7 Care of the Elderly

Blackouts

What should you ascertain from the history?

Epilepsy in the elderly

• Focal fits or a focal origin of generalised seizures are common in the elderly (accounting for 80% of fits in this age group).

• Post-ictal confusion, headache and focal signs (Todd’s paresis) are common.

• 35% to 50% of fits in the elderly are caused by vascular disease.

• 20% of patients with stroke have seizures within the first year.

• Elderly persons are more susceptible to pharmacological causes of fits, e.g. neuroleptics, tricyclics, and to alcohol withdrawal.

• An EEG can be useful but a normal or non-diagnostic EEG does not rule out epilepsy.

• Don’t forget hypoglycaemia as a cause of fits.

• Anti-convulsant drugs should be started after the first fit if a vascular or structural cause is suspected.

• Pallor suggests cardiac cause.

• Tonic–clonic contractions or incontinence suggest epilepsy.

• Was there a history of head turning or tight neckwear? This suggests carotid sinus syndrome.

• Was there a period of drowsiness after blackout? This suggests epilepsy but might also occur in cardiac causes.

Investigations

• FBC, U&Es, glucose, TFTs, Ca2+

• 24-hour tape if ECG abnormal or history suggestive of cardiac cause

• If history suggests epilepsy: EEG, and/or CT scan

• Specialist intervention: carotid sinus massage – undertaken if carotid sinus syndrome suspected (Note: contraindications for massage include presence of carotid bruit or history of carotid territory neurological events)

Cardiovascular causes of blackouts

• Arrhythmias (brady- or tachy-) can be difficult to diagnose and sometimes require repeated 24-h tapes or 2–3-week ‘event recorders’ (see p. 278).

• Myocardial infarction: can be pain free in older people.

• Aortic stenosis: typically causes exertional syncope, also shortness of breath on exertion and angina.

• Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: diagnosed on echocardiogram.

• Carotid sinus syndrome is an underdiagnosed cause of unexplained blackouts. It is caused by an exaggerated response of baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and requires specialist investigation by carotid sinus massage with close observation. There are three variants. The cardioinhibitory variant is diagnosed by > 3-s asystole on massage. The vasopressor variant is diagnosed by a 50-mmHg drop in blood pressure or systolic blood pressure drop to < 90 mmHg. Thirdly, up to one-third of cases are mixed.

• Vasovagal syncope: occasionally presents for the first time in older people. Consider if there is a long history of ‘funny turns’.

Falls in the elderly

What questions should you ask?

• What was he doing when he fell, e.g. was there a postural element?

• What does he remember about the fall?

• What happened immediately before the fall?

• Were there any preceding symptoms?

• Were there any physical hazards, e.g. wet floor, carpet edge?

These features can help distinguish pathological causes (intrinsic) from those with a major external factor (extrinsic), although in practice most falls are multi-factorial. Falls or ‘collapse’ can be seen as a final common pathway for many diseases common in the elderly.

Orthostatic hypotension

This is defined as a > 20-mmHg drop in systolic BP on standing or during head-up tilt:

• Common in elderly: occurs in up to 30% of healthy older people and it is not clear why some develop symptoms.

• ‘Physiological’ changes in elderly: decreased baroreceptor sensitivity increases risk of postural hypotension.

• ‘Pathological’ changes: e.g. sepsis with vasodilatation; poor LV function; neurological disease affecting reflex pathways.

• Pharmacological causes: beta blockers, vasodilators, anti-parkinsonian drugs, sedatives, neuroleptics, diuretics.

Investigations of falls

• BP and heart rate measurement with patient lying flat, with patient standing upright or at 45° on tilt table after 1, 3 and 5 min.

• FBC for evidence of infection, anaemia.

• U&Es, creatinine for evidence of dehydration, renal impairment (eGFR is calculated).

• Blood glucose for hypo-/hyperglycaemia.

• Thyroid function tests for subclinical hypothyroidism.

• ECG for ischaemia, arrhythmias, silent MI.

• Heart beat monitoring (beat-to-beat variation) for autonomic neuropathy.

Delirium (see p. 515)

Delirium in the elderly

As a condition (syndrome) it is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Diagnosis

Confusional assessment method (CAM) criteria

1. Acute onset + fluctuating course: this history is usually obtained from the family/carer or from the nurse caring for a patient already in hospital.

2. Inattention: is the patient easily distractible or does he/she have difficulty keeping track of what is being said?

3. Disorganised thinking: is the patient incoherent? Is the conversation irrelevant?

4. Altered level of consciousness: the patient might be hyperactive, hypoactive/lethargic or semi-conscious.

Remember

• One in four patients with delirium are hypoactive

• Although history/observations can confirm the presence of CAM features, it is also useful to assess the patient’s cognitive functioning using serial mental test scores, e.g. Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) (Table 7.1). Other tests using questions on: orientation (e.g. time, place, date), registration (naming objects), attention and calculation (simple arithmetic), recall (previously mentioned objects) and language (understanding commands) can be used.

Causes

For causes, remember the mnemonic delirium and think of common conditions:

D drugs: side effects, toxicity of drugs, e.g. hypotensives, sedatives

E electrolyte/endocrine disturbance, e.g. hyponatraemia, hypernatraemia, hypothyroidism

L lack of drugs: withdrawal of drugs

I infections, e.g. pneumonia, cellulitis

R reduced sensory input, e.g. visual impairment

I intracranial: TIAs, epilepsy

How would you manage a patient with delirium?

• Treat cause(s) of delirium. Review present drug therapy.

• Environmental measures and general support: fluids/nutrition; bladder/bowel care + environment (nurse in quiet, dimly lit room if possible), providing reassurance and reorientation.

• Pharmacological management: only appropriate if general supportive measures are not adequate to reduce patient’s distress and if there is danger to patient. Drugs of choice:

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

Inovye SK. Delirium in the older persons. NEJM. 2006;354:1157–1185.

Young J, Inovye SK. Delirium in older people. BMJ. 2007;334:824–826.

Dementia

Definition.

• The capacity to solve problems of day-to-day living.

• The performance of learned perceptuomotor skills.

• The correct use of social skills.

• The control of emotional reactions in the absence of gross clouding of consciousness.

• Dementia is often irreversible and progressive, and has a number of causes.

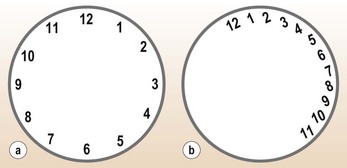

• Assessment: this is performed using the 10-point Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT; Table 7.1), or Clock-drawing test (Fig. 7.1).

• Although screening tests are useful in demonstrating the presence of deficits in cognition, they cannot be used for making the diagnosis of dementia or identifying the underlying cause. This requires imaging (CT or MRI scan) and, in some patients, assessment by a clinical psychologist and/or a psychiatrist. A history of progressive decline in memory or cognition over 6 months is significant.

Causes

The common causes of dementia include Alzheimer’s disease, multi-infarct dementia, Lewy body dementia and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, but other conditions can produce a dementia-like syndrome (Table 7.2) and p. 523.

Table 7.2 Examples of treatable causes of dementia-like syndrome (see also p. 523)

Management

• Alzheimer’s disease (AD): although there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, research on acetylcholine esterase inhibitors has shown that in selected patients with mild to moderate AD the decline can be slowed down. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced a guidance on use of donepezil, rivastigmine, memantine and galantamine in patients with mild to moderate AD by specialists. Other agents/drugs that have some benefit to patients with AD include vitamin E and Ginkgo biloba extract.

• Multi-infarct dementia: treat the risk factors, such as hypertension. Aspirin also has a role in preventing further strokes. Ginkgo biloba (120–240 mg daily) can also help.

• As dementia progresses, the management focus changes to care provision for patients plus support for carers.

• Lewy body dementia: avoid anti-psychotics as they can increase confusion. Some of these patients respond to acetylcholine esterase inhibitors.

Depression

Depression is common in old age (see also p. 528). Community studies have revealed a prevalence of 11.3% for depressive symptoms and 3% for depression in the UK. Studies of elderly hospital inpatients have shown that up to 33% have depression. It is common in the elderly with chronic physical illnesses such as stroke, and it can also be the presentation of an occult physical illness such as hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia or carcinoma of the lung. Physical illness is the biggest risk factor for depression in old age.

Case history

Examination showed no abnormality apart from slight residual neurological signs from his CVA.

Assessment

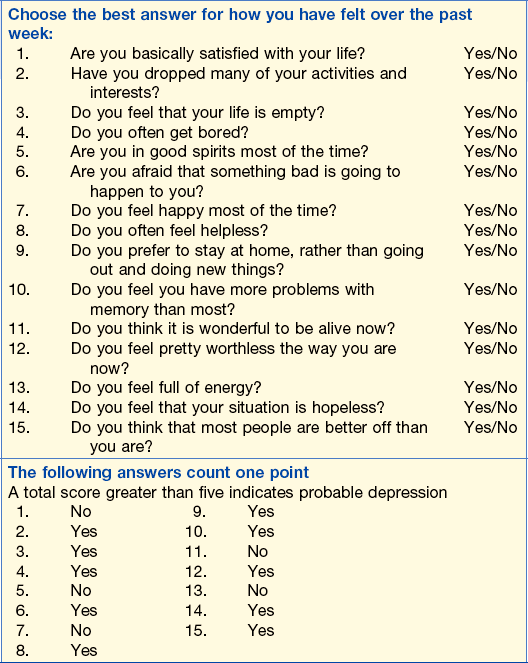

• Geriatric depression scale (Table 7.3) as a screening test. The Geriatric Depression Scale (shorter version) is a reliable and valid screening instrument of depression in the elderly. A score greater than 5 indicates probable depression.

• Physical examination and investigations to detect/exclude physical causes of depression, such as hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia, malignancy. In a patient with a normal physical examination it is recommended that FBC, U&Es, LFTs, vitamin B12, Ca2+,  TFTs and chest X-ray are performed.

TFTs and chest X-ray are performed.

In this patient, these blood tests and the CXR showed no abnormality.

Table 7.3 Geriatric Depression Scale

From Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clinical Gerontologist 1986; 5: 165–173.

Management

• Citalopram: a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) 8–32 mg daily.

• Mirtazapine: a pre-synaptic alpha-2 antagonist is particularly useful in patients with poor appetite – 15 mg daily, increased according to response to 45 mg daily.

• Venlafaxine: a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, 75–150 mg daily.

Severely depressed patients with or without suicidal ideation need urgent referral to a psychiatrist for further assessment.

Non-specific presentation of illness in the elderly

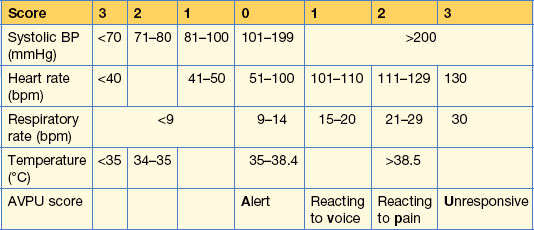

These problems are highlighted in the following case. MEWS (Table 7.4) is a simple physiological scoring system that can be used at the bedside in a medical admission unit. It identifies patients at risk of deterioration and who may require more specialised care.

Case history (1)

On arrival in hospital Mr S was very confused and unable to give a detailed history. His abbreviated mental test (AMT) score (see Table 7.1) was 3 out of 10.

It was not clear how long he had been confused or how mobile he had been before these problems.

Management

Aspirin 300 mg chewed with clopidogrel 300 mg oral gel were given. He was assessed urgently by the cardiac team who felt that despite his age he should be treated urgently with fibrinolytic therapy (p. 286). He responded well, with a fall in the ST segment to normal, without any complications of treatment.

Appropriate assessment scales

• Barthel Index: for activities of daily living (ADL) (Table 7.5).

• Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE): cognitive screening test for dementia and delirium.

• Geriatric Depression Scale: screening instrument test for depression (see Table 7.3).

• Waterlow Score: for risk quantification for pressure ulcers (Table 7.6).

• Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale: for quality of life (Table 7.7); provides a multi-dimensional approach to assessing the psychological state of older people, i.e. well-being/life satisfaction/quality of life.

Other scales, e.g. Braden, Walsall and Maelor are also available.

| Item | Categories |

|---|---|

| Bowels | 0 = incontinent (or needs to be given an enema) |

| 1 = occasional accident (once per week) | |

| 2 = continent | |

| Bladder | 0 = incontinent/catheterised, unable to manage |

| 1 = occasional accident (max. once every 24 h) | |

| 2 = continent (for over 7 days) | |

| Grooming | 0 = needs help with personal care |

| 1 = independent face/hair/teeth/shaving (implements provided) | |

| Toilet use | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = needs some help but can do something alone | |

| 2 = independent (on and off, dressing, wiping) | |

| Feeding | 0 = unable |

| 1 = needs help cutting, spreading butter, etc. | |

| 2 = independent (food provided in reach) | |

| Transfer | 0 = unable – no sitting balance |

| 1 = major help (one or two people, physical), can sit | |

| 2 = minor help (verbal or physical) | |

| 3 = independent | |

| Mobility | 0 = immobile |

| 1 = wheelchair independent (includes corners) | |

| 2 = walks with help of one (verbal/physical) | |

| 3 = independent (may use any aid, e.g. stick) | |

| Dressing | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = needs help, does about half unaided | |

| 2 = independent, includes buttons, zips, shoes | |

| Stairs | 0 = unable |

| 1 = needs help, (verbal, physical) carrying aid | |

| 2 = independent | |

| Bathing | 0 = dependent |

| 1 = independent (may use shower) |

Table 7.7 The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale

| High morale response | Low morale response | |

|---|---|---|

| Do little things bother you more this year? | No | Yes |

| Do you sometimes worry so much that you can’t sleep? | No | Yes |

| Are you afraid of a lot of things? | No | Yes |

| Do you get mad more than you used to? | No | Yes |

| Do you take things hard? | No | Yes |

| Do you get upset easily? | No | Yes |

| Do things keep getting worse as you get older? | No | Yes |

| Do you have as much pep as you had last year? | No | Yes |

| Do you feel that as you get older you are less useful? | No | Yes |

| As you get older, are things … than you thought? | Better | Worse or same |

| Are you as happy now as you were when you were younger? | No | Yes |

| How much do you feel lonely? | Not much | A lot |

| Do you see enough of your friends and relatives? | Yes | No |

| Do you sometimes feel that life isn’t worth living? | No | Yes |

| Do you have a lot to be sad about? | No | Yes |

| Is life hard much of the time? | No | Yes |

| How satisfied are you with your life today? | Satisfied | Not satisfied |

References

Lawton MP. The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale: a revision. Journal of Gerontology 1975; 30: 85–89.

Royal College of Physicians. Report of a joint workshop with the Royal College of Physicians and the British Geriatrics Society standardised assessment scales for elderly people. RCP, 1992, London.

Stroke

Typical signs of a stroke

The typical signs of a stroke are listed in Table 7.8.

Table 7.8 Clinical deficits associated with different vascular territories of the brain

| Anatomical location | Common neurological deficits |

|---|---|

| Left middle cerebral artery | Right-sided weakness involving face and arm>leg with expressive, receptive or mixed dysphasia. |

| Right middle cerebral artery | Left-sided weakness, face and arm>leg, visual and/or sensory neglect or inattention of left side, denial of disability (anosognosia). |

| Lateral medulla (posterior inferior cerebellar artery and/or parent vertebral artery) | Ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome, Xth nerve palsy (due to infarction of nucleus ambiguus), facial sensory loss (trigeminal nerve), limb ataxia with contralateral spinothalamic sensory loss. Typically, patients are vertiginous and unable to feed by mouth due (mainly) to failure of laryngeal closure during swallowing and ineffective coughing. Cervical radiculopathies may occur due to involvement of radicular branches of the vertebral artery. |

| Posterior cerebral artery | Homonymous hemianopia with variable additional deficits due to involvement of parietal and/or temporal lobe. |

| Internal capsule | Motor, sensory or sensorimotor loss, involving face, arm and leg to a roughly similar extent. There may be profound dysarthria due to involvement of corticobulbar fibres but the patient should not be dysphasic or have other cortical type deficits such as dyslexia or dysgraphia. |

| Bilateral paramedian thalamus (30% of the population have a single common arterial stem supplying the medial aspect of both thalami) | Coma or disturbed vigilance at presentation, ophthalmoplegia (internal and/or external) ataxia and memory impairment. Some patients require ventilation. |

| Carotid artery dissection | Ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome due to compression of the sympathetic plexus around the carotid artery; the same process can also affect the lower cranial nerves (Xth and XIIth most obvious clinically) in the carotid sheath, or the VIth nerve in the cavernous sinus. If ipsilateral cerebral infarction follows (due to hypoperfusion or embolisation) the clinical picture can minic a brainstem event; in this way, carotid artery dissection can mimic vertebral artery dissection. |

Is your diagnosis of a stroke correct?

Unusual symptoms and signs should make you question the diagnosis, e.g.:

Examples of misdiagnosis

Clinical problems associated with a stroke (Table 7.8)

The neurological deficit

Early management of a stroke

• Thrombolytic treatment with IV alteplase (tPA) (p. 286) needs to be given in <  h (ideal 90 min) of onset of stroke, haemorrhage having been excluded on scanning.

h (ideal 90 min) of onset of stroke, haemorrhage having been excluded on scanning.

• Aspirin: 300 mg and clopidrogel 75 mg after CT scanning (to rule out haemorrhage), if fibrinolysis is not being used.

• Hydration and/or feeding: early NG or PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastroscopy) feeding improves outcome in stroke patients who have unsafe swallowing (see below).

• Treatment of hyperglycaemia with insulin regimen initially.

• Paracetamol for pyrexia: if present.

• Prevention of complications:

• Rapid treatment of infection (most commonly chest and urinary tract).

• Hypertension: BP often rises in acute stroke but usually settles. Lowering of BP is only necessary in the early stage for severe hypertension. Persistently raised BP requires treatment for its secondary prevention benefits (see below).

• Support and interventions for the patient and family: stroke is a major life event and both the patient and family need information and support.

Dysphagia and aspiration

If the patient’s conscious level is impaired, do not assess the swallow until it improves.

How would you investigate and treat this patient?

The National Stroke Guidelines state that fibrinolytic therapy be commenced; fibrinolytic therapy is indicated in patients with a cerebral infarct due to a thrombus which occurred less than 4.5 hours ago (see p. 476). Therapy, however, should be given as soon as possible to allow the damaged brain to recover. CT scan in first 24 h after an infarct might appear normal; if so, it will need to be repeated if no MRI can be performed. Haemorrhage can usually be seen. An MRI scan shows an infarct early in the diagnosis.

Further management – rehabilitation

• Physiotherapy to maximise functional recovery and prevent contractures.

• Occupational therapy for functional assessment, aids and adaptations.

• Speech and Language Therapist (SALT) for assessment and management of speech and swallowing problems.

Post-stroke care and rehabilitation in stroke units has been shown to reduce mortality and early disability.

Secondary prevention after stroke

• Hypertension: persisting at 28 days after stroke should be treated according to British Hypertension Society Guidelines (p. 317).

• Anti-platelet agents: aspirin (75–150 mg daily) and clopidogrel 75 mg daily should be started. Dipyradamole MR (200 mg) is used if clopidogrel 75 mg daily is contraindicated or not tolerated.

• Anti-coagulation in patients with ischaemic stroke who make a reasonable recovery and have AF, mitral valve disease, prosthetic heart valve or within 3 months of myocardial infarction.

• Carotid endarterectomy if carotid stenosis of 70–90% is present in patients who are not severely disabled by their stroke. Early investigation and surgery should be performed within one week (p. 478).

Heart disease in the elderly

What investigations would you do?

Investigations revealed AF with no R wave progression on his ECG, suggesting a possible acute myocardial infarct.

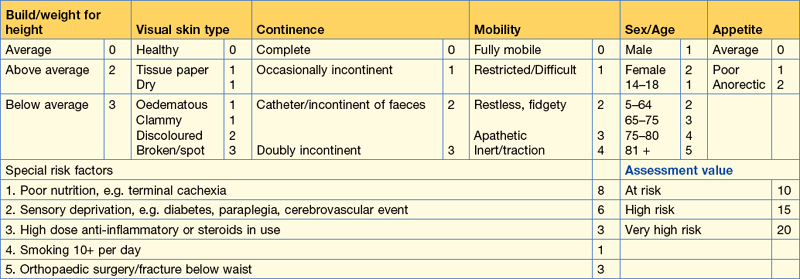

His CXR showed pulmonary oedema (Fig 7.2a). The FBC showed an Hb of 98 g/L with an MCV of 70 fL, suggesting an iron deficiency anaemia, possibly related to his aspirin intake.

Learning points

• Cardiac failure in the elderly may present with non-specific symptoms such as tiredness and falls.

• Aspirin, even at low dose, can be associated with occult GI blood loss.

• Always check compliance in older people, especially if patient thinks that medication is not effective.

• Benefits have been shown for anti-coagulation of elderly patients in AF up to age 85, but contraindications (e.g. falls or gastrointestinal haemorrhage) are more common in this population. In this case the microcytic anaemia (see p. 79) would need to be investigated before starting warfarin.

• Risks of anti-coagulation in the over 85s are high and no study has shown a benefit in this age group.

• ACE inhibitors should be used in the elderly, starting with a low dose, and renal function closely monitored due to increased risk of renal impairment (p. 236).

Acute MI

Acute MI may present silently (with no pain) more commonly in the elderly.

Treatment

He was given diuretic therapy with furosemide 40 mg orally daily. This helped his breathlessness and his ankles became less swollen. His CXR improved (Fig. 7.2b). As his presentation was over a few days he was not given fibrinolytic therapy. He was started on an ACE inhibitor with enalapril 2.5 mg.

Transient ischaemic attack

What points do you need to ascertain in the history?

What are the major aspects of the examination?

Should you admit this patient?

How would you manage a case of TIA?

Further management – carotid endarterectomy (see also p. 478)

The ABCD2 score can help to stratify stroke risk in the first 2 days (see p. 478).

Hypothermia

Clinical features

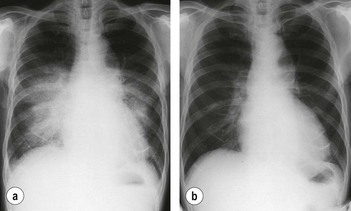

The electrocardiograph can show changes such as sinus bradycardia, slow AF, prolonged PR interval, ‘J’ waves (commonly seen in leads V3-V4) (Fig. 7.3).

This patient was found to be grossly hypothyroid with a TSH of 14.3 mU/L and a T4 of 4 pmol/L.

How would you manage this patient?

This patient was managed as follows:

• Nursed with space blanket in a warm room (allow temperature to rise by 0.5°C/h).

• Oxygen: remember that patients with COPD might require 24% oxygen.

• IV fluids (through blood warmer).

• Her severe hypothyroidism was treated with triiodothyronine 5–10 µg slowly IV 12-hourly.

A severely hypothermic patient will require admission to ITU and require positive pressure ventilation, CVP line, and ECG monitoring may be necessary.

Pressure ulcers

Risk factors for developing pressure ulcers

Why do pressure ulcers occur?

Pressure ulcers can be graded into superficial (grades 1 and 2) and deep (grades 3 and 4).

Clinical assessment

Document pressure ulcers fully:

• The site, size and grade of pressure ulcer

• The condition of the surrounding skin

• The presence/absence of infection

• Photography is a good method of recording pressure ulcers and monitoring change.

General examination of the patient with special regard to:

How would you investigate?

Investigations

• FBC: presence of anaemia will delay wound healing

• Albumin: marker of nutrition, low albumin will delay wound healing

• Blood sugar: hyperglycaemia delays healing

• Wound swabs for culture and sensitivity

• Blood cultures if concern about septicaemia

• If the wound is deep, overlies a bony prominence and has been present for some time, X-ray of the underlying bone should be performed to rule out osteomyelitis

How would you manage pressure ulcers?

Prevention is definitely better than cure and all at-risk patients require immediate assessment.

• Relief of pressure with appropriate support mattress and/or cushion for chair:

• Appropriate dressings for wounds. Note: dry dressings should not be used on moist wounds. Examples of dressings include:

• Treatment of infection (cellulitis or associated septicaemia) when present, with appropriate systemic antibiotics.

• General management of the patient:

• Severe pressure ulcers often require surgical debridement and skin grafting by plastic surgeons, when non-infected.

Most hospitals have tissue viability specialist nurses to advise on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. For quantification of risk, these nurses can use the Waterlow score or Norton Scale (see p. 165).

Urinary tract infection and incontinence

Particular points to note in the history

• Urinary tract infection in the elderly can present with non-specific symptoms such as confusion, drowsiness or falls.

• Recurrent UTIs should be investigated (> 3 in a woman, > 1 in a man) with renal tract ultrasound, including assessment of post-micturition bladder volume.

• New urge incontinence may be precipitated by infection leading to an unstable bladder.

• Infection can be precipitated by obstruction: most commonly caused by constipation or prostatic hypertrophy.

• Drug history for precipitating causes: drugs causing constipation, diuretics, sedatives.

Examination of this patient included:

• Full physical examination for coexisting causes of confusion, e.g. chest infection.

• Rectal examination – to assess for constipation/overflow (prostatic enlargement in men).

• Neurological examination to exclude neurological causes of urinary retention and constipation.

Investigations

• Stix testing positive for both leucocytes and nitrites is highly specific and sensitive for infection: blood and protein Stix are much less useful. Note: bacteriuria without symptoms (urgency, frequency, dysuria or systemic symptoms) is common in hospitalised/institutionalised older people and should not be treated, even if bacterial count is > 105

• In–out catheterisation can be useful for obtaining specimens or assessing residual volumes. However, catheterisation should not be used as a treatment for incontinence

• AXR for evidence of constipation

• Consider further assessment of incontinence if it doesn’t settle on treatment of infection

How would you treat this patient?

• Treat infection with oral antibiotics.

• Treat constipation: enemas and laxatives (see p. 36). Stop co-dydramol. Repeat residual volumes after constipation is treated as this patient’s constipation was likely to be due to the codeine in co-dydramol. The latter was replaced by paracetamol.

Arteritis

Medical assessment

Investigations revealed a significantly elevated ESR (> 100 mm in 1 h).

A clinical diagnosis of temporal arteritis (see p. 212) was made. His response to steroids was very good, although he remained tired and slightly more frail than previously

General points for discharge planning

The assessment by MDT includes:

• Assessment by a physiotherapist to assess his/her mobility, transfers and ability to climb stairs.

• Assessment by an occupational therapist to assess independence and safety in activities of daily living, kitchen assessment and/or a home visit.

• Social work assessment that will take into account the assessments of other professionals to quantify his/her needs for care on discharge.

• Assessment by a speech and language therapist, dietitian or a psychologist in some cases.

• Referral to a district nurse, e.g. for treatment of leg ulcers, monitoring of diabetic control, monitoring of medication.

Following discharge it might be possible to continue further rehabilitation or monitoring of medical or nursing care in a day-hospital setting.

Acute hot joint

What are the possible causes?

On examination you should look for:

• Temperature, pulse: systemic signs of infection/inflammation

• Joint colour, temperature and tenderness

• Other joint disease, including evidence of RA or osteoarthritis (OA).

Joint fluid should be sent for culture, cell count and examination under polarised light. Urate crystals are distinguished by being negatively birefringent. Calcium pyrophosphate consists of weakly positively birefringent rhomboidal crystals.

How would you manage this patient?

This patient’s serum uric acid is in the high range 700 µmol/L which is compatible with gout.

Treatment

There are three acute options:

• An NSAID: e.g. ibuprofen 400 mg × 3 daily or diclofenac with misoprostol one tablet × 3 daily (Misoprostol is a cytoprotective agent to the gastric mucosa).

• Colchicine (rarely used only because it causes diarrhoea): 1 mg initially, 0.5 mg every 2 h until attack subsides or 0.5 mg × 2 daily for 5 days if symptoms are not severe.

• Intra-articular corticosteroids: injection with methylprednisolone 40 mg with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine.

Allopurinol should not be used acutely. Prophylactically, it is started at least 4 weeks after the acute attack has settled to prevent further attacks of gout.

Parkinson’s disease

Features of PD

How would you manage this patient?

• This patient was started on L-dopa as first-line treatment (e.g. Co-beneldopa 62.5 mg × 2 daily) as it is useful in the elderly. Dose requires titration depending on improvement and side effects of medication, e.g. postural hypotension, nausea, hallucinations.

• Synthetic dopamine agonists (Ropinirole, Pramipexole) are less effective but might be useful in early disease. Hallucinations and somnolence are common side effects but they are tolerated by approximately 46% of very elderly patients. They may need to be used with domperidone to avoid gastrointestinal side effects. Other dopamine agonists have ergot side effects and are poorly tolerated by the elderly.

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI-B): selegiline – avoid in patients with postural hypotension or hallucinations.

• Catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitor (COMT) inhibitors (e.g. tolcapone, entacapone) are used as adjuncts to L-dopa.

• Apomorphine SC infusion is used in specialist centres.

• The frequency of his falls improved with PD therapy but nevertheless, exercise and balance training was started. He was referred to an MDT to assess need for walking aids and changes in the home environment.

Drug treatment in older people/drug treatment as a cause of illness and admission to hospital

The most frequently used classes are cardiovascular drugs, analgesics, gastrointestinal preparations and sedatives (Table 7.9).

Table 7.9 Drugs that are more likely to produce adverse effects in the elderly

| Drug | Adverse effects |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | Sedation, drowsiness, confusion, ataxia |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Gastric erosions, fluid retention, renal impairment and drug interaction, e.g. diuretics |

| Opiates | Sedation, confusion, constipation |

| Antimuscarinic | Urinary retention, glaucoma |

| Antiarrhythmics | Confusion, urinary retention, thyroid problems |

| Antipsychotics | Confusion, sedation, tardive dyskinesia, malignant hyperthermia |

| Diuretics | Dehydration, hyponatraemia, hypo- or hyperkalaemia, postural hypotension, renal impairment, gout |

| Antibiotics | Renal failure, diarrhoea, auditory complications |

Drugs as a cause of illness and delayed discharge

Case history (1)

A few days later she developed watery diarrhoea, which was bad enough to require IV fluids. Her stool analysis was positive for Clostridium difficile toxin (see p. 9). She was prescribed a 10-day course of metronidazole 400 mg × 3 a day. Apart from transient nausea, she made a good recovery from her diarrhoea and was able to go home after 6 days.

Case history (2)

A 71-year-old woman was admitted with malaise, fatigue, weight loss and generally feeling unwell.

On examination she looked anxious, underweight and tremulous with a tachycardia.

In the past she had suffered from atrial fibrillation and was taking amiodarone 200 mg once daily.

The amiodarone was stopped and her cardiologist contacted about alternative therapy for her AF (p. 275). She was started on anti-thyroid therapy (carbimazole 10 mg × 3 daily) and steroids (prednisolone 40 mg once daily). Her response was slow and she remained an inpatient for 2 weeks before her condition was brought under control. She was seen in the Endocrine Clinic for dose adjustment of her carbimazole.

Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) decision-making

What principles might guide you to decide to withhold CPR?

• Likely effectiveness of CPR: only 6–15% of patients who undergo CPR leave hospital alive. A number of factors predict a poor outcome from CPR attempts. These include:

• Patient’s wishes: these can be ascertained in advance or from advance directives and living wills. Mentally competent patients who express their wishes on treatment, including CPR, must have those wishes respected. The guidance also recommends that a patient can refuse to accept a DNAR (do not attempt resuscitation) order made by a clinician and that, under the Human Rights Act (in HR), doctors must respect this decision and record the change. However, if a patient is not mentally competent to decide whether to accept CPR, the doctor must consult family/carers and/or the family doctor to ascertain what the patient’s wishes would have been. He/she then uses this information to ‘act in the patient’s best interest’. Note: there is no provision in law in England and Wales for relatives to make medical decisions, including CPR, on behalf of an adult.

• Quality of life: this is the most difficult aspect to address. It includes quality of life as it is now and also after a CPR attempt, which might be worse. Difficulties arise because it involves professionals making value judgements about other people’s lives.