32 Care of the ear, nose, throat, neck, and maxillofacial surgical patient

Ankyloglossia (Tongue Tied): A short lingual frenulum that may cause difficulty with suckling in the infant and subsequent speech impairment. It is treated surgically with clipping of the frenulum.

Cochlear Implant: A prosthesis with an internal electrode is surgically implanted into the cochlea so that an external microphone later can be applied for stimulation of the eighth cranial nerve and provision of sound for a deaf person.

Electrocautery Unit: A snare heated with electricity for the purpose of cauterization of small vessels to bleeding or for cutting tissue, without blood loss.

Endoscopy: Nasal surgery performed with direct vision with endoscopic equipment.

Ethmoidectomy: Removal of ethmoid bone.

Fenestration: Reconstruction of the outer and middle parts of the ear by means of a new drum or skin flap; creation of a new window into the internal ear mechanism with a newly established drum or skin flap.

Glossectomy: Removal of the tongue.

Intranasal Antrostomy (Antral Window): Creation of an opening in the lateral wall of the nose under the middle turbinate and the removal of the anterior end of the inferior turbinate.

Labyrinthectomy: Opening of the labyrinth to destroy the inner ear in an attempt to relieve medically uncontrollable symptoms of unilateral Meniere disease.

Laryngectomy: Removal of the larynx; total laryngectomy is the complete removal of the cartilaginous larynx, the hyoid bone, and the strap muscles connected to the larynx and the possible removal of the preepiglottic space along with the lesion.

Laryngofissure: Opening of the larynx for exploratory, excisional, or reconstructive procedures.

Laryngoscopy: Direct examination of the interior of the larynx with a laryngoscope.

Mastoidectomy: Removal of mastoid air cells and of the tympanic membrane. Radical mastoidectomy also involves removal of the malleus, incus, chorda tympani, and mucoperiosteal lining.

Myringotomy: Incision of the tympanic membrane with direct vision and insertion of tubes for facilitation of drainage.

Ossiculoplasty: Reconstruction of the ossicular chain.

Palatouvuloplasty: The reconstruction of the posterior section of the palate and the uvula.

Radical Antrostomy (Caldwell-Luc Operation): Use of an incision into the canine fossa of the upper jaw and exposure of the antrum for removal of bony diseased portions of the antral wall and contents of the sinus; establishment of drainage by means of a counteropening into the nose through the inferior meatus to create a large opening in the nasoantral wall of the inferior meatus, which ensures adequate gravity drainage and aeration and permits removal of all diseased tissue in the sinus with direct vision.

Semi-Fowler Position: The patient is in an inclined position, with the upper half of the body raised with elevation of the head of the bed by approximately 30 degrees.

Sensorineural Hearing Loss: The sound is conducted normally through the external and middle ear, but a defect in the inner ear or auditory nerve results in a loss or deficit in hearing.

Serosanguineous: A discharge from the body that is composed of serum and blood.

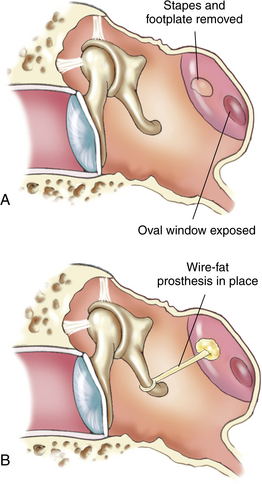

Stapedectomy: Removal of the stapes, followed by the placement of a prosthesis.

Stents: A rod for supporting tubular structures.

Submucosal Resection: Removal of either cartilaginous or osseous portions of the septum that lie between the flaps of the mucous membrane and the perichondrium for establishing an adequate partition between the left and right nasal cavities, thereby providing a clear airway for both the internal and the external cavities and the parts of the nose.

Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy (T&A): Surgical removal of the tonsils and adenoids.

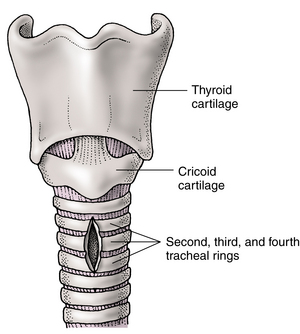

Tracheostomy: Opening of the trachea and insertion of a cannula through a midline incision in the neck below the cricoid cartilage.

Tympanoplasty (Myringoplasty): Reconstruction of the tympanic membrane.

The patient with ear, nose, and throat (ENT) dysfunction presents many challenges to the perianesthesia nurse. These patients often have a difficult airway for management (see Chapter 30), which in itself can be challenging. These patients also often have abnormal or dysfunctional anatomy that presents major concerns and requires enhanced awareness of the “normal” anatomy of the structures associated with ENT surgical procedures. In addition, the patient emerging from maxillofacial surgery, which usually consists of dental or plastic surgery, needs close monitoring of airway patency and clearance along with management of the pain associated with those surgical procedures in a way that does not depress respiratory status. The perianesthesia nurse who manages these types of surgical procedures needs a strong knowledge of airway anatomy and physiology and excellent skills in the management of a difficult airway. Finally, the perianesthesia nurse must also manage the behavioral component of patients who undergo ENT or maxillofacial surgery. These patients have all kinds of emotions: from fright because of wiring of the jaw to fear because of the tight bandaging and pain. Because patients who undergo ENT and maxillofacial surgery present a great challenge to the perianesthesia nurse, a complete review of this category of surgical patients is presented. The reader is encouraged to read Chapters 12 and 30 as follow-up; they present more information on the respiratory system and airway management.

Surgery on the ear

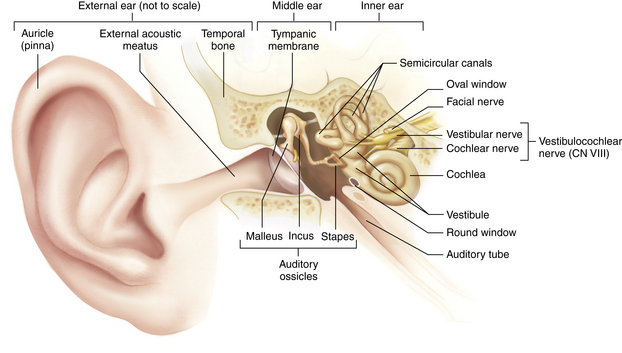

Otologic surgery has been revolutionized by antibiotics, the operating microscope, new and more delicate instruments, and an increased understanding of the anatomic structures involved (Fig. 32-1). New methods have been devised for the surgical treatment of hearing loss with correction of conduction apparatus abnormalities, and selected patients can now be surgically relieved of the disabling symptoms of sensorineural hearing loss.

FIG. 32-1 Frontal section through outer, middle, and internal ear. CN, Cranial nerve.

(From Thibodeau GA, Patton KT: Anatomy and physiology, ed 7, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Most otologic procedures are performed in the day surgery arena. The immediate postanesthesia care for patients who have undergone surgery on the ear is generally the same, regardless of the procedure. Immediate postoperative complications are rare. Occasionally excessive bleeding may occur, especially if a large blood vessel has been entered during the operation. If bleeding has occurred, the incident should be reported to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) nurse who provides care for the patient on admission. Immediate postanesthesia assessment should follow the same format as for any patient who undergoes general anesthesia.1 In addition, postanesthesia assessment should include testing for function of the facial nerve. The patient should be instructed to frown, smile, wrinkle the forehead, close the eyes, bare the teeth, and pucker the lips.2 An inability to perform these actions indicates injury to the facial nerve and should be appropriately indicated in the patient’s medical record and reported to the surgeon.

If surgery has been performed near the brain (e.g., the inner ear), check for clear fluid in the ear or on the dressings that may indicate cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Aseptic technique for all dressings and protection from infection are especially important elements in the care of the patient who has undergone surgery on the ears, because infection can be transmitted easily to the meninges and the brain. The outer ear is highly vascular and susceptible to circulatory damage and excoriation. The outer ear may even become necrotic if circulation is impaired by poor positioning or excessive pressure of a dressing. Assessment of the dressing should therefore include proper positioning.2,3

Nausea, vertigo, and nystagmus commonly occur in patients after ear surgery. The patient may minimize discomfort by remaining in the position ordered, moving slowly, and avoiding quick jerky movements.2,3 The patient should be advised to take slow, deep breaths through the mouth to minimize nausea. Antiemetic drugs and sedatives, such as a 5-HT3 antagonist (e.g., ondansetron [Zofran]) may be ordered for prevention or treatment of nausea and vertigo. The nurse should avoid jarring the bed. When approaching the patient, the nurse should place a hand on top of the patient’s head as a reminder not to turn suddenly when the nurse speaks. Sudden turns should be avoided, and movement should be slow in patient transport. Particular attention must be paid to maintaining the integrity of the airway should nausea and vomiting occur.

Special considerations

Myringotomy

Myringotomy is the most common procedure performed on infants and small children; it is performed for eustachian tube dysfunction. Often these children will exhibit frequent ear infections or symptoms of pain, poor coordination, hearing loss, or speech delays.4 After a hole in the tympanic membrane is created with a myringotomy blade, the surgeon will place a tube to maintain patency. There are several types of tubes and are placed according to the surgeon’s preference.5

Special pediatric considerations must be given in the immediate postanesthesia phase to airway management, safety, parental involvement, and outpatient teaching.3 This procedure is commonly bilateral in children; however in adults it is commonly unilateral.4 A small piece of sterile cotton can be placed loosely in the external ear to absorb the drainage that commonly occurs. The cotton should be changed when saturated to avoid contamination.

Mastoidectomy

A firm bulky dressing is placed over the ear and held in place with a circular head bandage after mastoidectomy.5 This dressing may be reinforced, if necessary, but should be changed only by the physician. Minimal serosanguineous drainage may be expected, but bright bloody drainage should be reported to the surgeon.

The patient should be placed in a position of comfort, usually on the nonoperative side. Grafts are often taken from the arm or leg for radical mastoidectomy, and the donor sites should be assessed for drainage and treated according to facility or department policy and surgeon preference. Dizziness and vertigo are common after mastoidectomy and can be treated with the previously mentioned measures.2,3

Stapedectomy

Patients who have undergone stapedectomy are usually admitted to the PACU with ear packing in place; this packing should not be disturbed5 (Fig. 32-2). Occasionally patients have vertigo after surgery. Patients should be advised to avoid blowing the nose, coughing, and sneezing.

Cochlear implant

Patients who have undergone a cochlear implant need the same postanesthesia care as any other patient for ear surgery. Verification of the integrity of the facial nerve is important. These patients do not have hearing immediately after surgery and need emotional support and a means of communication such as pen and paper, white board and markers, or a sign language interpreter.3

Surgery on the nose and sinuses

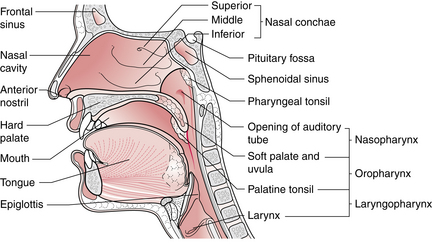

Nasal and sinus surgery can be accomplished with local or general anesthesia. The disposition of the patient is determined by the nature and type of surgery and anesthesia and by the perianesthesia course related to complications and sedation required in the PACU.6 Although no longer common with the use of endoscopic procedures, overnight observation of the patient in an inpatient setting may be necessary before discharge from the hospital. An inpatient stay may be considered for patients with comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea because they will have some difficulty with use of the CPAP machine owing to the nasal splints or packing.7 The anatomy of the nasal cavity is shown in Fig. 32-3.

FIG. 32-3 Sagittal section of the nose, mouth, pharynx, and larynx.

(From Watson R: Anatomy and physiology for nurses, ed 13, London, 2011, Baillière Tindall.)

Nasal surgery

Conscious patients admitted to the PACU after nasal surgery, such as septoplasty or functional endoscopic sinus surgery, should be placed in a semi-Fowler position to promote drainage, reduce local edema, minimize discomfort, and facilitate respiration. Some postoperative serosanguineous drainage is expected; however, the nurse should observe closely for gross bleeding.2 Loss of vision is a complication that may indicate orbital hematoma required immediate attention by the surgeon. The patient is usually admitted with one or both nostrils packed and a mustache dressing in place to catch any drainage from the packing.5 The position of the nasal packs and the amount of drainage should be checked frequently. The mustache dressing may be changed as necessary; two or three changes within a 4-hour period are not unusual. Another method commonly used to facilitate postoperative drainage is the insertion of nasal stents. This approach affords more comfort and permits nasal breathing.

The back of the patient’s throat should be checked frequently for blood. Frequent belching (from the accumulation of blood in the stomach), frequent swallowing, and the classic signs of hemorrhage, such as tachycardia, are additional signs of unusual bleeding.3 The patient should be instructed not to blow the nose or swallow secretions, but to spit them into a basin. An ample supply of disposable tissues along with an emesis basin should be placed within easy reach of the patient.

Airway obstruction or laryngeal spasm can occur if a postnasal pack accidentally slips out of place.1 A flashlight, scissors, and a hemostat for emergency removal of nasal packing and emergency airway equipment must be kept readily available at the patient’s bedside.

Sinus surgery

After surgery on the sinuses, the patient is usually admitted to the PACU with packing or splints in place. Reports of feelings of numbness in the upper lip and teeth are not unusual. After general anesthesia, the patient should be positioned well on one side to prevent aspiration of drainage. The conscious patient should be placed in a semi-Fowler position, with the head elevated 45 degrees to promote drainage and minimize edema. The same general care, including oral hygiene and instructions to the patient not to blow the nose, should be followed as for the patient with nasal surgery.1–3

Surgery on the tongue

The tongue occupies a large portion of the floor of the mouth. Surgery on the tongue generally involves excision of benign or malignant lesions, correction of congenital anomalies, or repair of traumatic lacerations. Lesions may be excised without associated neck dissection; however, when the lesion is malignant, surgical treatment usually involves a combined operation that may include radical neck dissection and resection of both the mandible and the tongue.2,5

Maintenance of the airway is the most crucial nursing concern. Suctioning equipment with soft-tipped catheters must be immediately available at the bedside.1,3 The patient should be instructed to allow saliva to run out of the mouth. A wick of gauze is placed in the patient’s mouth to assist in the elimination of secretions. Swelling of the tongue can occur and obstruct the airway; therefore an intubation tray should be readily available.

Because of the vascular nature of the tongue and oral cavity, postoperative bleeding may be a problem. If excessive bleeding occurs, local pressure should be applied until the surgeon can be notified and repair can be performed in the operating room.

Throat surgery

Surgery on the throat and neck is generally accomplished with general anesthesia.6 Aside from routine care and assessment, specific postanesthesia care for the patient who has undergone surgery on the throat involves: (1) close observation for bleeding from the surgical site; (2) maintenance of a patent airway; (3) prevention of aspiration of secretions; and (4) awareness of possible cerebral neurologic complications that may develop.

The most common procedures are tonsillectomy, either alone or in combination with adenoidectomy, and tracheostomy.8 Other procedures that are performed on the throat include laryngoscopy with or without biopsies and laryngectomy.

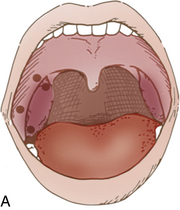

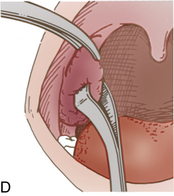

Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy

Most patients who undergo tonsillectomy (Fig. 32-4) and adenoidectomy (T&A) are children and young adults. However, the number of the young children for T&A continues to be reduced each year as a result of excellent antibiotic treatment. Patients who have undergone T&A and are admitted to the PACU fully conscious can be positioned on their backs with the head elevated 45 degrees. Patients who return after general anesthesia and who are unconscious or semiconscious must be placed in the tonsillar position—well over on the side with the face partially down. The Trendelenburg position can be used to facilitate drainage. The patient’s airway and chest expansion must be in full view of the nurse to ensure maximal respiratory integrity at all times. In this position, secretions are easily drained from the mouth.2 An oral airway should be left in place until the swallowing reflex has returned and the patient can handle secretions. The patient should be advised to spit out secretions as much as possible and to try not to cough, clear the throat, blow the nose, or talk excessively. An ice collar can be applied to minimize pain and postoperative bleeding. The administration of cool humidified air to the patient after T&A provides comfort, helps to minimize swelling, and supplies oxygen. As soon as oral intake is permitted, ice chips should be offered to moisten the throat and reduce swelling.

The most common complication of T&A is postoperative bleeding, for both children and adults. Frequent swallowing, clearing of the throat, and vomiting of dark blood are indications of possible bleeding. The nurse should frequently check the back of the throat with a flashlight for trickling blood. If any of the cardinal symptoms of hemorrhage occur, such as decreased blood pressure, tachycardia, pallor, and restlessness, the surgeon should be notified.3 Because the surgeon may want to treat a bleeding episode in the PACU, a tonsil tray should be available (Box 32-1). An electrocautery unit and appropriate illumination with a headlight should also be available, along with suction equipment. Postoperative bleeding after T&A can often be controlled with the application of vasoconstrictors via nasal packing with pressure. If significant bleeding occurs, however, the patient may have to return to the operating room for suturing or cauterizing of blood vessels.

BOX 32-1 Contents of Tonsil Tray

With the advent of laser dissection of tonsils and adenoids, swelling of the tissue in the hypopharyngeal area is increased. Close observation and measures to alleviate swelling are crucial. The advantage of laser dissection is that the potential for bleeding is significantly decreased.9

Once the patient is conscious and the reflexes have returned, ice chips and fluids may be offered. Oral liquids should be started with caution as the tonsillar beds were infiltrated with a local anesthetic. Have suction readily available in the case of choking or difficulty swallowing. Some practitioners prefer patients not to use straws so not to precipitate bleeding. Oral hygiene, including alkaline mouthwash, may provide comfort. Ointment should be applied to the lips to prevent drying and cracking.

Patients who have undergone T&A are especially prone to laryngospasms and must be observed closely for patency of the airway.1 Airway obstruction may be created by swelling of the palate or nasopharynx, swelling in the retropharyngeal space, or swelling of the tongue and nose. If laryngospasm does occur, positive pressure via a bag-mask device and 100% fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) is administered. If this method is not effective in breaking the spasm, reintubation and administration of succinylcholine and opioids as prescribed may be necessary.1,6

Laryngoscopy

Laryngoscopy can be accomplished with local or general anesthesia. If the patient’s gag and cough reflexes have been obliterated, the patient should not be given anything orally until these reflexes have fully returned.2,3 The conscious patient may be placed in a semi-Fowler position on either side. If unconscious, the patient should be placed in the side-lying position to avoid aspiration. Cool mist, sips of water, and intravenous opioids may help to relieve the coughing that often occurs.

These patients are especially susceptible to the development of laryngospasm, and the most important observations in the patient after laryngoscopy are aimed at ascertaining the patency of the airway. Laryngeal stridor, dyspnea, decreased oxygen saturation, or shortness of breath should alert the nurse to respiratory impairment, and the anesthesiologist should be notified.1–3 Equipment for endotracheal intubation and emergency tracheostomy should be immediately available at the bedside should laryngeal edema or laryngospasm develop (Box 32-2).

BOX 32-2 Contents of Tracheostomy Tray

• Adson or Poole suction (without guard; 1)

• No. 3 knife handle with no. 15 blade (1)

• One-point sharp scissors (1)

• Curved tenotomy scissors (1)

• Straight mosquito forceps (2)

• Sponge stick (or forceps; 1)

• Goiter right-angle retractor (1)

• Tonsil suction with tip screwed on (1)

• Ten-mL, three-ring syringe (1)

• Needle, 25 gauge, ⅝ inch (1)

In patients who have undergone laryngoscopy (with biopsy) or removal of polyps, vocal rest is important. Coughing should be avoided if possible, and paper and pencil or a white board with markers should be made available so that the patient can communicate without talking. If intractable coughing occurs, the anesthesiologist may need to be consulted for further measures of control, including pharmacotherapeutics such as codeine and lidocaine, to suppress the cough reflex.3

Because laser surgery is common in ENT surgery and the technology has improved to a significant degree, Chapter 47 is devoted to the care of the patient after laser and laparoscopic surgery. Patients for ENT surgery, especially involving the upper airway, may undergo laser surgery because lasers enable a precise excision of tissue without significant edema and bleeding. Lasers emit one wavelength, whereas light emits multiple wavelengths. Lasers with shorter wavelengths allow for less absorption by water and therefore less tissue penetration.9 Patients who are received in the PACU after laser surgery may still have the endotracheal tube in place. Table 32-1 describes the advantages and disadvantages of the laser-resistant tracheal tubes. A debate between cuffed and uncuffed tracheal tubes continues. However, from a perianesthesia point of view, when a patient who has had laser surgery arrives in the PACU, the nurse must inquire whether the tube is cuffed or uncuffed. If the tracheal tube is cuffed, the cuff was possibly inflated with a methylene blue-tinged normal saline solution. This solution is used because it absorbs and disperses heat and does not act as a reservoir of combustion-supporting gas.5,9 Extubation should be handled as described in this chapter and in Chapter 30. Chapter 47 also provides an excellent description of the use of lasers during surgery.

Table 32-1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Available Laser-Resistant Tracheal Tubes

| TUBE TYPE | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Metal |

From Nagelhout J, Plaus K: Nurse anesthesia, ed 4, St. Louis, 2009, Saunders.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy, an incision into the trachea and the insertion of a cannula, may be done as either an emergency or an elective procedure (Fig. 32-5). Ideally, a tracheostomy is performed in the operating suite with controlled conditions. Tracheostomies are performed to improve the airway and to provide access for suctioning of secretions from the trachea and bronchi. The PACU nurse should know what condition necessitated the tracheostomy.

FIG. 32-5 Incision for tracheostomy.

(From Ignatavicius DD, Workman ML: Medical-surgical nursing: patient-centered collaborative care, ed 6, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

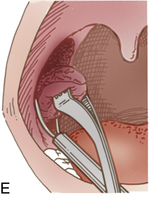

The PACU personnel should anticipate the arrival of a patient with a tracheostomy and have the necessary items at the bedside (Box 32-3). A variety of tracheostomy tubes are available, and the nurse should be familiar with those used in the particular institution. Several common types are shown in Fig. 32-6.

BOX 32-3 Bedside Equipment Needed for a Patient with Tracheostomy

Immediate postanesthesia care of the patient with a new tracheostomy includes a complete assessment of the patient’s general condition and detailed attention to respiratory status and tracheostomy wound care.3 Because of the many nursing needs and the necessity of intensive ongoing respiratory assessment, the patient with a new tracheostomy needs constant attendance.

Suctioning and tracheostomy care

Patency of the newly created airway is vital, and frequent suctioning is necessary because of increased secretions from the tracheobronchial tree caused by trauma. Suctioning of the tracheostomy must be sterile and atraumatic; a sterile disposable catheter and glove should be used for each procedure. A suction catheter in a plastic sleeve provides a means of suctioning without the use of gloves and is most convenient for use in the PACU. Catheters should be smooth and small enough to pass easily into the lumen of the tracheostomy tube without obstructing it.

If the patient’s secretions are exceptionally thick, the physician may order instillation of 3 to 5 mL of sterile normal saline solution into the tracheostomy tube to help loosen secretions and promote coughing. Although this procedure is common, whether it is actually effective is questionable; if the normal saline solution is not immediately removed with suctioning, it may produce the effects of any inhaled fluid and act as a contaminant. More effective measures to ensure liquefaction of secretions include providing inspired air that is well humidified and ensuring that the patient is well hydrated.2,3

Wound drainage from the tracheostomy is generally minimal; however, soiling of the tracheostomy dressing occurs from secretions and sweating.2 The dressings should be changed as often as necessary, and the skin should be kept clean and dry to prevent maceration and infection. The skin around the stoma should be cleansed with hydrogen peroxide and normal saline solution and dried with sterile gauze pads, and an antibiotic ointment such as bacitracin should be applied. The tracheostomy dressing should be plain gauze with the edges bound and should have no cotton filling or loose strings. Special tracheostomy “pants” that fit over the tracheostomy tube and have all edges sewn make the best dressing. Sterile gauze may be cut halfway to the center and fitted over the tube (Fig. 32-7); however, this approach has the disadvantage of cut edges that may fray and allow bits of gauze to enter the wound or the trachea.

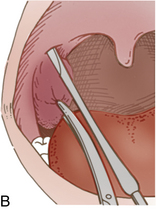

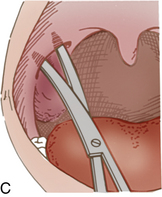

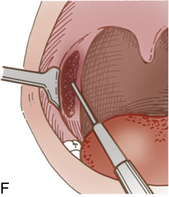

Complications

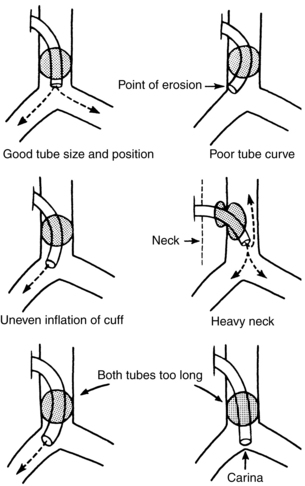

When complications of a tracheostomy occur, PACU nurses should be especially astute in observing for signs of danger. The most common complication is respiratory obstruction caused by external pressure, foreign bodies, tracheal edema, or excessive secretions. If suctioning does not relieve airway obstruction, the tracheostomy tube may be removed immediately, the tracheal stoma held open with a tracheal dilator and hook or forceps (Fig. 32-8), and the surgeon or anesthesia provider should be summoned.

FIG. 32-8 A, Tracheal dilator. B, Tracheal hook.

(From Wells MP: Surgical instruments: a pocket guide, ed 4, St. Louis, 2011, Saunders.)

Occasionally a tube is coughed out either because the ties are not sufficiently tight or because the tube is too short. If a tube is accidentally expelled, it must be reinserted by persons qualified to do so. In some institutions, nurses practice changing tracheostomy tubes under the supervision of physicians so that if accidental expulsion should occur in the PACU, the nurse is skilled in replacement. If the tube cannot be inserted easily, the stoma should be held open and the surgeon should be called.2 Misplacement or displacement of the tube is a common complication and must be corrected immediately (Fig. 32-9).

FIG. 32-9 Tracheostomy tube positions and factors that affect them.

(From Murphy ER: Intensive nursing care in a respiratory unit, Nurs Clin North Am 3:433, 1968.)

Some bloody secretions from the tracheal stoma may be expected in the immediate postoperative period, but frank bleeding is abnormal and the surgeon should be notified.2 Sometimes bleeding from a thyroid vein or other neck vessel next to the tube occurs and blood, which runs down into the trachea, is sprayed about with every cough. This situation is usually not serious and can often be controlled with local packing with petrolatum gauze. Occasionally, however, serious bleeding occurs and the patient must be taken back to the operating room, where the wound is reopened and the bleeding vessel ligated.

Subcutaneous emphysema can occur as a complication of tracheostomy if the wound is sutured too tightly about the tracheostomy tube, thus allowing air to enter the subcutaneous tissues, or it can result from an overly large incision or a partially obstructed tube. Although subcutaneous emphysema is annoying, it is usually not serious and generally clears after several days. If the nurse notices a crackling sensation under the skin of the neck, chest, or face of the patient, it should be reported to the surgeon because removal of a suture or two may readily correct this problem.

The complications of tracheostomy in infants and children are almost always more serious because the relative size of the airway is smaller and tolerance for any obstruction is lessened. Emotional support of the patient with a new tracheostomy is important and begins immediately on the patient regaining consciousness.3 Although the patient may have been well prepared in regard to the loss of ability to speak, awakening in that state is still a traumatic event. A pad and pencil should be readily available to allow the patient to communicate.

Laryngectomy

Partial laryngectomy (Table 32-2) is the surgical treatment of choice for patients with a limited malignant process of the vocal cords. It is commonly performed through a laryngofissure, and tracheostomy is usually performed concomitantly to ensure a good airway during the immediate postoperative period. Postanesthesia nursing care is essentially the same as that for a patient after tracheostomy.5

| STRUCTURES REMOVED | STRUCTURES REMAINING | POSTOPERATIVE CONDITIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Total Laryngectomy | ||

| Hyoid bone | Tongue | Loss of voice; breathing through tracheostomy; no problem swallowing |

| Entire larynx (epiglottis, false cords, true cords) | Pharyngeal walls | |

| Cricoid cartilage | Lower trachea | |

| Two or three rings of trachea | ||

| Supraglottic or Horizontal Laryngectomy | ||

| Hyoid bone | True vocal cords | Normal voice; occasional aspiration may occur, especially with liquids; normal airway |

| Epiglottis | Cricoid cartilage | |

| False vocal cords | Trachea | |

| Vertical (or hemi-) Laryngectomy | ||

| One true vocal cord | Epiglottis | Hoarse but serviceable voice; normal airway; no problem swallowing |

| False cord | One false cord | |

| Arytenoid | One true vocal cord | |

| One half thyroid cartilage | Cricoid | |

| Laryngofissure and Partial Laryngectomy | ||

| One vocal cord | All other structures | Hoarse but serviceable voice; occasionally almost normal voice; no airway problem; no swallowing problem |

| Endoscopic Removal of Early Carcinoma | ||

| Part of one vocal cord | All other structures | Possibility of normal voice; no other problems |

Supraglottic laryngectomy is performed for carcinoma of the epiglottis and adjacent structures above the level of the true vocal cords. A tracheostomy is mandatory for these patients; they also have a great deal of difficulty swallowing and need close observation and assistance with elimination of saliva and other secretions.2,3

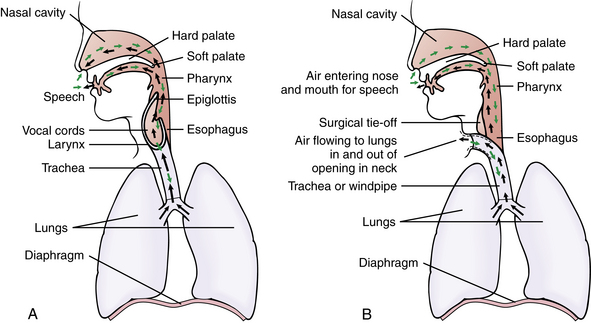

Total laryngectomy is reserved for patients with advanced carcinoma of the true cords (Fig. 32-10). Tracheostomy is always performed.5 Some means of communication should be established before surgery for postoperative use. Speech and language consultations should be performed preoperatively to determine the patients ability to care for a voice prosthetic.2

FIG. 32-10 Total laryngectomy. A, Normal airflow in and out of lungs. B, Airflow in and out of the lungs after a total laryngectomy.

(From Lewis SL, et al: Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 8, St. Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

The primary nursing concern after laryngectomy is maintenance of an adequate airway.3 Tracheostomy care, as previously discussed, should be deftly performed and the air well should be humidified. In the immediate postanesthesia period, patients need frequent suctioning, not only of the tracheostomy but also of the nose and mouth, because they cannot blow the nose and may have difficulty spitting.2 Frequent mouth care provides additional comfort, and an ointment should be applied to the lips to prevent drying and cracking.

After surgery, the patient should be positioned on the side until full consciousness is regained. While positioning, care should be taken not to cover the stoma. These patients are unable to breathe through the mouth or nose; they can breathe though only the newly created stoma.2 When conscious, the patient may be positioned in a low semi-Fowler position with the head elevated approximately 30 degrees. This position promotes drainage, minimizes edema, prevents uncomfortable pressure on suture lines, and facilitates respirations.

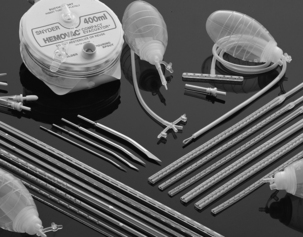

Dressings should be checked frequently for excessive drainage and reinforced or changed as necessary. Sometimes drainage catheters are placed under the wound flaps for removal of fluid from the potential dead space left after removal of the larynx and related structures.2 Drainage catheters must be connected to a constant vacuum source at 40 to 60 mm Hg, and free drainage must be maintained within the system, which can be accomplished with a Hemovac drainage device (Fig. 32-11). Excessive bloody drainage should be reported to the surgeon. The most common site of hemorrhage is the base of the tongue.

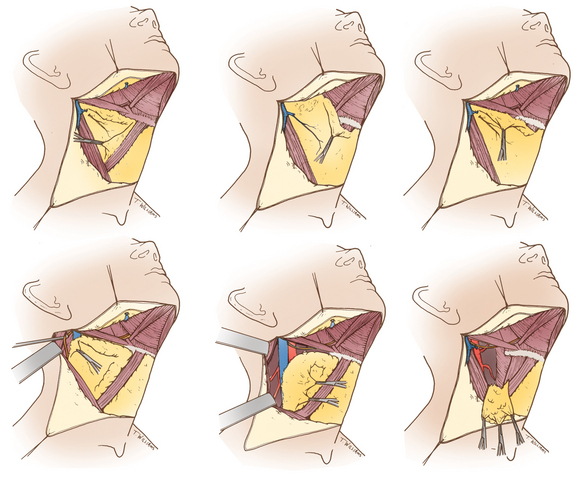

Radical neck surgery

The radical neck procedure itself is relatively simple; it involves removal of all the subcutaneous fat, lymphatic channels, and some of the superficial muscles within a prescribed area of the neck (Fig. 32-12). Generally, the procedure involves the removal of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, omohyoid muscle, internal and external jugular veins, and all lymphatic tissue on one side of the neck.2,5 The purposeful resection of the cranial nerve XI (spinal accessory) causes atrophy of the large trapezius muscle. In the modified neck dissection, the accessory nerve and the internal jugular vein are spared.

Postanesthesia nursing care of the patient after radical neck surgery is somewhat less demanding than that after laryngectomy, because these patients do not have a tracheostomy and can talk and eat normally. The patient should be placed in a low semi-Fowler position with the head elevated 30 to 45 degrees to improve venous return. Pillows must be used cautiously when patients are positioned to avoid restriction of venous return or compression of the bases of pedicle flaps. Venous congestion, when present, gives the patient’s face a purplish hue. This hue can be differentiated from cyanosis caused by inadequate ventilation with observation of the color of the extremities to confirm good circulation and close monitoring of oxygen saturation. Postoperative pain is usually minimal after radical neck dissection and can be managed with the usual analgesics.

Dressings are minimal. Skin flaps are secured over drainage tubes, which should be connected to constant suction at 40 to 60 mm Hg.5 The suction catheters constantly working under the skin flaps suck them firmly against the neck. Approximately 70 to 120 mL of serosanguineous drainage can be expected the day of operation. This amount drastically decreases the second day and becomes minimal (less than 30 mL) the third day. If the dressing soaks through with blood, the surgeon should be notified immediately.

Edema of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and of the nerves to the pharynx may cause difficulty in swallowing and in expectorating secretions; therefore frequent, gentle suctioning of oral secretions may be needed. Extreme care must be taken to avoid any trauma to the internal suture lines. A gauze wick placed in the corner of the patient’s mouth can alleviate the annoyance of constant dribbling of mucus and saliva. Mouth care is important for the comfort of this patient and can be accomplished with any of the conventional methods.

Complications

Edema of the lower part of the face on the same side as the surgery is to be expected. Lower facial paralysis may occur because of injury of the facial nerve during dissection. The most common complication after radical neck dissection is hemorrhage, which is most often the result of inadequate hemostasis in the immediate postoperative period.3 The most serious complication is rupture of the carotid artery (“carotid blowout”). This event is uncommon and occurs almost exclusively when radical neck dissection is combined with total laryngectomy. It is more likely to occur in a patient who before surgery has had a course of radiation therapy or who has a fistula that bathes the carotid artery in secretions. If the danger of a rupture of the carotid artery is present, all personnel should be aware of it and know what to do if it occurs.

Reconstruction surgery in head and neck cancer

A large variety of reconstructive procedures can be used to reestablish both contour and function after the removal of large areas of the head and neck for malignant disease. Skin grafts have largely been replaced with skin flaps or muscle-skin combined flaps that can cover extensive areas both inside and outside the neck. These flaps provide a lining of the throat or mouth and can also replace excised skin on the external surfaces.2 The commonly used flaps are the pectoralis major muscle-skin unit and the deltopectoral flap, both from the anterior chest area. In rare instances, a free flap may be used. This flap is usually a muscle-skin flap that is moved a long distance from one area of the body to another. For this procedure to be successful, this type of flap requires the microsurgical repair of its tiny artery and vein with an artery and vein in its new location. In general, these reconstructive flaps must be free of any pressure or dressings. A light coat of antibacterial ointment is usually applied along the suture lines, and the area is frequently observed for color, warmth, and bleeding. Because these flaps depend on a single small artery and vein, any kinking or external pressure may result in the death of the flap.

Maxillofacial surgery

Maxillofacial surgery may be needed to correct trauma and fractures or congenital skeletal deformities. After this type of surgery, the patient is in intermaxillary fixation (IMF) with the jaws wired shut.2 Care revolves around protection of the airway and includes wire cutters at the bedside.3 Maxillofacial surgery is lengthy, and the anesthesia time can exceed 3 hours. As a result, the patient usually arrives in the PACU in a rather sleepy condition and has a slow emergence from the anesthesia; yet in most cases, the patient is able to respond to stimuli and verbal commands.

Some additional emergency equipment is needed at the bedside of patients who are admitted with IMF, including wire cutters, a suture set, additional nasal airways, small suction catheters, and gauze pads.2 On admission of the patient, the surgeon should review placement of the IMF wires with the nurse.3 A line drawing of these wires that indicates which to cut in case of extreme emergency (e.g., cardiac or respiratory arrest) should be posted at the head of the bed.

Preoperative preparation of the patient who is undergoing IMF is particularly important and should include instructions on how to clear secretions or remove vomitus while remaining in IMF. The patient should also be taught how to use the suction catheter. These instructions have to be repeated frequently in the PACU as the patient recovers. Having the jaws wired closed is a frightening experience for any patient, no matter how well prepared that patient is. Blood, emesis, lingual and pharyngeal edema, hematoma formation, or laryngospasm may further compromise the oral airway, which is already obstructed as much as 90% by fixation of the jaws. Reassurance is provided with proximity to the patient, ensuring a means to attract attention, and explaining fully all treatments and procedures.

Vomiting and subsequent aspiration is a significant risk for this patient. A nasogastric tube is frequently used to reduce the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.3 The nurse should ensure that the tube is correctly positioned and patent. Antiemetics should be administered as necessary, and pain should be treated promptly to prevent nausea and vomiting.

Summary

Perianesthesia care of the patient after ENT and maxillofacial surgery requires basic knowledge of the pathophysiology of the face and neck. Advanced airway management skills are important in rendering nursing care to these patients. The perianesthesia nurse must also use enhanced behavioral techniques to aid the patient through the initial fear and anxiety generated by the many appliances and devices that can be placed about the oral airway. Patients who undergo maxillofacial surgery may have serious complications from the possibility of the jaw being wired or rubber bands placed to stabilize the jaw. As a result, complications such as delayed emergence from lengthy surgery and anesthesia time, possible airway obstruction from bleeding, edema, and the possibility PONV all become serious.

1. Hamlin L, et al. Perioperative nursing: an introductory text. Sydney, Australia: Mosby; 2009.

2. Stannard D, Krenzischek D. Perianesthesia nursing care: a bedside guide for safe recovery. Sudenbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2012.

3. Schick L, Windle PE. Perianesthesia nursing core curriculum: preprocedure, phase I and phase II PACU nursing. ed 2. St. Louis: Saunders; 2010.

4. Burton M, et al. Extracts from the Cochrane library: grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg.2011;14:651–657.

5. Rothrock J. Alexander’s care of the patient in surgery, ed 14. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

6. Stoelting R, Miller R. Basics of anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2011.

7. Lakdawala L. Creating a safer perioperative environment with an obstruction sleep apnea screening tool. J Perianesth Nurs. 2011;26(1):15–24.

8. Nelson M, et al. Pathologic evaluation of routine pediatric tonsillectomy specimens: analysis cost-effectiveness. Otolaryng Head and Neck Surg.2011;144(5):778–783.

9. Ball K. Lasers: the perioperative challenge. ed 3. Denver: AORN; 2004.

Aitkenhead A, et al. Textbook of anaesthesia, ed 5. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Alspach J. Core curriculum for critical care nursing, ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

Atlee J. Complications in anesthesia, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Balkany TJ. The Cochlear implant. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1986;19:217–449.

Barash P, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Bickley L, Szilagy P. Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking, ed 9. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Cote C, et al. A practice of anesthesia for infants and children, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

Drake R, et al. Gray’s anatomy for students, ed 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Fisher L. Benumof’s anesthesia and uncommon diseases, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Frost CM, Frost DE. Nursing care of patients in intermaxillary fixation. Heart Lung. 1983;12(5):524–528.

Gallager C, Issenberg B. Simulation in anesthesia. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Ganong W. Review of medical physiology, ed 22. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2005.

Miller R, et al. Miller’s anesthesia, ed 7. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Murray J, Nadel J. Textbook of respiratory medicine, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

Pop RS, et al. Perianesthesia nurses’ pain management after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: pediatric patient outcomes. J Perianethes Nurs.2007;22:91–101.

Rook JL, Rook M. Head and neck cancer. J Post Anesth Nurs. 1989;4(6):263–277.

Shorten G, et al. Postoperative pain management: an evidence-based guide to practice. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

Smalley PJ. Lasers in otolaryngology. Nurs Clin North Am. 1990;25(3):645–655.

Townsend CM, et al. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. ed 19. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.