Chapter 10 Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Introduction

Estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) show that cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounted for approximately 17 million deaths in 2001, this being approximately 30% of the total 57 million deaths due to chronic diseases.1 As of the mid-1990s, CVD is also the leading cause of death in developing countries. In Australia, for instance, CVD represented 34% of deaths registered in 2006.2 The leading underlying cause of death for all Australians was ischaemic heart diseases, contributing to 18% of all male deaths and 17% for all female deaths registered.

In fact, a global CVD epidemic has been predicted based on the epidemiologic transition in which control of infectious, parasitic, and nutritional diseases allows most of the population to reach the ages in which CVD manifests itself. Moreover, diet and lifestyle changes contribute to an increase in over weight and obesity and in the incidence of type 2 diabetes in Western countries, both of which are risk factors for CVD.1 CVD is currently the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the world.3

Reducing risk factors

For treatment and prevention of hyperlipidaemia see Chapter 18.

For treatment and prevention of hypertension see Chapter 19.

Obesity

A distinct relationship between body weight, blood pressure and CVD have been well documented, and the relative risk of developing hypertension, a risk factor for CVD, increases as body mass index (BMI) increases.4 Modest weight loss of approximately 10% of body weight can normalise blood pressure. A recent review of the Trials Of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP) phase II revealed that a weight loss of approximately 5 kg can result in a significant reduction in blood pressure.5 Advice about weight loss is essential. Maintaining weight loss is the greatest difficulty faced by patients. A healthy diet and regular exercise are essential for maintaining ideal BMI.

Recently it has been reported that people lose weight by just eating fewer calories, regardless of where those calories come from.6, 7 In this US study it was reported that after 2 years, 811 overweight adults randomised to 1 of 4 heart-healthy diets, each emphasising different levels of fat, protein, and carbohydrates, showed similar degrees of weight loss. On average, participants in the study lost 6 kg in 6 months, but gradually began to regain weight after 12 months, regardless of diet group. Briefly, the diets tested in the study included the same types of foods, but in different proportions, and were tailored to patients such that overall calorie consumption was reduced by approximately 750 calories per day, with each diet including a different macronutrient composition:

Prevention

The public and health professionals must implement comprehensive preventative programs that address lifestyle and nutritional issues if it is to achieve a significant reversal of the increasing incidence of CVD worldwide.1 The major focus is currently on treatment of CVD, however, there is increasing interest in dealing with the factors responsible for this disease, but more needs to be done. More is known about the factors responsible for CVD than most other diseases and hence it lends itself well to interventions with primary and secondary prevention.

The Australian Heart Foundation website provides extensive public and health professional information on risk factors, prevention and lifestyle strategies for hypertension and CVD.8

Lifestyle

Many studies consistently demonstrate greater reduction of cardiac risk factors by implementing positive lifestyle behavioural changes such as avoiding smoking, stress management, dietary changes, and physical activity.9, 10

Combining a low-risk diet and healthy lifestyle behaviour, such as moderate amounts of alcohol, being physically active, not smoking, and maintaining a healthy weight, can significantly reduce the risk of myocardial infarction according to a population-based prospective study of 24 444 post-menopausal women diagnosed with cancer, CVD and diabetes mellitus.11 Specifically the protective lifestyle factors included: not smoking, waist-hip ratio less than the 75th percentile (< 0.85), being physically active (at least 40 minutes of daily walking or bicycling and 1 hour of weekly exercise) and a dietary pattern characterised by a high intake of vegetables, fruit, wholegrains, fish, and legumes, in combination with moderate alcohol consumption (no more than 5 g of alcohol per day; a standard glass of wine contains 11g of alcohol). The authors concluded that most myocardial infarctions are preventable through lifestyle changes.

The Ornish program has shown that it is possible to reverse CVD in selected patients using a program that incorporates aspects to do with the causes of this disease, namely, psychological factors, nutritional factors and exercise.12 The Ornish program includes a very low fat, whole food, vegetarian diet rich in complex carbohydrates and low in simple sugars (supplemented with vitamin B12) along with regular walking, smoking cessation and stress management techniques. This program produced a 91% reduction in the frequency of angina and there was regression of coronary atherosclerosis after only 1 year and even more regression after 5 years in select patients.3 The control group had increased coronary atherosclerosis and increased angina after 1 year and even more stenosis after 5 years. This program has been criticised because patients can have difficulty in maintaining such a low-fat diet, plus tended to have increased serum triglycerides and decreased high density lipoprotein (HDL). Dietary fish or fish oil supplementation can be used to normalise triglycerides and have been demonstrated to improve survival in patients with coronary artery disease and hypercholoesterolaemia.13, 14

Despite an increasing interest by various public health authorities to recommend lifestyle and dietary changes to population groups, the general health of those groups is deteriorating as reflected by a decrease in physical activity and a massive increase in the problem of overweight and obesity.2

In recent reviews it has been shown that people in developed countries just do not consume the recommended daily allowance of 6–8 helpings of fruit and vegetables.15, 16 Hence the recommendations have included supplementation with good multivitamin and mineral preparations.5 In an article in the Heart Lung journal, Lewis encourages doctors to utilise nutritional supplements to assist in the management of patients with CVD.17 In his article he cites the benefits that are to be gained from patients adopting lifestyle–nutritional changes that can easily be annexed to traditional treatment options, and explains why it is necessary. A unique part of this article is how he describes the 3 distinct morphological processes of CVD and explains the difference between primary and secondary prevention. The 3 distinct pathological processes are plaque growth, which begins in adolescence and involves oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, plaque rupture, and clot formation which leads to immediate coronary artery occlusion and arrhythmias which result from myocardial ischemia. Understanding the timing of the distinct pathological processes allows for the most appropriate use of certain nutritional supplements.

Family lifestyle intervention for children

Obesity in children and adolescence is a growing problem in virtually every developed country and the prevalence is rising. Extrapolation from current US data found adolescent overweight is projected to increase the prevalence of obesity in adulthood (35-year-olds) in 2020 to 30–37% in men and 34–44% in women, which will consequently increase the incidence and risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), cardiac events and deaths in young adults and the middle aged.18 Management of the child to lose weight needs to focus on lifestyle interventions such as modifying diet, physical activity and behavioural therapies within the whole family. A recent Cochrane review evaluated the efficacy of lifestyle, drug, and surgical interventions to treat obesity in childhood.19 A total of 12 studies were directed at lifestyle interventions (physical activity and sedentary behaviour), 6 studies addressed diet and 36 evaluated behaviourally oriented treatment programs. This review concluded that family-based lifestyle interventions that modify diet and physical activity and include behavioural therapy can significantly help obese children lose weight and maintain that loss for at least 6 months compared to standard care or self-help alone.

Breast-feeding

A recent study investigated the relationship between duration of lactation and maternal incident myocardial infarction.20 It was reported that compared with parous women who had never breastfed, women who had breastfed for a lifetime total of 2 years or longer had 37% lower risk of CHD, adjusting for age, parity, and stillbirth history.

Mind–body medicine

Participants of a large prospective population-based cohort study of 6025 adults without CHD followed for a mean of 15 years demonstrated a dose-response relationship between emotional vitality (defined as a positive state associated with feelings of enthusiasm, energy, and interest) and reduced risk of CHD.21 The authors concluded: emotional vitality may protect against risk of CHD in men and women.

Depression and social isolation

Depression and social isolation are strongly associated with CVD and can have a major influence on prognosis.22 The impact of depression and social isolation is of a similar order to conventional risk factors such as smoking. A study of up to 500 patients hospitalised for acute coronary syndrome found that the onset of depression immediately following an acute cardiac event significantly influenced the long-term survival and illness severity of the patient.23

The Heart and Soul Study is a prospective cohort study of 1017 outpatients with stable CHD followed for an average period of 4.8 years.24 After adjustment for co-morbid conditions and disease severity, depressive symptoms were associated with a significant 31% higher rate of cardiovascular events compared with those with no depression, which was largely explained by negative behaviour patterns such as physical inactivity.

Worrying and mental stress are also a risk factor for cardiac events, CHD and accelerates atherosclerosis according to studies.25, 26

A cohort of 13 000 women and men demonstrated a doubling of the coronary risk factor with social deprivation over a 10-year period.27 Having a close friend for regular support when needed can reduce the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction by 50%.28

An expert working group for the National Heart Foundation of Australia did a systematic review of the literature and found strong and consistent evidence to indicate depression, social isolation and lack of quality social support is associated with the causes and prognosis of CHD.29

Owning a pet may help pet owners survive longer after a heart attack and reduces heart rate variability according to a US study of 100 patients following a myocardial infarction when compared with non-pet owners.30

Social support

The Framingham Heart Study social network followed up 4739 individuals over a 10-year period and found that people’s degree of happiness was determined by the happiness of others whom they are connected with, being surrounded by happy people and geographical proximity in close range.31 For example, a happy friend who lives within 1.6 km increases the probability that a person is happy by 25%. Similar effects were seen with partners, siblings who live close and next door neighbours, but not seen between co-workers. Effects are not seen between co-workers and happiness declined with time and geographical separation.

Unhappy marriage

An interesting 5-year follow-up study found that women with CHD had a 3-times higher chance of major cardiac events and death over the 5 years if they had a stressful marital or cohabiting relationship.32 Negative relationships can increase the likelihood of cardiac events and in 1 study this risk was estimated to be as high as 34% compared with low level negativity.33, 34 A good marriage also improved survival in women with heart failure.35

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and counselling

As emotional problems such as depression and anxiety can contribute to increased risk of heart disease, it would appear CBT and counselling play an important role in the management of patients with heart disease and/or psychological symptoms to help reduce risk factors.36

Stress

Stress has been identified as a causative factor in hypertension.37 Stress is also known to precipitate cardiac events and is considered a more important marker of myocardial infarction than hypertension and diabetes. For example, viewing a stressful soccer match doubles the risk of an acute cardiovascular event such as risk of angina, myocardial infarction or arrhythmia.38 A sudden emotional shock such as the loss of a loved one can cause symptoms of myocardial infarction even in patients with no clinically significant coronary disease39, including in young people by triggering coronary vasospasm.40

A review of the literature has found stress impacts adversely on health and on longevity and can increase the risk of stroke.41, 42 A study found that for women who are content with their lives at home and at work, atherosclerosis can actually regress, but progresses in those experiencing ongoing stress, independent of other CVD risk factors such as age, smoking, hypertension and HDL levels at baseline.43 A Lancet review found a strong and consistent association between stress and CVD.44

Work stress

A prospective cohort of almost 1000 middle-aged patients following a myocardial infarction demonstrated chronic work stress was associated with a twofold increased risk of CVD 2–6 years after returning to work compared with low job stress.45 In another study of London civil servants, being in a ‘just’ or fair workplace reduced the risk of CHD by 35% compared to employees who described their work as being ‘unjust’.46 Also, a sense of ‘lack of control’ at work can increase the risk of CHD.47

Hostility/anger

Hostility is now also recognised as a risk factor for CHD, raised blood pressure and heart rate and can increase risk of death by up to fivefold in men with a history of heart disease.48 Anger can also increase risk of CHD equivalent to hypertension as a risk factor.49 Anger management should be offered to patients who display hostile behaviour.

Managing anger also helps prevent atrial fibrillation (AF) according to a study of 4000 people aged 18–77 years involved in the Framingham Heart Study. The risk of AF was up to 30% higher in the people with very high hostility scores compared with low hostility.50

A number of mind–body approaches including biofeedback, meditation, yoga and hypnosis have all been shown to have a modest effect on lowering blood pressure.11

Transcendental meditation and stress management

A controlled trial of 138 hypertensive African American men and women (aged >20 years) assessed over a 6 to 9 month period, were randomised to a transcendental meditation group or control group and were monitored for carotid wall thickness to assess atherosclerosis.51 The transcendental meditation group showed a significant reduction in carotid atherosclerosis compared with an increase in the control group.

Heart disease patients who were taught stress management significantly reduced their risk of a repeat cardiac event by 25% compared with those receiving routine care.52

Music

A small study of 24 people, half of whom were musicians, found that faster music and more complex rhythms accelerated breathing and heart rate, whilst slower and more meditative music, especially reggae music, reduced breathing rates and heart rate. The researchers concluded that appropriate music can be cardio-protective by inducing relaxation, particularly during a pause.53 The pause reduced the heart rate, blood pressure, and minute ventilation below baseline.

Sleep

Siesta (afternoon nap)

Greek researchers demonstrated a daily siesta is protective towards CVD and coronary mortality according to a large scale cohort study of 23 681 individuals.54 After excluding confounders, occasional napping reduced risk of coronary mortality by 12%, and systematic napping by up to 37%, particularly in working men, compared with non-nappers. However, a recent report warns that excessive daytime sleepiness is an independent risk factor for total and cardiovascular-related mortality in elderly individuals.55

Sleep deprivation

Lack of sleep is being identified as a new risk factor for coronary artery disease, including calcification of the arteries. A US study of 500 healthy middle-aged men and women found that just 1 hour of extra sleep per night reduced the risk of calcification of the arteries (coronary artery calcification was measured by computed tomography) by an average of 33%.56 This association was more pronounced in women. The study adjusted for all other risk factors such as age, sex and BMI. The researchers postulated that blood pressure drops during sleep, so insufficient or poor quality sleep may interfere with the decline in blood pressure, increasing the risk of CVD.

A Japanese study of hypertensive patients also found after adjusting for confounders, short sleep duration significantly increases the risk of CVD compared with normal sleep duration.57 The researchers’ conclude that lack of sleep is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events.

Snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

OSA is a well-recognised risk factor for CVD and mortality, including nocturnal sudden cardiac death.58, 59 Sleep units are now well established in a number of hospitals, especially in developed countries, to help identify this problem and provide nocturnal oxygen inhalation therapy for those with confirmed sleep apnoea. Researchers found that sudden cardiac death occurred overnight significantly more in subjects with severe OSA (46%) than those without OSA (21%) or compared with sudden cardiac death victims in the general population (16%).60 An observational cohort study of 110 subjects who underwent bilateral carotid and femoral artery ultrasounds to quantify atherosclerosis, demonstrated snoring is a significant independent risk factor for carotid (not femoral) artery atherosclerosis; the risk factor increasing with degree of severity of snoring.61

Sunshine and vitamin D

Sunshine exposure, specifically solar ultraviolet B, is the major source for vitamin D production by the human body. Epidemiological studies indicate lack of ultraviolet light exposure may contribute to geographic and racial blood pressure differences, CVD and CVD mortality. 62–66 Deaths due to CVD are more common in the winter and at higher or lower latitudes.67 Vitamin D deficiency is common worldwide and epidemiological evidence is associated with increased risk of CVD, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, heart disease, congestive heart failure, myopathy, chronic vascular inflammation, peripheral artery disease, hyperparathyroidism, autoimmune diseases, diabetes, cancer and all-cause mortality as well as many other diseases (see also Chapter 30, osteoporosis).68–76 The proposed mechanisms include an increase in parathyroid hormone and activation of the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The hormone 1,25 hydroxy-vitamin D is involved in the production of renin which regulates blood pressure.

In a large prospective study the researchers demonstrated that deficiency in either 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D were equally associated with increase in all-cause mortality and CVD mortality.77 Serum parathyroid (PTH) levels increase when vitamin D levels fall below 75mmol/L. Slightly enhanced PTH levels are associated with CVD morbidity and mortality, as seen in renal patients and peripheral artery disease.78–80

Also, studies demonstrate vitamin D deficiency is linked with elevated C-reactive protein levels which are associated with increased cardiovascular events.81 Whilst an observation study did not demonstrate an association of CVD and low levels of 1,25 hydroxy-vitamin D in patients with myocardial infarction,82 community-based studies have shown a strongly positive correlation with low vitamin D contributing to the pathogenesis of congestive cardiac failure and myocardial infarction.83, 84 A recent study of over 3200 patients referred for coronary angiogram and assessed over an 8-year period, found a strong independent correlation with low serum 25(OH)vitamin D (7.6–13.3ng/ml) and double risk of cardiovascular mortality.85 Overall the weight of evidence points strongly towards an association of CVD and lack of sunshine and vitamin D deficiency. Due to its widespread benefit in many areas of health, safe sunshine exposure of at least 30 minutes daily, with walking, would appear to be of great benefit to anyone to ensure normal vitamin D levels and for the prevention and management of CVD.

Environment

Chemicals

Air pollution

Many studies consistently demonstrate an association between air pollution and CHD.86

The Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study analysing up to 66 000 participants over a 6-year period who were free of CVD at baseline, found each 10mcg/cubic metre rise in air particulate matter (<2.5mcg in diameter) of air pollution led to significant increased risks for cardiovascular events and death linked to CHD, stroke and death from stroke.87, 88 These findings strengthen previous studies focusing on city areas linking CVD and air pollution.89, 90

Exposure to particulate air pollution also increases the risk of Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), estimated by up to 70% in a high polluted area compared with a control group and more pronounced in men than in women.91

Diesel and/or carbon emissions

significantly more profound during exposure to polluted air than in the control group who used clean air, and also reduced the acute release of endothelial tissue plasminogen activator, thereby increasing the thrombotic effect.92 These factors may explain the mechanism for increased CVD risk with combustion-derived air pollution.

Smoking

Smoking can reduce all-cause mortality after smokers quit smoking. The Nurses Health Study, a prospective observational study of nearly 105 000 women over a 20-year period, found significant reduction in all-cause mortality in the first 5 years of smoking cessation by 13% and returned to the same level as non-smokers at 20 years compared with those who continued smoking during these periods.93 Risk of death from vascular disease declined to non-smoking levels in 20 years. Smoking cessation can substantially improve health outcome, reduce CVD and reduce health care costs.94

Physical activity

Exercise

A sedentary lifestyle may increase the risk for depression, hypertension, excess weight, abnormal lipids and CVD. It is well established that regular exercise for 30 minutes on most days can help prevent hypertension.95 Exercise of this magnitude is important in maintaining an ideal weight and helping to normalise abnormal lipids.

A 15-year, prospective longitudinal study of up to 5000 men and women (aged 18–30 years), found walking throughout adulthood attenuates the long-term weight gain that occurs in most adults.96

The National Heart Foundation and Medical Journal of Australia guidelines for clinically stable CVD recommend 30 minutes of low-moderate exercise most days which helps to reduce cardiovascular symptoms, augment physiological functioning, improve coronary risk profile and improve muscular fitness.97 They also recommend for those who have suffered a recent cardiovascular event to have supervised exercise rehabilitation.

A study reporting on non-pharmacologic treatments for depression in patients with CHD reported that of the psychological therapies, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT), aerobic exercise, St John’s wort, essential fatty acids, S–Adenosylmethionine (SAMe), acupuncture, and chromium picolinate, it was aerobic exercise that offered more promise to improve both mental and physical health due to its effect on cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes, however, future trials are warranted.98

Yoga

Yoga has been recommended as efficacious in the primary and secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease and post-myocardial infarction patient rehabilitation.99 There are several studies that demonstrate yoga can reduce cardiovascular reactivity to stress, a factor that is strongly associated with cardiovascular risk.100 Controlled studies have demonstrated that yoga can reduce blood pressure (see also Chapter 19, hypertension) and hence cardiovascular risk.101–105

Tai chi

Tai chi promotes balance and flexibility, and can improve cardiovascular fitness and have substantial emotional benefits according to a control study.106, 107

Qigong

Several randomised controlled trials have evaluated qigong interventions from multiple perspectives, specifically targeting older adults.101 In adults, particularly the aged, this form of physical activity can lead to significant improvements in physical functioning, mood, weight, and in the reduction of cardiovascular risk factors.101 Improvements in cardiovascular factors such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure, increased pre-ejection fraction and heart rate variability have been documented.108–111

Physical therapies

Musculoskeletal therapy

Some complementary and alternative physical therapies show promise in cardiac rehabilitation.112 A recent study with stroke patients reported that single-modality exercises targeted at existing impairments do not optimally address the functional deficits of walking but did ameliorate the underlying impairments.113 Also the study reported that the underlying cardiovascular and musculoskeletal impairments were significantly modifiable years after stroke with targeted robust exercise. In another recent study it was reported that regular arm aerobic exercise lead to a marked reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressures and an improvement in small artery compliance.114 The study further concluded that arm-cycling was a logical option for hypertensive patients who choose to support blood pressure control by sports despite having coxarthrosis, gonarthrosis, or intermittent claudication.

Acupuncture

An early report concluded that there were sufficient clinical studies in humans that demonstrate acupuncture can exert significant effects on the cardiovascular system and provide effective therapy for a variety of cardiovascular ailments.115 In a recent study of acupuncture and cardiac arrhythmias; the 8 eligible studies reviewed demonstrated that 87–100% of participants converted to normal sinus rhythm after acupuncture. Hence it was concluded that acupuncture seemed to be effective in treating several cardiac arrhythmias, but limited methodological quality of the studies necessitates better-controlled clinical trials to be performed.116

Nutritional influences

Diet

Dietary regimens that increase obesity and raise blood lipid levels and inflammatory markers (i.e. C–reactive protein) have an important role in increasing the risk for the development of chronic diseases such as myocardial infarction and stroke. It has been recently reported that vegetarians have a decreased prevalence of ischemic heart disease mortality that is probably due to lower total serum cholesterol levels, lower prevalence of obesity and higher consumption of antioxidant-type compounds in foods.117

Worldwide dietary patterns

Diet is a modifiable risk factor for CVD. The INTERHEART study involving 52 countries identified 3 major dietary patterns: Oriental (high intake of tofu, soy and other sauces), Western (high in fried foods, salty snacks, eggs, and meat), and prudent (high in fruit and vegetables).118 The study demonstrated an inverse association between the prudent pattern and acute myocardial infarction (AMI); the Western pattern showed a U–shaped association with AMI; the Oriental pattern demonstrated no relationship with AMI. The researchers concluded that the unhealthy dietary intake increases the risk of AMI globally and accounts for about 30% of the population-attributable risk.

The INTERGENE population study of 3452 participants (aged 25–74 years) identified dietary patterns associated with CVD risk factors, obesity and metabolic syndrome.119 Unhealthy food patterns were characterised by high consumption of energy-dense drinks and white bread, and low consumption of fruit and vegetables. Healthy food patterns was distinguished by more frequent consumption of high-fibre and low–fat foods and lower consumption of products rich in fat and sugar.

A recent Cochrane review of the literature also demonstrates dietary advice lowers prevalence and incidence of CVD.120

The Seven Countries study demonstrated that population-related factors significantly affect the risk of CVD and that diet was directly related to the risk of developing coronary artery thrombosis that lead to heart attacks.120 Dietary factors were far more significant than other risk factors, as variations in cholesterol and incidence of smoking in men from one country to another did not account for the differences seen in CVD. This study also demonstrated lower levels of many cancers, dementia and all-cause mortality in people who adhered closely to their traditional Mediterranean or Japanese diets.

Obesity

Weight management can significantly reduce cholesterol and other known risk factors, and slow progression of coronary artery disease that is associated with calcium deposition as with atherosclerotic plaque disease and coronary events in a cohort of patients with type 1 diabetes.122

Mediterranean and Japanese diets

Vast quantities of research, including epidemiological studies, have demonstrated the value of the Mediterranean and Japanese diet in the prevention and management of CVD. Their dietary patterns feature high intakes of seafood, vegetables, nuts (e.g. walnuts) and seeds, cereals, fruit (usually for dessert) and legumes. The Mediterranean diet is also rich in olive oil intake. Both diets have some chicken, are low in red meat and dairy, and are mostly vegetarian and high in fish. The saturated fat content of egg and dairy products in the Mediterranean and Japanese diets (e.g. goats or sheep products such as yoghurt and cheeses, which forage on wild greens) differs from Western dairy intake in that they have higher content levels of omega-3 fatty acid (alpha linolenic acid).123

Interestingly, a recent Japanese study found that high intake for fruit and vegetables was protective for CVD in women but not men.124 High dietary soy may be cardio-protective according to a study of post–menopausal women by reducing blood pressure and lowering lipid levels.125

A recent study that investigated the Mediterranean diet and the incidence of mortality from CHD and stroke in women reported that a greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet, as reflected by a higher alternate Mediterranean diet score, was associated with a lower risk of incident CHD and stroke in women.126

Olive oil

A study of patients with stable CHD aimed to identify the effects of olive oil on cardiac risk factor blood parameters.127 The placebo-controlled, cross-over, trial randomised patients with either raw daily dose of 50ml of virgin olive oil or refined olive oil over a total 6-week period and found reduction in the inflammatory markers interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein with virgin olive oil intervention compared with refined olive oil group, but no changes observed with glucose and lipid profile.

The polymeal

The polymeal, as opposed to the polypill, are the foods identified to be cardio-protective. The polymeal is far safer and more natural and can reduce the risk of CVD by more than 75% (see Table 10.1).128 Taking the polymeal daily significantly increased total life expectancy far greater in men than in women.

Table 10.1 Effect of ingredients of polymeal in reducing risk of CVD

| Ingredients | Average percentage reduction (95% CI) in risk of CVD source | NHMRC level of evidenceMA = meta-analysis; RCT = randomised controlled trial |

|---|---|---|

| Wine (150ml/day) | 32 % | MA |

| Fish (114g x 4 times/week) | 14% | MA |

| Dark chocolate (100g/day) | 21% | RCT |

| Fruit and vegetables (400g/day) | 21% | RCT |

| Garlic (2.7g/day) | 25% | MA |

| Almonds (68g/day) | 12.5% | RCTs |

| Combined effect | 76% (63 to 84%) |

(Source: adapted from Franco et al. 2005)128

A recent meta-analysis of 12 prospective cohort studies of over 1.5 million participants over a 3–18 year period affirms the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet.129 Stricter adherence to the diet conferred significant cardiac protection, and led to further reductions in risk of all cause-mortality, death from CVD, as well as cancer and degenerative diseases compared with low adherence. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet can also significantly reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes.130

The dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet

The DASH trial, which was an 11-week multi-centre feeding trial, tested the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. Participants (459) were divided into 3 groups; control, increased fruit and vegetables and a combination diet (rich in fruits, vegetable, low fat dairy and reduced saturated fat). In hypertensive subjects, the combination diet led to a mean reduction of blood pressure of –11.4 mmHg systolic and –5.5mmHg diastolic.131 It was also found to lower homocysteine.132

Furthermore, the DASH diet also reduces the risk of heart disease and stroke among women independent of lowering hypertension.133 An analysis of the Women’s Health Study involving over 88 000 women demonstrated adherence to the DASH diet significantly reduced the incidence of cardiac mortality or myocardial infarction by 24% and reduced the risk of stroke by 18% compared with a diet high in salt or fat during 24 years follow-up. It also reduced plasma levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin, both inflammatory markers.

High fibre diet

Total dietary fibre (cereal, fruit, and vegetable) is associated with a 14% reduction in the risk of all coronary events and a 27% decrease in the risk of coronary death.134 Further research confirms its protective role towards CVD according to analysis of the Physicians Health Study I, that demonstrated consumption of wholegrain cereal at breakfast and high dietary fibre are associated with less prevalence of hypertension, lower risk of heart failure and reduced incidence of myocardial infarction.135 Intakes of wholegrain fibre are inversely associated with progression of atherosclerosis, according to a study on post-menopausal women with coronary artery disease.136 Oatmeal for breakfast also reduces the risk of CHD.137

Low-fat diet

In the Mediterranean diet, Cardiovascular Risks and Gene Polymorphisms (Medi-RIVAGE) study from France, both the Mediterranean-type diet and the low-fat diet significantly reduced the risk factors for CVD equally for total cholesterol, triglycerides and insulinemia after adjustment for BMI during the 3-month intervention.138

Vegetarian diet

A vegetarian diet has been reviewed for its beneficial and adverse effects in various medical conditions.139 It was concluded in that study that the beneficial effects may be due to the diet (consisting of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, minerals, fibre, complex carbohydrates, antioxidant vitamins, flavanoids, folic acid and phytoestrogens) as well as the associated healthy lifestyle that vegetarians pursue. There were few adverse effects reported and these consisted of increased intestinal gas production and a small risk of vitamin B12 deficiency.

A more recent report conducted over a mean of 8.1 years suggested a dietary intervention that reduced total fat intake and increased intakes of vegetables, fruits and grains did not significantly reduce the risk of CHD, stroke, or CVD in post-menopausal women and achieved only modest effects on CVD risk factors, suggesting that more focused dietary and lifestyle interventions may be needed to improve risk factors and reduce CVD risk.140

Fish and omega–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

The benefits of eating just 1–2 servings of fish weekly can significantly reduce the risk of coronary death, which outweighs harm from contaminant exposure from mercury and dioxins from fish intake.141 Modest intake of fish consumption compared with eating fish only once weekly substantially reduced the risk of CHD amongst middle-aged persons.142 This prospective study of nearly 42 000 Japanese people demonstrated the more fish intake the lower the risk of CVD. The group with the highest fish intake, equivalent to 180g daily, reduced the CVD risk by 40%.

A number of cohort studies demonstrate that regular consumption of fish, even just 1–2 servings weekly, is associated with reduced risk of sudden death, cardiac arrest, heart failure and atrial fibrillation, compared with those who only eat fish once monthly.143, 144, 145

Nuts

It is well recognised that nut consumption (e.g. 30–65g or 6–13 walnuts), which are high in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and alpha-linolenic acid, is important for a healthy heart, improves vascular health and lowers lipid levels.146, 147 The Mediterranean diet usually consists of regular nut consumption. Of interest, pistachio nuts have a dose-response beneficial effect in reducing risk of CVD.148 Just 2 doses of pistachios added to a low-fat diet can significantly reduce cholesterol levels in a dose-dependent manner. Pistachios have a high amount of phytosterol which may be contributing to the health benefits as well as lowering cholesterol levels. Another study demonstrated that sunflower seeds may also have the same benefit on CVD due to high phytosterol levels also.149

Diet high in vitamin K

A diet high in vitamin K, particularly K2, is known to be protective for not only bones but also vascular health150, 151

The Dutch Rotterdam study of over 4800 participants with no history of heart attacks found that a high dietary vitamin K2 intake in the upper third was associated with a 57% lower risk of dying from fatal cardiac disease and 52% reduction in severe aortic calcification compared with those in the lower third of total vitamin K2 intake.152 Furthermore, all-cause mortality reduced by 26%.

Only 10% of dietary vitamin K intake is in the K2 form, the other 90% being the more common K1. Vitamin K2 is obtained mainly from the ‘good’ bacteria produced in the digestive tract and is also found in certain fermented foods. The ideal dietary source of K2 is natto, Japanese fermented soybeans.154 vitamin K2 dietary sources also include butter, eggs, cow liver, fermented products and hard white cheese.

Salt/sodium restriction

Data from 2 randomised trials, TOHP I and TOHP II, involved a total of 3126 participants assessed over a 10–15 year period who were randomised to a sodium reduction intervention or control for 18 months (TOHP I) or 36-48 months (TOHP II).155 The researchers found a significant reduction in risk of a cardiovascular event by up to 30% among those in the low-sodium diet intervention group compared with control group. The researchers concluded: ‘Sodium reduction, previously shown to lower blood pressure, may also reduce long-term risk of cardiovascular events’. 154

A low-salt diet is also cardio-protective in normotensive patients, as well as effectively lowering blood pressure in hypertensives. A recent study of normotensive overweight and obese adults were randomised to low or standard diet groups.155 Within 2 weeks the low-salt diet group (50nmol sodium per day) demonstrated 30% less brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation, lower systolic blood pressure and reduced 24 hour sodium excretion compared with the standard diet group. This study highlights the need to remove salt from many prepared foods and in the diet to prevent the onset of hypertension.

Cocoa and/or dark chocolate

Several studies have shown that cocoa can decrease blood pressure to a similar extent to that of pharmaceuticals.156 New research suggests 1 serving of dark chocolate (20g; not milk chocolate) every 3 days significantly reduces the levels of the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein which may help to reduce inflammation, a known risk factor for many diseases, including CVD and cancer.157 A 30-day trial demonstrated drinking a cup of cocoa daily can improve flow-mediated dilation and combat blood vessel dysfunction linked to diabetes.158 Daily consumption of 46g of dark chocolate increased blood levels of flavonoid epicatechin and significantly improved arterial function in a group of healthy volunteers.159

Alcohol

Whilst the cardio-protective properties of moderate alcohol consumption, compared with abstinence or heavy drinking, are widely recognised, this interesting study, a longitudinal-based cohort study, aimed to identify whether the benefits are experienced equally by all moderate drinkers.160 The study found a significant benefit of moderate drinking was identified amongst those with poor health behaviours (little exercise, poor diet and smokers) compared with abstinence or heavy drinking. There was no additional benefit from alcohol amongst those with the healthiest behaviour profile (>3 hours vigorous exercise per week, daily fruit or vegetable consumption and non-smokers). The authors concluded the cardio-protective benefit from moderate alcohol drinking ‘does not apply equally to all drinkers, and this variability should be emphasised in public health messages’.160 However, another large-scale US study of a cohort of 8867 men over 16 years found after adjusting for confounders, moderate levels of alcohol (5–30g per day) reduced the risk of myocardial infarction by up to 50%.161

Green and black tea

A large prospective cohort study involving 40 000 Japanese adults (aged 40–79 years) over an 11-year follow-up, after adjusting for demographics, lifestyle and medical risk factors, found that green tea consumption was associated with significant reduction of all-cause and cardiac mortality, but not for cancer mortality. The inverse association was particularly in those drinking more than 5 cups of tea daily, compared with less than one, and was stronger in women than men.165

Similarly, drinking at least 3–4 cups of black tea a day was also protective for cardiac disease and reduced the risk of developing MI, according to a review of the literature.165

Coffee and energy caffeinated beverages

There is increasing consumption of energy caffeinated drinks by young people. A published case report described an otherwise healthy 28-year old man who developed a cardiac arrest due to an ischaemic event from vasoconstriction, even though angiogram did not show significant coronary lesions, and arrhythmia triggered by the excessive ingestion of caffeine- and taurine-containing energy drinks and strenuous activity.166 Caffeine before exercise might be more significant as it may impede blood flow during exercise. According to a study of young regular coffee drinkers, just 200mg caffeine dose (equivalent to 2 cups of coffee daily), significantly reduces exercise-induced myocardial flow reserve and this effect is more pronounced at high altitude.167

A large US study of over 125 000 adults found even drinking in excess of 6 cups of coffee (mostly filtered coffee) per day did not increase risk of CHD, even in those with type 2 diabetes or who were obese; however, they were more likely to take aspirin, possibly for caffeine withdrawal symptoms!168

A 3.5 year follow–up study of over 11 000 men who had had a myocardial infarction in the previous 3 months, demonstrated that moderate caffeine consumption (2–4 cups daily) did not increase cardiovascular events. 169

Pomegranate juice

An RCT demonstrated drinking daily pomegranate juice for 3 months compared with placebo can improve myocardial perfusion in patients with CHD and ischaemic disease.170 Pomegranate can also improve serum lipids.

Phytonutrient juice powder

A recent pilot study suggests that a phytonutrient concentrate consisting primarily of fruits, vegetables and berries — including acerola cherry, apple, beet, bilberry, blackberry, black currant, blueberry, broccoli, cabbage, carrot, cranberry, Concord grape, elderberry, kale, orange, papaya, parsley, peach, pineapple, raspberry, red currant, spinach and tomato — induced several favourable modifications of markers of vascular health in the study participants. The study supported the concept that plant nutrients are important components of a heart-healthy diet.171

Nutritional supplements

Antioxidants

A US cross-sectional study assessed users of a broad range of daily nutritional, herbal and dietary supplements.172 After adjustment for age, gender, income, education and BMI, supplement use was associated with optimal levels of chronic disease biomarkers (serum homocysteine, C-reactive protein) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides, less likely to have sub-optimal blood nutrient levels, elevated blood pressure, high BMI and diabetes compared with non-users or multivitamin/mineral users alone.

A trial of 13 017 French adults (7876 women aged 35–60 years and 5141 men aged 45–60 years) randomised to either a single daily capsule of antioxidants (120mg of ascorbic acid, 30mg of vitamin E, 6mg of beta-carotene, 100mcg of selenium and 20mg of zinc) or a placebo over a 7.5 year period. The study found the antioxidant supplement reduced the risk of cancer and all-cause mortality in men, but not in women.173 The researchers postulated that men are more likely to have lower baseline status of certain antioxidants, especially of beta-carotene.

Vitamins E and C

There is increasing biological plausibility for the use of vitamin supplements for the prevention of CVD. Oxidised LDL cholesterol attracts and interacts with monocytes, macrophages and platelets to promote atherogenesis and also causes endothelial necrosis plus interferes with vaso-relaxation. vitamins E and C have been shown to inhibit LDL oxidation and vitamin E reduces endothelial monocyte adhesion, as well as inhibiting platelet activation.174–176 Angiographic and ultrasonographic studies in humans suggest that vitamin E also inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis.8, 9, 177 Often researchers do not distinguish between the synthetic and natural forms of vitamin E which have different structures and functions. Studies in general that utilise natural vitamin E and at doses of 500IU or above have shown a benefit.178 Whereas, studies that employed a lower dose or the synthetic form of the vitamin were found to be ineffective.11 There is a known synergy between vitamin E and vitamin C plus selenium that allows for a maximum benefit.

Vitamin E is synergistic also with aspirin as they are both cyclooxygenase inhibitors which significantly increases the efficacy of aspirin therapy.179 Unfortunately, there are no primary prevention studies that have evaluated the role of natural vitamin E. Vitamin C, in addition to regenerating the antioxidant properties of vitamin E, has an anti-inflammatory action which is thought to be important in the prevention of arterial disease.180

According to the Physician’s Health Study II, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of high doses of synthetic vitamin E (400IU 2nd daily) with vitamin C (500mg daily), or provided alone, compared with placebo over an 8-year period was not cardio-protective and did not reduce total mortality.181 It was also concerning that the vitamin E treatment group had a marginally significant increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, which is plausible as vitamin E is known to prolong bleeding times. It is likely the benefits of vitamin E witnessed in other trials are found with the natural forms (not synthetic).

Findings from the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular study of 1450 women also demonstrated no overall benefit of either ascorbic acid (500mg/d), vitamin E (600IU every other day) and beta-carotene (50mg every other day) for CVD, although there was a marginally significant reduction in the vitamin E group in women with prior history of CVD and those randomised to both active ascorbic acid and vitamin E experienced fewer strokes.182 There are concerns with the use of synthetic vitamin E.

Vitamin B

Nicotinic acid (Niacin)

Niacin lowers LDL cholesterol as well as triglycerides plus raising HDL and lowering total cholesterol. The major drawback is that it causes flushing at high doses and can cause liver toxicity.183 A slowly released form of niacin is generally better tolerated. Further, a meta-analysis of niacin has shown that it is a safe and an effective option for dyslipidemia.184

Folate, vitamin B12, vitamin B6 and Homoceysteine

Previously only very high levels of homocystine were thought to be related to coronary artery disease. More recent data suggests that levels as low as 12mol/L may increase the risk of vascular disease.185 There is a relationship between homocysteine levels and vascular disease that is supported by epidemiological data. However, there are also negative studies. Homocysteine is an amino acid product of normal protein metabolism. Folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 are all involved in the metabolism of homocysteine. Deficiencies of 1 or more of these vitamins can lead to hyperhomocysteinemia.15, 186 Folic acid in combination with vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 have emerged as potentially valuable nutrients for the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis.16

Since the voluntary fortification of foods in Australia with folate, serum folate levels have risen and there has been a corresponding reduction of homocysteine levels in a group of 468 adults in Western Australia over a 4-year period.187

Moreover, it is of relevance that elevated homocysteine levels have also been linked with Alzheimer’s disease and hence normalisation of homocysteine levels through the use of folic acid may also provide protection from this disease.188 Further, folic acid has been shown to be extremely useful for the prevention of most congenital abnormalities,189, 190 as well as multiple cancer sites that include the cervix, large bowel and breast.18, 19, 191, 192, 193

However, there are mixed results for any cardiovascular benefit with folate and vitamin B12 supplementation even where homocysteine levels have dropped. For example, a large US study of 5442 women with CVD or with 3 or more risk factors for CVD was randomised to a daily combined pill of folate (2.5mg) and vitamins B6 (50mg) and B12 (1mg) or placebo.195 Whilst homocysteine serum levels significantly dropped by 18%, there was no reduction in deaths or cardiovascular events observed in the treatment group compared with placebo. A second large study of 3046 patients over an 8-year period, also demonstrated no preventative effect of intervention with folic acid with vitamin B6 or B12 despite significantly reducing homocysteine levels by 30% after 1 year supplementation with folic acid and vitamin B12.195 The study groups received daily oral treatment with folic acid (0.8mg) plus vitamin B12 (0.4mg) plus vitamin B6, (40mg) (n = 772); or folic acid plus vitamin B12 (n = 772); or vitamin B6 alone (n = 772); or placebo. These findings did not support the use of B vitamins as secondary prevention in patients with CAD. B group vitamins may be more appropriately indicated for primary prevention.

Vitamin D

Trials demonstrate vitamin D supplementation can help lower blood pressure through the production of the hormone renin which affects the renin-angiotensin system and has a direct effect on blood pressure.78, 196 Also studies demonstrate vitamin D supplementation can reduce elevated C-reactive protein levels which are associated with increased cardiovascular events.197

Consequently, there is a good rationale for supplemental vitamin D which is simple and safe for the prevention of vascular events in those with vitamin D deficiency and risk factors for or established CVD, such as the elderly and those institutionalised.198

Vitamin K

Low dose vitamin K (K1 and K2) supplementation may protect against atherosclerosis and heart disease, including in patients taking warfarin.199, 200

According to several animal studies, patients taking warfarin are susceptible to developing atherosclerosis from calcification of the arterial walls. vitamin K2, not K1, inhibits warfarin-induced arterial calcification in animal studies.201, 202 Very low dose vitamin K2 supplementation (50–70mcg/day) may help stabilise INR fluctuations in patients with vitamin K deficiency, although this needs great care under medical supervision and dietary sources are safer.203–207 vitamin K (oral or intravenous) is used to reduce excessively high INR in patients on warfarin.

Minerals

Magnesium

There has been increasing attention given to the role of magnesium and selenium in CVD. Magnesium deficiency has been shown to produce coronary artery spasm which is thought to be a cause of non-occlusive heart attacks.208 Furthermore, it has been observed that men who die suddenly of heart attacks have significantly lower levels of myocardial magnesium as well as potassium than matched controls.23

It has been suggested that magnesium should become the treatment of choice for angina that is due to coronary artery spasm. Magnesium has also been found to be helpful in the management of arrhythmias and in angina due to artherosclerosis.209 Oral magnesium therapy improves endothelial function, exercise tolerance, reduces exercise-induced chest pain and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease.210, 211 Magnesium is known to be an effective smooth muscle relaxant. It is likely it could even have benefit for angina in the acute setting.

The Paris Prospective Study 2, a cohort of 4035 men (age 30–60 years) during an 18-year follow-up based on baseline serum mineral levels, demonstrated low serum magnesium and high serum copper, and concomitance of low serum zinc with high serum copper or low serum magnesium, contributed significantly to an increased all-cause mortality, mortality cancer risk and cardiovascular deaths in middle-aged men.212

Magnesium also helps lower blood pressure which has a favourable effect on CVD (see Chapter 19, hypertension). There is a significant inverse relationship between serum magnesium and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.213 Meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrates it is effective for hypertension.214

Intravenous magnesium

Over the last 20 years there have been over 17 well-designed studies demonstrating that intravenous magnesium during the first hour of admission into hospital for an acute myocardial infarct (MI) can produce a favourable effect in reducing death rates.215 Magnesium infusion in 250 patients with suspected MI, resulted in a 54% reduction in mortality from cardiac disease compared with placebo.216 Its benefit in this situation relates to many properties including dilatation of the coronary arteries, reduction in peripheral vascular resistance, improving cardiac energy production, inhibiting platelet aggregation and probably most importantly improving heart rate and arrhythmia.217 Key factors in the use of intravenous magnesium are timing after onset of symptoms and timing in relation to thrombolysis, and giving the correct rate of magnesium infusion.218 Controversy surrounds the use of intravenous magnesium in acute myocardial infarction because the 2 large negative trials (ISIS-4 and MAGIC)219, 220 involving more than 64 000 patients, and therefore with stronger statistical power calculations, used a higher dose of intravenous magnesium in the first 24 hours than any of the prior positive studies. There has as yet been no published dose-related meta-analysis of intravenous magnesium in acute myocardial infarction.

Calcium

A large trial of 1471 healthy post-menopausal women (mean age 74), were randomised to either calcium supplementation alone or placebo over a 5-year period.221 Myocardial infarction, stroke and sudden death were significantly higher in the calcium group by over 50% compared with the placebo group. The researchers note the detrimental effect on CVD could outweigh any benefits on bone from calcium supplements. More studies are warranted to assess if calcium combined with magnesium and vitamin D, may offset these effects.

Selenium

Some epidemiological studies have shown an inverse relationship between the incidence of CVD and selenium intake.222 The possible anti-artherogenic activity of selenium may in part be due to its antioxidant activity.223

Selenium also decreases platelet aggregation by preventing lipoperoxide accumulation. Lipoperoxides impair prostaglandin synthesis and promote thromboxane synthesis which can increase platelet aggregation. The selenium content of foods is very much linked to its content in soil and it is very much dependant on the region where the food has been produced.224

It is of significance that low selenium levels have been found to be associated with several cancers such as prostate and bladder cancer and that selenium supplementation appears to be highly protective against cancer development.30, 225 (For more information see Chapter 9.)

Fish oils / omega-3 fats

Research including a meta-analysis of the literature, suggest taking just 1 capsule of fish oil supplements (1g daily) can lower resting heart rate, stabilise heart rate variability and reduce risk of fatal dysrhythmias which may explain its cardio-protective properties.226–229

United States recommendations

The American Heart Association recommends that fish oil be considered for all patients who have recovered from MI.230 Moreover, the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association has also recommended that fish oil needs to be considered in all patients following a heart attack due to its proven benefit for reducing sudden death.231

Further, recently the American Heart Foundation carried out an extensive review of the scientific literature regarding omega-6 fatty acids and risk for CVD.232 The advisory committee concluded that based on the current evidence, from aggregate data from randomised trials, case-control and cohort studies, and long-term animal feeding experiments indicate that the consumption of at least 5–10% of energy from omega-6 PUFAs significantly reduces the risk of CHD relative to lower intakes. The data also suggested that higher intakes appear to be safe and may be even more beneficial (as part of a low-saturated-fat, low-cholesterol diet regimen).

Australian recommendations

The Australian Heart Foundation has prepared an extensive review of the literature that includes meta-analyses on the value of omega-3 PUFAs and fish in the prevention of CVD that includes cardiac disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction and stroke.233 For established CVD in an adult, the Heart Foundation recommends fish oil supplementation be strengthened to include consumption of approximately 1g Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) plus Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and >2g Alpha Linolenic Acid (ALA) daily. Other studies recommend dosage of EPA and DHA in the combined range of 800–1000mg daily for both primary and secondary prevention of CVD.234 The authors have concerns about the recommendation of linseed in bread because of the potential for damage to linseed ALA with heat. (See Table 10.2.)

| To lower their risk of CHD, all adult Australians should: | Health professionals should advise adult Australians with documented CHD to: |

|---|---|

(Source: adapted from Australian Heart Foundation recommendations)233

Lipid profiles

Omega-3 fish oils have been shown to favourably affect lipid profiles, platelet aggregation and arrhythmia and may reduce plaque rupture and clot formation hence its potential for reducing cardiac events as well as reducing sudden death.235 Docosahexaenoic acid decreases vascular adhesion and eicosapentaenoic acid increases nitric oxide production.

Evidence from a clinical trial suggests that dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids using a dosage of 900mg per day over 3.5 years leads to a clinically important and statistically significant cardiovascular benefit.222

Furthermore, in diabetics a larger dose of 4g of omega-3 fatty acids daily improved endothelium function.236 It is highly recommended diabetics consider fish oil supplementation for the prevention of diabetic related CVD.

Other nutritional supplements

Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone)

CoQ10 is a vitamin-like nutrient. Its primary role relates to the production of energy (ATP) in the mitochondria and it also acts as an antioxidant. CoQ10 is known to have anti-hypertensive properties by normalising peripheral resistance (see Chapter 19, hypertension).

A large body of growing data supports the potential use of CoQ10 for mitochondrial diseases with heart involvement, heart failure and cardiomyopathy in both adults and children.237–240

The ENDOTACT study demonstrated a positive influence of CoQ10 supplementation on human endothelial function independent of lipid lowering .241 In a study of 38 patients with coronary artery disease, they were randomised to either oral CoQ10 (300mg daily divided into 3 doses) or placebo for 1 month.242 All patients were assessed for brachial artery endothelium-dependent assessment, cardiopulmonary exercise test, and the measurement of endothelium-bound ecSOD activity (baseline and post-study). All parameters, such as endothelium-dependent dilatation and improved peak ventilation oxygen levels, statistically improved in the CoQ10 group compared with placebo.

CoQ10 can also play a role in angina treatment. CoQ10 (150mgs 3 times daily for 4 weeks) reduced the frequency of anginal episodes by over 50% and the need for nitroglycerine medication compared with patients receiving placebo.243

Statin drugs are known to adversely interact and reduce levels of CoQ10. The statins inhibit the enzyme HMG CoA reductase required for the manufacture of cholesterol in the liver, but by doing so, this blocks the substances required to produce CoQ10. Consequently this may explain the adverse effect of statins such as fatigue and muscle pain which correlates with lowering of CoQ10 levels.244 Supplementation of CoQ10 together with statins may help reduce the risk of these side-effects.

L-carnitine

L-carnitine is an endogenous molecule that is an important contributor to cellular energy metabolism. The concept of modulating the energy metabolism of the heart so as to ameliorate the performance of the dysfunctional myocardium is a firmly established notion.245 Cardiac muscle contains high levels of carnitine and many patients with CVD demonstrate low levels of carnitine.246 A recent review concluded that L-carnitine could prevent apoptosis of skeletal muscle cells and that it has a role in the treatment of congestive heart failure-associated myopathy.247 This has evolved from an emergent literature describing the clinical efficacy of L-carnitine in patients affected by heart disease248, 249, 250 albeit with some controversy.251

Further, cardiovascular function has an intimate relationship with cognition in the ageing process. Recently it has been demonstrated that oral administration of levocarnitine produces a reduction of total fat mass, increases total muscular mass, and facilitates an increased capacity for physical and cognitive activity by reducing fatigue and improving cognitive functions.252

Herbal medicines

A number of supplements including garlic, ginseng, flavonoids plus herbs are likely to have a role in the prevention and treatment of CVD. Interactions may occur when herbal remedies are utilised with prescription cardiovascular medications, however, CAM used alone specifically to treat cardiovascular conditions is a less common occurrence.253 Therefore it is scientifically plausible that, as the evidence becomes available, an integrative approach to the treatment of CVDs should be adopted.

Garlic (Allium sativum)

A double-blind randomised controlled trial of garlic over a 4-year period showed that garlic reduced the development of atherosclerosis, supporting the role of garlic in overall cardiovascular care.254, 255 A recent review found garlic to benefit CVD.256 Garlic can maintain the elastic properties of arteries.257

Garlic can also reduce cholesterol levels and can have a direct beneficial effect on endothelial function, but the data is conflicting.258, 259 Garlic can also inhibit platelet activation, adhesion and aggregation through various mechanisms.46, 260

Ginseng (Panax ginseng)

Ginseng (Panax) has saponins which could act as selective calcium antagonists and enhance release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells, thus providing protection during ischemia or reperfusion.261

Flavonoids

Flavonoids are chemical compounds that are found in the pulp of many plant foods, such as those in blueberries, prunes and cocoa, which have exceptionally high antioxidant activity. Flavonoids have numerous other positive functions including protection from various malignancies and have been reported to delay the development of dementia.262 It is of interest that the phytochemicals present in antioxidant–rich foods such as blueberries may be beneficial in reversing the course of neuronal and behavioural ageing.263

Hawthorn berries (Crataegus oxycantha)

The herb hawthorn, which is rich in flavonoids, has been shown to have a number of beneficial actions, including coronary vasodilation, protection against ischemia-induced arrhythmia as well as high antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.264 Hawthorn has been shown to improve exercise tolerance and decrease the incidence of angina.265 The evidence for hawthorn berries is particularly convincing for the treatment of congestive heart failure according to a recent Cochrane meta-analysis of the literature.266

Red yeast rice extracts (Monascus purpureus)

Red rice has a similar biochemical action to statins where it inhibits HMG CoA reductase and helps to normalise abnormal serum lipids according to a meta-analysis of randomised control trials (RCTs).267 A high dose could cause liver enzyme abnormality similar to statins.47

Red yeast rice extracts have been documented to improve lipid profiles268 and 1 study reported that it was as effective as simvastatin.269 It is interesting to note that simvastatin is also derived from the fungus Aspergillus terreus.

Other heart and vascular diseases

Atrial fibrillation (AF)

Exercise

Regular daily leisurely, light to moderate-paced walking reduces the risk of new-onset AF compared with no exercise, although vigorous, strenuous exercise may increase AF risk especially in young athletes and middle-aged adults.273

Massage therapy

Lymphoedema

Massage therapies such as compression therapy provide a means to treat venous stasis, venous hypertension, and venous oedema. Different methods of compression therapy have been described periodically over the last 2000 years.274 Compression techniques can be static or those utilising specialised compression pumps. The technique of massage called manual lymphatic drainage has emerged to treat primary and secondary lymphoedema.272 Recent reviews have emphasised that there is a need for large controlled trials of the whole range of physical therapies.275

Fish oil supplements

Numerous epidemiological studies, case-control series, and randomised trials have demonstrated the ability of fish oil to reduce major cardiovascular events, particularly sudden cardiac death and all-cause mortality.276 In a study of fish and AF it was demonstrated that in an elderly group of adults, consumption of tuna or other broiled or baked fish, but not fried fish or fish sandwiches, is associated with lower incidence of AF. It was noted that the consumption of fish could influence risk of arrhythmia.277

A review of the evidence suggests fish oils and vitamin C may be useful for the treatment of atrial fibrillation due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory qualities by modulating inflammatory pathways.278, 279

A 3-month study randomised 65 obese sedentary volunteers to tuna fish oil supplements (1·56 g/day of DHA and 0·36 g/day of EPA) and compared them to placebo (sunflower oil).280 The fish oil supplement group reduced heart rate variability and significantly attenuated heart rate responses to exercise, and resting heart rate, thereby reducing cardiovascular risk. According to the researchers, the effects are mediated by modulating parasympathetic activity.

A recent systematic review of the literature of 12 studies inclusive of 32 779 patients for fish oils, found most of the studies reported a significant reduction risk for sudden cardiac death, all-cause mortality and a reduction in deaths from cardiac causes that was dose responsive, but interestingly had no effect on arrhythmias or all-cause mortality.281 No conclusion could be drawn from the studies about the optimal formulation of EPA or DHA.

Fish oil supplements can also help regulate heart rate and are recommended for prevention of both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.246

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption and risk and prognosis of AF among older adults has been reported from the Cardiovascular Health Study.282 Furthermore, recently in patients with CHD, moderate wine drinking was associated with higher marine omega-3 concentrations than no alcohol use. And it was concluded that the effect of wine comparable to that of fish may partly explain the protective effects of wine drinking against CHD.283

Magnesium

A well performed randomised placebo-controlled trial in a hospital setting using intravenous magnesium sulfate (2.5g over a 20 minute period) in addition to usual care, demonstrated enhanced rate reduction and conversion to sinus rhythm in patients who presented acutely with rapid atrial fibrillation compared with standard rate-reduction therapies, such as digoxin.284

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI)

A Cochrane review of the literature identified a number of RCTs and found horse-chestnut seed extract to be efficacious for the symptomatic relief such as leg pain, oedema and pruritus over a short period of time for patients with CVI.285 The adverse events reported were mild and infrequent, including gastrointestinal complaints, dizziness, nausea, headache and pruritus.

Congestive heart failure (CHF)

Obesity

Paradoxically, a cohort of outpatients with established CHF, obese patients with higher BMIs, were associated with lower mortality risks compared with those at a healthy weight.286 All-cause mortality rates increased linearly from 45% in the underweight group to 28.4% in the obese group (P for trend <.001).

Dietary fish consumption

During a 12-year follow-up study of 955 participants, among older adults, consumption of tuna or other broiled or baked fish, but not fried fish, is associated with a significantly lower incidence of CHF.287

Fish oils

A placebo-controlled double-blind trial of up to 7000 patients with symptomatic heart failure from any cause, randomised to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) 1g daily or placebo for a median duration of 3.9 years, found a small but significant reduction in risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalisation.288 The same researchers in a separate study found the statin medication rouvastatin (10mg daily) did not affect the outcome of patients with heart failure.289 Furthermore, there is now strong evidence available that recommends that fish oils should now join the short list of evidence-based life-prolonging therapies for heart failure.290

Fish oil supplementation improved left ventricular function in children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.291

Magnesium

High levels of magnesium orotate (6g for 1 month, then 3g for 11 months) proved to be an effective adjuvant to medical treatment for patients with severe CHF by improving survival rate and improving quality of symptoms and quality of life.292 Another study demonstrated improved inflammatory marker C-Reactive protein in patients with heart failure after treatment with magnesium 300mg daily compared with standard medical care alone.293

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Good quality trials demonstrate CoQ10 improves cardiac function in patients with CHF.

Chinese herb Shengmai

A recent Cochrane review identified 19 trials and found that the Chinese herbs Shengmai plus usual cardiac treatment showed significant improvement in clinical status, reduced risk of mortality, levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and improved hemodynanic tests compared to usual treatment alone for heart failure.294 The reporters did note most trials were of poor quality and no adverse affects were reported in any of the trials. They concluded that Shengmai plus usual treatment may be beneficial compared to usual treatment alone for heart failure, but more long-term, high-quality studies are needed.

Hawthorn berries

A Cochrane review including 14 trials of 855 patients with chronic heart failure found hawthorn extract was more beneficial than placebo for physiological workload capacity, exercise tolerance, and the pressure-heart rate product (an index of cardiac oxygen consumption).295

The patients were also less likely to develop the symptoms of shortness of breath and fatigue with treatment. Adverse events were infrequent, mild and transient such, as nausea, dizziness and cardiac and gastrointestinal complaints. The authors concluded there is a significant benefit in symptom control and physiologic outcomes from hawthorn extract as an adjunctive treatment for chronic heart failure. 295

Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

Natural vitamin E

In the Women’s Health Study, intake of 600IU of natural vitamin E on alternate days over a 10-year period reduced the risk of developing VTE by up to 27% compared with placebo. This was especially the case in those with a prior history or genetic predisposition (either factor V Leiden or the prothrombin mutation), where this risk further reduced by 49%.296

Peripheral artery disease overweight and/or obese

The excess mortality among underweight patients was largely explained by the overrepresentation of individuals with moderate-to-severe COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. COPD may in part explain the ‘obesity paradox’ in the PAD population.297

Arginine

Researchers assessed the effect of 2g or 4g of L-arginine supplementation 3 times daily on nitric oxide (NO) concentration and total antioxidant status (TAS) in patients with atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease over 28 days.298 L-arginine increases NO synthesis. Low NO levels can affect vascular endothelium. Supplementation of L-arginine substantially increased NO and TAS levels, which implies L-arginine has an antioxidant effect and may be effective in preventing CVD.

Stroke

Fruit and vegetables

A meta-analysis identified 8 prospective studies that demonstrated 5 servings of fruit and vegetables daily reduces the risk of stroke by 26%, and 3–5 daily by 11%.299

Music

A randomised study of 60 patients found listening to music in the early stages following a stroke led to greater improvement in memory and attention than those who listened to audio books, or nothing at all.300

Occupational therapy (OT)

According to a Cochrane review of the literature, treatment following a stroke with OT can improve survival length and independence levels compared with no OT.301

Intensive nutritional supplement

A randomised, prospective, double-blind, single-centre study comparing intensive nutritional supplementation to standard, routine nutritional supplementation in 116 undernourished patients admitted to a stroke service, demonstrated patients receiving the intensive supplementation improved measures of motor function (estimated by walk tests) and a higher proportion went home compared to those on standard supplementation.302 However, there were no differences on measures of cognition.

Conclusion

From the foregoing, and emerging aggregate scientific evidence, the prevention and treatment of CV diseases requires a multi-level intervention. A healthy lifestyle plays an important role in the primary prevention of CHD in middle-aged and older men and women.

One notion that has been advanced is that nutritional supplements cannot be patented, hence the lack of funds for costly clinical trials. This lack of funding most probably explains why it is not conclusively known as to whether reduction of homocysteine can influence CVD, despite the increasing data linking hyper–homocystinemia with CVD. An abstract of a study has demonstrated that multivitamins that contain B group vitamins can significantly reduce blood homocysteine in men at risk for CVD as well as improving depressive symptoms.304

The comprehensive cardio-protective lifestyle and supplementation advice suggested by Lewis17 should be part of routine care of patients by the medical profession.

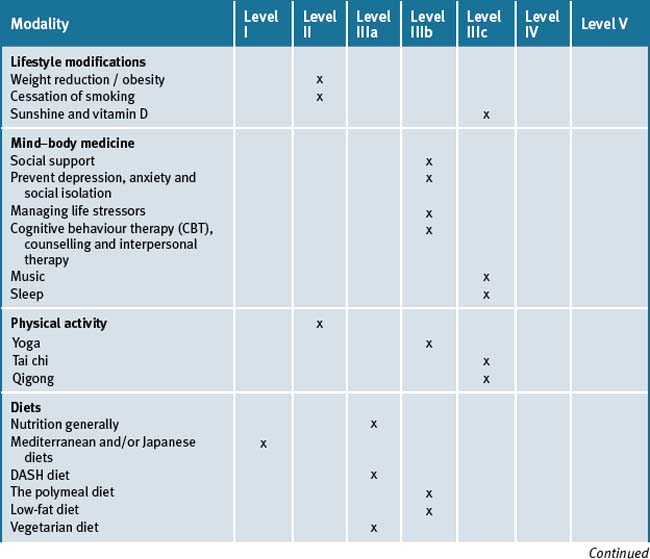

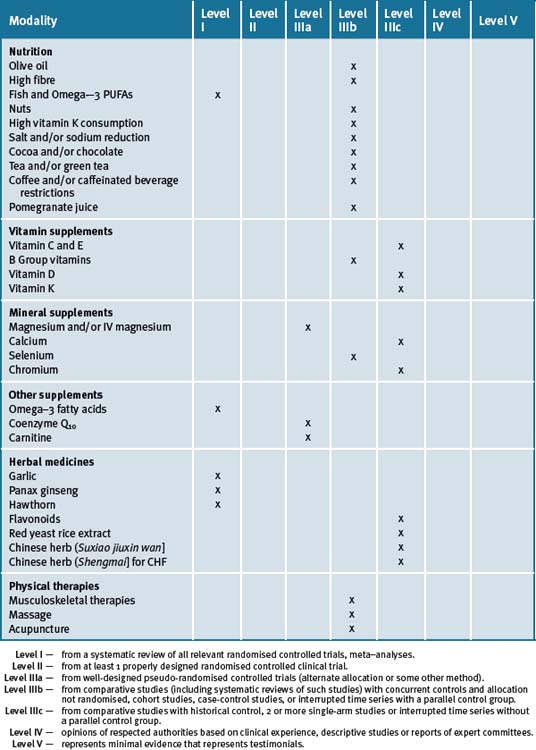

Many patients need continual reminders, education and support in the importance of lifestyle factors contributing to CVD. Chronic disease self-management education programs are important. The integrative medicine approach must always incorporate the evidence-based use of pharmaceutical therapy. Table 10.3 summarises the level of evidence for some CAM therapies for ASD.

Clinical tips handout for patients with cardiovascular disease

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine (most helpful)

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Niacin

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamins B6, B12, Folate (best given together as a multivitamin + mineral)

Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol)

Vitamin C

Natural vitamin E

Magnesium

Chromium Picolinate

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Herbal medicines

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Hawthorn berries

Red yeast rice

1 World Health Organization—Cardiovascular disease: prevention and control 2003.