3 Care of the Child with Life-Limiting Conditions and the Child’s Family in the Pediatric Critical Care Unit

The PCCU is also a place for palliative care. How can the seemingly disparate approaches of high technology and high compassion work in concert for the benefit of children and families? The answer to this dilemma requires understanding the objectives of palliative care.32

Pearls

• Palliative care is a holistic approach to the care of the child and family when the child has a life-threatening or life-limiting condition.

• Palliative care is not the withdrawal of support, rather it is the active, total care of the child and family, with an emphasis on management of physical and emotional pain and suffering rather than on a cure for the child’s disease or condition.

• Healthcare providers need to be just as aggressive in providing palliative care as they are in providing curative therapies. Providers should begin plans to provide palliative care as soon as the life-threatening or life-limiting condition is diagnosed.

• There is never “nothing more we can do.” We can always support families as they navigate the difficult challenges of life-threatening or life-limiting conditions.

Definition

The most frightening news parents can receive is that their child has a life-threatening condition. Even more frightening and painful is the death of that child. These experiences often take place in a PCCU, where comprehensive palliative care is essential. Pediatric palliative care embraces a holistic approach to the care of a child with a life-threatening or life-limiting condition and the child’s family; it involves active, total care of the child’s body, mind, and spirit. Palliative care begins at the time of diagnosis and involves evaluating and alleviating a child’s physical, psychological, and social distress.57 To help support the best quality of life for these children, nurses need to have a clear understanding of the patients and families served, and must comprehensively address the needs of children with life-threatening conditions and their families. Nurses must provide care that responds to the anguish and suffering of patients and families, supports caregivers and healthcare providers, and cultivates educational programs.33

In the past, palliative care was not initiated until cure was no longer thought to be possible. However, many of the goals of cure-oriented and palliative care are the same, including interdisciplinary collaboration, clear and timely communication with families, and careful management of physical and emotional pain and suffering. Experts now believe that palliative care should begin whenever a potentially life-limiting condition is diagnosed.57 Unfortunately, children and families are often deprived of the benefits of palliative care because healthcare providers are reluctant to even discuss aggressive provision of comfort measures until all attempts to cure have been exhausted.

Pediatric palliative care focuses on the maintenance of quality of life for children and families, including a physical dimension that involves management of pain and distressing symptoms.26 Nurses who provide care to these children face many challenges. Physical care is important, but nurses must also address the emotional and psychological needs. A holistic family-centered model of care encourages family involvement in a mutually beneficial and supportive partnership.22 This chapter explores the needs of children with life-limiting conditions and their families in the PCCU setting, and it presents nursing interventions designed to meet the needs of the whole family.

Indications

Each year, approximately 54,000 children die in the United States, many after a lengthy illness.38 Most of these children die in hospitals, most often in neonatal and pediatric critical care units.11 The death of a child is an intensely painful experience, both emotionally and physically. In the United States, it is estimated that 1 million children are living with a serious, chronic illness that impacts their quality of life. In the PCCU, most diagnoses are potentially life-threatening or life-limiting and include trauma, cardiovascular conditions, respiratory compromise, congenital defects, and neurodegenerative disorders. Palliative care services can be beneficial at many times in the illness trajectory including diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, or end-of-life.

Historically, palliative care has been provided at the end-of-life in homes or hospice residences, but a need to integrate palliative care principles from the time of diagnosis throughout critical care interventions is becoming increasingly common. A growing number of patients with complex medical problems are alive as the result of PCCU technology, but now are dependent on that technology to continue living. These children often have residual cardiorespiratory or neurologic problems and require technologic support that is unavailable in or impractical for the home care setting. For some of these children, survival outside the hospital might not be the best option.10 Therefore, many of these children ultimately die in the PCCU. The PCCU staff might find it difficult to switch from life-saving interventions to care that focuses predominantly on addressing the comfort and psychological needs common to dying children and their families. Some children’s hospitals are developing pediatric palliative care teams or centers to ensure seamless continuity of care from critical care units to the home, and to assist the team in providing the best possible care for children with life-limiting conditions and their families.

Approaches to a family-centered model of care

Nothing can realistically prepare parents or children to face a child’s life-threatening illness or injury, but experienced nurses can provide invaluable guidance and support. Palliative care services are appropriately applied to both curable and incurable conditions, and children’s lives may be enhanced when many of the services are applied early in the course of disease treatment. Most, if not all, children with life-threatening conditions fear death or reoccurrence and pain and suffering. Caring for these children presents unique challenges for parents and for healthcare providers. Key ethical concepts include distinctions between withholding and withdrawing treatment and possible consequences such as double effect. The doctrine of double effect is used to describe giving medications with the intention of making a child comfortable, knowing one possible consequence is hastening the child’s death.51 Inherent in illness is the potential for pain and suffering that may be eased through appropriate family-centered palliative care. Strategies that enable children and their families to express their feelings, to identify realistic hopes and expectations, and to focus on using their strengths to their best advantage can facilitate optimal coping and adaptation. Family-centered care that incorporates the child’s social structure and relationships is regarded as a comprehensive ideal for end-of-life care. 51

The Child’s Needs

Admission and Diagnosis

Nurses can help families by providing careful explanations of events necessitating PCCU admission, the equipment present, and the care provided by the nursing staff. If the child is responsive, the child can be taught to communicate with the nursing staff. The child might be told, for example, that, because he has been very sick, he developed a problem in breathing, and that a soft tube (or airway or breathing tube) was put into his lungs (or into the windpipe) to help him breathe. The nurse might add that the staff is doing everything they can to help the child feel better, and the child’s parents and nurses will be close to his bed to care for him. Such communication is important even if the child appears to be unconscious. Call bells, alphabet and phrase boards, pointing, writing, and drawing can all help facilitate communication with the conscious intubated child.39,55

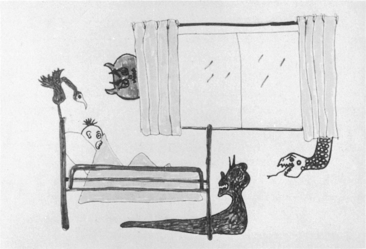

If intubation is not necessary, verbal communication is possible. The child’s questions can be more spontaneous, and the child’s answers can be more detailed and less influenced by the answer options provided by the parents or staff (i.e., not limited to yes or no). Conversations related to the PCCU environment may be stifled while the child remains in the PCCU. The child should be given many opportunities to express concerns, fears, questions, and preferences regarding care and termination of care (see Chapter 24; also see Special Considerations: Care of the Dying Adolescent in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Art and play therapy can provide a means of communication about the child’s fears, and discussion of the child’s art provides an opportunity to explore the child’s feelings (Fig. 3-1). Child life specialists can be particularly helpful in advocating for children’s wishes and assisting patients with self-expression (see also Table 2-1).

Physical Needs

Often the single most important aspect of physical care for the child with a life-limiting condition is the reduction or elimination of pain; however, studies have shown that many children are not adequately medicated to relieve their pain.16,32,56 While physicians and nurse practitioners will prescribe analgesics, nurses have a major role in recognizing and relieving pain. To identify and quantify pain and to evaluate the effectiveness of analgesics, the nurse should assess both physiologic and behavioral manifestations of pain (see Chapter 5 for further information).26,40,44 Although it can be extremely difficult to determine whether a preverbal, intubated, or obtunded child is in pain, the nurse can identify signs of distress through close observation of the child’s heart rate, respiratory rate, breathing effort, pupil size, muscle tone, and facial expression. The presence of a facial grimace or guarding, tension or flexion of muscles, pupil dilation, tachycardia, tachypnea, and diaphoresis all can indicate the presence of pain. If the nurse is unsure whether symptoms of pain are present, the nurse should ask the parents to assist in the determination of the child’s level of comfort.

Pain control uses both pharmacologic and psychologic measures (see Chapter 5 for further information about assessment and relief of pain). Although administration of analgesics can result in double effect, pain relief should be the most important physical consideration when death is inevitable.23 When healthcare team members are able to acknowledge that the child may be dying, the dying child is more likely to receive adequate analgesics

Specific treatment for dyspnea and respiratory distress in the PCCU are highly variable and need to be individualized, based on the underlying source of the dyspnea and the child’s level of consciousness and needs (see Principles of Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Supplementary oxygen, corticosteroids, diuretics, and bronchodilators may be useful approaches to care. Another relatively common symptom seen in dying children in the PCCU is delirium, which can be calm or agitated. Delirium decreases a child’s ability to receive, process, and recall information and can be mitigated with the reduction of noise and lights and by the presence of family members or familiar staff.51

Comfort measures are often as important as life-saving measures to a child with a life-limiting condition and to the child’s family. These measures can include but are not limited to soothing baths and backrubs, opportunities to be held and to play with favorite toys and pets, and diversional activities such as computers, movies, and favorite music. Such activities can reduce anxiety and pain and relieve the impersonal atmosphere of the PCCU environment.23

Emotional Needs

Establishment of effective communication is often challenging for family members, even when all are in good health. It can be especially challenging to establish effective communication for the child with a life-threatening condition, the child’s family members, and the child’s healthcare providers, because the child’s condition, treatment, and prognosis introduce additional stresses and fears (see Fig. 3-1). There are several critical points during the continuum of care when communication is especially important: at diagnosis, during exacerbations, and at the end of life. Frequently these critical points occur in a PCCU. Initiation of palliative care services might be delayed because it is difficult for families and healthcare providers to accept the fact that further curative treatment will be futile.

Parents will likely find it especially difficult to talk with the child about the severity of the child’s condition and poor or fatal prognosis. In a recent survey of parents after the death of a child with cancer, none of the parents who discussed death with their children regretted the discussions, while many of those who did not have such conversations wished they had.31 Parents were most likely to regret their failure to discuss death if they sensed that their child was aware that death was imminent.31 The nurse is often the best person to help the parents begin such discussions at appropriate times, and the nurse can help the parents to answer the child’s questions, reduce the child’s fears, and address the child’s concerns.

Spiritual Needs

Spiritual needs such as love, faith, hope, and beauty motivate human experiences, emotions, and relationships, and suffering can occur when these needs are not met.5 Palliative care attempts to address spiritual needs, bringing the child and family together around personal and private attempts to cope with questions about life and meaning that frequently result from feelings of powerlessness and helplessness.

It is important for healthcare providers to listen to families without using religious platitudes. Nurses and other members of the healthcare team can provide psychosocial and spiritual guidance consistent with family values, ideals, and choices.41 Nurses can provide a safe place where spiritual needs, uncertainty, and hope can be expressed. If hope for cure is no longer realistic, nurses can assist families in realizing other wishes, such as hoping the child does not experience pain or that the child is not alone when death comes.22 As a need for palliative care becomes apparent, parents may have intense spiritual needs. Nurses can support families through caring presence, words, and actions to foster trust.35

The Family’s Needs

Family Challenges and Strengths

Parents of chronically ill children, on the other hand, have experienced the child’s long, intense, and often complicated illness. They have likely experienced many crises during the course of the child’s illness and may have prepared repeatedly for the child’s death. Such a continuous roller-coaster of emotional stress can compromise the family’s ability to cope effectively with the child’s ultimate deterioration and death. When a child has a chronic illness and has recovered from many near-death experiences, families and healthcare professionals may be reluctant to abandon curative efforts and allow natural death. Such reluctance can result in missed opportunities for resolution and spiritual healing.27 Other family members and friends can provide valuable support, although occasionally such support people may refuse to believe that the child is really dying.

Emotional Needs

Parents may respond to a life-limiting condition or predicted death of the child with anticipatory grief. Anticipatory grief is a coping mechanism that is sometimes used when the death of a loved one is perceived as inevitable; the grieving process may begin before the death occurs, in anticipation of that loss. Parents may begin to grieve over their child’s condition at the time of diagnosis or at any time the child experiences a serious setback or relapse. Anticipatory grief has been shown to facilitate the grieving process because it provides time to prepare for loss, the opportunity to complete unfinished business and resolve conflicts, and time to say good-bye.8

Parents use a variety of strategies in response to the stress of a child’s illness. Coping involves conscious efforts to regulate emotion, behavior, and the environment through one’s response to a stressful event. Coping has been described in work with adolescents as either voluntary engagement coping or voluntary disengagement coping.14 Voluntary engagement coping includes primary control coping with direct attempts to influence stressors (e.g., problem solving, emotional expression, emotional regulation) and secondary control coping with attempts to adapt to the stressor (e.g., acceptance, cognitive restructuring, positive thinking, distraction). Parents and siblings can use either type of coping in dealing with a stressful situation, but when a situation is out of their control, evidence shows that secondary control coping seems to work best.15

Special situations affecting timing of death

Withholding or Withdrawing Treatment

Nurses often play an important role in helping parents make decisions about withholding treatments or attempted resuscitation or withdrawing therapy. The nursing staff members continuously observe the extent of the child’s suffering and its effects on the child and family, so nurses are often the best people to speak on behalf of the child and family. However, nurses must be able to objectively represent the concerns of the family during discussions with the healthcare team and must encourage parents to express preferences regarding treatment. The nurse must avoid adoption of a crusading approach during these discussions. If the nurse assumes a spokesperson role, that nurse is obligated to speak only for the child and family; the nurse’s personal opinions must be clearly distinguished from the expressed preferences of the child and family. Families benefit from and value a healthcare team that provides clear information and that hears and respects the family’s decisions.40

Emotional, religious, philosophical, legal, and ethical considerations are involved in these complex decisions. If such decisions are avoided, the terminally ill or dying child might be subjected to futile resuscitation attempts or might be forced to endure painful treatment, intubation, or surgical procedures. Often these treatments carry the risk of the most feared aspects of death: pain, loneliness, separation from parents, and loss of control. Nurses can help the child and family plan elements of a child’s last hours or days by facilitating decisions about who should be present, the location, and the timing for withdrawal of life support (see Plan for Withdrawal in the section on Principles of Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website).

If staff members and parents are unable to reach a decision about treatment termination or limitation, outside consultants may be needed to help the family and healthcare team consider the treatment options available. Historically, the federal government,43 medical13 and nursing3 disciplines, bioethics groups, and the courts4,12 have all played a part in addressing controversial issues. In the 1980s, federal legislation recommended formation of infant care review committees; in many hospitals these groups evolved into multidisciplinary ethics committees. Consultation with these committees can provide extremely helpful insight into the options available for the child. However, most decisions regarding treatment termination must still be made in consultation with the parents and the child’s primary physician, in accordance with state laws (see Chapter 24 for further information).

Futility legislation authorizes a healthcare team to withdraw suggested treatment if further life support is deemed medically inappropriate by the ethics committee and the hospital gives the family 10 days’ notice and attempts to transfer a child to an alternative provider.50 Because this legislation was passed in Texas, it is not recognized everywhere. In addition, laws can vary by state. A court order may be requested by a child-protective agency before life support is terminated for a severely ill child who is under protective custody (see Chapter 24; also see Foregoing Life-Sustaining Treatment in Children with Inflicted Trauma in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Such requests are based on individual agency policy rather than state or federal law. A court order is not required to remove ventilatory support when a child has been pronounced brain dead. These patients have died, and treatment should be discontinued (unless organ donation is pursued).

Limitation (or prevention) of attempted resuscitation requires a written document signed by a physician. Because verbal orders regarding resuscitation can be subject to confusion or misinterpretation, they should not be accepted. In the absence of a written order to the contrary, resuscitation must be initiated in the event of an in-hospital patient respiratory or cardiac arrest. However, an unsuccessful resuscitation attempt can be discontinued at any time by the physician in charge of the resuscitative efforts. If the family agrees with withdrawal of support—and only after they have made the decision to withdraw support—they should be offered the option of organ donation after cardiac death (DCD).30

Organ Donation

Although discussion of organ donation can be difficult, parents might initiate the discussion. Federal law requires that hospitals have protocols for identification of potential organ donors. In the United States and Puerto Rico, organ procurement organizations coordinate organ acquisition in designated service areas (these areas can cover all or part of a state), evaluate potential donors, discuss donation with family members, arrange for the surgical removal of donated organs, and preserve organs and arrange for their distribution according to national organ sharing policies.52

The Joint Commission also requires hospital protocols for determination of brain death and identification of potential organ donors.28 If solid organ transplantation is desired, the patient must be declared dead before these organs can be used; brain death or cardiopulmonary death criteria can be used. The coroner should be consulted if the circumstances of the child’s death necessitate a postmortem coroner’s examination. Most coroners will still allow organ donation.

Organ Donation after Brain Death

The concept of brain death is poorly understood by the general public, and most parents have misconceptions about the process and the outcomes of organ donation. Following death, many parents have stated that donation of their child’s organs helped them to find meaning in their own child’s sudden and untimely death. Surveys have shown that parents from lower socioeconomic and educational backgrounds may be less likely to consent to organ donation as a result of religious beliefs and personal attitudes.1

Organ Donation After Cardiac Death (DCD)

Uncontrolled DCD is a less common form of DCD that can occur if family members consent to immediate organ donation after the patient dies following a sudden cardiopulmonary arrest and an unsuccessful resuscitation attempt.46 After death pronouncement, the donor is moved to the operating suite or ECMO is rapidly instituted to allow organ recovery under more controlled conditions.

Controlled DCD is the most common form of DCD currently used. In this form of DCD, withdrawal of support is planned in advance. Controlled DCD occurs when a patient has catastrophic, unrecoverable brain injury or insult that does not meet criteria for pronouncement of brain death, but does result in a family and medical decision to withdraw support. The patient then becomes eligible for organ donation and, if the family consents, support is withdrawn in a sequence that will allow rapid organ recovery within minutes of cardiac arrest and pronouncement of death. During withdrawal of support, at the discretion of the child’s primary physician and according to end-of-life hospital protocols, opioids and sedatives are typically administered to minimize patient discomfort.46 In some cases, heparin is also administered to minimize formation of thrombi in the donated organs.29,46 When support is withdrawn and cardiac arrest occurs, the child’s primary medical team makes the pronouncement of death. A waiting period of 2 to 5 minutes is required either between cardiac arrest and pronouncement of death or immediately after pronouncement of death. Organ recovery cannot begin until after both the pronouncement of death and the waiting period have been completed.46

ECMO support can be used as part of the DCD protocol to allow controlled, unhurried organ recovery and improve the perfusion of donor organs before procurement.34 Premortem ECMO cannulation can occur in the PCCU to facilitate institution of ECMO immediately after the pronouncement of death and the waiting period of 2 to 5 minutes have elapsed.

DCD requires careful planning and coordination.29 All members of the healthcare team should be aware of the protocol and the precise sequence of actions, and the team should rehearse the complete sequence before it is actually implemented. When discussing the parents’ final visit with their child, the nurse should discuss the timing and sequence of all important steps, the equipment likely to be present, whether surgical drapes will be placed before death, and when the child is likely to move from the PCCU. If it is necessary to rapidly move the child to the operating suite after cardiac arrest, the parents should be aware that such movement will occur. The parents should be assured that the child’s primary healthcare team will care for the child until the child dies and the primary physician makes the pronouncement of death.46 The physicians should explain the comfort measures that they will provide for the child during withdrawal of care and before death. Parents should also be aware that they have the option of stopping the donation process if it becomes too uncomfortable or upsetting for them.30

Although members of the organ procurement agency will explain the process to the family before it begins, no member of the organ procurement team has responsibility for or involvement in the care of the child (i.e., before pronouncement of death); they will assume responsibility for the donor after pronouncement of death. Minor exceptions to this policy can include preretrieval blood sampling or administration of medications to enhance organ viability.46

Parents should be prepared for the possibility that attempts for DCD can fail because the interval between withdrawal of support and cardiac arrest is unpredictable. If the interval is too long, the organs may become ischemic and unsuitable for donation. In general, if cardiac arrest does not develop within 60 to 90 minutes29,34 after withdrawal of support, the patient is no longer considered a candidate for DCD. In such instances, care will continue to be provided by the child’s primary care team.29 Tissue donation may still be possible after the child dies.

Support of the family at or near the time of death

Talking about Death

Despite great strides in the treatment of life-threatening conditions, many of the characteristics of childhood conditions create significant challenges to parents and healthcare professionals who are communicating with a sick child about the child’s illness.54 Features that make communication challenging include the complex nature of the disease, the aversive nature of some treatments, the probability of adverse side effects, and the possibility that treatment will be unsuccessful or that the child could die from the condition. From the time of initial diagnosis and throughout the course of treatment, parents often need to talk with their children about their feelings. Parents bear the primary responsibility of filtering information and making decisions for their children. They must assimilate enormous amounts of information during an intensely emotional time, and then facilitate their child’s understanding of this information. When treatment is not successful and a child is in the terminal phase, these difficulties can be magnified.

The National Cancer Institute recommends that parents and healthcare professionals communicate openly with children about cancer, even when children are being treated palliatively.37 Because the death of a child is an intensely painful experience, few studies have examined communication strategies in families dealing with end-of-life circumstances. Thus, parents receive relatively little evidence-based guidance about the optimal ways to communicate with their child about cancer or the possibility of death.

There is general agreement that terminally ill adolescents are anxious about and aware of their severity of illness and prognosis. Studies of ill school-aged children have demonstrated that terminally ill children 6 to 12 years of age demonstrate more hospital-related anxiety, a greater awareness about hospitalization, more preoccupation with intrusive procedures, and more concerns about death and mutilation than do similar chronically ill children who are not terminally ill.42 Thus, even if the child has not been informed of the fatal prognosis, the child may be aware of and anxious about impending death.

The nurse should consider the child’s psychosocial developmental level and the ability of the child to understand when discussing concepts such as terminal illness and death. Examples of questions frequently asked by children and some suggested responses are included in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1 Potential Responses to a Dying Child’s Questions About Death

| Question or comment | Response |

| Am I dying? | “You are very sick and I am worried about you. It is possible that you might die, but we are doing everything we can to help you. Are you afraid of dying?” |

| Following the child’s answer, the nurse can explore the child’s specific fears. | |

| I’m afraid to die | “Can you tell me what scares you the most?” |

| The nurse can explore the child’s perceptions of death and reinforce the positive concepts and reduce the negative concepts. At all times, it is important to tell the child that he or she will not die alone; someone will always be with the child. | |

| I don’t want to die | “I can understand that—I don’t want to die either. What is the worst thing about dying to you?” or, “What does dying mean to you?” |

| The nurse then can explore the child’s concerns. |

While parents are key participants in the discussion of death with a dying child, they often will require assistance from healthcare professionals. Children may express their awareness of the seriousness of their illness, their concerns about dying, or their premonitions of their own death.54 This can pave the way for open discussion with the parents.7

Support During Attempted Resuscitation

When a child suffers an unexpected cardiopulmonary arrest and resuscitation is attempted, healthcare providers must be clear and compassionate when communicating with the family. Most family members prefer to be present during the attempted resuscitation of a family member. Family members who were present during an attempted resuscitation reported that it was helpful to the (surviving) child and to the family members.21 In addition, standardized psychological tests suggest that family members who are present during an unsuccessful resuscitation attempt demonstrate more constructive grieving behavior than those who are not given the option to be present.47 In a recent prospective, alternate day study, family presence did not affect the efficiency of 283 pediatric trauma resuscitations; there was no difference in time to milestones such as computed tomography scan or time to complete the resuscitation when family members were present, compared with time required in 422 resuscitations without family presence.21 Since 2000, the American Heart Associations Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care have recommended that family members be offered the option of remaining with their loved one during attempted resuscitation whenever possible.2,6 If family members remain at the bedside, the resuscitation team must be sensitive to their presence, and one staff member (e.g., nurse, chaplain, social worker) should remain with the family to answer their questions, explain what is happening, and assess and address the needs of the family members.25

Throughout the resuscitation attempt, the parents should be informed about the child’s condition and the treatment measures provided. Although it is important to provide some hope until the child’s condition is determined to be hopeless, the possibility of the child’s death should be discussed. This discussion will allow the parents to begin to prepare themselves. One of the major challenges in communicating with parents of critically ill children is the need to balance hope with reality. Statements about the child’s condition must be direct and sensitive and should involve the use of carefully chosen terms, rather than use of medical jargon or clichés. Phrases such as “He is seriously ill and may die” are more appropriate than “His condition is deteriorating,” “He just fell apart,” or “We couldn’t get him back.” Word choices are extremely important when talking with families and even carefully selected words can be misinterpreted, especially when a family is stressed (Table 3-2). The American Heart Association Pediatric Advanced Life Support Course has an excellent supplementary module to help teach healthcare providers to discuss a child’s death with parents.24

| Health Provider Statement | What the Family May Hear |

| He’s stable. (Child is supported by vasopressors, ventilator, dialysis.) | He is getting better. |

| She gained weight. (Child’s heart failure is worsening.) | She is growing well like a healthy child. |

| Do you want us to do CPR? | She may survive if we do CPR |

| Do you want us to intubate him? | He has a chance if we place a breathing tube and provide mechanical ventilatory support. |

| Ambiguous Terms | Clear Description |

| Do you want us to do everything? | Although we’ve tried many treatments for several days, unfortunately, Jason is too sick and they are not helping him to get better. |

| It’s time we talk about pulling back. | We want to provide the care that Allison needs now. Her comfort is now our highest priority. |

| I think we should stop aggressive therapy | We will change our goals of care to respect her wishes. |

| There is nothing more we can do | Let’s stop treatments that are not helping him. |

| Helpful Language | |

| I wish things were different. | |

| I hope he gets better, too, but I think it is very unlikely. | |

| How do you and your family usually deal with difficult conversations? | |

| We hope for the best, but we need to prepare for whatever may happen. | |

Informing Parents of a Child’s Death

If parents are not present when the child dies, it is ideal that news of the child’s death be conveyed by a physician and nurse whom the parents know and trust. Ideally, the parents should be told in a private room, where they can react without worrying about the presence of strangers. Buckman’s six-stage protocol for communicating difficult news describes communication, decision making, and building relations.9 This approach includes three steps to prepare for the discussion of important information (i.e., prepare for the discussion, establish what the patient and family know, and determine how information is to be handled), one step to deliver the information, and three steps to respond to the family’s reaction and planning (i.e., respond to emotions, establish goals and priorities, and establish a plan).53

Support of the Parents at the Time of Child’s Death

Sensitive and compassionate nursing care is needed to help the parents cope at the time of the child’s death.35 Parents benefit from an opportunity to express their pain and sorrow in a private place and with the supportive presence of healthcare professionals. The responses of the parents will be determined by the family’s unique method of coping with the child’s death. Nursing staff should avoid labeling or attempting to suppress grief behavior, because this is unproductive and can hinder parental progress in the grief process.

Family members might express anger, rage, and other violent emotions when a child dies. It is difficult but important for the nurse and additional support staff to remain with the family members who are expressing strong emotions or who have lost control. Too often when the parents express strong emotion, they are suppressed verbally or quickly offered medication. Sedation should not be used without careful consideration of the purpose of the medication. Too often sedatives are prescribed to meet the needs of the hospital staff or uncomfortable family members and friends, rather than to meet the needs of the parents. As a bereaved parent, Schiff wrote an honest portrayal of what the death of her son felt like. “On that bright sunny March morning we were told that Robby had died. I screamed. A nurse, tears suddenly coming to her eyes, offered me a tranquilizer and I thought, how inane. Robby was dead and I was being given a pill to make it go away. Impossible.”48

A number of bereaved parents, especially mothers, have described a lethargy or “fog” that enveloped them for days following sedation after the child’s death. Sedation may only postpone the painful reactions to a time when the parent is alone and unsupported.26 In addition, it can separate the parent from decisions about the child’s funeral or burial, and the parent might later regret lack of participation in these plans or decisions.

In time, parents may share their feelings of helplessness and begin to explore the unanswerable question “Why?” It is important to avoid suppressing these questions or negating or dismissing them. The nurse should listen to the parents concerns and indicate that feelings of guilt are normal. In addition, the nurse should reinforce the positive aspects of the parents’ role.36 The nurse can make observations about the child, such as “Everyone has mentioned that Jimmy was always smiling and happy—he certainly must have known he was loved.” When a parent is responsible in any way for the death of the child (e.g., death due to inflicted trauma), the staff members must be careful to avoid expressions of anger.

Parents need support and guidance related to the many decisions required after the child’s death (e.g., autopsy consent, informing friends and relatives, funeral and burial decisions). For many young couples, the death of their child is their first experience with the death of a loved one. Parents may need help informing siblings (see Support for Siblings).

Support for Siblings

Parents sometimes unintentionally neglect the important needs of siblings during support of the dying child. When providing information to parents about support of the siblings, the nurse must consider the siblings’ age and maturity level and the circumstances of the child’s death.53 If possible, parents should prepare siblings throughout the child’s critical illness or in the days preceding the death of the child.

Books can be helpful in facilitating discussions with siblings about death.17,18 Siblings can benefit from involvement in group therapy with other children who have experienced the death of a family member. The local chapter of Compassionate Friends or a hospital nurse or physician specialist, chaplain, or social worker may be aware of such groups.

Grief after death

The grief response observed in the hospital is only the beginning of a long phase of sorrow and pain. As the shock and numbness dissipate, parents and other family members experience a number of distressing emotions that continue for months and even years.26,45 In fact, family members are changed forever by the experience of a child’s death. Hospice and palliative care programs may speak of and try to contribute to a “good death,” but parents facing the death of their child have no perception of a “good” death and are not ever truly prepared for the child’s death.20

Parents should know that it can be therapeutic to reminisce about the child and recall happy memories. Too often in an attempt to prevent grief, these memories are suppressed, so that the parents deprive themselves of a potential source of comfort. Research has shown that continuing bonds may be a coping strategy that can increase the quality of life for bereaved families and decrease negative consequences such as marital disruptions, mental illnesses, and behavior problems.19,49

Parents often are devastated after the child dies because they were unable to protect their child from death. This feeling is based on the protective parental role in society and often produces feelings of intense helplessness and guilt. Guilt is one of the most painful and persistent emotions experienced by bereaved parents. Following a child’s death, parents evaluate their parenting experiences. This process often involves identification of discrepancies between their ideal standards of parenting and their perceived performance. This evaluation also can reinforce feelings of guilt.36

Nursing staff will often grieve after the death of the child. For further information, please refer to Chapter 24, and Burnout and Compassion Fatigue Among Caregivers in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website.

Advanced practice concepts

• Apply palliative care concepts from the time of diagnosis.

• For many years after the child’s death, parents will remember the healthcare providers who were with them when their child died and what the healthcare providers said.

• Be sensitive to spiritual and cultural perspectives.

1 Alden D.L., Cheung A.H.S. Organ donation and culture: a comparison of Asian American and European American beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):293-314.

2 American Heart Association. American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC, Part 12. Pediatric Advanced Life Support—family presence during resuscitation. Circulation. 2005;112(Suppl. IV):181.

3 American Nurses Association. American Nurses Association position statement on foregoing artificial nutrition and hydration. Ky Nurse. 1993;41(2):16.

4 Annas G.J. Asking the courts to set the standard of emergency care—the case of Baby K. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(21):1542-1545.

5 Bartel M. What is spiritual? What is spiritual suffering? J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2004;58(3):187-201.

6 Berg M.D., Schexnayder S.M., Chameides L., Terry M., et al. Part 13: pediatric basic life support. Circulation. 2010;122:S862-S875.

7 Bluebond-Langner M. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1978.

8 Bonanno G.A., Kaltman S. The varieties of grief experience. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(5):705-734.

9 Buckman R., Kason Y. How to break bad news: a guide for health care professionals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992.

10 Carnevale F.A., et al. Daily living with distress and enrichment: the moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e48-e60.

11 Carter B.S., et al. Circumstances surrounding the deaths of hospitalized children: opportunities for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):e361-e366. September 1

12 Clayton E.W. What is really at stake in Baby K: a response to Ellen Flannery [Commentary]. J Law Med Ethics. 1995;23(1):13-14.

13 Committee on Bioethics. Guidelines on forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):532-536.

14 Compas B.E., Champion J.E., Reeslund K. Coping with stress: Implications for preventive interventions with adolescents. Prev Res. 2005;12:17-20.

15 Compas B.E., et al. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):87-127.

16 Contro N., et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14-19.

17 Corr C.A. Selected literature for adolescents: Annotated descriptions. In: Corr C.A., Nabe C.M., Corr D.M., editors. Death and dying, life and living. ed 5. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth; 2006:602-609.

18 Corr C.A. Selected literature for children: annotated descriptions. In: Corr C.A., Nabe C.M., Corr D.M., editors. Death and dying, life and living. ed 5. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth; 2006:588-601.

19 Davies D.E. Parental suicide after the expected death of a child at home. Br Med J. 2006;332(7542):647-648.

20 Davies G., et al. Bereavement. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents: a practical handbook. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:196-219.

21 Dudley N.C., et al. The effect of family presence on the efficiency of pediatric trauma resuscitations. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:777-784.

22 Gilmer M.J. Pediatric palliative care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;14(2):207-214.

23 Gregoire M.C., Frager G. Ensuring pain relief for children at the end of life. Pain Res Manag. 2006;11(3):163-171.

24 Hazinski M.F., Zaritsky A.L., Nadkarni V.M., Hickey R.W., et al. Coping with the death of a child. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2003.

25 Henderson D.P., Knapp J.F. Report of the national conference on family presence during pediatric resuscitation and procedures. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:23-29.

26 Himelstein B.P., et al. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1752-1762.

27 Hutton N. Pediatric palliative care: the time has come. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):9-10.

28 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations: Health care at the crossroads: Strategies for narrowing the organ donation gap. 2008 Available from http://www.jointcommission.org/nr/rdonlyres/e4e7dd3f-3fdf-4acc-b69e-aef3a1743ab0/0/organ_donation_white_paper.pdf Accessed 05-19-10

29 Kelso CMcV, et al. Palliative care consultation in the process of organ donation after cardiac death. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:118-126.

30 Kolovos N.S., Webster P., Bratton S.L. Donation after cardiac death in pediatric critical care. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2007;8:47-49.

31 Kreicbergs U., et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1175-1186.

32 Levetown M., Liben S., Audet M. Palliative care in the pediatric intensive care unit. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents: a practical handbook. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:273-291.

33 Liben S., Papadatou D., Wolfe J. Paediatric palliative care: challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):852-864.

34 Magliocca J.F., et al. Extracorporeal support or organ donation after cardiac death effectively expands the donor pool. J Trauma. 2005;58:1095-1102.

35 Meert K.L., Thurston C.S., Briller S.H. The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(4):420-427.

36 Miles M.S., Demi A.S. Guilt in bereaved parents. In: Rando T.A., editor. Parental loss of a child. Champaigne, IL: Research Press Company; 1986:97-118.

37 National Cancer Institute. Young people with cancer: A handbook for parents. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 2002.

38 National Vital Statistics Reports. Mortality data. National Center for Health Statistics; 2008.

39 Noyes J. Enabling young ‘ventilator-dependent’ people to express their views and experiences of their care in hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(5):1206-1215.

40 Oakes L.L. Assessment and management of pain in the critically ill pediatric patient. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13(2):281-295.

41 Orloff S.F., et al. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of the child and family. In: Carter B.S., Levetown M., editors. Palliative care for infants, children, and adolescents: a practical handbook. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004:141-162.

42 Poltorak D.Y., Glazer J.P. The development of children’s understanding of death: cognitive and psychodynamic considerations. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(3):567-573.

43 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to forego life-sustaining treatment. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1983.

44 Ramelet A.S., Abu-Saad H.H., Bulsara M.K., Rees N., McDonald S. Capturing postoperative pain responses in critically ill infants aged 0 to 9 months. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2006;7(1):19-26.

45 Rando T.A. An investigation of grief and adaptation in parents whose children have died from cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1983;8(1):3-20.

46 Reich D.J., et al. ASTS recommended practice guidelines for controlled donation after cardiac death organ procurement and transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1-8.

47 Robinson S.M., et al. Psychological effect of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. Lancet. 1998;352:614-617.

48 Schiff H.S. The bereaved parent. New York: Penguin Books; 1977.

49 Silverman P., et al. The effects of negative legacies on the adjustment of parentally bereaved children and adolescents. OMEGA. J Death Dying. 2002;46(4):335-352.

50 Truog R. Tackling medical futility in Texas. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1-3.

51 Truog R., et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953-963.

52 U.S. Government Organization on Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation: Procurement Organ Procurement Organizations. 2008 Available from http://www.organdonor.gov/ Accessed 06-02-08

53 von Gunten C.F., Ferris F.D., Emanuel L.L. Ensuring competency in end-of-life care: communication and relational skills. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3051-3057.

54 Way P. Michael in the clouds: Talking to very young children about death. Bereave Care. 2008;27(1):7-9.

55 Wojnicki-Johansson G. Communication between nurse and patient during ventilator treatment: patient reports and RN evaluations. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17(1):29-39.

56 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

57 World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care for children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at