includes skin and subcutaneous tissue, cartilage, or mucosa that can be used to reconstruct a patient’s ear, nose, or eyelid.

• A free cartilage graft involves a portion of cartilage that is harvested and reimplanted to provide structure and support to the site. One example is the use of rib cartilage to create an ear structure in a patient with microtia.

• An autograft indicates that the donor and the recipient are the same person.

• An isograft signifies that the donor and the recipient are genetically identical.

• Allograft or homograft means that the donor and the recipient are of the same species; this procedure may entail the use of cadaver tissue.

• A xenograft indicates that the donor and the recipient are of different species (e.g., porcine or bovine sources).

• Bioengineered skin and skin substitutes contain cells that may be animal, human, or host hybrids which acclimatize to the wound and accelerate healing. The mechanism of action is unknown.

Factors that influence graft survival include: adherence to the recipient tissue; adequate vascularity signs, which include color and capillary refill of site; close monitoring of graft tissue for early identification of complications; and strict management of oxygenation, hemodynamic stability, thermoregulation, pain control, and positioning. Postoperative monitoring and assessment for serum or blood in the graft site is important during the first 24 hours. Excess fluid can cause the graft to lift from its bed and must be removed. The donor site should be kept clean, and heals by forming a new layer of skin.7 Many variations exist in the type of wound dressing used, use of pressure dressings, required positioning of the patient, use of ice or antibiotic ointments, and handling of donor sites.

Every effort should be made to keep the patient calm and still and to prevent touching, removing or shifting of dressings. Some dressings, such as the bolster dressing shown in Fig. 44-1, may actually be sutured in place. Generally, the grafted area should be elevated and protected from both pressure and motion. The patient should be positioned to prevent any pressure on or other trauma to the graft or the donor site. The surgeon may order cold packs to reduce metabolic requirements of the graft and enhance its chances of survival. Dressings over grafts should be observed closely for drainage. The presence of excess drainage should be reported to the physician.

Flaps

Microvascular tissue transfer and free flaps

The most serious complication in a microvascular tissue transfer procedure is tissue necrosis. Tissue death occurs when the artery or the vein that supplies the flap develops a thrombus. Arterial thrombosis can result in complete flap failure within 4 hours of onset. Arterial occlusion is characterized by a pale cool flap that does not bleed when stuck with a needle. Hematomas can form at the recipient site and occur more commonly in the patient who preoperatively smokes or uses nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or corticosteroids.8

Venous thrombosis is more commonly encountered, but it is not an immediate threat. Thrombosis is characterized by a congested warm mottled flap that continuously oozes dark blood. Objective assessment of the flap is possible with fluorometry, transcutaneous oxygen tension, thermometry, laser Doppler scan, temperature monitoring, buried Doppler probe, or photoplethysmograph disk for monitoring of blood flow. Any change in skin color from the normal baseline or monitoring findings that indicates imminent occlusion should be reported to the surgeon immediately. A donor site typically generates more painful stimuli than the transplanted skin graft or flap site.9 Pain management should be individualized and based on the patient’s self-reported pain levels. Nursing care should include administration of analgesics and selected nonopioid adjuvants with attention to comfort measures as needed.

Breast reconstruction flap techniques

Breast cancer affects millions of women across the world each year, and reconstruction after mastectomy has become a routine part of breast cancer treatment. Breast reconstruction using autologous grafting is commonly accomplished in several ways, does not adversely affect cancer survival rates, and can serve to enhance the patient’s psychologic state. The transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap procedure involves the reconstruction of a breast with autografting of lower abdominal muscle, skin, and adipose tissue. The procedure can be performed using a pedicle TRAM flap or a free TRAM flap (Fig. 44-2). The pedicle TRAM procedure was first developed in the early 1980s. Through improved understanding of flap physiology and surgical techniques, common procedural options have evolved to include the use of a free TRAM flap, muscle sparing free TRAM flap, and deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap. All these flap procedures use a segment of abdominal muscle mass to achieve the breast graft. This muscle resection has frequently resulted in an abdominal bulge, abdominal hernia, and some degree of permanent loss of the patient’s abdominal strength. These findings occur at a lower incidence rate in the DIEP patient population. Surgeons performing the TRAM technique may choose to implant propylene mesh at the time of resection to better support the abdominal wall.10

Another procedure available for use in autologous breast reconstruction is the latissimus dorsi flap (LD) technique. The LD flap procedure is especially useful in the low body mass index patient who lacks the abdominal tissue reserves needed for flap harvest.11 Although a functional option, this procedure has been associated with less overall patient satisfaction than with the abdominal graft options.10 As with all postoperative flap procedures, nursing care of the postoperative breast reconstruction patient centers on observation of the graft site in addition to general perianesthetic breast surgery patient care (see Chapter 43).

Implications for practice

Patients may have several options for the type of reconstructive breast flap procedure performed. Preoperative discussions surrounding the available breast surgery techniques and related patient satisfaction outcomes may better assist a patient in making an informed decision about the course of treatment pursued.

Source: Yeuh JH, et al: Patient satisfaction in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a comparative evaluation of DIEP, TRAM, latissimus flap, and implant techniques, Plast Reconstr Surg 125:1585−1595, 2010.

Bone grafts

After bone grafting has been performed, the graft site must be immobilized, and excessive movement of the patient should be avoided. The donor site is generally the greater source of postoperative discomfort over the graft site.9 Pain should be anticipated and aggressively managed with opioid analgesics. If split-rib grafts are used, the patient should be placed in a low Fowler position. Respiratory status should be frequently assessed, and any signs of possible pneumothorax, such as tachycardia and tachypnea, should be reported immediately to the surgeon. Ice often is applied for reduction of swelling and pain management, and the graft site may necessitate elevation.

Surgical repair of facial bone injuries

When interdental wire fixation is performed, opening of the jaws may become necessary if an airway emergency develops (see Chapter 32 for care of the patient with interdental fixation). A pair of wire clippers should be clearly visible and affixed to the head of the bed to facilitate rapid opening of the jaws if needed. Good oral hygiene is a priority for these patients, and petrolatum ointment should be applied to the lips to prevent drying and cracking.

Surgical repair of cleft lip and palate

Cleft lips and palates are among the more common congenital defects encountered in the U.S. population.12 Children born with these defects may have associated problems, including facial growth abnormalities, dental irregularities, speech difficulties, ear diseases, psychological disorders, and cosmetic challenges. The infant with a cleft palate generally encounters difficulty nursing and swallowing. Repair of the cleft lip (Figs. 44-3 and 44-4) is usually accomplished when the “rule of 10” is met: 10 weeks of age, a body weight of at least 10 lbs, and a hemoglobin level of at least 10 g/dL. Repair is accomplished with general anesthesia, with palatal, maxillary regional nerve blocks available for use.13,14

On PACU admission, the infant is placed in a semiprone position, and the arms should be guided away from the operative site to avoid disruption of the newly repaired lip. Postoperative complications can include acute airway obstruction, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, bleeding, and aspiration of secretions and blood.15 Hemorrhage, although rare, is a possible complication. Because loss of even a few milliliters of blood in an infant can be significant, any bleeding requires rapid control intervention. Measures should be taken to minimize crying because it puts excessive tension on the newly repaired lip, and the parents should be present at the earliest possible time to facilitate soothing of the child. Depending on the type of anesthesia and intraoperative opioid dosing used, postoperative pain medication or sedation may be needed to comfort the infant. In addition to preventing lip trauma, the most important nursing activity is airway management. Humidified mist should be used to promote general respiratory well being and aid in clearing of secretions. In some cases, a nasal trumpet can be used to maximize oxygenation and may be sutured to the nostril to prevent dislodgement. When the child is fully awake from the anesthesia small sips of clear fluids may be given. Pain status, although difficult to assess in an infant, must be evaluated. Analgesia should be provided when indicated, and oral analgesics such as acetaminophen can be used. Iced normal saline solution–soaked gauze can be applied to the suture areas to reduce swelling and promote comfort.

Cleft palate

Depending on the extent of the palate defect and accompanying lip defect, if present, repair may be completed when the child is 6 to 18 months of age. Optimization of speech and feeding is often a priority. The repair can be phased, requiring multiple procedures that include palatoplasty with bone grafts and orthodontic inserts.16 Certain procedures, such as nasoseptal reconstructions, can be delayed until the child becomes a teenager. On admission to the PACU, the child is placed in the semiprone or “tonsil” position with careful attention given to airway maintenance. As in cleft lip repair, the child’s arms should be guided away from the surgical site, and crying should be avoided. The head should not be flexed because this position tends to occlude the airway. Suctioning may be necessary but must be performed gently and only if the nurse’s view is unobstructed. The catheter, plastic dental suction tip, or Yankauer suction tip should be passed over the dorsum of the tongue, and only minimal vacuum pressure should be used. A mist tent or cold-mist humidifier should be used to aid in the elimination of secretions. Pain should be assessed and managed with opioids and adjuvants as indicated. Hemorrhage is a possible complication, and any active bleeding requiring control should be reported to the surgeon.

Cosmetic surgery

Blepharoplasty

Blepharoplasty is a procedure to correct deformities of the upper or lower eyelid with excision of redundant skin or protruding fat. The procedure may be performed for a cosmetic benefit or when eyelid drooping impedes vision.17 The procedure is usually performed with local anesthesia with supplemental intravenous sedation. Iced compresses minimize swelling and bleeding. The patient may resume a regular diet after surgery; however, hot liquids are contraindicated for 24 hours to prevent vasodilation and bleeding. Activities such as bending and heavy lifting should be avoided. Pain should be assessed and managed with appropriate analgesics. Drugs that alter coagulation times should be avoided. Antibiotic ointment may be used for lubrication (see Chapter 33).

Dermabrasion

Usually the dermabraded areas are treated with the open method, and postanesthesia care includes protection of those areas from abrasion caused by rubbing on pillows or bed clothing. Facial edema, especially of the eyelids, may be expected, and the patient must be reassured that this subsides rapidly. The dermabraded area should be observed closely for the development of moisture. If moisture develops, it should be dried with a heat lamp or a warm hair dryer. This procedure can produce an uncomfortable burning sensation for the patient and can be minimized by holding the lamp or dryer a considerable distance from the area to be dried. Appropriate analgesics should be administered to manage painful sensations.

Liposuction

Suction lipectomy (liposuction) removes subcutaneous fat to improve facial or body contours. It may be used in conjunction with other techniques. Liposuction is commonly performed on a same-day surgical basis, and anesthesia administration is local or general. However, if greater than 2500 mL of fat is removed, fluid replacement and an overnight admission may be required. In the tumescent liposuction approach, pain should be minimized because of local lidocaine infiltration, but the dose of tumescent lidocaine should not exceed 55 mg/kg.18 However, if large areas are treated, an opioid analgesic could be required, and intravenous fluid replacement is needed. Postoperative bleeding and infection are possible complications. Drugs that alter coagulation times should be avoided. The patient can usually start oral fluids and a progressive diet as soon as pharyngeal reflexes have returned. Measures used to minimize discomfort, prevent fluid shifts, seroma or hematoma formation and ecchymosed areas include having the patient wear a binder, girdle, or elastic tape over the areas treated.18

Rhytidectomy

Rhytidectomy, commonly known as a face lift, is usually done with local anesthesia with supplementary sedation. It sometimes involves general anesthesia requiring PACU Phase I admission. The goal of the procedure is to lift and enhance facial soft tissue and skin, which gradually declines with age. The original procedure developed in the early 1970s involved repositioning of soft tissue and skin, but today include alloplastic implants and synthetic fillers.19 Postoperatively, elevation of the head of the bed and promotion of a quiet atmosphere are indicated. Pain should be assessed and appropriately treated. Pain located on one side only is unusual and may indicate a potentially serious bleeding complication, which is more commonly found in patients with hypertension. Bleeding and hematoma formation can compromise the patient’s airway and necessitate further surgical intervention; therefore the surgeon should be notified immediately when bleeding occurs.

Summary

Primary postoperative concerns for this patient population include viability of flaps or transplanted tissue, minimization of and assessment for postoperative bleeding, conservative management of surgical sites and dressings, and aggressive pain control to facilitate healing and the patient recovery process. Psychosocial concerns and cosmetic outcomes are often a unique priority in this patient population. This personalized focus could significantly affect the course of care, the perianesthetic treatment and education performed, and the psychosocial integrity of the postoperative patient. Positive procedural outcomes, regardless of the surgical site, technique, or technology, require preparation, vigilance, and prompt intervention on the part of the perianesthesia nurse.

1. Hotta T. Plastic surgery on the rise. Plast Surg Nurs. 2011;31:45–46.

2. Mahmoud SM, et al. Split-skin graft in the management of diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care. 2008;17:303–306.

3. Maillard GF, Garey L. Plastic surgery after ablative cancer surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30:47–52.

4. Knobloch K, Vogt PM. The reconstructive clockwork as a 21st century concept in wound surgery. EWMA J. 2011;11:25–27.

5. Borwick G. A holistic approach to meeting the needs of patients with conditions that affect their appearance. Primary Health Care. 2011;21:33–38.

6. Jabaiti SK. Use of lower abdominal full-thickness skin grafts for coverage of large skin defects. Eur J Sci Res. 2010;39:134–142.

7. Spear M, Bailey A. Treatment of skin graft donor sites with a unique transparent absorbent acrylic dressing. Plast Surg Nurs. 2009;29:194–200.

8. Kaplan ED. Preventing postoperative haematomas in microvascular reconstruction of the head and neck: lessons learnt from 126 consecutive cases. ANZ J Surg.2008;78:383–388.

9. Davies SL, White RJ. Defining a holistic pain-relieving approach to wound care via a drug free polymeric membrane dressing. J Wound Care. 2011;20:250–256.

10. Wan DC, et al. Inclusion of mesh in donor-site repair of free tram and muscle-sparing free tram flaps yields rates of abdominal complications comparable to those of DIEP flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:367–374.

11. Elliott FL, et al. The scarless latissimus dorsi flap for full muscle coverage in device-based immediate breast reconstruction: an autologous alternative to acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg.2011;128:71–79.

12. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: Craniofacial birth defects. available at: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/FindDataByTopic/CraniofacialBirthDefects/, August 22, 2011. Accessed

13. Jonnavithula N, et al. Efficacy of palatal block for analgesia following palatoplasty in children with cleft palate. Pediatr Anesth. 2010;20:727–733.

14. Mesnil M, et al. A new approach for peri-operative analgesia of cleft palate repair in infants: the bilateral suprazygomatic maxillary nerve block. Pediatr Anesth.2010;20:343–349.

15. Kwari DY, et al. Cleft lip and palate surgery in children: anaesthetic considerations. Afr J Paediatr Med.2010;7:174–177.

16. Eichhorn W. Influence of lip closure on alveolar cleft width in patients with cleft lip and palate. Head Face Med. 2011;7:3.

17. Perkins SW, Prischmann J. The art of blepharoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27:58–66.

18. Coldiron B, et al. ASDS guidelines of care for tumescent liposuction. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:709–716.

19. Hopping SB, et al. Volumetric facelift: evaluation of rhytidectomy with alloplastic augmentation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryng.2010;119:175–180.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons: Reconstructive procedures. available at: www.plasticsurgery.org/Reconstructive-Procedures.html, July 14, 2011. Accessed

Barlow JO. The placement of structural cartilage grafts under full-thickness skin grafts: a case series and strategies for successful outcomes. Dermatol Surg.2010;36:1166–1170.

Bullocks J, et al. Plastic surgery emergencies: principles and techniques. New York: Thieme; 2008.

Habbema L. Safety of liposuction using exclusively tumescent local anesthesia in 3,240 consecutive cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1728–1735.

Hivelin M, et al. Ultrasound-guided bilateral transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia after breast reconstruction by DIEP flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:44–55.

Lazic T, Falanga V. Bioengineered skin constructs and their use in wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;127:756S–790S.

Patel KM, et al. Management of massive mastectomy skin flap necrosis following autologous breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 67, 2011. DOI:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182250e23.

Stephan B, et al. The use of antithrombotic agents in microvascular surgery. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;43:51–56.

Turgut G. Nipple reconstruction with bipedicled dermal flap: a new and easy technique. Aesth Plast Surg.2009;33:770–773.

Wei FC, Mardini S. Flaps and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.