46 Care of the ambulatory surgical patient

Ambulatory Surgery Center (ASC): A facility that is separate from a hospital and may be on the same campus as or separate from other medical facilities.

Freestanding Ambulatory Surgery Center (FASC): Term used interchangeably with ASC.

Hospital Outpatient Department (HOPD): An area within a hospital that provides perioperative care for surgery patients who are discharged on the same day. These departments often function as a same-day admitting area for other surgical patients.

Joint Venture Surgery Center: An ambulatory surgery center that has more than one ownership entity, such as a corporation and physicians, a hospital and physicians, or a combination of all three.

Third-Party Payers: Payers that include insurance companies, health maintenance organizations, and the federal government; generally mandate that surgical procedures be performed in the appropriate lowest cost setting for payment eligibility. Thus, the trend has been to push procedures from hospitals to outpatient settings to physician offices. Ambulatory surgery and hospital industry organizations continually work with federal agencies to lobby for appropriate placement of procedures. Federal payment decisions often result in managed care companies following suit; therefore this is an important focus for administrators in all levels of health care settings.

Ambulatory surgery issues

Nursing care in this setting should promote wellness and self care to the degree possible. Patients should be continually encouraged to think positively and to provide self care as is appropriate and possible. Orem’s general theory of nursing, a three part theory regarding self care, self care deficit, and nursing system, provides the basis for determining and using the patient’s personal strengths relating to self care.1 The Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory describes nursing planning and intervention that is appropriate to the ambulatory surgical patient. The nurse calculates the patient’s self-care demand and shares with the patient what must be done to regain or promote health in relation to postoperative recovery. Nursing actions revolve around teaching the patient and family, gaining acceptance of the prescribed actions, and then assessing the degree to which the nurse feels the patient can and will comply.

Assessment and preparation of the patient

Careful preoperative selection and preparation of patients for outpatient surgery help to reduce the risks of perioperative complications. Nonetheless, many patients may have significant physical, emotional or social challenges, yet they return home soon after surgery or other procedures because of insurance requirements. In addition to systemic illnesses that limit their ability to care for themselves and possibly increase the risk of perioperative complications, many people have limited social or family support. Nurses are especially challenged to prepare these more complex patients for an early transition to home.

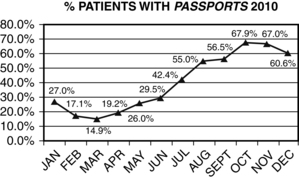

The Internet is another tool allowing patients and staff to share two-way information. Commercial and facility-developed assessment and educational tools allow patients to name their own time for providing preoperative health and demographic information. This does not preclude direct nursing interactions, but it provides a baseline from which to begin. Box 46-1 shows the work of one ambulatory surgery center to increase the use of such a tool using a quality improvement process.

BOX 46-1 Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement in the Ambulatory Surgery Center

Study objective

To increase the use of an online system for gathering patient preoperative information.

Background and reason for study

1. To obtain more accurate information when the patient has quiet time at home to concentrate on the questions

2. To reduce illegibility of patient and nurse writing

3. To reduce potential for error in transferring information from a preadmission sheet onto other chart pages (The Passport system transfers essential information such as allergies onto the admitting, anesthesia, and admitting forms.)

4. To reduce nursing time for people who have completed their Passport records ahead of the preadmission testing (PAT) call. The nurse has the data available to review and only ask questions where gaps or concerns are found.

5. To increase the ease of meeting CMS requirements for written and verbal notifications before the day of surgery

Action steps

| ACTION | RESPONSIBLE PARTY | METHOD |

|---|---|---|

| Engage all staff | Administrator, manager | Educate team, encourage all team members go online to create personal Passport record, brainstorm ideas to encourage patient and nurse use |

| Improve physician office assistance | Administrator | Create new flier and deliver to offices; ask for more direction of patients to web site by office |

| Increase e-mail notifications to patients | Administrator, schedulers, physician advocate | Encourage physician offices to secure e-mails and provide those email addresses to the ASC |

| Increase e-mail notifications to patients | Registrars | Ask patients on all business calls about e-mail address and their use; consider common scripting |

| Improve ease of web site access | Physician advocate | Meet with corporate marketing to seek better linkage |

| Improve ease of tool | Director | Remove redundant or unnecessary questions from Passport |

| Provide more encouragement to patients to use site | Registrar or PAT | Telephone assistance to get into the site, positive communication to patients |

| Encourage nurse use | Administrator | Communicate necessity to all staff members; provide reward and recognition |

| Team education | Director, administrator | Provide ongoing modules to team for understanding success factors; use graphs and support documents |

| Data sharing | Information systems support | Provide information on usage; track improvements |

| Tracking and team education | Administrators, nurse managers | Ongoing review of processes and ways to encourage patients to use the online system |

| Assignment change | Manager | Change in process to move a specific nurse into PAT role on weekly basis |

A report by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA)2 has identified major, intermediate, and minor clinical predictors of increased perioperative risk.

• Unstable coronary syndromes, such as acute or recent myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina, decompensated congestive heart failure, and severe dysrhythmias or valvular disease, are major predictors of perioperative risk.

• Intermediate risk factors include mild angina, prior MI determined with history or Q waves, compensated or prior heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency.

• Minor risks include advanced age, abnormal electrocardiogram results, dysrhythmias, low functional capacity, history of stroke, and uncontrolled hypertension.

These factors should be considered before any surgery, but especially before elective surgery that could wait until a more stable cardiac status can be attained. Active cardiac conditions for which the ACC and AHA recommend evaluation and treatment before elective surgery include: unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease, although these recommendations are not specific to ambulatory surgery. The same report identifies cardiac risk based on the type of procedure as low (less than 1%) for the following noncardiac surgeries: endoscopic and superficial procedures, cataract and breast surgery, and ambulatory surgery.3 The physician will determine the need for adjunctive preoperative cardiac assessment.

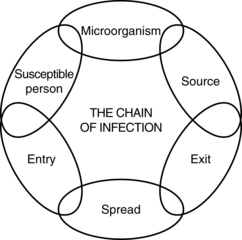

With the emphasis on safety in the perioperative period, involvement of the patient as fully as possible in safety practices is prudent. Boxes 46-2 and 46-3 provide information that can help to raise the patient’s understanding and consciously set expectations that the patient and family will be part of the overall safety plan. With the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms today, prevention of surgical site infection should be a key focus for all health care providers and the patient. Evidenced-based decisions are important to help reduce the potential for surgical site infection.

BOX 46-2 Ten Tips to Keep You Safe in the Outpatient Setting

1. Be sure that everyone who cares for you identifies you by asking you to say your name and birth date and by checking your name band.

2. If you have any questions or concerns, ask a team member. Ask a family member or friend to speak for you if you are not able to do so.

3. If you believe that you are not steady on your feet, please ask us to help you. We do not want you to fall.

4. When you are asked about the medicines you take, please tell us about every medicine. Be sure to include creams, vitamins, herbs, diet supplements, and all prescription and over-the-counter medicines, including street drugs.

5. Tell us about all your allergies. Include allergies to medicines, tape, latex, shellfish, and anything else you may have reacted to in the past.

6. If you have a new prescription given to you while you are here, be sure you know what it is for, how to take it, and any possible side effects.

7. If you have any questions about a test or procedure, please ask your nurse or doctor.

8. Ask team members who have direct contact with you if they have washed their hands. It is the best way to prevent the spread of germs, and we will be glad you asked.

9. Be sure you know and understand how to take care of yourself when you go home.

10. If you notice any other safety concerns, please tell a team member so we can work to make our outpatient center a safer place for all.

BOX 46-3 Ten Things You Can Do to Help Prevent a Surgical Site Infection

After your procedure

6. If you do not see your health care workers wash their hands before caring for you, speak up and ask them to do so. Do not be embarrassed; we want to keep you safe.

7. Keep any dressing, bandage, or cast clean and dry. If it gets wet and you have been instructed not to remove or change it, tell your physician immediately.

8. If antibiotics are prescribed, take all the pills and take them according to directions.

9. Wash your hands before touching your bandage or caring for catheters and drains and ensure that any other people helping you also wash their hands.

10. Do not put anything on your incision area that is not prescribed.

Source: Darouiche R, et al: Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis, N Engl J Med 362:18−26, 2010.

• Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (www.ahrq.gov)

• Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (www.aaahc.org)

• American Society of Anesthesiologists (www.asahq.org)

• American College of Surgeons (www.facs.org)

• Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia (www.sambahq.org)

• Institute for Healthcare Improvement (www.ihi.org)

• The Joint Commission (www.jointcommission.org)

• Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (www.sgna.org)

• American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (www.aana.com)

• Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (www.aorn.org)

• American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (www.aspan.org)

• Leapfrog Group (www.leapfroggroup.org)

• Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP; www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_ improvement_project)

The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses web site provides patient information on the following3:

• Preanesthetic interview and testing

• Expectations for the day of surgery

• What to expect in the preoperative holding area

• What to expect in the operating room

• What to expect in the postanesthesia care unit

• What to expect if you are going home on the day of surgery

Freestanding ASCs have an additional requirement imposed by the Centers of Medicare and Medicare Services (CMS).4 In ASCs that are Medicare certified, before surgery all patients, not just those covered by Medicare, must be provided with both verbal and written information about their rights and responsibilities, the ASC policy on advance directives, and any physician financial interest in the ASC. Three informational items must be provided to the patient before signing the consent for treatment. For clarity, the nurse should document the time of the notification and the time the consent is signed to verify that standards were met.

Admission of the patient

Current pressure from government, industry, consumer, and other groups to reduce medical errors and improve overall patient safety is demonstrated by a list of the most common sentinel events reviewed by The Joint Commission. Their sentinel event data compiled from 1995 through 2010 demonstrates that wrong site surgery remains one of the top three reviewed events in the last few years, ranking number one in 2008 and 2009 and ranking third in 2010.5 Although these events represent both inpatient and outpatient surgeries in all types of settings, the lesson remains that this is a serious opportunity for error. Nurses must enforce strict policies regarding site marking and timeout procedures in all cases all of the time; this includes preoperative anesthesia blocks as well as surgical and endoscopic procedures.

Fasting before surgery

Fasting requirements as defined per facility by the department of anesthesia are decidedly more lenient that in the past. Traditional guidelines for “nothing after midnight” have been challenged and are now rarely used. The American Society of Anesthesiologists advocates the following fasting guidelines for elective procedures that involve anesthesia and sedation.6

| INGESTED MATERIAL | MINIMUM FASTING HOURS |

|---|---|

| Clear liquids | 2 |

| Breast milk | 4 |

| Infant formula | 6 |

| Light meal (e.g., toast and clear liquid) | 6 |

| Nonhuman milk | 6 |

| Meal with fried or fatty foods or meat | 8 or more |

Diagnostic testing

Required preoperative diagnostic tests vary widely from one institution to another and are a matter both of clinical judgment by individual physicians and the policies set by the medical board that administers the ambulatory surgical program. Current trends are toward performing no or only essential diagnostic tests that are aimed at providing the basic information necessary for safe anesthesia and surgical interventions. The American Society of Anesthesiologists supports that preoperative tests may be useful in the preanesthesia evaluation; however, no routine laboratory or diagnostic screening is necessary. Routine refers to tests performed without regard to clinical indications for an individual patient. Screening refers to efforts to detect disease in asymptomatic patients in unselected populations.7

Preoperative goals

An important way to provide a safe experience for the ambulatory patient is to consistently apply safety policies in the same manner for all patients. A surgical safety checklist like the one developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) provides a method to document all essential areas of care at three points in the continuum of patient care: before anesthesia induction, before the skin incision, and before the patient leaves the operating room.8 The tool that can be downloaded from the WHO web site is intended as a baseline, and modifications are encouraged to fit the specific types of care provided in a surgical setting.

Intraoperative period

Anesthesia considerations

Anesthesia for the ambulatory surgical patient incorporates the traditional goals of adequate analgesia, muscle relaxation, amnesia, and, in the event of general anesthesia, loss of consciousness to accomplish the intended procedure. Because the ambulatory surgical patient is discharged soon after the procedure, the anesthesia plan should promote reduced postoperative hangover and complications. Topical, regional, and local techniques are favored by many clinicians because the patient does not lose consciousness, can usually be discharged sooner after the procedure, and often has prolonged pain relief at the operative site or extremity.

Postanesthesia period

The American Society of Perianesthesia Nurses has published a position statement that any fasttracking plan should be a collaboration of the anesthesiology department and perianesthesia services. Guidelines should include appropriate patient selection, preoperative education of the patient and family, appropriate selection and management of anesthetic agents, assessment criteria used to determine readiness for bypassing PACU care, discharge criteria, and monitoring and reporting of patient outcomes.9

Postanesthesia care unit

The goal of adequate patient comfort is supported when the patient knows before surgery that the nurse is concerned about and eager to provide adequate pain relief. Patients should be encouraged to discuss their usual tolerance for pain and should not be judged in that regard based on the attitudes and prior experiences of the staff. The use of an objective pain scale helps in determining the patient’s need for intervention, and patients should be educated on that scale before procedures for comparison. They should also know that although total absence of postoperative discomfort may not be a realistic goal, acute pain should be reported and treated. Patient comfort, supported by positive thinking, general comfort measures, and oral analgesics, is one of the criteria with which eventual discharge readiness is measured, and this goal must be addressed in the early stages of recovery.

Progressive or phase ii care

Most often, the phase II unit is where patients reunite with family members or the responsible adults who will accompany and care for them at home. Early reunion should be encouraged, and nurses in this setting must purposefully involve the patient’s support people. The responsible adult may need to learn how to care for the patient’s physical needs, such as changing a dressing, observing extremity circulation, or emptying drains. Encouraging a return demonstration of manual skills or having the caretaker repeat information is a good way to reinforce learning and to evaluate the person’s ability to provide support. The nurse should focus on the information specifically needed to provide care and not divulge extraneous health information.

Medication reconciliation is a focus of the National Patient Safety Goals and is the responsibility of the physician. The patient’s list of usual medications should be compared and reconciled with any medications given in the center that have a prolonged effect into the home recuperative period and with medication prescriptions given. Reconciliation is a review of the medications to identify contraindications, misunderstandings, and potential for duplication of medication. For example, consider the patient who routinely takes Percocet at home who is given a prescription for acetaminophen–oxycodone. Without review and reconciliation of the lists with the patient, a duplication could occur with serious ramifications.

Postdischarge follow-up

In many communities, the standard of care is that patients are telephoned within the next few days after surgery to ascertain their clinical condition, safety, and comfort level. Such a contact can serve as a valuable resource for patients who may have symptoms that should be evaluated by their physicians or questions about which they are embarrassed or reluctant to telephone and ask their physicians. Not only is the patient’s safety and medical condition supported, but the nursing staff also can identify the effectiveness of current modes of care. Other reasons for a postdischarge call include promotion of the facility’s caring attitude, identification and reduction of medicolegal issues, marketing, the meeting of accrediting and regulatory standards, and closure and a sense of job satisfaction for the nurses.

In addition, Joint Commission standards now require a 1-year follow-up to identify infections in patients who have had implantable devices placed during their procedures. This is another imposed regulation that must be met to help reduce the potential for surgical site infections by understanding and investigating events.10

1. Dorothea Orem’s Self Care Theory. available at http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/self_care_deficit_theory.html, March 18, 2011. Accessed

2. Fleisher LA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. available at: http://www.circ.ahajournals.org/content/116/17/e418.full?sid=31fe5f4f-448a-48d3-b6bc-b9bd5ec2527e March 17, 2011. Accessed

3. American Society of Perianesthesia Nurses: ASPAN patient information. available at: www.aspan.org, March 10, 2011. Accessed

4. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: 42 CFR Part 416. Washington, DC; 2008.

5. The Joint Commission, Office of Quality Monitoring: Most frequently reviewed sentinel event categories by year. available at: www.jointcommission.org, March 18, 2011. Accessed

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc: Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. Anesthesiology.2011;114:495–511.

7. American Society of Anesthesiologists: Statement on routine preoperative laboratory and diagnostic screening: approved by House of Delegates October 15, 2003, last amended October 22, 2008. available at: www.ASAHQ.org, March 16, 2011. Accessed

8. World Health Organization: The WHO surgical safety checklist 2009. available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/tools_resources/en/index.html, March 18, 2011. Accessed

9. American Society of Perianesthesia Nurses: Position statement of fast tracking. available at: https://www.aspan.org/Portals/6/docs/ClinicalPractice/PositionStatement/6-Fast_Tracking.pdf, March 18, 2011. Accessed

10. The Joint Commission: Comprehensive (CAMAC) accreditation manual for ambulatory care. available at: http://www.jcrinc.com/Joint-Commission-Requirements/Ambulatory-Care/, 2009. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: The Joint Commission; April 2, 2012. Accessed