Chapter 15 Cardiovascular, respiratory, haematological, neurological and gastrointestinal disorders in pregnancy

CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS IN PREGNANCY

Management during childbirth

The risks and management of specific cardiac conditions are summarized in Table 15.1.

| Condition | Pregnancy Risks | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial septal defect | Rarely causes problems | Nil specific after exclusion of other secondary complications |

| Ventricular septal defect | Small defects rarely cause problems | Avoid hypertension, endocarditis prophylaxis |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | Small shunts rarely problematic | Exclude pulmonary hypertension |

| Coarctation of aorta | Corrected, few problems; uncorrected, maternal mortality (15%) | Prevent hypertension, use epidural in labour |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension | Maternal mortality of 50% |

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM IN PREGNANCY

Treatment of a pulmonary embolus during pregnancy consists of unfractionated heparin (UH), initially intravenously (40 000 U/day by continuous infusion in normal saline) to obtain a concentration of 0.6–1.0 U/mL. Once full heparinization has been obtained for 3–7 days, the infusion may be replaced by calcium heparin given subcutaneously. A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is treated either with UH if delivery or surgery is imminent, or low molecular weight heparin (LWMH) given subcutaneously. UH is substituted for LMWH 24–36 hours prior to delivery. UH is suspended once labour is established or 6 hours before surgery, and recommenced 2–6 hours after vaginal or caesarean delivery. If the woman has a high risk of VTE antenatally (includes recurrent VTE, previous idiopathic VTE or previous VTE and a strong family history of VTE) she may be given LMWH prophylaxis throughout pregnancy and for 6 weeks postpartum (see also postpartum thromboembolism, p. 186).

ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID SYNDROME

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is associated with early-onset pre-eclampsia, intrauterine fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, miscarriage, fetal death and venous thromboembolism. Diagnosis requires at least one of the clinical criteria and one of the laboratory criteria (see Box 15.1). Women who have suffered from clinical complications should be screened and referred for specialist evaluation.

ANAEMIA IN PREGNANCY

THALASSAEMIA AND HAEMOGLOBINOPATHIES

The haemoglobinopathies (thalassaemia and sickle cell disease) (Box 15.2) are inherited disorders of haemoglobin. They are autosomal recessive defects, and characterized by reduced production of one or more of the chains of globin that make up haemoglobin. Carriers (who have only one affected globin locus) remain healthy throughout life. People who are homozygous or doubly heterozygous have haemoglobin disorders of varying clinical severity.

Issues for antenatal care include:

Antenatal or preconceptual screening

If a woman’s screening is abnormal, then screening of her partner should be performed.

RED CELL ALLOIMMUNIZATION

Investigations

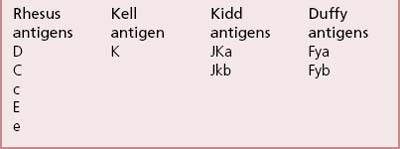

Antigens that stimulate antibodies known to cause clinically significant haemolytic disease are shown in Box 15.3.

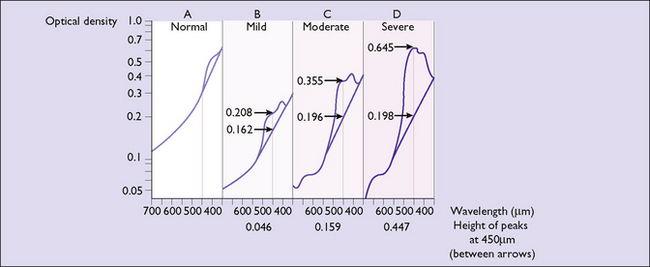

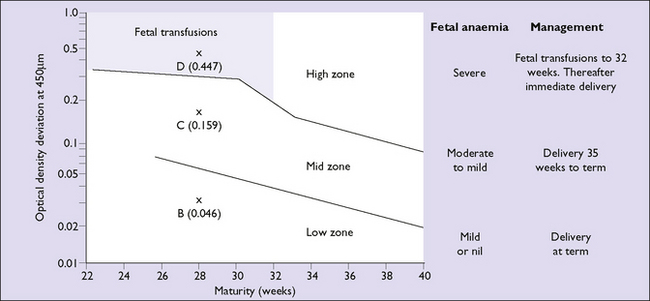

Indirect methods of screening for moderate to severe fetal anaemia are available. Spectrophotometric examination of amniotic fluid is performed to identify the presence of bilirubin. A sample is collected at amniocentesis and bilirubin is measured as a change in optical density at 450 nanometres (OD 450) (Fig. 15.1). The OD 450 level is then interpreted using a curve (Liley, Queenan or Robertson) that predicts the degree of anaemia based on the amount of haemolysis at a given gestation (Fig. 15.2). Depending on the gestational age at which the OD 450 reaches a critical level, either delivery or cordocentesis (fetal blood sampling) with intrauterine transfusion can be arranged. The OD 450 is most widely used in Rh D alloimmunized pregnancies and may underestimate the degree of anaemia in Kell immunization. In Kell immunization both haemolysis and suppression of red cell production contribute to anaemia.