chapter 10 Cardiovascular Assessment of Infants and Children

Classification of Heart Disease in Children

History of Present Illness and Cardiac Functional Inquiry in the Infant and Young Child

Congenital heart lesions can be divided into three groups:

Age of onset

Significance of the Age of Onset of Congestive Heart Failure

The clinical significance of the age of onset of congestive heart failure is as follows:

Approach to Cardiovascular Examination of the Infant

Because infants and children have an unfortunate habit of not always cooperating, you need to have an organized approach to the cardiovascular examination, while also staying flexible. Do what can be done when the opportunity arises. Begin by assessing the child’s physical development and looking for dysmorphic features, using a systematic approach (see Chapter 5).

Looking for central cyanosis

Because the most pressing clinical problems are congestive heart failure and cyanosis, decide early in the examination whether central cyanosis is present. Because this determination is not always easy, you may find an experienced nurse’s opinion invaluable. Many normal newborns have a deep plethoric appearance as a result of a transiently high hemoglobin concentration, particularly if there was a delay in clamping the umbilical cord. Plethora is not as obvious in the mucous membranes, so look carefully in the baby’s mouth. Deep pressure on the skin may help, because the blanched area does not pink up as quickly in infants with central cyanosis. Many normal infants exhibit a generalized mottling, particularly after being bathed (see Fig. 4-2); this condition is called cutis marmorata (literally, marbled skin) and is not pathologic. It also is common in children with Down syndrome. Observe the effect of crying. Invariably, central cyanosis resulting from cardiac disease increases during crying, but do not make the baby cry until after you have listened to the heart.

Clinical manifestations of heart failure

When low cardiac output and high pulmonary venous pressure cause sufficient hemodynamic disturbance to produce clinical manifestations, cardiac enlargement is invariably present. Whether the disturbance involves primarily the left or the right ventricle, the left side of the thorax becomes prominent anteriorly (Fig. 10–1). Although this prominence may not be evident in the first month of life, it certainly will be evident by the age of 3 months. When respiratory distress due to heart failure has been present for 2 months or longer, the greater diaphragmatic contractions during respiration may produce a sulcus in the lower thorax, with outward flaring of the inferior rib cage edge. Therefore, look for a sulcus, left-sided chest prominence, abnormal chest or abdominal movement, an increased respiratory rate, and subcostal indrawing.

Palpation

Now lay your prewarmed hand very gently on the infant’s chest, remembering that the heart may not be in its normal position. With the tips of the first and second fingers of your right hand, depress the thorax just left of the xiphoid process (Fig. 10–2). Your fingertips are now lying on the right ventricle. A faint impulse is allowable, but if the heart is enlarged, a definite forceful movement will be present. When you perform this maneuver repeatedly in normal infants, you soon will be able to tell the difference between normal and abnormal findings. This distinction will help you make a quick decision about whether the 6-week-old baby who presents with respiratory distress has a cardiac or a respiratory problem.

Now depress the thorax in the apical area. Prominence of the apical impulse is diagnostically less helpful in infants than in older children, except in rare instances, such as in tricuspid atresia in which the right ventricle is hypoplastic. Then palpate in the second interspace at the left sternal border, where a prominent pulmonary artery pulsation may be elicited. Finally, place one index finger carefully in the suprasternal notch (Fig. 10–3), searching first for an abnormal pulsation and then for a thrill. Then work in the opposite direction, searching for thrills and palpable sounds. At this point, you should have made a reasonable appraisal of the child’s cardiac dynamics.

Liver size and position

Whether you are right- or left-handed, stand or sit on the baby’s right side to palpate for the liver. Use the tip of your right thumb and begin well down in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, pressing inward and upward (Fig. 10–4). If the baby has just been fed, do not press very deeply. If the edge of the liver is soft, its margin may be difficult to detect; nevertheless, if the liver is enlarged, you should appreciate a sense of resistance as your thumb tip moves superiorly. If the edge is difficult to feel, use soft percussion, tapping the second digit of your left hand with the second digit of your right hand, beginning low in the right lower quadrant and placing the second digit of your left hand parallel to the liver edge (Fig. 10–5). You should be able to sense the change in the percussion note signifying the liver’s edge. Except in the presence of pulmonary hyperinflation, the edge of the liver normally should not be more than 1 to 2 cm below the costal margin.

Finally, remember that the liver can be ectopic (i.e., on the left side or up in the thorax).

Auscultation

Palpating the femoral pulses

Palpation of the pulses calls for gentleness, persistence, and patience, so make yourself comfortable before you begin. First, remove the baby’s diaper and palpate for femoral pulsations. Many babies do not appreciate having people poke around in their groins and may cry, urinate, or both. Femoral pulses are particularly difficult to appreciate in obese babies; thus, do not rush into a diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta if you have difficulty feeling them. If the femoral pulses are not palpable in an asthenic baby, however, there is cause for concern (see Fig. 4-20). Now palpate both brachial pulses again. If you can detect good brachial pulses and are certain that the femoral pulses are absent or greatly depressed, listen to the heart before measuring the blood pressure and upsetting the baby. Listen particularly for a high-pitched blowing systolic murmur, which is best heard anteriorly below the left clavicle and can be heard clearly in the left axilla and back, medial to the scapula.

Blood pressure

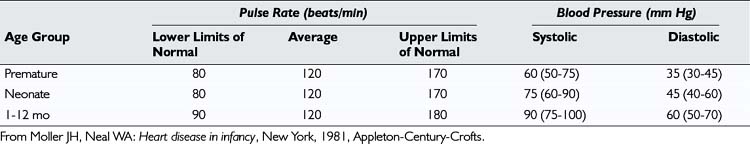

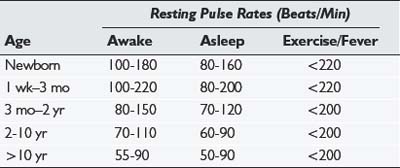

Although measuring the systemic blood pressure can be a difficult task, you should try to do so. The normal systolic blood pressure of an infant is between 60 and 80 mm Hg in both the arm and the leg (Table 10–1). The four methods of measuring blood pressure are (1) auscultatory, (2) palpatory, (3) visual (flush), and (4) Doppler.

For all methods of measuring blood pressure, first supinate the child’s arm to make the radial artery easily accessible. Apply the cuff, elevate the arm, and then inflate the cuff. Prior elevation of the arm (or opening and closing the hand) prevents the auscultatory gap phenomenon (Fig. 10–6). If this procedure is not followed, when you inflate the cuff and listen for Korotkoff sounds, as you decrease the pressure in the cuff you may hear a sound appear, then disappear, and then reappear as the pressure is further decreased. This phenomenon, known as the auscultatory gap, occurs because of increased vascular resistance distal to the cuff.

One way or another, a reliable blood pressure measurement must be obtained. If you suspect an aortic coarctation (i.e., if there is high pressure in the arm, an absence of femoral pulses, and a murmur), repeat the procedure in the thigh, using a blood pressure cuff of an appropriately larger size. Again, the manual Doppler method with the probe held on the posterior tibial or popliteal pulse is our preferred method of measuring blood pressure. The normal range of systolic and diastolic blood pressures for older children is shown in Table 10–2.

Approach to the Cardiovascular Assessment of the Older Child

Syncope

A summary of points to include in the cardiac functional inquiry at different ages is provided in Table 10–3.

TABLE 10–3 Symptoms to Include in Cardiac Functional Enquiry at Different Ages

| Newborn, Young Infant | Older Children and Youth |

|---|---|

| Respiratory symptoms—shortness of breath with feeding or exercise (in toddlers) | Respiratory symptoms—shortness of breath on exertion (at play, gym, when working) |

| Cyanosis—central vs peripheral | Exercise intolerance—inability to keep up with friends and peers |

| Sweats with feeding | Excessive sweating with exercise |

| Duration of and fatigue with feeding | Growth adequacy |

| Growth adequacy | Peripheral edema (periorbital most common) |

| Peripheral edema | Palpitations |

| Recurrent pneumonias | Syncope and nonrotatory dizziness |

| Cyanosis and squatting | |

| Chest pain |

Approach to the Cardiovascular Examination of the 3- to 5-Year-Old Child

General examination, inspection, and palpation

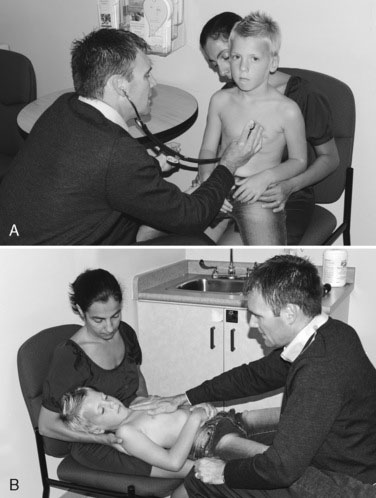

The general examination, inspection, and palpation portions of the examination of a 3- to 5- year-old are similar to those for the infant and toddler. The decision to examine the child while he or she is on an examination table or in the parent’s lap must be individualized; often it is useful to keep the patient in the parent’s lap. Both the parent and child should face you and sit with the child facing forward. As with younger children, you should start by examining the hands and brachial pulses. The transition to a supine position is easy with a child who is facing forward—just raise the legs and pull forward slightly. This position, with the majority of the child’s body still on the parent’s lap, keeps the child comfortable while giving you easy access to the precordium for palpation and auscultation and to the legs for checking the femoral pulses. For children inclined to kick, you can maintain control of the legs by holding them close to your body underneath your arms. These positions are pictured in Figure 10–7.

Heart sounds and murmurs

Heart Sounds

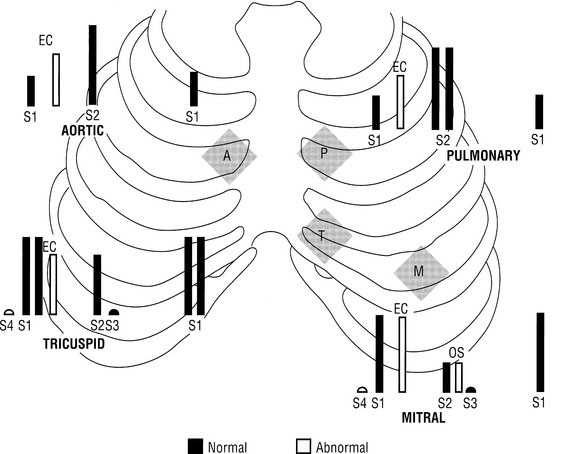

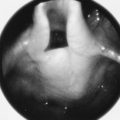

A sound heard at the time of opening of the pulmonary or aortic valve is called an ejection click; when mitral or tricuspid opening is heard, the term opening snap is used. The clicks signal the beginning of ejection into a dilated great vessel; the snaps signal the commencement of diastolic flow into the ventricle. Both are always high-pitched and are loudest over their respective valves, except the aortic click, which is usually heard clearly at the apex. The pulmonary ejection click is unique in that it is loudest or sometimes only heard during expiration. The only hope of identifying these sounds is a thorough working knowledge of what is normal and of what you would expect to hear in a normal infant or child when you place a stethoscope on a particular area of the chest. Normal and abnormal sounds for each listening area are shown in Figure 10–8.

Murmurs

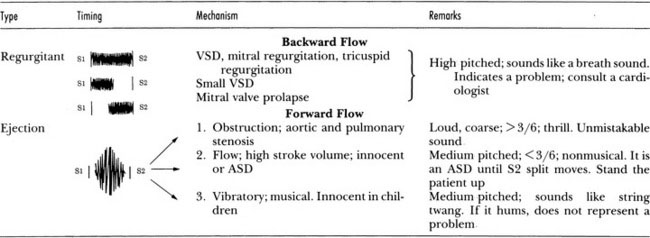

Systolic Murmurs

Ask yourself which mechanism is operating whenever you hear a systolic murmur.

Vibratory Murmurs

The innocent vibratory systolic murmur heard commonly in children probably results from a high stroke volume being ejected forcefully, causing tissue in the left ventricle to vibrate. It is heard maximally in expiration and usually is best heard midway between the left sternal border and the apex. Merely detecting a musical quality of the murmur in children means that the chances are high that the murmur is innocent (Fig. 10–9). When calcium is deposited in a heart valve, the resultant murmur is not just musical; it has high-pitched components. Occasionally, in children who have a perimembranous VSD, the murmur may have a similar high-pitched component, possibly caused by vibration of the membranous portion of the septum.

Continuous Murmurs

Of the many causes of continuous murmurs, only two are of major importance. The most common continuous murmur is a normal finding known as the venous hum. In children whose circulation is hyperkinetic, continuous turbulence is audible over the jugular veins and usually is loudest in the right supraclavicular fossa. This murmur, usually heard only in the sitting or upright position, varies considerably in intensity with movement of the child’s head, and its intensity may be influenced by light pressure on either jugular vein (Fig. 10–10). The turbulence also may be palpated with light pressure on the jugular vein (Fig. 10–11). With light finger pressure, a thrill may be palpable. Occasionally, a venous hum is audible when the child is supine with the head only slightly elevated. This murmur, as common as it is, frequently confounds the examiner, who usually has forgotten the basic rule of first listening with the patient in the supine position.

FIGURE 10–10 The intensity of a venous hum may be enhanced by rotating the head laterally and extending the neck slightly.

Auscultation technique for murmurs

Auscultation of the heart is a difficult skill to acquire. To become proficient requires many hours of listening to hearts, so take advantage of every opportunity you have to do so. Despite their best intentions, most students do not listen to enough hearts to acquire a high level of auscultatory skill. Thus you are thus encouraged to use alternate methods to improve your skills, such as CD ROMs, DVDs, Web-based learning tools, and podcasts (e.g., review EarsOn! at http://earson.ca). Substantial research in cardiac auscultation supports the fact that repetition is the key to success in this area.

Cardiovascular Examination of the School-Aged Child

Observation

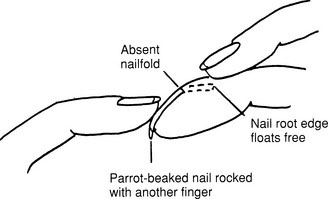

Look at the fingertips from the side (Figs. 10–12 and 10–13). Clubbing occasionally can be normal and may occur in persons with noncardiovascular diseases. Are the fingers of normal length and number? Is there clinodactyly? Dorsiflex the fingers and wrist. Is the tone normal?

Taking the pulses

Start with the brachial pulse, not the radial pulse. The closer to the heart the pulse is felt, the truer its quality. Using the first and second digits of your right hand, palpate the brachial artery, just above the antecubital fossa (Fig. 10–14). In the older child, it may be preferable to support the child’s right arm with your left, using your right thumb to palpate the pulse. The following questions are important:

If the pulse volume seems to be increased, check for a water-hammer pulse by elevating the child’s arm and encircling the upper arm with one hand (Fig. 10–15). A pulse of normal volume is not usually felt with this maneuver. Now dissect the pulse by analyzing the upstroke and downstroke.

If the pulse volume is increased, the child has a hyperkinetic circulation, aortic insufficiency, or a PDA. In such a patient, when blood pressure is measured, the pulse pressure is increased, and when the chest is palpated, the heart action is increased. The pulse quality reflects the manner in which blood leaves the heart and the resistance it meets in the periphery. Now palpate the femoral pulse; if it is of good volume, aortic coarctation is not present. If it is absent or is distinctly smaller in volume than the brachial pulse, the blood pressures in the arms and legs must be carefully measured. As previously mentioned, radial-femoral pulse delay is difficult to elicit (Fig. 10–16), and if aortic regurgitation accompanies coarctation, such a delay is not present.

Pulsus Paradoxus

Check for pulsus paradoxus as follows:

Sinus Arrhythmia

The normal pulse rate varies with respiration, being faster in inspiration and slower in expiration. This normal phenomenon is called sinus arrhythmia. The range of normal for resting pulse rates in children older than 2 years is listed in Table 10–2.

| C | Character |

| L | Location |

| O | Onset |

| R | Radiation |

| I | Intensity |

| D | Duration |

| E | Exacerbating and alleviating factors |

Palpation of the chest and abdomen

When palpating the thorax for ventricular dynamics, remember the following facts:

Cardiac Assessment of the Teenager

Chest pain

Chest pain tends to occur more often in older than in younger children, although some young children also may report having chest pain. The vast majority of episodes of chest pain in children are functional or benign. True cardiac chest pain is distinctly unusual. In exploring the history of pain for an individual patient, you may wish to use the CLORIDE mnemonic (see Table 10–4) or a mnemonic of your own. The CLORIDE mnemonic can be described as follows:

Constant J. 4th ed. Bedside cardiology. Boston: Little, Brown, 1993.

Engle W.D. Blood pressure in the very low birth weight neonate. Early Hum Dev. 2001;62:97-130.

Keith J., Rowe R.D., Vlad P. 2nd ed. Heart disease in infancy and childhood. New York: Macmillan, 1967.

Moller J.H., Neal W.A. Heart disease in infancy. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1981.

Park M.K. Pediatric cardiology for practitioners. St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Roy D.L., McIntyre L., Human D.G., et al. Trends in the prevalence of congenital heart disease: comprehensive observations over a 24-year period in a defined region of Canada. Can J Cardiol. 1994;10:821-826.

The National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-576.