42 Care of the obstetric and gynecologic surgical patient

Cerclage Procedure: Procedure for the treatment of incompetent cervix. The McDonald procedure involves the placement of a pursestring suture on the cervix at the level of the internal os. The Shirodkar’s procedure involves placement of a fascia lata (from the thigh) or a surgical band at the level of the internal os.

Cesarean Hysterectomy: Incision of the abdomen and the uterus, extraction of the infant and the placenta, and performance of a hysterectomy.

Cesarean Section (C-Section): Delivery of an infant through an incision made in the abdominal and uterine walls.

C-Section, Classic: A midline incision between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis and an anterior incision through the uterine wall.

C-Section, Low Segment: An incision in the lower part of the uterus made after an abdominal incision.

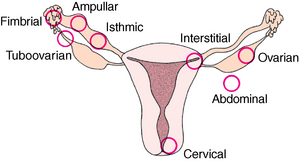

Ectopic Pregnancy: Implantation of the fertilized ovum in any site other than the upper half of the uterus.

Uterine Aspiration (Suction Curettage): Dilation of the cervix and vacuum removal of the uterine contents.

LOWER GENITAL SURGERY, VAGINAL SURGERY, ABDOMINAL SURGERY (LAPAROTOMY AND LAPAROSCOPY)

Bartholin’s Duct Cyst: A cyst that results from chronic inflammation of one of the major vestibular glands at the vaginal introitus.

Bartholinectomy: Removal of a Bartholin duct cyst.

Cervical Conization: Removal of abnormal cervical tissue via scalpel, electrosurgical current, or laser.

Colporrhaphy: Repair of the vaginal wall. May be anterior, as for cystocele repair, or posterior, as for rectocele repair or enterocele repair specifically for a vaginal prolapse.

Culdoscopy: An operative diagnostic procedure in which an incision is made into the posterior vaginal cul-de-sac, through which a tubular instrument similar to a cystoscope is inserted for the purpose of visualization of the pelvic structures, including the uterus, fallopian tubes, broad ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, rectal wall, sigmoid colon, and sometimes the small intestine. A newer technique for this procedure is transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy, which uses normal saline solution and a camera attached to a small-diameter rigid endoscope.

Cystocele: Prolapse of the bladder into the anterior vaginal wall.

Dilation of the Cervix and Curettage of the Uterus (D&C): Introduction of instruments (dilators) through the vagina into the cervical canal and scraping of the uterus with a curette for removal of substances, including blood. This procedure is used for diagnostic purposes and for treatment of conditions such as incomplete abortion, abnormal uterine bleeding, and primary dysmenorrhea.

Enterocele: Defect in the continuity of the endopelvic fascia most commonly seen after hysterectomy when the anterior pubic fascia is not attached to the Denonvilliers fascia.

Hysterectomy: Removal of the uterus; can be vaginal (with or without laparoscopic assistance) or abdominal (via laparotomy).

Hysteroscopy: Direct visualization of the canal of the uterine cervix and cavity of the uterus with an endoscope called a hysteroscope.

Procidentia: Herniation of the uterus beyond the introitus.

Prolapse of the Uterus: Downward displacement of the uterus. Vaginal hysterectomy is often recommended for a prolapsed uterus when childbearing is no longer desired or when marked prolapse is present.

Rectocele: Prolapse of the rectum into the posterior vaginal wall.

Trachelorrhaphy: Removal of torn surfaces of the anterior and posterior cervical lips and reconstruction of the cervical canal.

Urethrocele: Prolapse of the urethra into the anterior vaginal wall.

Vaginal Plastic Operation (Anterior and Posterior Repair): Reconstruction of the vaginal walls (colporrhaphy), the pelvic floor, and the muscles and fascia of the rectum, urethra, bladder, and perineum. Used to correct a cystocele or rectocele, restore the bladder to its normal position, and strengthen the vagina and the pelvic floor.

Abdominal myomectomy: Removal of leiomyomas (fibroids) through a large or small incision; if this is done laparoscopically, then the abdominal cavity is visualized through a small incision, usually at the umbilicus after the establishment of a pneumoperitoneum. A video camera is attached to the eye piece of the laparoscope so that the surgeon and team can visualize the procedure while watching a video monitor; this provides a magnified view of the pelvis. If the robot is used, it is often set up after the umbilical trocar is in position.

Oophorectomy: Removal of an ovary.

Oophorocystectomy: Removal of an ovarian cyst.

Radical Hysterectomy: Removal of the uterus, the uterosacral and uterovesical ligaments, the upper third of the vagina, and all the peritoneum. This may or may not include removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Salpingectomy: Excision of the fallopian tube.

Salpingo-Oophorectomy: Removal of the fallopian tube and the associated ovary.

Salpingostomy (Tubal Plasty): Repair and opening of the fallopian tube to establish patency. This is often done in the case of a hydrosalpinx. Tubal plasty or tubal reanastomosis is used for removal of an obstructed portion of the tube and reconnection of each normal end of the tube after the obstruction has been removed to establish patency. Tubal reanastomosis increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Because the success rates of in vitro fertilization are so good, this procedure is seldom done anymore.

Total Abdominal Hysterectomy: Removal of the uterus, including the cervix (with or without the adnexa which refers to the tube and/or ovary), through an abdominal incision. Various types of hysterectomy include the following if done laparoscopically:

LTH or TLH: Laparoscopic total hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy; the uterus is removed laparoscopically and the vaginal cuff is sutured laparoscopically.

LSH: Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy; the uterus is removed laparoscopically and the cervix remains. This is thought to be the hysterectomy with the least morbidity and the quickest recovery for the patient postoperatively.

LAVH: Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy; the uterus is reached laparoscopically and removed vaginally. The vaginal cuff is sutured vaginally.

NOTE: If a robot is used, the robot must be disconnected for any tissue to be removed. One of the main reasons some physicians choose to use the robot is because they find suturing laparoscopically much easier with the robot.

Tubal Ligation: Interruption of fallopian tube continuity, which results in sterilization; this is most commonly done laparoscopically. The fallopian tube is cauterized or ligated, a clip is placed, or the tube is partially excised. Reversal procedures can be attempted with tubal reanastomosis using microsurgery; however, this is seldom done because the success rate of IVF is so high.

Traditionally, surgery on organs of reproduction usually involved an adult patient. However, in most recent years as girls reach puberty at earlier ages, it is becoming more frequent for young girls in their teens to have laparoscopic surgery for conditions such as endometriosis.1 In addition, the perianesthesia nurse may encounter pediatric or adolescent female patients who undergo gynecologic surgery for repair or correction of congenital or traumatic deformities or incapacitating pelvic pain from causes such as endometriosis, ovarian cyst, or appendicitis. Surgery on the female genitalia may be conveniently divided into three major categories: obstetric, lower genital and vaginal, and abdominal gynecologic surgery. Abdominal surgery is then subdivided into either what used to be referred to as traditional surgery in the form of a laparotomy, mini-laparotomy (could include hand assisted surgery through a mini type laparotomy incision), or into the category of operative laparoscopy (typically two or three small incisions or robotic surgery, which may include four to seven incisions). The area of operative laparoscopy in gynecologic surgery has expanded and includes the majority of benign gynecologic surgery. However, there are still a great number of laparotomies currently performed. Many surgeons who previously have not felt comfortable performing laparoscopic procedures are now doing so with the aid of the robot. There is much debate among gynecologists as to whether the learning curve is shorter with the use of the robot. Whether or not that is the case, the bigger questions are “Is the cost of the robot warranted?” and “With proper training, can these same procedures be done just as effectively without the robot?” The perianesthesia nurse must be aware of how the care of the patient differs with these various approaches.

Obstetric surgery

Care after specific procedures

Cesarean section

Cesarean sections are indicated for dystocia (usually caused by cephalopelvic disproportion); antepartum bleeding; some toxemic conditions; certain medical complications, especially diabetes mellitus; and previous cesarean section. The low-segment cesarean section is usually the procedure of choice. Anesthesia may be general inhalation, spinal, or local infiltration of the operative field. Postoperative care after cesarean section includes all care rendered to a patient who undergoes abdominal surgery and postpartum care.

On admission to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), a report is given by the circulating nurse who transports the patient with the anesthesia provider to the PACU area. The patient’s vital signs should be monitored regularly in keeping with the PACU guidelines in the facility. As soon as condition permits, the patient can assume any position of comfort. Oxygen should be delivered and monitored with the use of pulse oximetry.2

Ectopic pregnancy

Faulty implantation of the ovum can take place in the fallopian tube (in approximately 98% of all ectopic pregnancies), in the ovary, in any part of the abdominal cavity, or in the uterine cervix (Fig. 42-1). Until recently, the treatment of choice for an ectopic pregnancy in the fallopian tube was laparoscopy (or laparotomy) with removal of the ectopic pregnancy and most often with preservation of the fallopian tube. In cases in which bleeding cannot be controlled or the physician believes that the fallopian tube poses too much of a risk for the patient, removal of the fallopian tube at the time of surgery may be necessary. Obviously the patient must give proper consent before surgery, and all these possibilities are thoroughly discussed between the surgeon and the patient. More recently, however, patients with the early diagnosis of an unruptured ectopic pregnancy can receive intravenous methotrexate and not undergo surgery. Regardless of the treatment, these patients must have proper follow-up with their physicians to ensure successful treatment, which involves follow-up quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin studies and possibly ultrasound scans as well.

Cerclage procedures

On admission to the PACU, hospital guidelines are followed regarding patient admission to the PACU and care of the patient (see Chapters 27 and 28). Oxygen should be administered and weaned with pulse oximetry. Food and fluids can be resumed as soon as the patient is conscious and the laryngeal reflexes have returned. A perineal pad should be kept in place. Only a minimal amount of bloody spotting is normal. Pain should be minimal and easily controlled with a simple analgesic, such as acetaminophen. Any gross vaginal bleeding or abdominal cramping should be reported to the surgeon, because this procedure may induce labor and expulsion of the uterine contents. The surgeon may order an external fetal monitor to assess the presence of uterine contractions and fetal heart tones. If labor begins, the suture must be removed immediately.

Gynecologic surgery

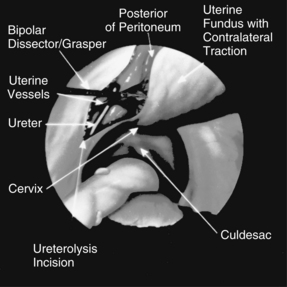

Certain problems are inherent in gynecologic disease processes and the surgical procedures that deal with them. Because of prolonged or heavy menstrual periods, the patient may be more chronically anemic than even the peripheral blood indices indicate. Moreover, large amounts of blood may have accumulated within the pelvic organs at the time of the operation and may not be reflected in the external blood loss. Although the procedures are elective, many gynecologic operations are associated with significant blood loss, depending on the approach taken. This can be affected by the patient’s age (more if she is premenopausal), a larger uterus, and large fibroids. One of the potential benefits of a well-trained laparoscopic team is a decrease in intraoperative complications and blood loss and a significant reduction in postoperative morbidity. For example, in the case of a hysterectomy or large fibroids in a premenopausal woman, the uterine vessels are large, vascular pedicles that need to be thoroughly coagulated to ensure hemostasis during surgery. For this reason, regardless of the approach (laparoscopy with or without a robot, vaginal, or laparotomy), these vessels must be identified and coagulated or ligated effectively. In addition, because of the proximity of the female organs to the urinary tract, great care must be taken during surgery to identify the ureters and bladder and provide proper follow-up during the observation period after surgery to ensure the integrity of this system. If there is any question of this, a cystoscopy should be done upon the conclusion of the surgery. In addition to overall assessment and general care of these patients, the perianesthesia nurse should direct specific attention toward the patient’s cardiovascular status, renal function, and fluid balance.3

Laparoscopy

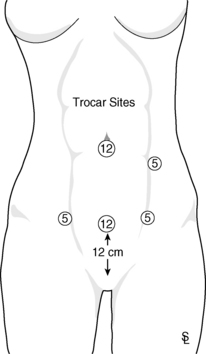

Operative laparoscopy commonly is performed as outpatient surgery for treatment of benign gynecologic problems and may involve advanced operative laparoscopic procedures for more significant problems that involve the pelvic organs. A small incision (approximately 1 cm) is made at the subumbilical site for insertion of the primary trocar (typically 10 to 12 mm in diameter), which houses the laparoscope with attached video camera for visualization of the pelvis (Fig. 42-2). The entry into the pelvic cavity can be done various ways; one of which includes open laparoscopy, particularly for patients who have had multiple previous surgeries to protect against injuring the bowel. When a patient has had multiple previous surgeries, the bowel is more likely to be adhered to the abdominal wall and oftentimes thought to be a safer way to enter. After pneumoperitoneum is established, the surgeon can visualize the organs within the peritoneum. The video camera enables the surgeon, first assistant, scrub technician, and entire team to view the procedure on the video monitor (Fig. 42-3). The video camera provides excellent resolution and visualization of the pelvis.

Advances in digital technology with high-definition (HD) cameras and monitors provide better resolution than ever before (Fig. 42-4). The surgeon is able to operate from HD monitors with instruments that are typically 5 mm in diameter (sometimes the instruments are as small as 3 mm in diameter or as large as 12 mm in diameter, depending on the procedure). In addition, an angled laparoscope can be used for improved visualization in the case of a large uterus. If the robot is to be used, it is connected after the trocars have been placed. The robot offers three-dimensional visualization that some find appealing. The surgeon sits at a console and is able to maneuver the instrumentation from that location while the surgical assistant is at the patient’s side and using instrumentation such as suction and irrigation. In addition, a surgical technologist is typically present between the patient’s legs (similar to laparoscopy without the robot) to manipulate the uterus with a uterine manipulator. In addition to the expense of the robot, there can be a significant amount of time required for the robot to be connected and disconnected. This includes the sterile draping of the arms of the robot. If an emergency arises with bleeding that cannot be controlled, the robot has to quickly be disengaged so that traditional surgery can quickly be initiated. For teaching purposes in particular, it is now possible to get a robot with two consoles so that the surgeon may have the student surgeon (resident or fellow) at the secondary console to work and receive instruction.

The surgeon examines the ovaries, fallopian tubes, pelvic side walls, uterosacral ligaments, bowel, appendix, peritoneum, anterior and posterior cul de sacs, and uterus after placement of the second and third incisions suprapubically in the right and left lower quadrants of the abdomen (this houses the ancillary instrumentation). If additional instrumentation is needed, a fourth incision may be made along the midsuprapubic area as well. During operative laparoscopy, the surgeon may differentially diagnose pelvic inflammatory disease or perform relatively simple procedures, such as aspiration of an ovarian cyst, lysis of adhesions, tissue biopsy, and tubal ligation. In addition, more advanced laparoscopic procedures may be done, including extensive lysis of adhesions, excision of mild, moderate or severe endometriosis, myomectomy, hysterectomy (laparoscopic total hysterectomy or laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy), salpingectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, removal of an ovarian remnant, ureterolysis, paravaginal repair or Burch procedures, repair of pelvic floor relaxation including laparoscopic sacral colpopexy with nonabsorbable mesh appendectomy, fibrinolysis, and tubal reanastomosis (Fig. 42-5). Various types of laparoscopic hysterectomy include laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, in which the cervix is preserved, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH), and total laparoscopic hysterectomy. It is important to note that not all energy sources can be used with the robot, such as certain types of lasers and electrosurgery devices. In cases of severe endometriosis in which there is significant bowel involvement, a general surgeon may be called to do a laparoscopic bowel resection with the gynecologist. These surgeries may occur in patients with severe endometriosis and bowel symptoms and who have had a complete bowel preparation before surgery. The general surgeon, who is part of the endometriosis team, is on standby for that type of procedure. PACU needs to be aware of any special needs postoperatively for patients undergoing either a laparoscopic bowel resection or a laparoscopic cystotomy and repair of the bladder for extensive invasion of these tissues with endometriosis. In regard to any type of bladder repair, it is common for the urinary catheter to be left in place for at least 7 to 10 days. With bowel surgery, the patients are generally kept inpatient for 3 to 4 days until bowel function returns. The diet generally is very limited, beginning with ice chips, followed by clear liquids, clear fluids, and then advance to a soft diet. In most cases, these patients no longer require a colostomy or a suprapubic urinary catheter. Always notify the surgeon if there is a significant amount of bleeding from any orifice. It is common for patients to have a pinkish urine output after cystoscopy. Often these patients have at least a mild form of interstitial cystitis. If there is any blood in the urine when the patient is brought to the PACU, the circulating nurse should communicate that information in the report.

A follow-up phone call to the patient within 24 to 48 hours is recommended. Special care for the patient who undergoes outpatient surgery is outlined in Chapter 46.

Lower genital and vaginal surgery

From Yeung P, et al: Complete laparoscopic excision of endometriosis in teenagers: is postoperative hormonal suppression necessary? Fertil Steril 95:6:1909−1912, 2011.

• Baldy-Webster procedure: Shortening of the round ligaments and changing of the direction of their pull by attaching them to the back of the uterus

• Fothergill-Hunter procedure: Complete repair of the vaginal wall (enterocele defect), from above downward toward the vulva, to correct faulty supportive structures of the pelvic floor; various defects commonly referred to as vaginal defect (enterocele repair), protrusion of the bladder (cystocele repair), or protrusion of the rectum (rectocele repair) and prolapse of the vaginal walls (paravaginal repair); generally a combination and not an isolated repair, which is why a urogynecologist is often the best person to most thoroughly make these repairs because there is so much overlap and it is important to evaluate the woman’s entire pelvic floor for optimal success with the repairs

• Gilliam procedure: Shortening of the round ligaments by attaching them to the abdominal wall

• Le Fort operation (colpocleisis): Closure of the vagina with approximation of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls with or without attendant vaginal hysterectomy

• Radical vulvectomy: Abdominal and perineal dissection of the superficial and deep inguinal nodes and portions of the saphenous veins, reconstruction of the vaginal walls and pelvic floor, and closure of the abdominal wounds

• Vulvectomy: Removal of the labia majora, labia minora, and possibly the clitoris and perianal area, with a Z-plasty closure; used in treatment of leukoplakia vulva, carcinoma in situ of the vulva, and Paget disease of the vulva

Other vaginal surgical procedures include fistula repairs, correction of urinary stress incontinence (various sling procedures with nonabsorbable transobturator tape), and vaginal reconstruction to repair congenital or acquired defects developed during childbirth. Many of the pelvic floor repair procedures can be done laparoscopically if the surgeon is comfortable with laparoscopic suturing and is a well-trained laparoscopist. Currently there is a great amount of debate over the types of mesh being used in the body. In particular, mesh that is used for gynecologic pelvic organ prolapse procedures is under investigation because of infections and mesh erosion, which can cause subsequent pain months or years after surgery. In the past it was thought that the type of mesh and the pore size were the key factors; however, this is being discussed again. Patients with severe prolapse need some type of graft, and it is unclear what the eventual reality will be on this issue. Most importantly, patients must be sure to stay abreast of the research on this topic. Regardless of the type of graft that is used, a well-trained laparoscopist is required to do these procedures. Many gynecologists use the robot because they are not comfortable suturing laparoscopically. Other surgeons believe that the time and expense is unnecessary if the surgeon takes the time for proper training. In addition, many gynecologists believe that they can do the surgery more effectively and efficiently without the robot. Operative laparoscopy typically requires three to four incision sites, and the robotic laparoscopy may require four to seven incisions. In addition, there are single puncture devices that may be used at the umbilicus without the robot, and those are also being developed to be used with the robot. The debate continues about whether the surgery can be done effectively with one larger single site incision at the umbilicus. During a time when health costs are out of control, cost of instrumentation and equipment and length of surgery are important, and the question remains, does the robot offer advantages over advanced operative laparoscopy by a well trained, experienced laparoscopist and team?

General perianesthesia care

Pain must be carefully evaluated and may be alleviated with appropriate analgesics. Abdominal cramping is common after gynecologic surgery. For these patients, relaxation exercises are often helpful if they have been learned before surgery. Warm blankets over the abdomen can also aid in relaxation. Because the patient is often drowsy from the anesthesia, coaching is needed, especially during the first hour. If cramping is not relieved with relaxation exercises, analgesics, or other comfort measures, the surgeon should be notified because this may indicate a perforated uterus or more severe problem. After removal of tumors or cysts from the vaginal area, ice can be applied to reduce edema and provide comfort.4

Abdominal gynecologic surgery

Abdominal gynecologic surgery can be performed alone or in conjunction with vaginal surgery.

General postoperative care

Postoperative care after abdominal gynecologic surgery involves all the care and considerations rendered to the patient who undergoes any type of abdominal surgery. Anesthesia is most often general.5 Overall assessment of the patient, with special emphasis on the cardiovascular status, should be undertaken as soon as the patient is admitted to the PACU.

After total abdominal hysterectomy or major abdominal procedures, the patient is usually not given anything orally until peristalsis has returned and nausea has subsided. Intake is supplied with intravenous fluids. Occasionally the patient is admitted to the PACU with a nasogastric tube to prevent abdominal distention. If abdominal distention develops, nasogastric and rectal tubes can be used to relieve it.6

A urinary catheter is often in place, and its patency must be ensured. The perianesthesia nurse should accurately document the amount of urinary output and the presence of blood. A possible complication of hysterectomy is accidental perforation or ligation of a ureter. Inadvertent injury to the bladder wall or the bowel may also occur.

After laparoscopic surgery, patients should begin to feel significantly better within 48 to 72 hours. If they still have a great deal of discomfort or if they begin to feel better and then start to feel much worse a couple of days later, the surgeon should be notified immediately. This condition could indicate a postoperative complication that could involve the development of a hematoma, an infection, or an injury to the bowel, bladder, or ureter. A bowel injury often does not present itself until the patient has gone home. The injury could be serious, and the physician must identify and recognize it as soon as possible. All these criteria should be outlined in the written discharge instructions. Many facilities that discharge patients within 24 hours after surgery follow up by calling patients within 24 to 48 hours to see how they are doing. Usually this call is a courtesy call. If a problem is found, the patient is generally encouraged to contact the physician. If the patient ever has shortness of breath, severe pain, or bleeding heavier than a period, they should contact their physician immediately or go to the nearest emergency room.7

1. Yeung P, et al. Complete laparoscopic excision of endometriosis in teenagers: is postoperative hormonal suppression necessary. Fertility and Sterility.2011;95(6):1909–1912.

2. McEwen DR. Gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Rothrock J., ed. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 13, St. Louis: Mosby, 2007.

3. Adolph A, et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy for the large uterus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(2):170–174.

4. Baughman VL, et al. Anesthesiology and critical care drug handbook, ed 9. Ohio: Lexicomp; 2009.

5. Lyons TL, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy, 2005. available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/laparoscopic-approach-to-hysterectomy, August 28, 2011. Accessed

6. Winer WK. Core curriculum for the RN first assistant, section VIII: gynecology and obstetrics. AORN; 2005:197–212.

7. Winer WK, Seifert PC. Advances in minimally invasive gynecology, Perioperative Nursing Clinics 1(4). 2006:305–380.