CHAPTER 13 CARDIOVASCULAR PATHOLOGY

INTRODUCTION

DIAGNOSTIC ENDOMYOCARDIAL BIOPSY

CARDIOMYOPATHIES

Table 13.1 Simplified classification of pediatric cardiomyopathies (Richardson et al 1996)

| Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

Histopathological features of cardiomyopathies on biopsy

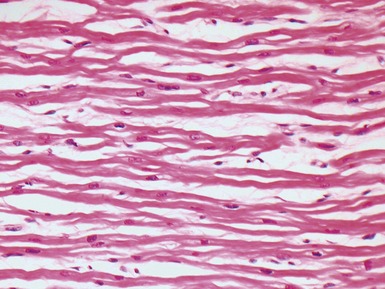

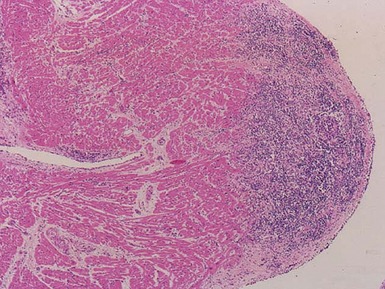

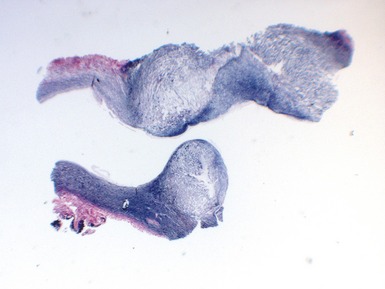

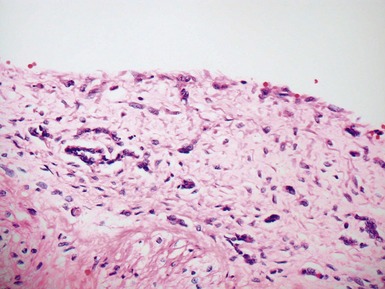

Dilated cardiomyopathy (Figs 13.1–13.4)

Fig 13.3 Photomicrograph of an endomyocardial biopsy from the same case as Fig 13.2. The myocytes show variation in size, as do their nuclei. There is mild interstitial fibrosis and the endocardium shows mild to moderate, fibroelastic thickening. (Elastic van Gieson)

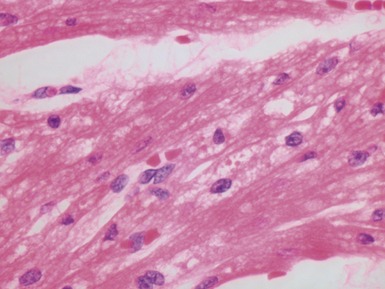

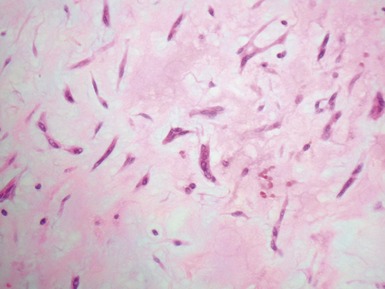

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Figs 13.5, 13.6)

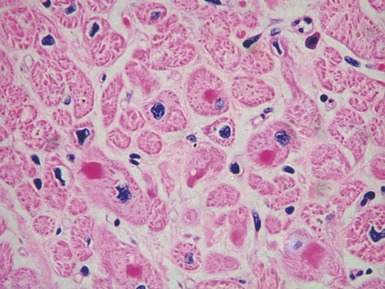

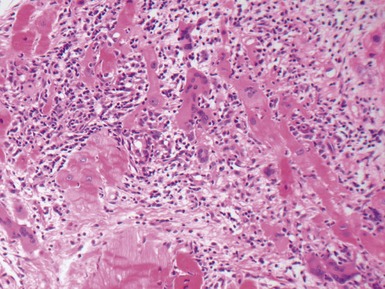

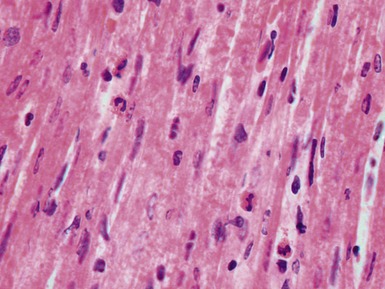

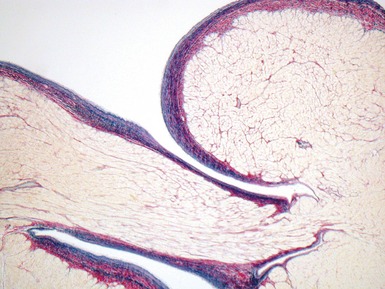

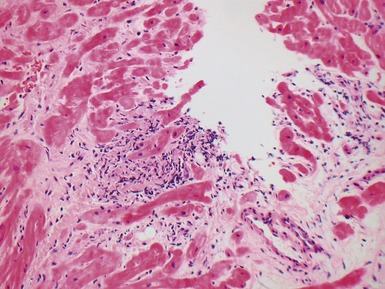

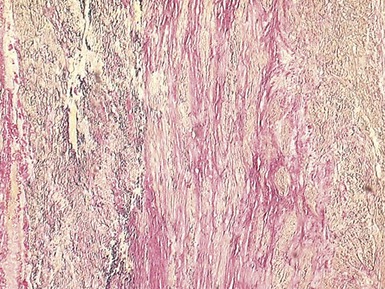

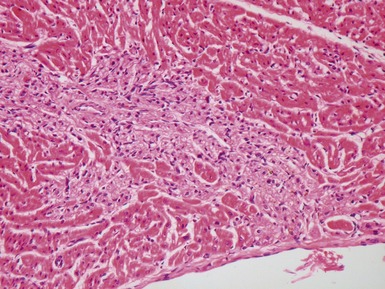

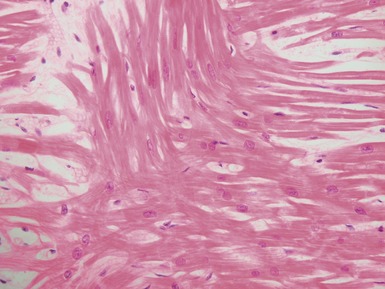

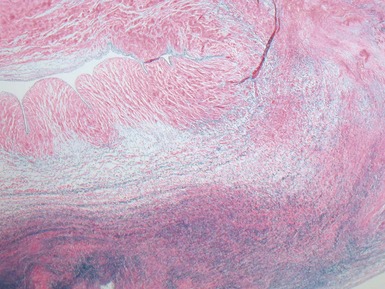

Fig 13.5 Photomicrograph of heart from an 11-year-old boy with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. There is readily apparent myocyte disarray. Disarray is also usually evident at a macroscopic level where the muscle bundles are whorled, and also at the ultrastructural level where the myofilaments are disorganized.

| Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| Normal heart near the insertion of the septum into the ventricular free walls |

| Congenital heart disease, particularly hypoplastic left heart |

| Previous biopsy site on endomyocardial biopsy (see section on post-transplant biopsy) |

| Adjacent to myocardial scars |

Restrictive cardiomyopathy

Other forms of cardiomyopathy

VIRAL MYOCARDITIS

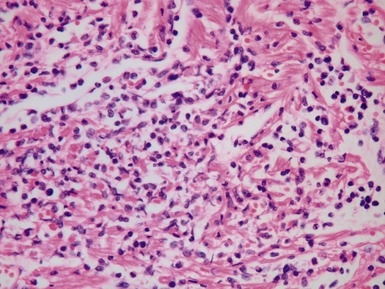

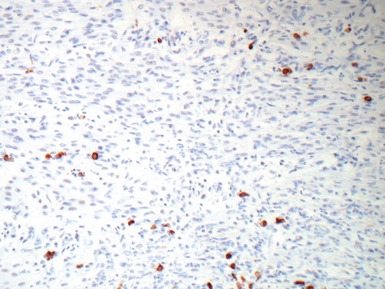

Histopathological features (Figs 13.9–13.13)

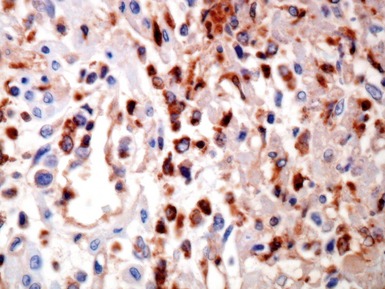

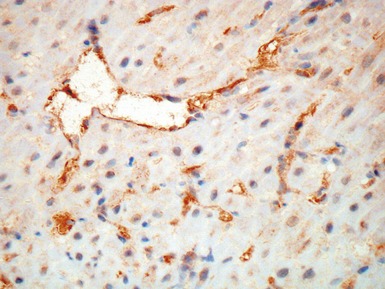

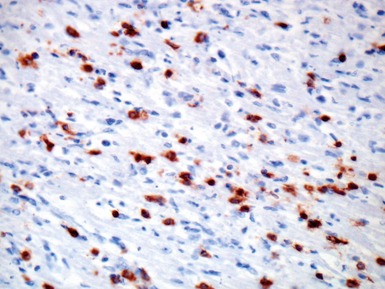

Fig 13.10 Same case as Fig 13.9 stained with anti-CD3 antibody. There are large numbers of positive T-cells in the myocardium.

NON-VIRAL MYOCARDITIS

Giant cell myocarditis (Laufs et al 2002, Das et al 2006)

ASSESSMENT OF THE EXPLANTED HEART

INTRODUCTION

CARDIOMYOPATHIES IN THE EXPLANTED HEART

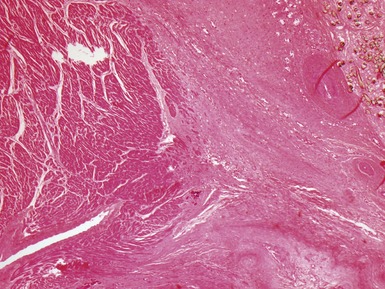

Fig 13.20 Same case as Fig 13.19, showing the cannula insertion site at the left ventricular apex. There is dense myocardial fibrosis. Dark flecks of dystrophic calcification are seen at the junction with the myocardium. Suture material is evident on the right. Inflammation is minimal in this case.

Histopathological features of cardiomyopathies in explanted hearts

Dilated cardiomyopathy

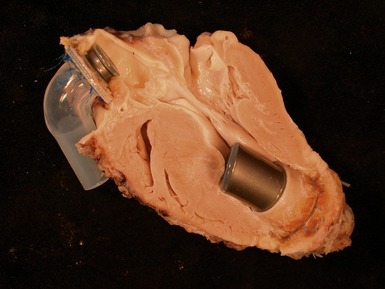

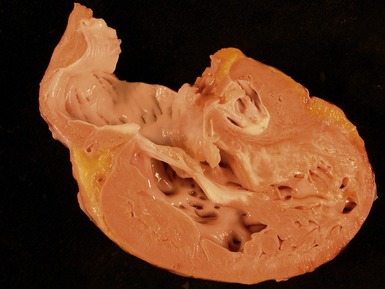

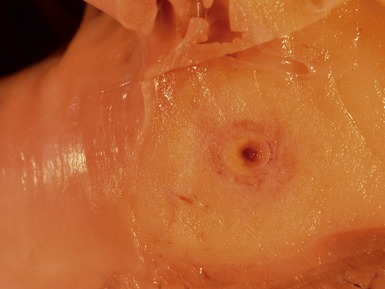

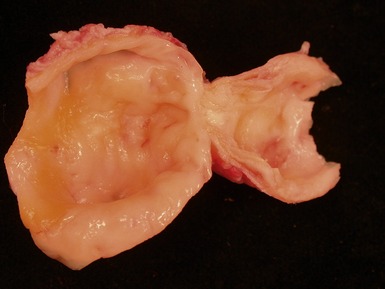

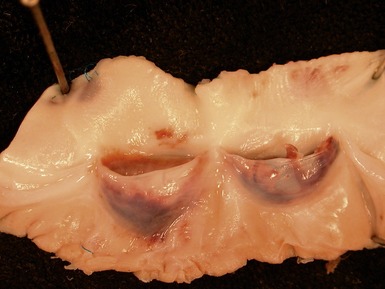

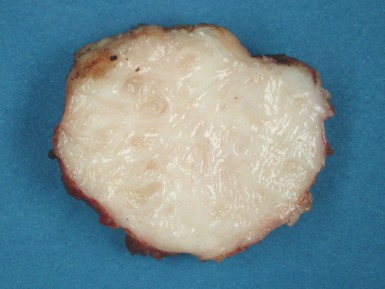

Macroscopic features (Fig 13.21)

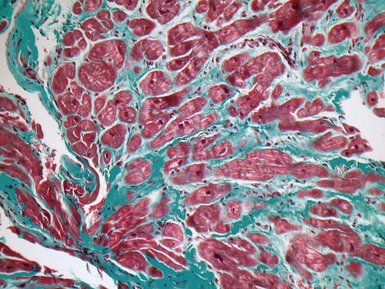

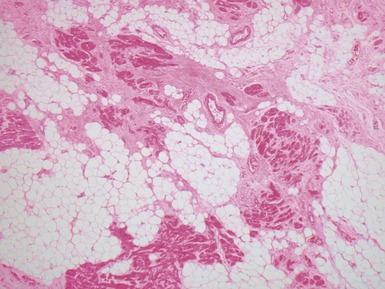

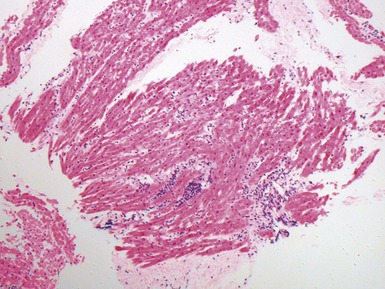

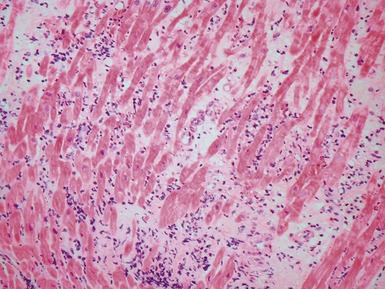

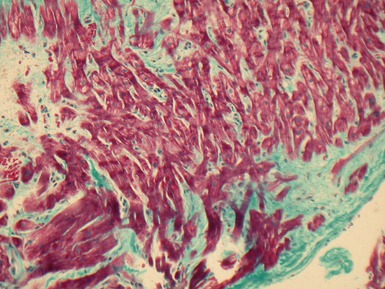

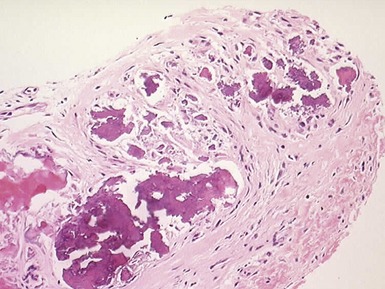

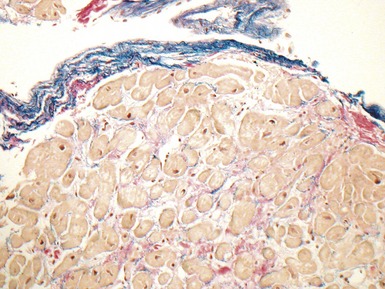

Microscopic features (Figs 13.22–13.24)

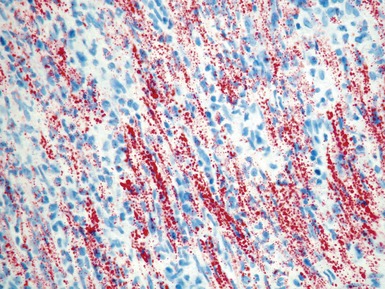

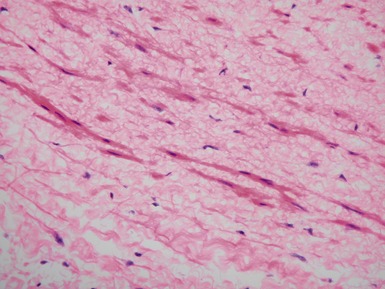

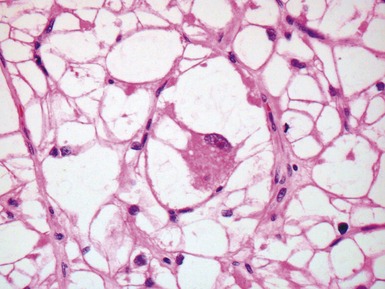

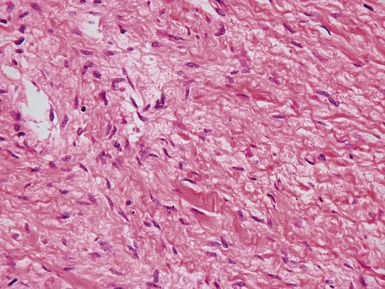

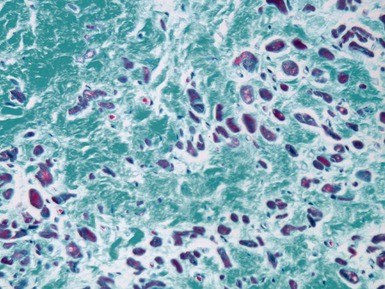

Fig 13.22 Photomicrograph of heart from a 4-year-old boy with dilated cardiomyopathy. Section of left ventricular myocardium of explanted heart shows extensive interstitial fibrosis with myocyte dropout. (Masson trichrome)

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Macroscopic features (Fig 13.25)

MITOCHONDRIAL CARDIOMYOPATHIES

ARRHYTHMOGENIC RIGHT VENTRICULAR CARDIOMYOPATHY

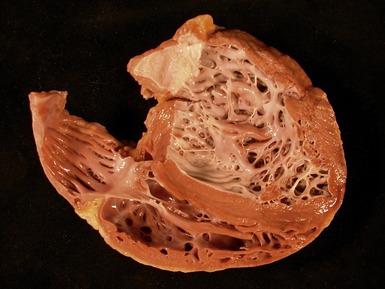

NON-COMPACTION OF THE VENTRICULAR MYOCARDIUM

EXPLANTED HEARTS WITH CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

Technical considerations

Common operations in congenital heart disease

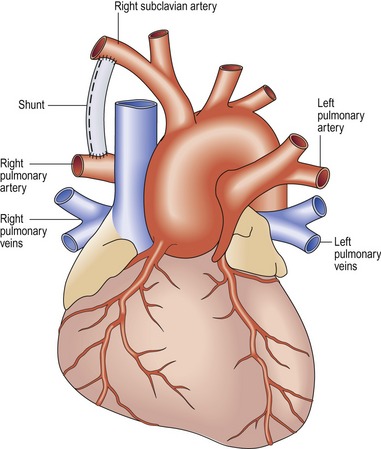

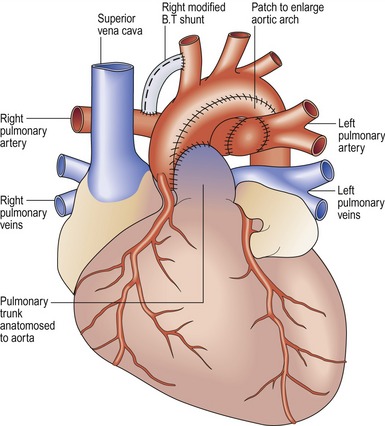

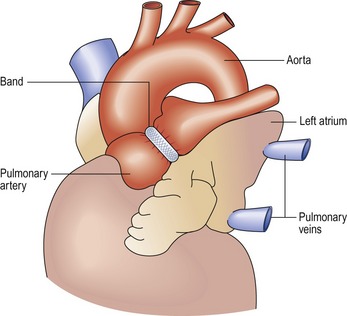

Modified Blalock–Taussig shunt (Fig 13.31)

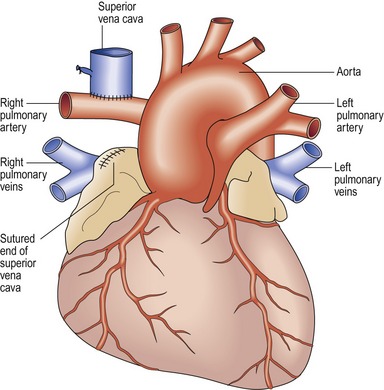

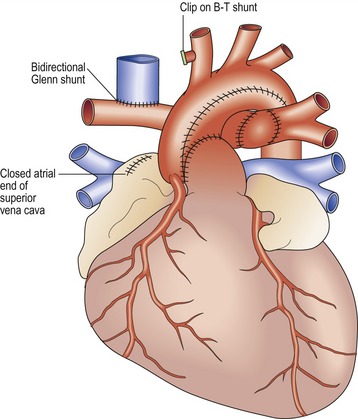

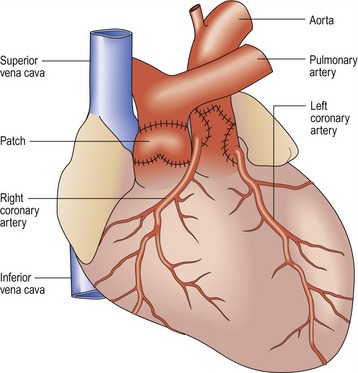

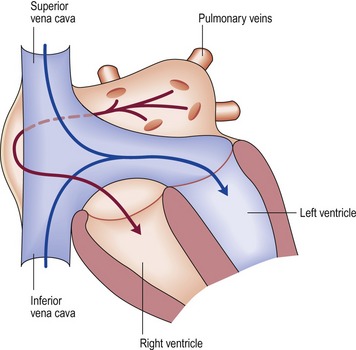

Bidirectional Glenn shunt (Fig 13.33)

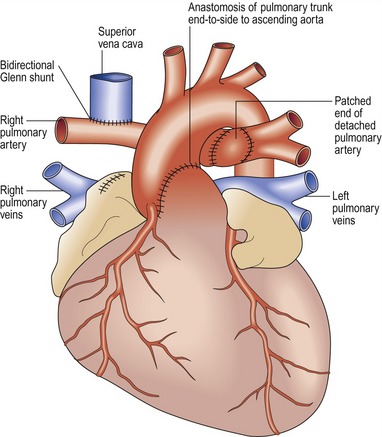

Damus–Kaye–Stansel (DKS) procedure (Fig 13.34)

Norwood procedure

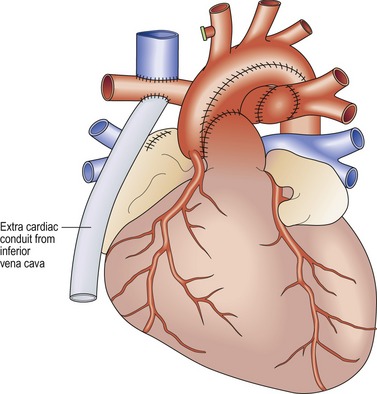

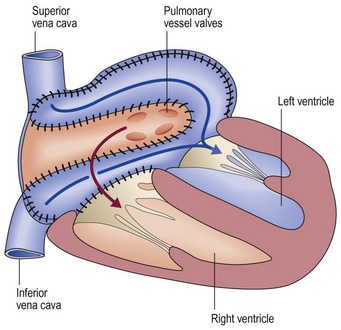

Fontan procedure

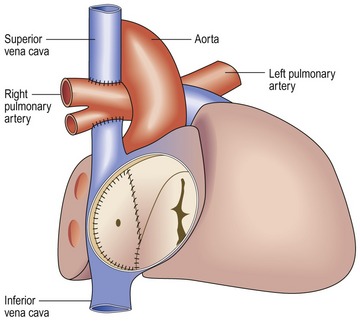

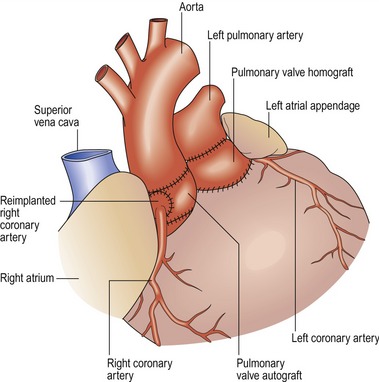

Arterial switch operation (Fig 13.40)

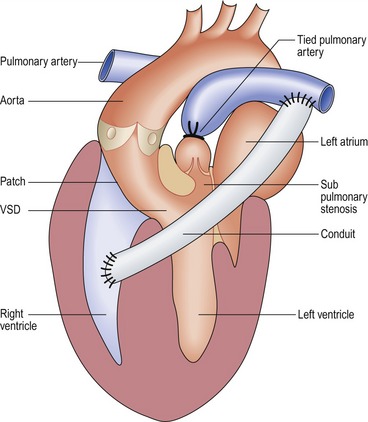

Rastelli operation (Fig 13.41)

Some specific conditions

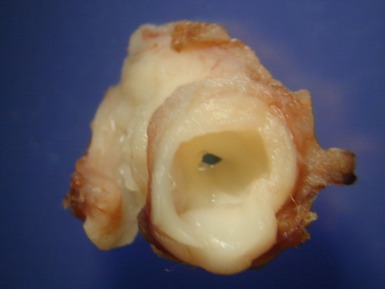

Hypoplastic left heart

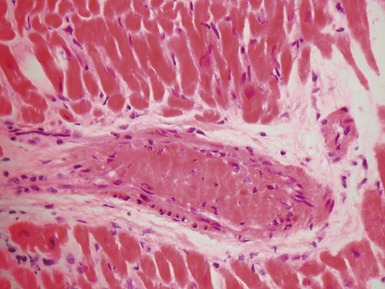

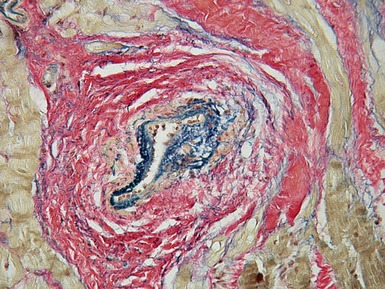

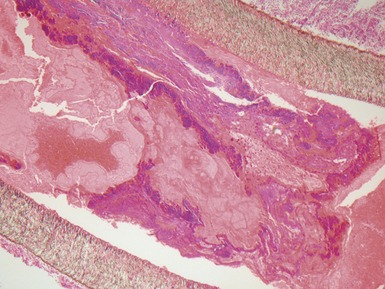

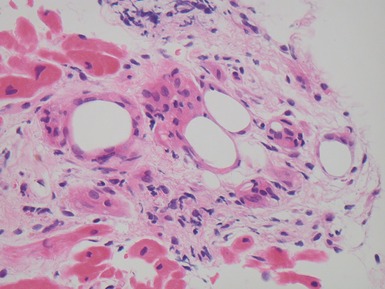

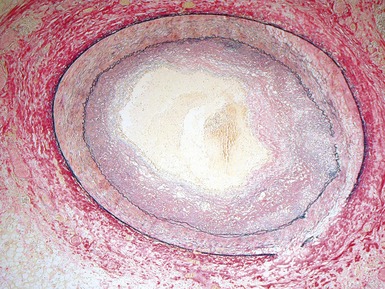

Fig 13.47 Same case as Fig 13.33. Photomicrograph of a section of left ventricular myocardium including intramyocardial arteries. The arteries show increased adventitial collagen, fibrosis of their muscular media and near occlusive concentric intimal fibroelastic proliferation. These changes suggest communication between the left ventricular cavity and the coronary arteries. (Elastic van Gieson)

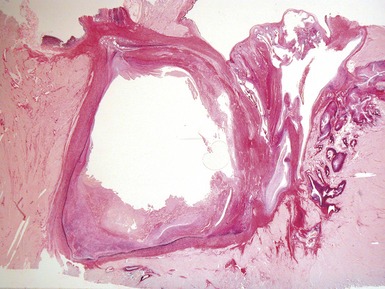

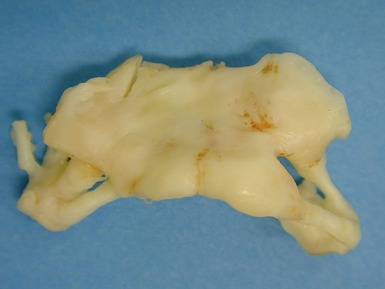

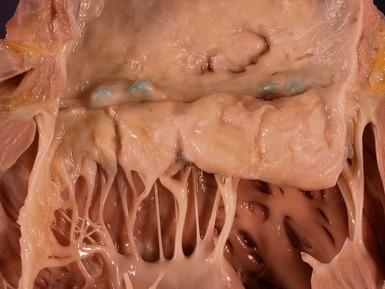

Tetralogy of Fallot

Fig 13.48 Explanted heart from a 14-year-old with Tetralogy of Fallot who underwent closure of the VSD and insertion of a RV-PA conduit at age 4 years. Developed heart block and increasing left ventricular failure. Coronal section through the patched VSD showing the wrinkled patch covered by dense endocardial fibroelastic tissue on both sides. The fibrous tissue encroaches on the region of the bundle of His at the apex of the muscular interventricular septum.

FAILURE OF THE CARDIAC GRAFT AND ITS REMOVAL AT A SECOND TRANSPLANT OPERATION

Clinical features

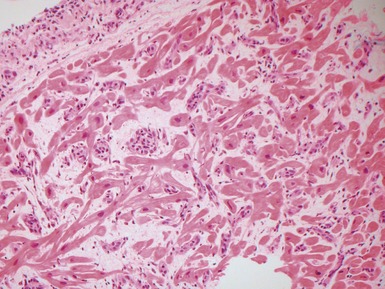

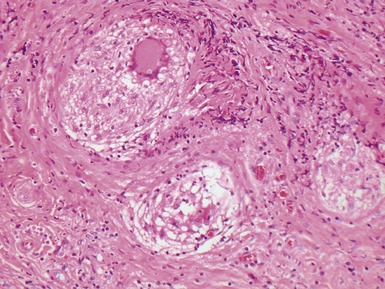

Histopathological features

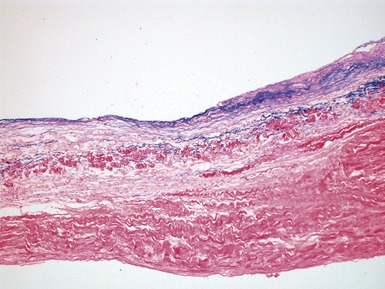

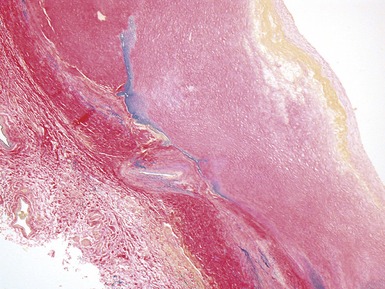

Fig 13.52 Same vessels as in Fig 13.51. Photomicrograph showing increased adventitial collagen. The tunica media is fibrotic. There is focal disruption of the internal elastic lamina and there is concentric intimal fibroelastic thickening. The appearance is typical of chronic allograft vasculopathy. (Elastic van Gieson)

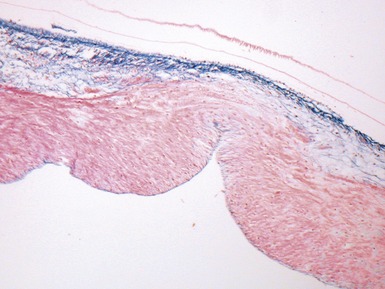

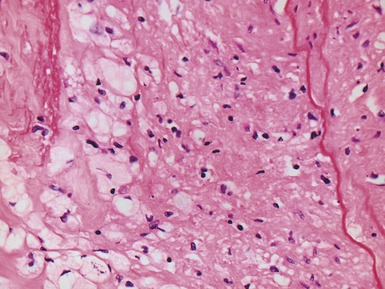

Fig 13.53 Same vessel as in Figs 13.51 and 13.52. Photomicrograph showing chronic allograft vasculopathy. A section through the vessel wall in which the adventitia is to the left and the intima to the right. There is fibrous replacement of much of the medial smooth muscle with a focal lymphocytic infiltrate. There is intimal fibrous thickening. There is an infiltrate of foam cells throughout the wall. This is in contrast to atherosclerosis where the foam cells are largely confined to the intima.

THE POST-TRANSPLANT ENDOMYOCARDIAL BIOPSY

CLINICAL FEATURES

ALLOGRAFT REJECTION AND GRAFT DYSFUNCTION (ACUTE AND CHRONIC)

Introduction

Table 13.3 ISHLT 2004 Standardized cardiac biopsy grading: Acute cellular rejection

| Grade 0 | No lymphocytic or macrophage infiltrate or myocyte damage. |

| Grade 1R: mild |

Perivascular and/or interstitial lymphocytic/histiocytic infiltrate that does not encroach on myocytes and does not distort the normal architecture; a single focus of myocyte damage is permitted |

| Grade 2R: moderate |

severe

The presence or absence of acute antibody-mediated rejection may be recorded as AMR 1 or AMR 0 respectively, as required

Specific issues of specimen handling

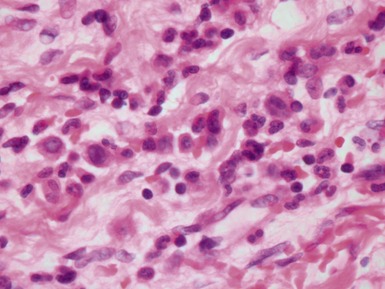

ACUTE CELLULAR REJECTION (Figs 13.54–13.56)

Differential diagnoses and pitfalls

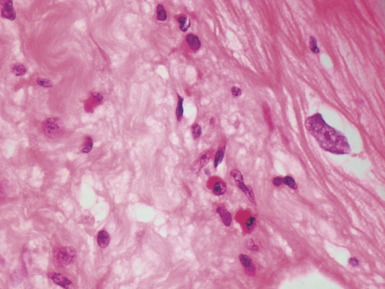

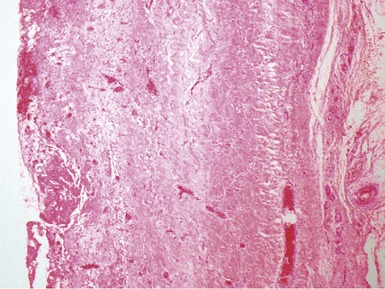

Early (perioperative) ischemic injury (Fig 13.57)

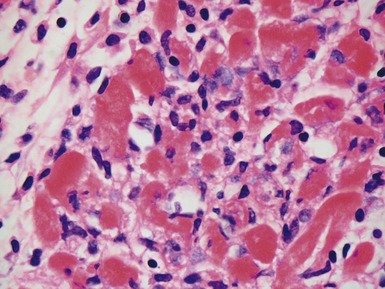

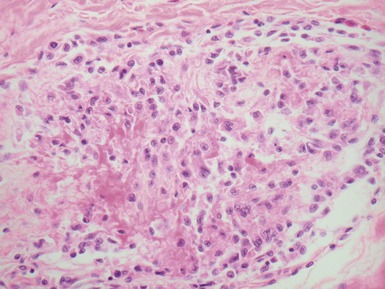

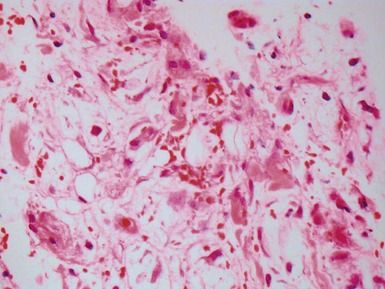

Fig 13.57 Photomicrograph of an endomyocardial biopsy showing ischemic change. The tissue has a ‘ragged’ look. The myocytes are shrunken and many have disappeared. There are hemosiderin containing macrophages with some recent hemorrhage. There is no significant inflammatory cell infiltrate. The biopsy was taken two weeks post-transplant.

ANTIBODY MEDIATED REJECTION

Introduction

POST-TRANSPLANT LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDER

POST-TRANSPLANT INFECTION

PATHOLOGY OF VALVES AND OTHER CARDIAC SPECIMENS

NORMAL VALVE STRUCTURE

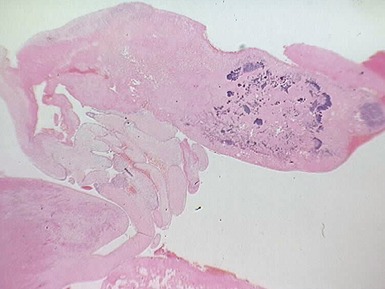

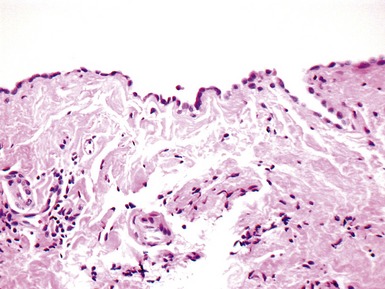

VALVE REGURGITATION

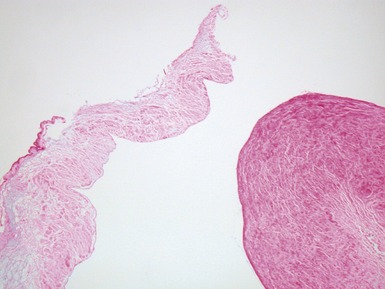

Fig 13.68 Photomicrograph of one of the valve leaflets from the case in Fig 13.67. The attachment site is to the left of the picture and the free edge to the right. The distal part of the leaflet shows mild fibrous thickening. The tip shows nodular thickening caused by laminar deposition of fibrous and elastic tissue. This tadpole profile is typical of valvar regurgitation. (Elastic van Gieson)

VALVE WITH ENDOCARDITIS

AORTIC COARCTATION

Clinical features

FIBROMUSCULAR DYSPLASIA

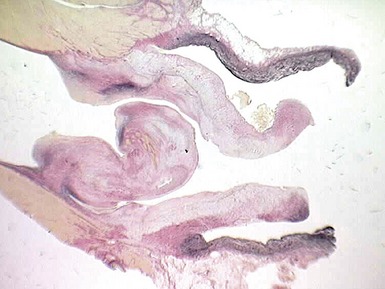

MARFAN’S SYNDROME

Histopathological features

Fig 13.77 Photomicrograph of the valve from Fig 13.76. The valve fibrosa is visible toward the upper part of the photo. The spongiosa shows some myxoid thickening and the atrial aspect shows laminar accretions of fibrous and elastic tissue. (Elastic van Gieson)

CARDIAC TUMORS

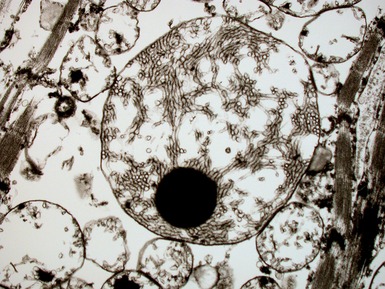

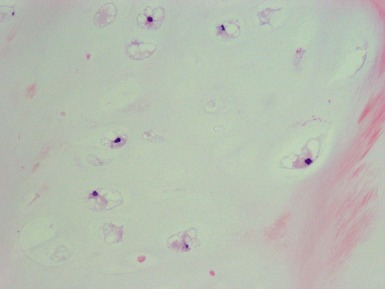

CARDIAC RHABDOMYOMA

CALCIFIED AMORPHOUS CARDIAC TUMOR

CARDIAC INFLAMMATORY MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMOR

PERICARDIUM

ACUTE PURULENT PERICARDITIS

Acebo E, Val-Bernal JF, Gomez-Roman JJ. Prichard’s structures of the oval fossa are not histogenetically related to cardiac myxoma. Histopathol. 2001;39:529-535.

Arad M, Maron BJ, Gorham JM, et al. Glycogen storage diseases presenting as cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:362-372.

Asimaki A, Syrris P, Wichter T, Matthias P, Saffitz JE, McKenna WJ. A novel dominant mutation in plakoglobin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:964-973.

Das BB, Recto M, Johnsrude C, et al. Cardiac transplantation for pediatric giant cell myocarditis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:474-478.

Gehrmann J, Sohlbach K, Linnebank M, et al. Cardiomyopathy in congenital disorders of glycosylation. Cardiol Young. 2003;13:345-351.

Laufs H, Nigrovic PA, Schneider LC, et al. Giant cell myocarditis in a 12-year-old girl with common variable immunodeficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:92-96.

Reynolds C, Tazelaar HD, Edwards WD. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:601-606.

Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow A, et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology task force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93:841-842.

Sebire NJ, Ramsay AD, Malone M, et al. Massive cardiac chondroma presenting with heart failure and superior vena cava obstruction in a teenage boy. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2004;23:325-331.

Sen-Chowdry S, McKenna WJ. Left ventricular noncompaction and cardiomyopathy: cause, contributor or epiphenomenon. Cur Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:171-175.

Schubert S, Abdul-Khaliq H, Lehmkuhl HB, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric heart transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13(1):54-62.

Tani LY, Veasy LG, Minich LL, Shaddy RE. Rheumatic fever in children younger than 5 years: is the presentation different? Pediatrics. 2003;112:1065-1068.

ter Heide H, Strander-Stumpel CT, Pals G, et al. Neonatal Marfan syndrome: clinical report and review of the literature. Clin Dysmorphol. 2005;14:81-84.

Webber SA, Naftel DC, Fricker FJ, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders after pediatric heart transplantation: a multi-institutional study. Lancet. 2006;367:233-239.

Yang Z, Bowles NE, Scherer SE, et al. Desmosomal dysfunction due to mutations in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2006;99:646-655.