37 Care of the orthopedic surgical patient

Anesthesia: Local or systemic loss of sensation.

Arthrodesis: Surgical fixation or fusion of a joint.

Arthroplasty: Reconstruction of joints for restoration of motion and stability.

Arthroscopy: Surgical examination of the interior of a joint with the insertion of an optic device (arthroscope) capable of providing an external view of an internal joint area.

Arthrotomy: Surgical exploration of a joint.

Articulation: The connection of bones at the joint.

Cineplastic (Kineplastic) Amputation: An amputation that includes a skin flap built into a muscle; a portion of the prosthetic mechanism is activated by the muscle.

Disarticulation: Amputation at a joint.

Diskectomy (Discectomy): Removal of herniated or extruded fragments of an intervertebral disk.

External Fixators: Equipment used in the management of open fractures with soft tissue damage (provides stabilization for the fracture while it permits treatment of soft tissue damage).

Fasciotomy: Surgical separation of the fascia (a fibrous membrane that covers, supports, or separates the muscles) for relief of muscle constriction or reduction of fascia contracture.

Harrington Rods: Equipment used in spinal fixation for scoliosis and for some spinal fractures.

Hemiarthroplasty: Replacement and resurfacing of the femoral head with a prosthesis.

Internal Fixation: The stabilization of a reduced fracture with the use of metal screws, plates, nails, and pins.

Joint Replacement: The substitution of joint surfaces with metal or plastic materials.

Laminectomy: Removal of the lamina for exposure of the neural elements in the spinal canal or relief of constriction.

Lordosis: Abnormal anterior convexity of the lower part of the back.

Luque Rods: Contoured metal rods that are fixed to each segment (vertebrae) in the affected part of the spine.

Meniscectomy: Surgical removal of the damaged knee joint fibrocartilage.

Open Reduction: The reduction and alignment of a fracture through surgical dissection and exposure of the fracture.

Osteoporosis: Diminished amount of calcium in the bone.

Osteotomy: Surgical cutting of the bone.

Paresthesia: Numbness and a tingling sensation.

Scoliosis: Lateral curvature of the spine.

Sequestrectomy: Surgical removal of necrotic bone.

Spinal Fusion: A fusion of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar region of the spine with an iliac or other bone graft that primarily fuses the laminae and sometimes the joints, most often through the posterior approach.

Syme Amputation: Modified ankle disarticulation (below-the-ankle) amputation of the foot.

Volkmann Contracture: The final state of unrelieved forearm compartment syndrome; contractures of tendons to wrist and hand.

General perianesthesia care

Specific nursing care related to the patient for orthopedic surgery that begins in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) includes positioning, neurovascular assessment, care of immobilization devices, wound care, range-of-motion exercises, and observation for complications.

Positioning

Shoulder immobilization can be accomplished with a sling or shoulder immobilizer. An airplane splint (a padded and Velcro shoulder orthotic used to position the shoulder in various degrees of abduction; Fig. 37-1) may be applied for rotator cuff repairs and other involved humerus fractures and postoperative shoulder or arm surgery where shoulder position and elbow flexion control are desired. If a sling is used, the patient is instructed to keep the arm close to the chest, with the wrist and elbow supported. All shoulder immobilizers require special care and padding to areas where skin contacts skin.

FIG. 37-1 Airplane splint.

(From Coppard BM, Lohman H: Introduction to splinting: a clinical-reasoning and problem solving approach, ed 2, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby.)

For the patient with a posterior or lateral total hip replacement, proper body alignment is achieved with placement of an abduction pillow between the knees at all times (Box 37-1). Most important with these patients is to avoid flexion and adduction of the newly placed joint. There are four basic positions to be avoided after hip surgery: 1) no flexion of the hip past 90 degrees with respect to the axis of the body; 2) no abduction of the leg past the midline of the body; 3) no combined extension of the hip joint with external rotation of the lower extremity; and 4) no flexion with internal rotation. Use of the abduction pillow helps to prevent the patient from getting into positions that could cause dislocation. The patient who has had an anterior total hip replacement does not require dislocation precautions. Therefore there is no need for an abduction pillow, traction sling, or hip cushion to assist with positioning.1

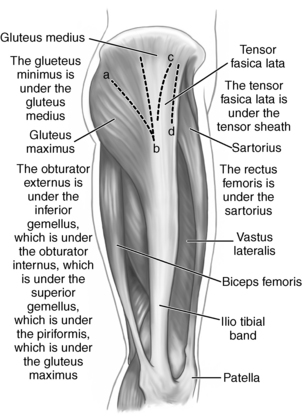

BOX 37-1 Surgical Approaches for Total Hip Arthroplasty

1. The posterior approach (i.e., Kocher-Langenbeck approach) splits the gluteus maximus muscle and detaches the posterior external rotator muscles (i.e., the piriformis, obturator internus and externus, superior and inferior gemellus).

2. The lateral or transgluteal approach (i.e., Harding approach) splits the gluteus medius muscle and detaches the gluteus minimus and the anterior third of the gluteus medius muscles from the femur.

3. The anterolateral approach (i.e., Watson-Jones approach) is performed posterior to the tensor fascia lata and anterior to the gluteus medius and splits the hip deltoid muscle, which consists of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata muscles.

4. The anterior approach (i.e., short Smith-Petersen and Hueter approach) does not split or detach muscles. This approach is performed over the tensor fascia lata, inside the tensor sheath, anterior and medial to the tensor fascia lata, and lateral to the sartorius and rectus femoris muscles.

(From Munro CA: The perioperative nurse’s role in table-enhanced anterior total hip arthroplasty, AORN J 90:54, 2009. Illustration by Kurt Jones.)

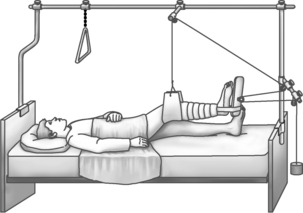

The perianesthesia nurse should also be familiar with various types of orthopedic equipment that may be used and that can affect positioning. Often, patients with total knee replacement and those with more extensive knee arthrotomy are placed in a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine. The purpose of CPM is to enhance the healing process by providing CPM to the joint, thus increasing circulation and movement. Traction may also be used with various patients to immobilize and align a specific area. The perianesthesia nurse is not usually involved in setting up the traction, but should be aware of some basic principles for maintenance: (1) the traction must be continuous, (2) the patient is centered in bed in good alignment to maintain the line of pull in line with the long bone, (3) weights should hang freely and not resting on the floor or bed, and (4) the pulley ropes should be in alignment and free of knots. One type of traction is depicted in Fig. 37-2.

Neurovascular assessment

Critical to the care of the patient for orthopedic surgery is assessment of the neurovascular status of the operative limb. Any alteration in blood flow to the extremity or nerve compression requires immediate intervention. Assessment is recommended every 30 minutes because problems can occur within 2 to 4 hours. Baseline neurovascular indicators should be noted in the admission nursing assessment. These indicators can be used to establish any deleterious effects from the surgery and to avoid the masking of potential complications. Both the affected and unaffected limbs are assessed.2

The hallmarks of neurovascular changes from constriction and circulatory embarrassment are pain, discoloration (skin that is pale or bluish), decreased mobility, coldness, diminished or absent pulses, altered capillary refilling, and swelling. Pain is common with patients for orthopedic surgery, and the approach to treatment must be individualized. Pain unrelieved with conventional methods, such as elevation and repositioning and the administration of opioids, must be assessed further. Color indicates circulatory compromise.2 Cyanosis suggests venous obstruction; pallor suggests arterial obstruction. Mobility is assessed by determining the range of motion of the fingers or toes and strongly indicates neural compromise. Fingers are flexed, extended, spread, and wiggled. Toes should be dorsiflexed, plantarflexed, and wiggled. An inability to move the fingers or toes, pain on extension of the hand or foot, or coldness of the extremity is indicative of ischemia. Sensation is described as normal, hypesthetic (dulled), paresthetic, or anesthetic. Alteration in sensation suggests nerve compression or circulatory compromise. Limb perfusion is further assessed with the presence of peripheral pulses and capillary refilling. Capillary refilling is assessed with compression of the nail bed, which causes blanching; when the compression is released, color briskly returns. Compromise delays the filling time. With the development of pulse oximetry, a more reliable method of perfusion assessment is available. With placement of the oximeter sensor on a finger or toe of the affected limb, the pulsation is sensed and oxygen saturation is displayed. This method is more reflective of perfusion than capillary refilling and is valuable when pulses cannot be assessed because of the presence of a cast or dressing.

Care of immobilization devices (cast care)

The cast is a rigid immobilization device molded to the contours of the part to which it is applied. The cast has a dual purpose: immobilization in a specific position and provision of uniform pressure on the encased soft tissue. The cast should be inspected for visibility of fingers and toes for neurovascular assessment. If the cast is bivalved, the edges should be inspected for roughness to avoid discomfort and potential skin breakdown. When the patient arrives in the PACU, the cast is likely still wet, and special care must be taken to prevent indentations. A wet cast must be handled carefully with the palms of the hand to avoid pressure from fingertips. The cast should be supported on a pillow, and hard flat surfaces should be avoided. Improper handling and flat surfaces can cause indentations that can lead to the development of pressure sores. More frequently, a fiberglass cast is applied with quicker drying properties, but the same general principles still apply.2 In general, a full cast may not be placed on a patient where wound drainage is expected (a temporary splint or cast would be used), but any drainage noted on the cast should be circled, and the time should be noted. This documentation can provide a guide for postoperative blood and fluid loss and can alert the nurse if the drainage appears to be excessive. Note that orthopedic wounds tend to ooze and may bleed more than other surgical wounds.

Observation for complications

Deep vein thrombosis

Prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a major concern for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, especially total joint replacement.3 Other contributing risk factors include age, previous history of DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE), metastatic malignancy, smoking, estrogen or current pregnancy, vein disease, obesity, and genetics (Box 37-2). Thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot associated with three conditions outlined by Virchow in 1846: venous stasis, altered clotting mechanism, and altered vessel wall integrity.4 Immobilization and the insult of the surgical procedure place the orthopedic patient at high risk. DVT refers to the formation of a thrombus within the deep vein, typically the thigh or calf. In reports of total hip arthroplasty before routine prophylaxis, venous thrombosis occurred after total hip replacement in 50% of patients, and fatal pulmonary emboli occurred in 2%.3 Immobilization impairs the leg muscle action needed to move the blood sufficiently, and the surgical procedure injures vessel walls that activate and alter clotting mechanisms. An inflammation process begins within the vessel wall and leads to deep vein thrombosis. The patient usually has pain and tenderness. Signs include swelling and sometimes localized redness. Palpation of the calf reveals firmness or tension of the muscle. A positive Homans sign may be seen, although a positive sign does not accurately diagnose a DVT alone.5 DVT can be difficult to diagnose. Diagnostic tests such as venography, magnetic resonance imaging, or Doppler ultrasound may be indicated.

| Clinical Risk Factors | Hemostatic Abnormalities (Hypercoagulable States) |

|---|---|

| Advanced age | Antithrombin III deficiency |

| Fracture of pelvis, hip, femur, or tibia | Protein C deficiency |

| Paralysis or prolonged immobility | Protein S deficiency |

| Prior venous thromboembolic disease | Dysfibrinogenemia |

| Operation involving abdomen, pelvis, or lower extremities | Lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibodies |

| Obesity | Myeloproliferative disorder |

| Congestive heart failure | Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia |

| Myocardial infarction | Disorders of plasminogen and plasminogen activation |

| Stroke |

Adapted from Anderson FA, Spencer FA: Risk factors for venous thromboembolism, Circulation 107:S19, 2003; Lieberman JR, Hsu WK: Current concepts review: prevention of venous thromboembolic disease after total hip and knee arthroplasty, J Bone Joint Surg 87A:2097, 2005.

Prevention of DVT includes providing adequate hydration, early mobility, and exercise and applying compression elastic stockings and external compression devices to enhance venous flow. Rehabilitation beginning the first day after surgery will help to prevent venous complications. The pneumatic stockings (alternating–pressure gradient stockings) automatically provide a consistent compression-decompression system and are used in patients having many surgical procedures, including total hip replacement and spinal surgery. Surgeon’s preference typically dictates the choice of postoperative anticoagulant therapy for patients at high risk, such as those with total joint replacements. The ideal agent for pharmacologic prevention of DVT has not been determined.3 Most hospitals use a detailed DVT prophylaxis screening tool or protocol to assess each patient’s individual need for anticoagulation therapy and thromboprophylaxis. All health care facilities who are accredited by The Joint Commission must comply with National Patient Safety Goal 03.05.01 to “take extra care with patients who take medication to thin their blood.”6

Pulmonary embolism

The most serious sequela of deep vein thrombosis is PE. The severity of symptoms depends on the size and number of clots. Symptoms range from none if the clot is small to a myriad that may include, with increasing severity, anxiety, dyspnea, tachypnea, hemoptysis, substernal pain, stabbing pleuritic pain, tachycardia, cough, signs and symptoms of cerebral ischemia, fever, elevated sedimentation rate, shock, and sudden death. Immediate nursing care involves administration of oxygen and relief of pain. Medications usually include heparin-bolus doses with continuous infusion or other antithrombolytic agents. After hip surgery, thrombus formation may occur in the thigh, making it more likely that a PE may occur. After knee surgery most thrombi occur in the calf and are less likely to lead to PE,3 but perianesthesia nurses must be vigilant for signs and symptoms of DVT and PE.

Fat embolism syndrome

Fat embolism syndrome is a condition that leads to respiratory insufficiency and is related to multiple fractures, especially of the long bones. It is caused by fat droplets released into the circulation from the bone marrow and local tissue trauma. Similar to pulmonary embolism, these fat globules migrate to the lungs, where they cause occlusions. The fat globules break down into acids and irritate vascular walls and cause extrusion of fluids into the alveoli. The lung involvement alters ventilation and leads to hypoxemia. Fat embolism syndrome can lead to adult respiratory distress syndrome. The symptoms related to lung involvement include tachypnea, tachycardia, anxiety, chest discomfort, petechiae over the chest, PO2 less than 60 mm Hg, fever, pallor, and confusion.7 Brain involvement is evidenced by agitation, confusion, delirium, and coma. Immediate nursing care of this sometimes-fatal complication includes administering oxygen, keeping the patient quiet, and preventing motion at the fracture site. Prompt ventilation-perfusion scans may be warranted.

Compartment syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a condition in which increased pressure within a muscle compartment causes circulatory compromise and leads to tissue necrosis and diminished function of the limb. Left undetected, the compression may cause permanent damage to the extremity. The compartment is described as a fascial sheath that encloses bone, muscle, nerves, blood vessels, and soft tissue. The two main causes of increased pressure to this space are: (1) constriction from the outside, such as a cast or bandage that decreases the size of the compartment, or (2) increased pressure within the compartment, such as swelling. The hallmark symptoms of compartment syndrome include intense pain unrelieved with conventional methods, paresthesia, and sharp pain on passive stretching of the middle finger of the affected arm or the large toe of the affected leg. The most significant sign is pain that is out of proportion to that expected with the injury or surgery.3 Progressive symptoms include decreased strength, decreased sensation (numbness and tingling), and decreased capillary refilling; peripheral pulses are not generally compromised. Immediate intervention includes elevation of the extremity, application of ice, and release of restrictive dressings. Compartmental pressures may be determined by the surgeon. If compartmental pressures are greater than 30 mm Hg in the presence of clinical findings, immediate fasciotomy is indicated. Ambiguous readings require continuous monitoring and continued clinical examinations (Fig. 37-3).3 Fasciotomy may be required within 4 to 6 hours of onset of symptoms if conservative measures are unsuccessful.

Shock

Because of the highly vascular composition of bone and secondary injury to the soft tissue, hemorrhage is always a potential risk after trauma and orthopedic surgery. Vigilant observation of the operative area and blood pressure and pulse alerts the perianesthesia nurse to any impending danger. Immediate nursing measures include keeping the patient warm and flat in bed, monitoring vital signs, and replacing fluid volume. The surgeon is notified immediately, and more definitive treatment is initiated (see Chapter 54).

Perianesthesia care after hand surgery

Hand surgeries have become highly specialized, and there are numerous procedures including carpal tunnel release, excision of ganglions, fractures of carpal bones, or digit reimplantation.8 There are several anesthesia options for patients undergoing hand surgery. Regional blocks to selectively block sensory functions of specific nerves are frequently used; these include digital blocks, wrist blocks, IV regional blocks, and axillary blocks. Therefore, many times patients with hand surgery bypass PACU Phase I and are admitted directly to PACU Phase II. Large bulky dressings may be in place on the hand and forearm. Ace wraps or elastic bandages for application of pressure may also be in place outside the dressing. The hand should be elevated above the level of the heart at all times to prevent edema and hemorrhage. The hand may be placed on pillows on the chest of the patient or suspended from the bed frame or IV pole with a stockinette. The elbow should be supported with a pillow. Support under the shoulder and wrist aids in decreasing pressure to the elbow. If a drain is present, it should be checked to ensure that it is activated, or it may be connected to a vacuum blood tube. The drain is placed to minimize the bleeding into the wound and to reduce the possibility of infection. Drains should be checked every 1 or 2 hours to maintain a proper vacuum, and the output should be recorded on the intake and output records. The tips of the fingers should be visible, and the neurovascular status should be assessed every 30 minutes for signs of change. If a regional block is used for anesthesia, the perianesthesia nurse must be aware that the patient’s sensation and movement might not fully return for several hours after surgery and extremities must be protected from injury. Baseline neurovascular indicators should be noted in the admission nursing assessment and can be used to establish any deleterious effects from the surgery.

Perianesthesia care after shoulder surgery

Inspection should include checking to see whether any skin surface is in contact with another. If this situation occurs, a protective pad should be inserted between the two skin surfaces. The radial pulse should be monitored, because flexion of the arm in the immobilizer can reduce blood flow to the hand. The immobilizer should be checked for areas that might be causing pressure to the shoulder and arm. The elbow and wrist should be supported to prevent any undue pressure to the ulnar and radial nerves. Again, neurovascular observations are a critical part of the postanesthesia assessment of these patients. The patient should be encouraged to perform active range-of-motion exercises with the hand. Ice packs or cryotherapy may be ordered to decrease edema and pain. Management of pain can include intraoperative intraarticular injection of local anesthetic, interscalene block, opioids, and or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).2 Some surgery patients benefit greatly from peripheral nerve block for prolonged postoperative analgesia (see Chapter 25 for further information on regional anesthesia).

Perianesthesia care after hip or femoral surgery

Total joint replacement or arthroplasty may be indicated in patients with painful debilitating arthritis that has failed to respond to conservative treatment over a period of time. It may also be indicated for patients with degenerative joint disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or avascular necrosis. A hip arthroplasty is a replacement of damaged or arthritic surfaces of the hip joint with materials to restore the integrity of the hip joint. The materials can be metal, plastic, or ceramic. The joint is replaced with a ball that is solidly fixed to a stem inserted into the femur and a cup that is fixed to the acetabulum, or socket. The implants are designed to create a new smoothly functioning joint that prevents painful bone-on-bone contact. A minimally invasive surgical technique is available for hip replacement. The minimally invasive technique reduces the incision from 6 to 8 inches to 3 to 4 inches and reduces the extent of soft tissue disruption in the hip. The decreased trauma to the muscles, ligaments, and tendons results in less postoperative pain. Other advantages of the minimally invasive hip replacement include shorter hospital stays, earlier mobilization, quicker rehabilitation, less blood loss, and a faster return to productivity and normal activities. The anterior approach is becoming more widely used for hip replacement because it does not split or detach muscles (see Box 37-1).1 Advantages to the anterior approach include less postoperative pain, shorter length of stay, a single and small incision, no postoperative dislocation precautions because of decreased risk of dislocation, and immediate weight bearing on the leg.1

When the patient who has had hip or femoral surgery is admitted to the PACU, nursing assessment should include pulmonary and neurovascular function, body alignment, and the amount and type of bleeding from the surgical incision. Because of long bone trauma and the often advanced age of this group of patients, these patients represent the highest risk group for postoperative orthopedic complications. Many of these patients receive spinal anesthesia and the perianesthesia nurse must monitor the level of spinal blockade close and be alert for hypotension associated with spinal anesthesia (see Chapter 25 for further information on spinal anesthesia).

The patient with posterior total hip replacement has an abduction pillow placed between the knees at all times. This position must be maintained to avoid adduction and internal rotation of the newly placed joint. The patient should not be allowed to flex the hips at a greater than 30- to 40-degree angle or to adduct the leg of the affected side. The muscle groups are weakened, and dislocation of the joint is a potential risk. If turning is necessary, the patient may be turned to the unoperated side no more than 45 degrees, with hip abduction maintained and total leg support provided. The head of the bed can be elevated no more than 45 degrees. The patient who has had an anterior total hip replacement does not require an abduction pillow, traction sling, or hip cushion to assist with positioning.1 Many of these patients use a walker and begin ambulation the same day of surgery.

An autotransfusion system or other drain with suction, such as a Hemovac, may be inserted at the operative site to facilitate the removal of blood; the color and amount should be inspected frequently. Autotransfusion is a technique that salvages red blood cells lost by the patient at the wound site and re-infuses that blood into the same patient. Autotransfusion may be used if the patient is expected to lose enough blood during the perioperative period to require transfusion and can reduce or eliminate the need for allogeneic transfusion. The patient may also receive autologous blood that was provided by the patient before surgery.9 The perianesthesia nurse should know how to operate any device that is used for drainage or autotransfusion and the hospital policies and procedures that apply (Fig. 37-4). If drainage systems are in use, the nurse should monitor the drainage and notify the surgeon for excessive volume or bright red blood.

Perianesthesia care after knee surgery

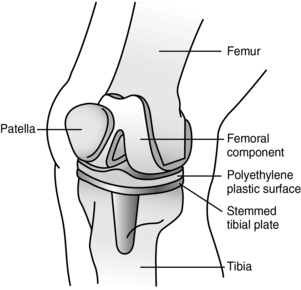

Total knee arthroplasty is a surgical procedure to replace the worn surfaces of the knee. This goal of this surgery is to relieve the patient’s complaints of chronic knee pain and instability. The replacement implants are designed to create a new, smoothly functioning joint that prevents painful bone-on-bone contact. Many different types of designs and materials are currently used in total knee replacement surgery, nearly all of which consist of three components: the femoral component (made of a highly polished strong metal), the tibial component (made of a durable plastic often held in a metal tray), and the patellar component (also plastic). Surgeons may elect to replace all or part of the knee, depending on the patient’s condition and the extent of the arthritis affecting the knee (Fig. 37-5).3 In patients with only limited knee arthritis, surgeons may choose to perform a unicompartmental or partial knee replacement. Unlike total knee replacement that involves removal of all the knee joint surfaces, a unicompartmental knee replacement replaces only one side of the knee joint. Usually knee osteoarthritis occurs first in the medial compartment of the knee, because this side of the knee bears the most weight. If the knee is otherwise healthy, a unicompartmental approach allows the outer compartment and the ligaments to remain intact, which may help the joint bend better and function more naturally. The partial knee replacement is done through a small incision, with minimal trauma to surrounding tissue. Many patients leave the hospital on the same day of or on the day after the surgery. Patients also have less postoperative pain, earlier mobilization, and less blood loss, which results in a faster return to activities of daily living. The total knee replacement is performed more frequently than the unicompartmental knee and involves replacing the opposing femorotibial joint and the patellofemoral joint.

(Modified with permission from OrthoInfo © American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, available at http://orthoinfo.aaos.org.)

Postanesthesia care of the patient who has had surgery of the knee involves observation for complications and proper knee positioning. After knee surgery, the patient may arrive in the PACU with a bulky compression dressing in place. Ice over the surgical site may be ordered to provide comfort and minimize swelling. The leg should be elevated and positioned in full extension, which can be facilitated by elevation at the ankle so that maximum extension of the leg can be accomplished. Assessments of neurovascular status should be performed frequently. Any decrease in sensation over the dorsum of the foot should be noted because it can represent compression of the peroneal nerve where it crosses the fibula at the knee. The surgeon should be notified if any neurologic or circulatory change is found, because early detection and correction prevent permanent nerve deficit or ischemic muscular injury. If the patient received a spinal anesthetic, the nurse cannot initially assess the patient’s motor function. One of the most significant complications after total knee arthroplasty is the development of DVT, possibly resulting in a PE3 (see the previous discussion of DVT and PE).

The patient with total knee replacement and the patient who has undergone extensive arthrotomy knee repair are sometimes placed in a CPM machine (Fig. 37-6). This device provides a safe method of elevation, comfort, and continuous range-of-motion to the operative knee. The CPM promotes healing by increasing circulation and movement of the knee joint. The machine should be inspected to ensure proper positioning of the limb. The flexion and extension settings of the machine should be determined by the physician and are generally 0 to 30 degrees at slow speed initially.

Perianesthesia care after spinal surgery

If the surgical procedure involves C3, C4, or C5, respiratory movements should be monitored because the diaphragm muscle is innervated by the spinal outflow from these vertebrae. The patient with this nerve deficit has a lack of diaphragmatic excursion and shortness of breath and uses the intercostal and accessory muscles in breathing. If these symptoms appear, oxygen should be administered and assistance in ventilation may be necessary.

Patients who have surgery on the spine should also be observed for bleeding from the site of the operation. The patient should be turned from side to side to help reduce stasis of fluids in the lungs. The technique for turning the spinal patient is called log rolling.2 All parts of the patient’s body should move in unison. To facilitate this action, a pillow is placed between the patient’s knees, and the knee opposite the side the patient is turned to should be flexed. The use of a draw sheet can also help to facilitate turning in one smooth motion. Pillows should be placed to support the length of the back and buttocks along with the pillow between the patient’s knees. This method of turning the patient puts the least amount of pressure on the spine. With the advent of microdisk surgery, disturbance to the stability of the spine is minimal, and these patients are generally allowed activity as desired and often go home on the first postoperative day.

Perianesthesia care after limb amputation

Patients who have had an amputation of the leg are admitted to the PACU with a dressing or a cast applied to the extremity. A cast is used to provide uniform pressure to the soft tissue, to control swelling, and to position the limb to avoid contracture (see cast care discussed previously in this chapter in the section on immobilization devices). To prevent hip contracture, elevation of the lower extremity with a soft compression dressing should be achieved by elevating the foot of the bed rather than using a pillow.2 The patient with an amputation of the arm usually has a bulky compression dressing in place. The dressing should be assessed for drainage. The extremity should be elevated, and ice can be applied to reduce postoperative edema and discomfort. Opioids should be given for pain control. Phantom limb pain should be assessed and treated with appropriate pharmacologic agents. Adequate treatment is important to reduce the risk of chronic phantom pain syndrome.2

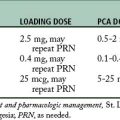

Postoperative pain management for the patient after orthopedic surgery

Orthopedic pain can be severe because of the significant muscle and skeletal tissue repair or reconstruction.10 Pain management is vital in allowing the orthopedic patient to participate in early ambulation and physical therapy; both are key components of recovery.10 Pain management for the orthopedic patient involves conventional pain protocols and can include the insertion of an epidural catheter or use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump (see Chapter 31). The patient-controlled analgesia pump administers a predetermined intravenous dose of the prescribed pain medication. The pump can be set to allow a continuous infusion of analgesic and bolus administration when the patient finds it necessary. Nonopioid analgesics such as acetaminophen, aspirin, and NSAIDs can also be used, with the possibility of gastrointestinal irritation, renal and hepatic toxic effects, and the inhibition of platelet aggregation kept in mind. Opioids such as hydromorphone, morphine, and fentanyl can be administered via IV drip, epidurally, or intrathecally to promote analgesia. Increasingly, orthopedic surgeons are using single-use systems that provide continuous delivery of local anesthetic through a small catheter inserted directly into the surgical site to decrease postoperative pain. The catheter is secured at the operative site with the dressing and with tape. Frequently, the patient is discharged home with this type of pain management. Also of note is the increased use of peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative pain management. These blocks are well tolerated by the patient and greatly increase patient satisfaction. A multimodal approach to pain management allows the lowest effective dose of each medication (opioids, NSAIDs, local anesthetics) to be administered, resulting in less side effects.10 Anticonvulsants can also be used and can produce an opioid dose-sparing effect and improve pain control.10

The perianesthesia nurse must collaborate with the surgeon and the anesthesia provider to determine an individualized plan of care to provide the patient with appropriate and effective pain management (Box 37-3).

BOX 37-3 Management of Postoperative Orthopaedic Pain: Summary of Key Points

• Screen all patients preoperatively for underlying chronic (persistent) pain.

• Establish comfort-function goals with patients preoperatively whenever possible.

• Teach the use of equipment that will be used postoperatively, such as IV PCA pumps, during the preoperative interview whenever possible.

• Ensure multimodal analgesia regardless of primary mode of therapy. The following applies to any treatment plan.

• Administer IV opioid doses to patients who have pain on admission to the PACU until a safe and satisfactory level of comfort is achieved.

• Intrathecal anesthesia or analgesia is administered by single bolus dose technique; therefore it has short duration and is used most often as part of a multimodal plan.

Copyright © Chris Pasero and Margo McCaffery, 2006. Used with permission.

Implications for practice

Patients may benefit from an educational intervention that focuses on relieving pain and anxiety and improving self-efficacy. Self-efficacy interventions such as seeking pain relief and practicing breathing relaxation techniques could result in decreased anxiety and pain. This educational intervention could be part of routine care for musculoskeletal trauma patients before surgery. Similar interventions could be applied to other patients who require orthopedic surgery.

Source: Wong EM, et al: Effectiveness of an educational intervention on levels of pain, anxiety, and self-efficacy for patients with musculoskeletal trauma, J Adv Nurs 66:1120–1121, 2010.

Summary

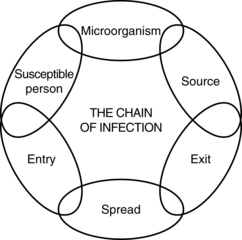

Postanesthesia care unit nurses are highly skilled to assess, plan, and care for patients as they recover from surgery and anesthesia. When caring for the patient after orthopedic surgery in the PACU, the patient must be provided with appropriate care related to the surgical treatment received for a specific musculoskeletal disorder. These procedures can vary from outpatient hand and foot surgeries to more major joint and spine surgeries. Regardless of the complexity of the surgery, the patient is susceptible to joint stiffness and skin breakdown from impaired physical mobility, neurovascular compromise from pressure on major blood vessels or nerves caused by compartmental edema or immobilization devices, infection of the surgical site, and general discomfort and pain. The PACU nurse who has a basic understanding and knowledge of orthopedic procedures and associated nursing care is able to provide the patient with safe and efficient care in the immediate postoperative period.

1. Munro CA. The perioperative nurse’s role in table-enhanced anterior total hip arthroplasty. AORN J. 2009;90(1):53–72.

2. Saufl N. Orthopedic care. Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: preprocedure, phase I and phase II PACU nursing. ed 2. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

3. Canale ST, Beaty JH. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics, ed 11. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008.

4. Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. ed 19. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.

5. Urbano FL. Homan’s sign in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis, Hospital Physician, March 2001. available at www.turner-white.com/pdf/hp_mar01_homan.pdf, January 1, 2012. Accessed

6. The Joint Commission: 2012 Hospital national patient safety goals. available at: www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2012_NPSG_HAP.pdf, January 1, 2012. Accessed

7. Kulik S. Orthopedic surgery. Stannard D, Krenzischek D. Perianesthsia nursing care: a bedside guide for safe recovery. New York: Jones & Bartlett; 2012.

8. Bowen B. Orthopedic surgery. Rothrock J, ed. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14, St. Louis: Mosby, 2011.

9. Joyce JA. Anesthesia for orthopedics and podiatry. Nagelhout JJ, Plaus KL. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4, St. Louis: Saunders, 2010.

10. Pasero C. Orthopaedic postoperative pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007;22:160–174.

Altizer L. Compartment syndrome. Orthopaedic Nurs. 2004;23:391–396.

Altizer L. Neurovascular assessment. Orthopaedic Nurs. 2004;21(4):48–50.

American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery. available at www.orthoinfo.aaos.org, January 1, 2012. Accessed

American Society for Surgery of the Hand. available at www.assh.org, June 1, 2011. Accessed

American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. available at www.asra.com, June 1, 2011. Accessed

Atlee J. Complications in anesthesia, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Barrett K. Ganong’s review of medical physiology, ed 23. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2010.

Boezzart A. Anesthesia and orthopaedic surgery. New York: McGraw Hill; 2006.

Encyclopedia of Nursing & Allied Health: Bladder ultrasound. available at: www.enotes.com/nursing-encyclopedia/bladder-ultrasound, January 1, 2012. Accessed

Fleisher LA. Anesthesia and uncommon diseases, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Hall J. Guyton & Hall’s textbook of medical physiology, ed 12. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Harvey CV. Complications. Orthopaedic Nurs. 2006;25:410–412.

Hohler SE. Looking into minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. OR Nurse. 2007;1(1):32–37.

Mamaril M, et al. Care of the orthopaedic trauma patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007;22:184–194.

Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Mulroy MF. A practical approach to regional anesthesia, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Pasero C, McCaffery M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Shugars RA, More RC. Arthroscopic hip surgery. AORN J. 2005;82(6):975–992.

Surgical Care Improvement Project Module 1: Infection prevention update. available at: www.medscape.org/viewarticle/557689, July 31, 2011. Accessed

Swank ML, Lehnert IE. Orthopedic roles in the OR for computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. AORN. 2005;82(4):631–640.

Warner C. The use of the orthopaedic perioperative autotransfusion (OrthoPAT™) system in total joint replacement surgery. Orthopaedic Nurs. 2001;20(6):29–32.