3 Care of the critically ill surgical patient

Introduction

The term ‘critical illness’ describes the condition of a patient who has a likely, imminent or established requirement for organ support; in simple terms where death is possible without timely and appropriate intervention. Some patients are at greater risk of developing critical illness than others (Box 3.1). Also certain conditions bring a likelihood of severe physiological stress (Box 3.2). It is unfortunately commonplace for the junior surgeon to be faced with a critically ill surgical patient, in various situations-from the peritonitic teenager admitted to A&E to the elderly postoperative hip replacement on HDU. It is crucial that a systematic approach is taken to assessment and treatment.

Finally, communication has become ever more important. The maxim ‘if it’s not in the notes it didn’t happen’ is not only for the benefit of the medical defence unions but reminds us that colleagues rely heavily on written information, not only if the case is complex but especially if the author is not available to discuss the case in person. The junior surgeon will often be working shifts and be responsible for many patients, in different clinical areas and will also have to leave the hospital at the end of his/her shift. Continuity of care relies entirely on this written ‘handover’ information. A schematic is suggested in Box 3.3.

Immediate management

Unfortunately the junior surgeon is faced more often, as the attending doctor, with an unstable patient and there is a need to identify what is going on at the same time as institution of resuscitative measures (see Table 3.1). The mnemonic ABCDE is used as an aide-memoire for this systematic approach to the initial phase of critical care management, ‘immediate assessment and treatment’. By the end of this phase some common steps should have occurred:

| Observe | Examine | Treat |

|---|---|---|

| Airway | ||

Common critical care problems

Respiratory failure

Alongside baseline investigations, the full patient assessment will reveal what is the likely cause of the respiratory impairment (Table 3.2). The severity of impairment can be estimated by arterial blood gas measurement; alongside the CXR this is the most important investigation.

| Management steps | |

|---|---|

| Generic steps | Humidified O2, sit-up, IV access, monitoring in a place of safety, ABG, ECG, CXR, bloods, senior help especially if likely to need respiratory support (CPAP, BIPAP) or definitive airway |

| Airway obstruction | Relieve obstruction, adjunctive airway measures |

| Pulmonary oedema (including iatrogenic overload) | Diuretics |

| Atelectasis | Physiotherapy |

| Bronchial obstruction (acute/chronic) | Nebulised bronchodilators |

| Pneumonia | Antibiotics |

| Pulmonary embolus* | Maintain high preload, anti-coagulate |

| Myocardial infarction | Analgesia, ACS protocol |

| Pleural effusion | Consider aspiration |

| ARDS | Treat underlying cause** |

| Pneumothorax | Chest drain (needle thoracocentesis if tension) |

| Anaemia | Transfuse to 10 g/dL |

| Neurological dysfunction (e.g. sedation) | Give antidote if available, e.g. naloxone for opiate overdose, ‘bag & mask’ if poor ventilation |

Shock/circulatory failure

Full assessment

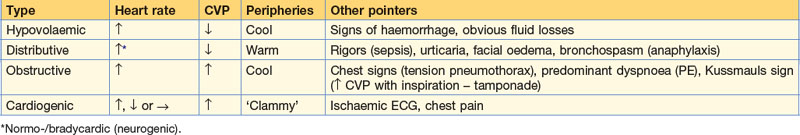

Clinical assessment (and data gathered from charts and the notes) will usually point to a typical cause (Box 3.7), but should begin by a targeted examination to establish the likely form of shock. Warm peripheries will point to a ‘distributive’ shock; that is to say where there is a failure of peripheral resistance (BP= (HR × CO) × TPR). This usually indicates systemic inflammatory response ± sepsis, but may occur in anaphylaxis or ‘neurogenic shock’ (such as spinal cord transection). Cool peripheries with signs of reduced circulating volume (low JVP, signs of dehydration, obvious fluid losses) may point to hypovolaemic shock. Cool peripheries and high JVP suggest a ‘pump failure’ – this may be intrinsic ‘cardiogenic shock’ if there has been a cardiac event (MI, arrhythmia) but can also occur secondarily to extrinsic compromise (‘obstructive shock’), tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade or pulmonary embolism (Table 3.3).

Box 3.7 Causes of cardiac compromise in surgical patients

Further definitive management depends on the exact cause and any easily reversible causes should take priority. The movement of the patient to a critical care area and the institution of invasive monitoring is invariably required, as established shock is not often rapidly reversible. Hypovolaemic states require expansion of circulating volume (to replace losses; see Chapter 4); low peripheral resistance states also require fluid replacement (as the circulating volume requirement increases) but often require inotropic support to increase arteriolar tone (see SIRS/sepsis below). Pump failure situations may require a combination of careful pre- and after-load management and in the case of cardiogenic shock, management is very difficult requiring expert cardiological input. For management of anaphylaxis see Box 3.8.

Sepsis and multi-organ failure

The body’s response to threat of injury or infection is complex, involving multiple mediators (e.g. TNF, IL-1) to co-ordinate the inflammatory response. There is clearly a balance struck between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators, and if the inflammatory response is excessive the process may ultimately harm the patient, with the development of a shock state and progressing to multi-organ failure. A continuum exists between the mild derangement of SIRS through to septic shock (Box 3.9). Certain conditions seem to predispose to an inflammatory response (Box 3.10) but there are probably other factors that determine outcome – including the severity of the insult, the delay to treatment and the underlying patient substrate (pre-existing cardiac, respiratory or renal impairment). Early recognition, immediate resuscitation and identification and treatment of any underlying cause are the key steps in management. If an infective source is suspected, prompt antibiotic administration is crucial pending more definitive treatment (e.g. drainage of abscess).

Box 3.9 Definitions in sepsis

Renal failure (Box 3.11)

• ABCs – is the patient stable? If the renal deterioration is secondary to another factor (such as hypotension due to post-operative bleeding) this must be addressed first. Assess as for all critically-ill patients (ABCDE) and resuscitate:

Although it is crucial to watch out for the complications of established renal failure (and know how to treat – see Table 3.4) these usually take a little time to develop. Fluid overload, hyperkalaemia and metabolic acidosis are easily identified by these initial steps.

Table 3.4 Complications of acute renal failure (and indications for dialysis)

| Complication | Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Hyperkalaemia | Cardiac arrhythmia |

| Fluid overload | Pulmonary oedema, respiratory failure |

| Metabolic acidosis | Coma, arrhythmias, cardiac failure |

| Uraemia | Encephalopathy, pericariditis, gastrointestinal bleeding |

Emergent treatment of hyperkalaemia (>6.5 mmol/L and/or ECG changes).

Calcium gluconate (10 mL of 10%), repeat if ECG changes unchanged at 5 min.

Insulin 10 U with 50 mL 50% dextrose over 15–30 min.

(If acidotic) sodium bicarbonate solution get expert advice.

Salbutamol 5 mg nebulised.

Take a history – what has happened to the patient recently?

For cardiac complications, see Box 3.12.

Box 3.12 Cardiac complications

A wide range of cardiac problems can occur in the critically ill surgical patient.

If presented with a cardiac arrhythmia the reader is referred to the ALS protocol (see www.resus.org.uk/pages/als.pdf

Early advice from a cardiologist is essential but early management steps are:

ABCs: ensure no easily-reversible factors

Analgesia: IV diamorphine (for pain relief if symptomatic, distress-relief if severely dyspnoeic)

Anti-platelet agent: aspirin 300 mg if cannot exclude acute infarction

Vasodilator: nitrates (sublingually initially then intravenously; improve coronary blood flow and reduce cardiac workload)