Sometimes examiners like to test candidates’ knowledge of the management of common acute medical conditions. No condition is more common than acute myocardial infarction in the physician trainee’s case repertoire, and the candidate is expected to be thoroughly familiar with the management of this condition.

A 45-year-old man presents with retrosternal chest tightness of 3 hours’ duration. The pain is dull in nature, 7/10 in severity and radiating along the left arm. The onset was at rest. He also complains of progressive dyspnoea and associated nausea. He denies any cardiovascular risk factors apart from a strong family history. On examination his pulse rate is 100 bpm, low in volume and regular. His blood pressure is 90/60 mmHg. There are fine crepitations bibasally in the lung fields. The ECG shows deep T wave inversions in leads I, III and aVF.

Upon stabilisation the patient is admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU). His Killip class is 2 (see box). He is managed on aspirin, metoprolol 12.5 mg twice daily and IV heparin. While in CCU his blood pressure drops to 70/40 mmHg and pulse rate to 40 bpm. His pain is progressive and the ECG shows further deepening of the T wave inversions and new ST depression in the said leads, and also in leads aVR, V

1 and V

2.

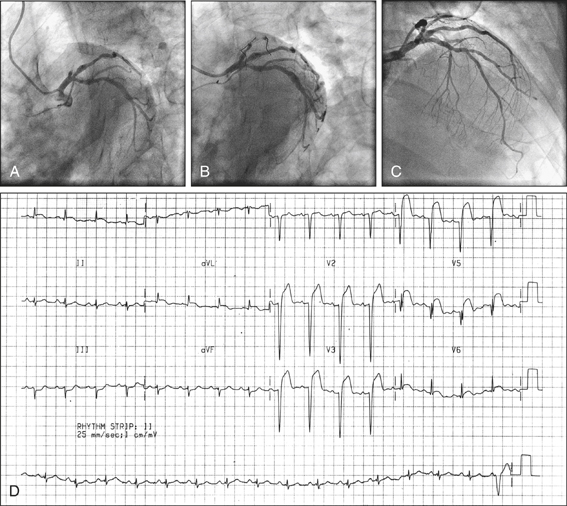

He is commenced on an IV glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor and referred for early catheterisation. Catheterisation reveals occlusion of the posterior descending branch of the right coronary artery, which is successfully reopened by balloon angioplasty and stenting. On day 2 he develops fever and pleuritic chest pains.

On day 3 he develops acute pulmonary oedema and cardiogenic shock. Auscultation reveals a new harsh pansystolic murmur audible all over the precordium.

(Adapted from Killip T, Kimball J T 1967 Treatment of myocardial infarction in coronary care unit. A two-year experience with 250 patients. American Journal of Cardiology 20:457)

(Adapted from Killip T, Kimball J T 1967 Treatment of myocardial infarction in coronary care unit. A two-year experience with 250 patients. American Journal of Cardiology 20:457)

In any acute myocardial infarction the first priority is to assess the patient’s clinical stability and assess the requirement for, and urgency associated with, coronary revascularisation. Remember: patients presenting with an infarction could present with acute pulmonary oedema, cardiogenic shock, malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias or severe bradycardia. Once the patient’s haemodynamic stability and cardiac rhythm stability are established, perform an urgent ECG to confirm the diagnosis and identify the nature of the infarction—whether it is an ST segment elevation infarction (STEMI) or a non-ST segment elevation infarction (non-STEMI).

If the infarction is a STEMI, urgent reperfusion therapy is needed. Acute reperfusion therapy could be primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (primary PTCA) with insertion of a stent or thrombolysis. If the centre offers a primary angioplasty service and the patient fulfils the criteria (see box), urgent transfer to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory should take place. Patients presenting in the first 4–6 hours of onset of chest pain are considered suitable for primary PTCA. Previous coronary artery bypass grafts, peripheral vascular disease, untreatable terminal illness and dementia are exclusion criteria for this procedure.

If primary PTCA is not an option, the patient should be thrombolysed with the relevant thrombolytic agent. If the patient presents within the first hour after the onset of chest pain, thrombolysis would be a preferred option (the ‘golden hour’ phenomenon). Usually a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) or an analogue is given to the patient immediately. Streptokinase is an alternative for patients over the age of 65 or those with evidence of an inferior myocardial infarction presenting after 4 hours of the onset of chest pain. Those who have been treated with streptokinase previously should not be given streptokinase again, due to the heightened risk of an allergic reaction.

The ECG criteria for primary PTCA and thrombolysis are similar (see box), but thrombolysis may be useful up to 12 hours or even 24 hours after the onset of chest pain.

If the decision is made to administer thrombolytics, the patient should not have any contraindications (e.g. risk of haemorrhage or allergy) to such therapy. If thrombolytic therapy has not been effective and the patient is a strong candidate for reperfusion therapy, attempts should be made to organise urgent rescue angioplasty.

If a non-STEMI, the patient should be managed initially with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. The patient should subsequently be referred for early coronary catheterisation.

Patients with acute coronary syndrome benefit from IV antiplatelet therapy in the way of platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents such as tirofiban or eptifibatide in addition to heparin.

The patient should be admitted to the CCU for continuous ECG monitoring. Serial cardiac enzymes or troponin levels should monitored. Patients who sustain right ventricular damage may become profoundly hypotensive. They need IV volume infusion as the first line of therapy. Those in cardiogenic shock require inotropic therapy in the form of IV dobutamine or dopamine to support cardiac function and haemodynamic stability.

Ventricular fibrillation within the first 24 hours of an infarction indicates a more favourable prognosis than those occurring afterwards. Episodes of ventricular fibrillation after the first 24 hours signify a guarded prognosis, and consideration should be given to the implantation of a cardiac defibrillator. Inferior or posterior myocardial infarctions can damage the AV node or the cardiac conduction system, leading to heart block. These patients need urgent insertion of a temporary pacemaker. Some may recover their nodal and conduction function as the oedema and inflammation associated with the acute event settles, but others who sustain permanent damage need insertion of a permanent pacemaker (PPM). Complete heart block in a patient who suffers an anterior myocardial infarction signifies a bad prognosis due to the extensive area of myocardial damage.

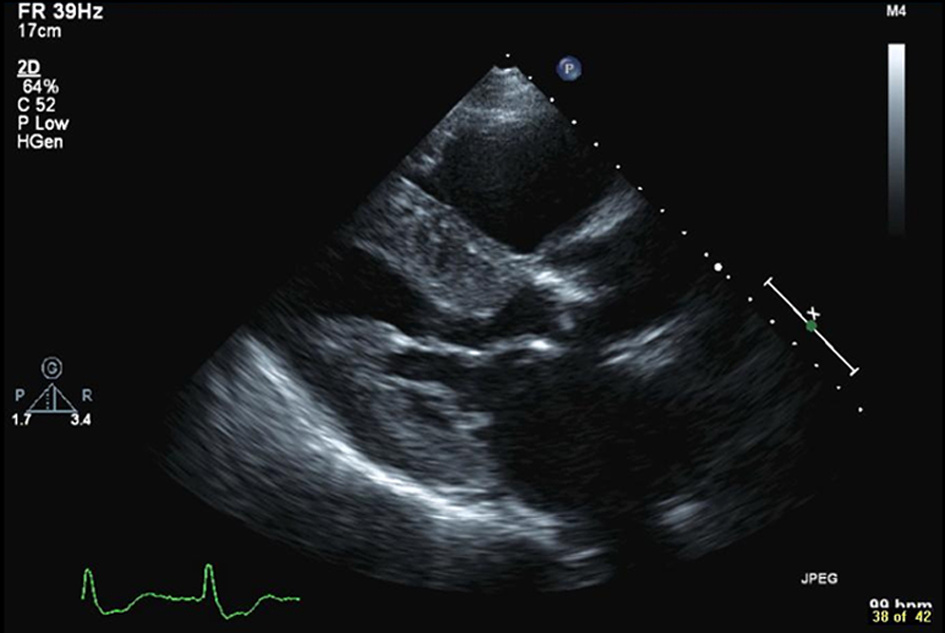

Follow-up management includes a transthoracic echocardiogram to assess the ejection fraction and to look for segmental left ventricular wall motion abnormalities, valvular defects, ventricular septal defect, ventricular thrombus and ventricular aneurysms. Ejection fraction can also be assessed by performing a nuclear gated heart pool scan. Patients who have an ejection fraction of less than 40% after an infarction are at high risk (30%) of sudden cardiac death over the next 5 years. These patients qualify to be treated with a prophylactic implanted cardiac defibrillator (ICD) usually 40 days after the infarction, according to current evidence.

Patients suffering from post-infarct angina need early coronary angiography to define the coronary anatomy before deciding on definitive therapy. Stable patients should have an exercise stress study, looking for reversible ischaemia. This may take the form of a stress echocardiography, stress ECG or nuclear medicine perfusion study. The presence of reversible ischaemia or ischaemia associated with stress are indications for coronary angiography. Definitive treatment with angioplasty, with or without stenting of the involved artery, or coronary artery bypass grafting, should be decided upon as guided by the coronary anatomy.

Prior to discharge, patients should be recruited to a post-myocardial infarction rehabilitation program and modification of cardiovascular risk factors should be encouraged. Some patients may need counselling and significant reassurance to help them recover from the acute event. Others may need advice on lifestyle and occupational issues, relevant information and education, counselling on sexual matters, dietary advice, help with giving up smoking and partner counselling.