1 Cardiovascular system

Anaesthesia and cardiac disease

Previous ischaemia

Important risk studies

Investigations

ECHO. Ejection fraction, wall motion and valve abnormalities.

Technetium-99m scan. Similar to thallium scan but underperfused areas show as hot spots.

General anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery

Choice of anaesthetic technique or volatile agent has no proven effect on cardiac outcome. Aim to optimize myocardial oxygen balance (Table 1.1).

| Supply | Demand |

|---|---|

| Coronary perfusion | Preload (LVEDP) |

| O2 content | Afterload (SVR) |

| Heart rate | Heart rate |

| Contractility |

Premedication

Aspirin. Although aspirin increases the risk of bleeding complications, it does not increase the severity level of the bleeding complication. A meta-analysis has shown that aspirin withdrawal was associated with a three-fold higher risk of major cardiac events (Biondi-Zoccai et al 2006).

Anaesthetic

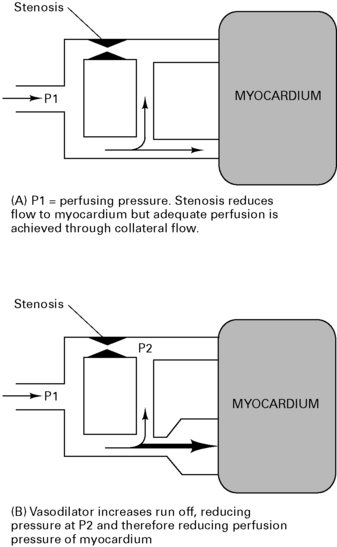

Volatiles. Enflurane and halothane both decrease coronary blood flow, but isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane increase coronary blood flow and maintain LV function in normotensive patients. Tachycardia with isoflurane increases myocardial work, but this is minimal with balanced anaesthesia. There is some concern that isoflurane may cause coronary steal (Fig 1.1) but it is thought not to do so as long as coronary perfusion pressure is maintained. There is growing evidence that isoflurane has myocardial protective properties, limiting infarct size and improving functional recovery. This mechanism mimics ischaemic pre-conditioning and involves the opening of ATP-dependent K+ channels causing vasodilation and preservation of cellular ATP supplies. Desflurane and sevoflurane probably have similar but less marked cardioprotective effects.

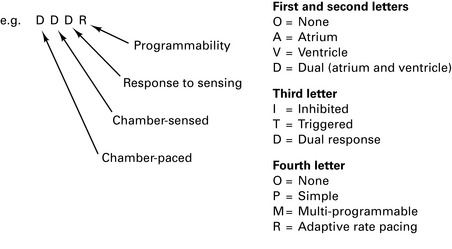

Pacemakers

There are 200 000 patients with implanted pacemakers in the UK.

Automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillators (AICDs)

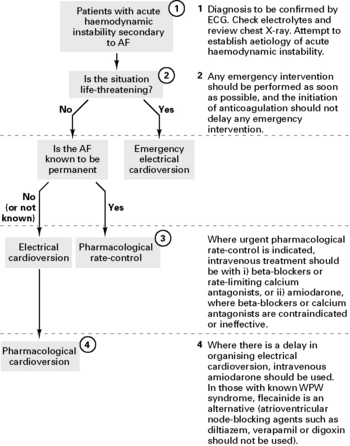

Atrial Fibrillation: the Management of Atrial Fibrillation

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, June 2006

Antithrombotic therapy for acute-onset atrial fibrillation (AF)

For patients with acute AF who are receiving no, or only sub-therapeutic anticoagulation therapy:

Anaesthetic considerations for heart surgery

Ischaemic heart disease

Rate pressure product (RPP) = heart rate × systolic pressure. Aim to maintain value at below 12 000.

Endocarditis prophylaxis

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, March 2008 (http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG64PIEQRG.pdf)

Summary

Risk factors for the development of infective endocarditis

Guidelines for the Prevention of Endocarditis

Report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2006

Dental procedures

Prophylaxis is only recommended for high-risk patients

ACC/AHA. Guideline Update for Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery – Executive Summary. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1052-1064.

Agnew N.M., Pennefather S.H., Russell G.N. Isoflurane and coronary heart disease. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:338-347.

Allen M. Pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:883-890.

Biccard B.M. Peri-operative β-blockade and haemodynamic optimization in patients with coronary artery disease and decreasing exercise tolerance. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:60-68.

Biondi-Zoccai G.G., Lotrionte M., Agostoni P., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspiring among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2667-2674.

British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Guidelines for the Prevention of Endocarditis. Report of a Working Party, 2006 http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/dkl121v1.

Chassot P.G., Delabays A., Spahn D.R. Preoperative evaluation of patients with, or at risk of, coronary artery disease undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:747-759. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG036niceguideline.pdf.. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence

De Hert S.G. Preoperative cardiovascular assessment in noncardiac surgery: an update. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:449-457.

Fleisher L.A., Beckman J.A., Brown K.A., et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1971-1996.

Gould F.K., Elliott T.S.J., Foweraker J., et al. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:1035-1042.

Howell S.J. Peri-operative β-blockade. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:161-164.

Howell S.J., Sear J.W., Foëx P. Hypertension, hypertensive heart disease and perioperative cardiac risk. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:570-583.

Mahar L.J., Steen P.A., Tinker J.H., et al. Perioperative myocardial infarction in patients with coronary artery disease with and without aorta-coronary bypass grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:533-537.

Mangano D.T., Browner W.S., Hollenberg M., et al. Association of perioperative myocardial ischaemia with cardiac morbidity and mortality in men undergoing non-cardiac surgery. The study of the Perioperative Ischaemia Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1781-1788.

Mythen M. Pre-operative coronary revascularization before non-cardiac surgery: think long and hard before making a pre-operative referral. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1045-1050.

Newby D.E., Nimmo A.F. Prevention of cardiac complications of non-cardiac surgery: stenosis and thrombosis. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:628-632.

NICE. Atrial Fibrillation: the Management of Atrial Fibrillation, 2006. June www.nice.org.uk/CG036NICEguideline

NICE. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis against Infective Endocarditis in Adults and Children Undergoing Interventional Procedures, 2008. March www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG64PIEQRG.pdf

Moppett I., Sharjar M. Transoesophageal echocardiography. Br J Anaesth CEPD Reviews. 2001;1:72-75.

Ng A., Swanevelder J. Perioperative echocardiography for non-cardiac surgery: what is its role in routine haemodynamic monitoring? Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:731-733.

POISE study group, Devereaux P.J., Yang H., Yusuf S., et al. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery (POISE trial): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839-1847.

Roscoe A., Strang T. Echocardiography in intensive care. Cont Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:46-49.

Salukhe T.V., Dob D., Sutton R. Pacemakers and defibrillators: anaesthetic implications. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:95-104.

Cardiac surgery

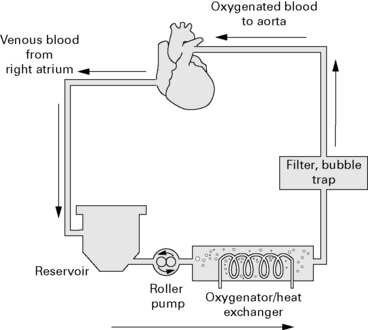

Cardiopulmonary bypass

Drug pharmacokinetics

Anaesthesia for cardiac surgery

Monitoring

CVP. Monitoring through multi-lumen line.

Pulmonary artery catheter. Controversial but may improve outcome in selected patients.

Sequence of events in CABG surgery

Anaesthesia. Invasive monitoring and induction of general anaesthesia.

Heparin is administered into a central vein and ACT checked prior to commencing CPB.

Pericardial stretching during cardiac manipulation may impair venous return and lower BP.

Nitrous oxide is discontinued to avoid enlargement of any air emboli (or not used at all).

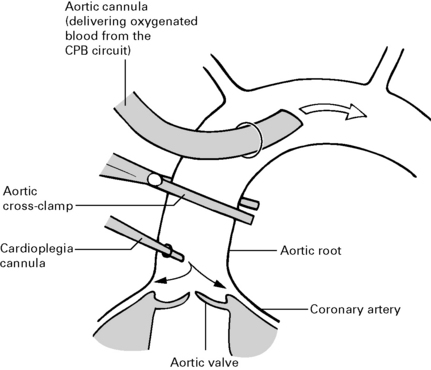

CPB is then initiated. Ventilation is stopped when full bypass is established. The aorta is clamped proximal to the cannula and cardioplegia solution infused into the aortic root where it perfuses the coronary arteries causing asystole (Fig. 1.5).

Weaning from bypass

Difficulty occurs usually due to ischaemia following aortic cross-clamping or myocardial stunning.

Intra-aortic balloon-pump counterpulsation

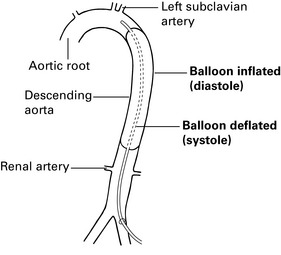

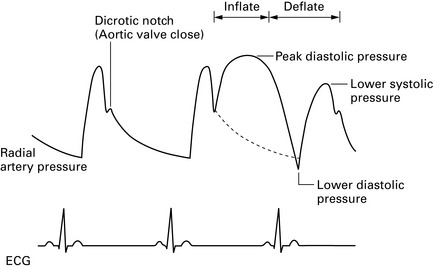

This is used as a mechanical assist device for the failing myocardium. The intra-aortic balloon is placed in the aortic arch/early descending thoracic aorta via the femoral artery so that the tip lies distal to left subclavian artery, but is not occluding renal arteries (Fig. 1.6).

Neurological monitoring and protection

Monitoring

Unmodified EEG. Some evidence for correlation with outcome.

Processed EEG. Easier to interpret.

Transcranial Doppler. Research tool. Correlates with neuroinsults.

Jugular bulb O2 saturation. Desaturation is common but significance is not known.

Regional cerebral blood flow. Research tool.

Cerebral oximetry. Non-invasive and only monitors small regions.

Protection

Barbiturates: may protect in high doses (>30 mg/kg) but conflicting studies.

Steroids: no evidence for benefit.

Death Following a First Time, Isolated Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

A report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2008

Recommendations

Non-elective, urgent, in-hospital cases

Perioperative management and postoperative care

Communication, continuity of care and consent

Multidisciplinary review and audit

Cornelissen H., Arrowsmith J.E. Preoperative assessment for cardiac surgery. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care & Pain. 2006;6:109-113.

Feneck R.O. Cardiac anaesthesia: the last 10 years. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1171-1177.

Hett D.A. Anaesthesia for off-pump coronary artery surgery. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care & Pain. 2006;6:60-62.

Krishna M., Zacharowski K. Principles of intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care & Pain. 2009;9:24-28.

Machin D., Allsager C. Principles of cardiopulmonary bypass. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care & Pain. 2006;6:176-181.

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Death Following a First Time, Isolated Coronary Artery Bypass Graft, 2008 www.ncepod.org.uk/2008report2/Downloads/CABG_summary.pdf.

Royse C.F. High thoracic epidural anaesthesia for cardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:84-87.

Russell I.A., Rouine-Rapp K., Stratmann G., et al. Congenital heart disease in the adult: a review. Anesth Analg. 2006:102-694. 102–723

Scott T., Swanevelder J. Perioperative myocardial protection. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care & Pain. 2009;9:97-101.

Shaaban Ali M., Harmer M., Kirkham F. Cardiopulmonary bypass and brain function. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:365-372.

Major vascular surgery

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

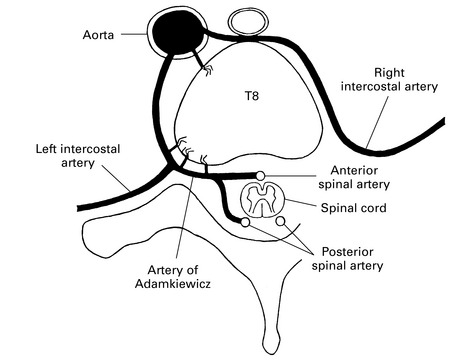

Arterial supply to the spinal cord

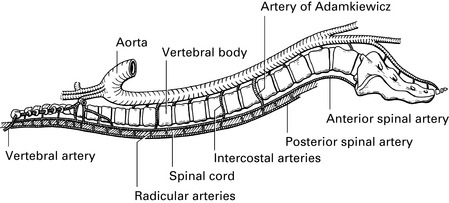

The major arterial supply to the spinal cord is a single anterior spinal artery lying in the anterior median fissure of the cord and two posterior spinal arteries located just medial to the dorsal roots. The anterior spinal artery is fed from several sources (Figs 1.8, 1.9):

Spinal cord injury

Augoustides J.G. The year in cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia: selected highlights from 2008. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:1-7.

Djurberg H., Haddad M. Anterior spinal artery syndrome. Anaethesia. 1995;50:345-348.

GALA Trial Collaborative Group. General anaesthesia versus local anaesthesia for carotid surgery (GALA): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:2132-2142.

Hebballi R., Swanevelder J. Diagnosis and management of aortic dissection. Contin Edu Anaesth, Criti Care & Pain. 2009;8:14-18.

Leonard A., Thompson J. Anaesthesia for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Contin Edu Anaesth, Criti Care & Pain. 2008;8:11-15.

Sloan T.B. Advancing the multidisciplinary approach to spinal cord injury risk reduction in thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:555-556.

Spargo J.R., Thomas D. Local anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy. Contin Edu Anaesth, Criti Care & Pain. 2004;4:62-65.

Tuman K.J. Anesthetic considerations for carotid artery surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000. Review Course Lectures (Suppl)

Hypotensive anaesthesia

Contraindications

Effects of hypotension

CVS. Reduced diastolic pressure reduces coronary perfusion pressure.

CNS. Loss of cerebral autoregulation <50 mmHg. Risk of ischaemia in the presence of hypocapnia.

Techniques of induced hypotension

Direct-acting vasodilators

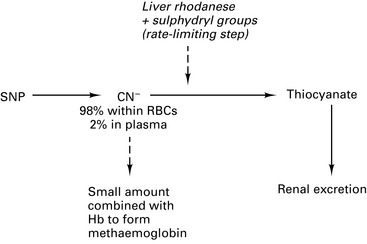

The very short half-life of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) enables rapid reduction in BP and equally rapid restoration (2–4 min). It dilates resistance and capacitance vessels. Vasodilation causes raised intracranial pressure and SNP should not be used in neurosurgery until the cranium has been opened. SNP increases aortic flow, increasing shearing pressure; therefore β-blockers may need to be used in addition. Start at 0.3 μg.kg−1.min−1 to limit cyanide toxicity (max. 8 μg.kg−1.min−1). Base deficit >–7 mmol.L−1 is suggestive of CN− toxicity. Sodium thiosulphate reduces CN– levels by providing sulphydryl groups at the rate-limiting step (Fig. 1.10).

(ventilation/perfusion) mismatch and ↓ FRC. Volatile agents may further impair hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. May need Fi

(ventilation/perfusion) mismatch and ↓ FRC. Volatile agents may further impair hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. May need Fi