5.4 Cardiovascular assessment and murmurs

Introduction

Approximately 1% of infants and children in developed countries have congenital cardiac problems. The majority are from congenital cardiac abnormalities (see Chapter 5.5). Acquired diseases include myocarditis, pericarditis, cardiomyopathies and coronary vascular disease such as Kawasaki disease (see Chapters 5.6–5.8)

History

The pattern of breathing may provide clues. Increased work of breathing and grunting suggest left-sided obstructive lesions or respiratory illness. Effortless tachypnoea may be found with cyanotic heart disease (see Chapter 1.1).

Physical examination

The peripheral pulses should be examined. Assess the rate, rhythm and character of the pulse. Compare the resting pulse rate to normal ranges for age (see Chapter 1.1). Variation of the heart rate with respiration (sinus arrhythmia) in children is more marked than in adults. The character of the pulse may change with a cardiac defect, surgical treatment or cardiac failure. Bounding pulses are often found in febrile children without heart disease but may be associated with patent ductus arteriosus or a systemic-pulmonary shunt for palliative treatment of cyanotic heart disease with decreased pulmonary blood flow. Reduced volume or delay of the femoral pulses compared with the right brachial pulse suggests coarctation of the aorta. Diffusely small pulses are associated with low-output cardiac failure or shock.

Murmurs should be assessed with regard to their:

Auscultation of the chest should note air entry and presence or absence of crackles.

Chest X-ray

In acyanotic heart disease with left-to-right shunting there may be increased pulmonary vascularity.

Electrocardiography

The ECG is good at detecting hypertrophy and therefore conditions with pressure overload.

Systematically look at the P waves, PR interval, QRS complexes, ST interval and T waves.

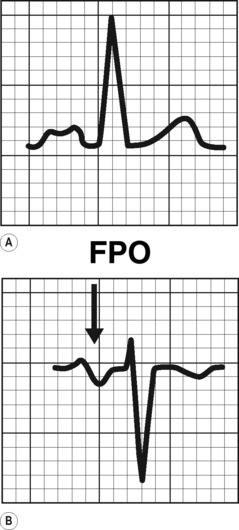

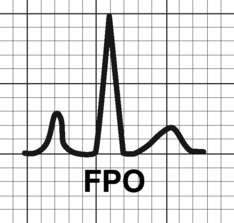

Atrial enlargement

Fig. 5.4.1 Right atrial abnormality.

From Goldberger: Clinical Electrocardiography: A Simplified Approach, 7th ed. 2006. Copyright © Mosby.

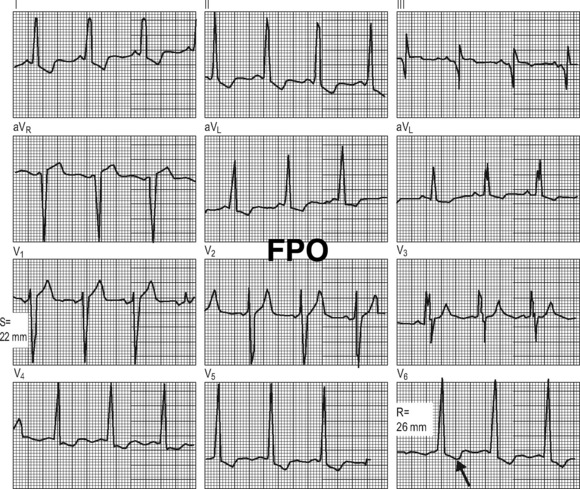

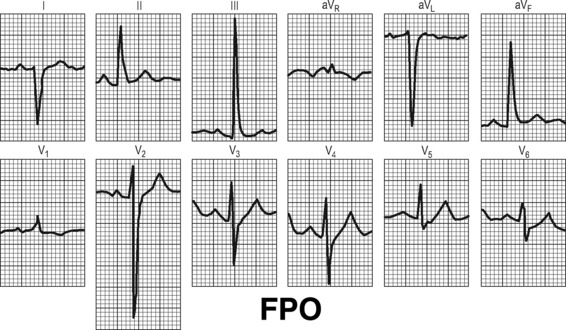

Ventricular enlargement

Right ventricular hypertrophy (see Fig 5.4.3):

Fig. 5.4.3 Right ventricular hypertrophy.

From Goldberger: Clinical Electrocardiography: A Simplified Approach, 7th ed. 2006. Copyright © Mosby