chapter 25 Cardiology

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Cardiovascular disorders are encountered very frequently in the primary care setting. In developed or affluent countries, cardiovascular disease is still the most common cause of mortality, accounting for 38% of all deaths,1 and a significant cause of disability, particularly due to cerebrovascular disease and congestive cardiac failure. One in five Australians are affected by cardiovascular disease.2 Cardiovascular disorders are due to pathologies that arise in the:

THE INTEGRATIVE APPROACH IN CARDIOLOGY

In 2005 the American College of Cardiology published an expert consensus document titled, ‘Integrating complementary medicine into cardiovascular medicine’.3 The authors noted that there was considerable debate regarding the clinical utility of alternative medicine practices, that these practices were widely employed by patients with cardiovascular disease and that there was a need for further research. The authors noted that ‘integrating CAM into medicine must be guided by compassion, but enhanced by science and made meaningful through solid doctor/patient relationships. Most importantly CAM involves a commitment from the clinician to the caring of patients on a physical, mental and spiritual level’.3a

ASSESSMENT OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

CARDIOVASCULAR HISTORY

CARDIOVASCULAR EXAMINATION

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT OF THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM IN PATIENTS PRESENTING WITH POTENTIAL CARDIAC EVENTS

Urgent steps to be taken in this setting include the following:

Once the patient’s clinical stability is established, a more thorough assessment can be started.

CARDIOVASCULAR INVESTIGATIONS

Following is a list of common cardiac investigations with indications:

RISK FACTORS FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Modifiable coronary risk factors include:

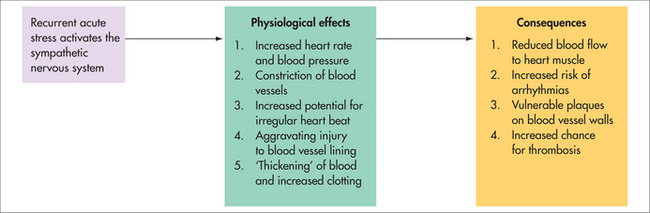

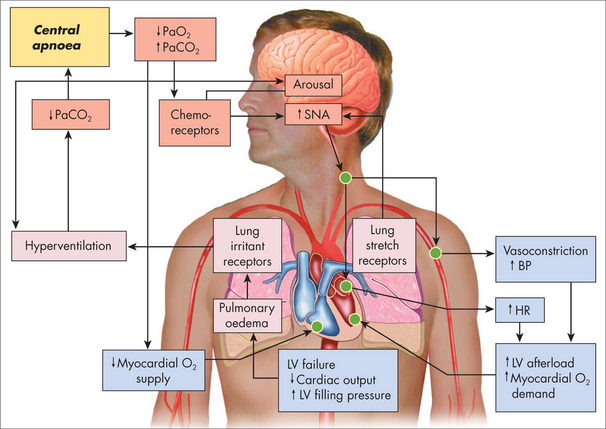

Psychological factors such as chronic stress and depression can contribute significantly to the aetiology and progression of cardiovascular disease, largely due to their association with sympathetic nervous system over-activation and high allostatic load. These effects are summarised in Figure 25.2.

PRIMARY PREVENTION

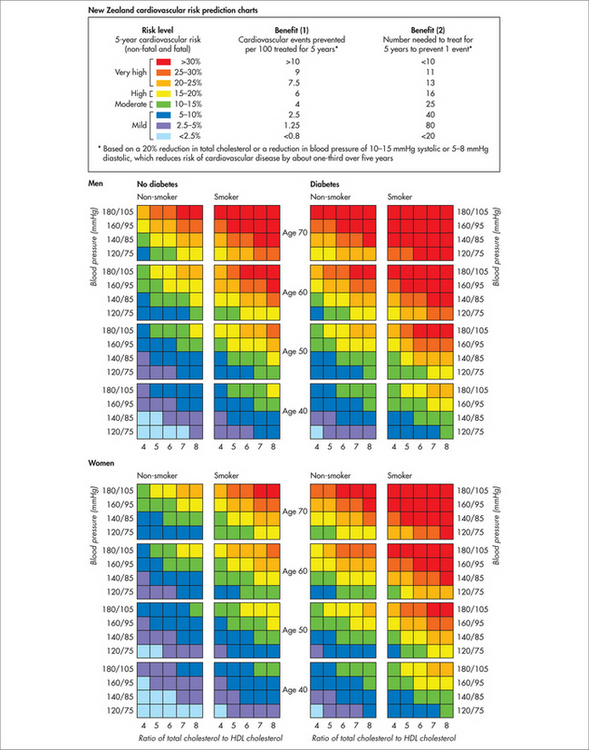

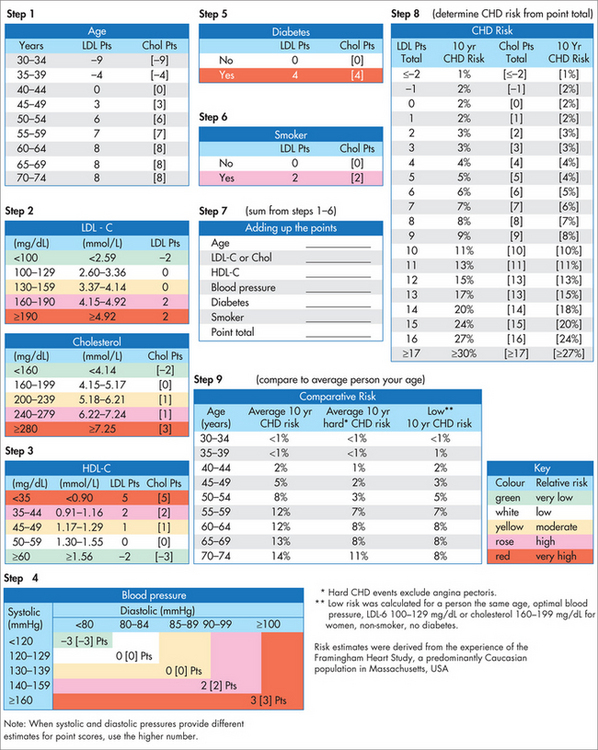

Primary prevention of acute myocardial infarction requires first and foremost the clear identification of the patient’s global risk factor profile. Once this is accomplished, the patient’s risk level can be quantified using a coronary risk calculator. The New Zealand risk score and the Framingham risk score are two such practical tools widely used in the primary care setting (Figs 25.3 and 25.4).

DIABETES MELLITUS

HYPERCHOLESTEROLAEMIA

| total cholesterol level | < 4 mmol/L |

| LDL cholesterol level | < 2.5 mmol/L |

| HDL cholesterol level | > 1 mmol/L |

| TG level | < 1.5 mmol/L |

HYPERTENSION

Left untreated, hypertension can lead to disorders of various organ systems (target organ damage).

Investigations

Management

A medication review for pro-hypertensive agents (see Boxes 25.1 and 25.2) needs to be performed.

First-line

Dose: 100–150 mg daily; well tolerated and no known cardiac interactions.

Pharmaceutical

Common pharmaceutical agents used in the treatment of hypertension:

POOR MENTAL HEALTH

Psychological strategies that are effective in improving mental health have also been shown to be associated with a reduced incidence of recurrence and cardiac mortality. Including psychological and social support in the management of heart disease produces major reductions in disease progression and the number of deaths.20 A review of the evidence by Linden and colleagues found that, compared to those who were given psychosocial support, those with no such support were 70% more likely to die from their heart disease and 84% more likely to have a recurrence.20 Managing depression with antidepressants has not been shown to produce a significant reduction in cardiac risk and, in fact, many of the earlier classes of drugs increased cardiac risk.

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

ISCHAEMIC CHEST PAIN

Chronic stable angina

History

Investigations

Perform a standard cardiovascular examination.

Management

Acute coronary syndrome: unstable angina and myocardial infarction

History

Examination

Investigations

Management of acute myocardial infarction

Preparation for coronary artery bypass surgery

In recent years the increasing incidence of high-risk and elderly patients presenting for major surgery has presented a challenge for surgeons, due to the associated increased mortality and complication rate and costs. Novel ways need to be found to improve the results of surgery in these patients. Over the past 10 years at the Alfred Hospital and the Baker Heart Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, researchers led by Professor Franklin Rosenfeldt have developed regimens of metabolic therapy with the pyrimidine precursor, orotic acid, and the antioxidant and mitochondrial respiratory chain component, coenzyme Q10.24 Using test tube studies, animal models and human studies, they have shown that these regimens improve the response of the ageing and failing heart to hypoxia, ischaemia/reperfusion injury and aerobic stress such as occur during cardiac surgery.24–29 To these original regimens, omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil supplements) and the antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid were added in an attempt to provide better clinical outcomes. The use of coenzyme Q10 supplementation as standalone treatment was validated in a clinical trial, and the entire combination of therapeutic strategies in a 1-year pilot study.25,26,30 Compared with placebo, treated patients demonstrated improved energy production in the heart muscle, increased resistance to hypoxic stress, one-day shortened hospital stay and improved postoperative quality of life.

It is on this basis that Dr Lesley Braun and Professor Franklin Rosenfeldt developed the Integrative Cardiac Surgery Wellness Program at the Alfred Hospital, which builds research conducted on site and published studies and meta-analyses demonstrating the benefits of such programs.31–34 It also incorporates research produced by hospital-based integrative cardiology and health promotion units already established in the United States (such as the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic).

ARRHYTHMIAS

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia

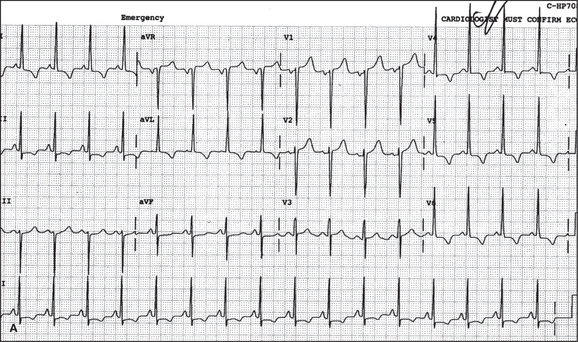

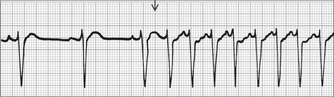

Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) is usually a narrow complex tachycardia, although aberrant conduction may give rise to a wide complex. Based on the site of onset, SVT is classified as atrial, atrioventricular nodal (AVN) or junctional (Fig 25.6).

Investigations

Management

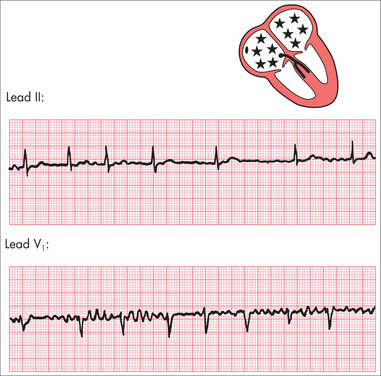

Atrial fibrillation

BOX 25.3 CHADS2 score

(adapted from Gage et al 200135)

| Risk factor | Score |

|---|---|

| Heart failure | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Age 75 or above | 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Stroke/TIA | 2 |

Investigations

Management

Management of AF has three immediate objectives: rate control, rhythm control and stroke prevention.

Surgical maze procedure is another option for resistant cases.

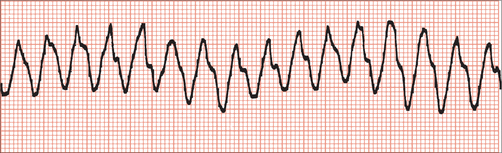

Ventricular tachycardia

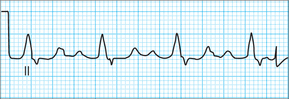

Ventricular arrhythmias are often of greater concern because of their association with haemodynamic instability. They need rapid recognition and management. An ECG of VT is shown in Fig 25.8.

Management

Integrative medicine and arrhythmias

There are a range of options for the integrative management of arrhythmias that may be used as an adjunct to conventional treatments and to reduce complications and relapse.36 For example, omega-3 fatty acids (fish oils) are useful, and populations with a high fish intake have lower incidence of coronary heart disease and death. Omega-3 fatty acids have anti-arrhythmic effects and have been shown to reduce sudden death from VF. Fish oils have also been shown to reduce the incidence of post-coronary artery bypass AF. Supplementation with coenzyme Q10, L-carnitine and selenium might also be useful. The role of potassium and magnesium is promising. Stress, through raised SNS activity, has also been shown to increase arrhythmic potential and so stress reduction should be considered a core element of the management of any serious arrhythmia.

Sick sinus syndrome

CONGESTIVE CARDIAC FAILURE

History

BOX 25.4 NYHA functional classification of patients with heart failure

| III A | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary activity causes undue fatigue, palpitations or dyspnoea. |

| III B | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but minimal exertion causes undue fatigue, palpitation or dyspnoea. |

Physical examination

Investigations

Long-term management of cardiac failure

DIASTOLIC CARDIAC FAILURE / HEART FAILURE WITH NORMAL SYSTOLIC FUNCTION

Common causes of diastolic failure are:

Investigations that should be requested for patients with diastolic cardiac failure are:

ACUTE DECOMPENSATED CARDIAC FAILURE (ACUTE PULMONARY OEDEMA)

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT OF HEART FAILURE

The most recent effective therapy in patients with heart failure is another herbal preparation, hawthorn. Over the past few decades many small trials have shown improved symptoms and heart function with various hawthorn preparations.37 More specifically, a highly purified extract, Crataegus (WS1442), at a dose of 450 mg b.i.d. in addition to standard drug therapy, reduced cardiac-related deaths by 20%. This was in the SPICE trial, which was inducted in 156 centres in Europe and involved 2681 patients with severe impairment of left ventricular function documented by echocardiography.38 Background therapy included ACE inhibitor therapy in greater than 80%, beta-blocker in greater than 60%, α2-antagonists in approximately 70% and spirinolactone in approximately 40%. The beneficial results in addition to standard therapy were on a background of a number of small randomised trials which showed improvements in patients with heart failure. Hawthorn extract has many potential compounds responsible for the beneficial outcome, including ACE inhibitor type activity and anti-inflammatory action.

Coenzyme Q10 has also been used for more than 20 years, and in a number of small randomised trials many patients showed subjective improvement in symptoms, and in earlier studies showed improvement in heart function, although its role in benefiting heart function is still being fully established.39 However, the most rigorous newer trials have not shown benefit in heart function. In one trial that involved patients with significant heart failure, the addition of coenzyme Q10 led to a 38% reduction in the need for hospitalisation due to heart failure during the trial period. Coenzyme Q10 may also be useful as an antihypertensive agent.40,41

Until recently, there has been considerable controversy regarding the need for coenzyme Q10 supplementation in patients on statins. There is no doubt that statin therapy lowers serum coenzyme Q10, as the carrier molecule LDL cholesterol is lowered by statin therapy. Patients on statins, however, have a lower incidence of heart failure, and a recent randomised trial in patients with heart failure showed decrease in cardiovascular events, although no improvement in heart failure.42 Occasionally in patients on statin therapy, coenzyme Q10 supplementation eases aches and pains. Interestingly, in the Australian Lipid Trial, serum coenzyme Q10 levels did not predict cardiovascular outcomes during the 6-year follow-up after the index coronary event.40

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST ENDOCARDITIS

PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE

Ginkgo has been used for the relief of intermittent claudication. In a meta-analysis of eight randomised trials, a dose ranging from 120 to 600 mg per day was used, and overall there are reports of a significant increase in pain-free walking distance.43 The clinical relevance of this increase is unclear, but it is similar to drug therapy, which has not been very successful in this difficult group of patients. Some studies have shown improvement in lipid profile and, surprisingly, it may increase blood pressure in patients taking thiazide diuretics.

PADMA® 28 is a traditional Tibetan preparation. Seven randomised clinical trials have shown significant improvement in walking distance with this preparation. Many studies have shown improvement in lipid profile, and lowering of blood pressure may occur.44 No significant drug interactions are known. There is also some evidence that it may reduce angina.

CARDIAC REHABILITATION

In phase 1 of the program, which takes place immediately after the index event (often at the hospital), a nurse educator provides essential information and education to the patient on the disease condition, risk factor control and lifestyle modification. The patient may undergo an exercise stress test to ascertain the level of effort tolerance that helps develop individualised exercise prescription.

THE ESSENCE MODEL IN MANAGING CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Stress management

Information on the effects of stress on the heart and cardiovascular system is given in preceding sections of this chapter. Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) over-activation, acutely and chronically, increases the risk of cardiac events and accelerates the progression of cardiovascular disease. Autonomic nervous system activation in negative emotional states is an unbalanced one, being nearly all SNS, whereas in positive emotional states it is a far more balanced one between SNS and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which is cardio-protective.45 Anger, for example, was reported by over one in six heart attack patients in the 1–2 hours before a cardiac event. Acute anger more than doubled the risk of having a heart attack. It was also found that anger is more common in younger and socioeconomically disadvantaged patients who present with heart attacks.46 Stroke is also closely related to levels of anger, especially for men who are not able to control their anger. Men who express more anger have double the chance of having a stroke, but the risk grows to seven-fold for men with a previous history of heart disease.47 There is also an increased risk of stroke for those with chronic anxiety, panic disorder48 and depression.49

The term ‘vital exhaustion’ is used to denote the long-term effects of over-activation of the SNS. Vital exhaustion among men was gauged by their response to the statement, ‘At the end of the day I am completely exhausted mentally and physically.’ This is an extremely useful question to add to the history-taking of a person at risk of CVD. If a man said that that statement accurately described his typical daily experience, then over the following 10 months he would be nearly nine times as likely to die from a cardiac event. Even three and a half years later the risk was still three times higher.50 The figures for women may be similar, although they are unlikely to be as high. When followed for 18 months after coronary angioplasty, the risk for new cardiac events for those with vital exhaustion is tripled.51

Reviews of the medical literature find consistent data linking chronic depression, anxiety, work stress and social isolation to heart disease risk and progression.52,53 Rosanski and colleagues relate CVD risk to five specific psychosocial domains: depression, anxiety, personality factors and character traits (principally anger and hostility), social isolation and chronic life stress.47 The relationship is less strong for type A personality.54

More importantly, this increased risk is reversible. A review of 23 studies on including psychological and social support in the management of heart disease clearly showed major reductions in morbidity and mortality if people had psychological and emotional support as a part of their management.55 Compared with those who were given psychosocial support, those with no such support were 70% more likely to die from their heart disease and 84% more likely to have a recurrence. The researcher’s conclusion was unambiguous: ‘The addition of psychosocial treatments to standard cardiac rehabilitation regimens reduces mortality and morbidity, psychological distress, and some biological risk factors. … It is recommended to include routinely psychosocial treatment components in cardiac rehabilitation.’

Although being unemployed is associated with a higher incidence of heart disease, so too is having long working hours, especially under high pressure. The effects of over-employment can be as harmful as those of under-employment.56 Low job control, often associated with low socioeconomic status, and ongoing work stress produce the biochemical and physiological changes which make heart attacks more likely to happen.57–59

Meditation, as a means of activating the relaxation response, is also being investigated as a treatment for CVD and risk-factor reduction. A series of studies on the effects of transcendental meditation (TM) over 7 months found not only a significant reduction in blood pressure60,61 but also reversal of atherosclerosis over the following 9 months.62 The improvements were not attributable to changes in other cardiovascular risk factors such as diet and exercise. The effects of just 9 months of practice translated into reductions in the risk of heart attack by 11% and of stroke by 15%. In another study on the 7-year effects of TM on the elderly63 it was found that the TM group had a 23% reduction in the risk of death from any cause, a 30% decrease in risk of death specifically from CVD and a 49% decrease in risk of death from cancer.

Spirituality

Spirituality is an important part of many people’s ability to deal with stress, depression and hostility. It has been found to be associated with a significant reduction in allostatic load, biological markers of stress and cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, waist/hip ratio, blood fats, markers of diabetes, cortisol and adrenaline levels.64 The effect was much more prominent among women. Among religious attenders there is also a lower level of inflammatory markers relevant for CVD such as C-reactive protein and fibrinogen.65 Reviews of the research suggest that overall religious attendance promotes better health, including a reduced risk of heart disease,66 although some studies have raised doubts about whether there is a cardiovascular protective effect for religious attendance that is independent of lifestyle and social factors.67 If indeed there is an effect, it is probably a combination of lifestyle, social support, better emotional health in terms of coping with anger or depression and the protective effect of religious practices such as prayer or meditation.

Exercise

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death in the industrialised/affluent world. Inactivity by itself results in a 1.5 to two-fold rise in the risk of CVD68 and a three-fold increased risk of stroke.69 Physical exercise protects the heart in a number of ways, apart from helping to facilitate other healthy lifestyle choices. In the long term it leads to:

Being fit also helps in the case of having an acute cardiac event. The risk of death from that heart attack is halved if the person has recently been involved in regular, moderate physical activity. Although regular exercise in the long term clearly reduces the chances of having a heart attack, very vigorous physical exertion, particularly in those not used to it, increases the risk by three and a half times.21,78,79 It is therefore important, especially if older, unfit or unaccustomed to regular exercise, to initially take things gently and build up slowly.

For each MET (metabolic equivalent: a measure of energy expenditure) increase there is an approximate 4% reduction in cardiac risk. Walking slowly consuming roughly 2 MET per hour, walking briskly 4 MET and jogging nearly 9 MET. Higher-intensity activities are associated with lower risk of heart disease.80 The Women’s Health Initiative Observational study looked at over 70,000 postmenopausal women and found that the number of MET-hours per week was inversely associated with heart disease risk.81,82 Most of the emphasis has previously been on the importance of aerobic exercise but the risk of heart disease is reduced by nearly a quarter if weight or resistance training as well as aerobic exercise is included in one’s exercise routine.83 Resistance training is particularly helpful in metabolic syndrome because it helps to build muscle mass, which is like a ‘metabolic sink’ for blood fats and glucose. It may also be the preferred option to aerobic training for those who have a low threshold for inducing angina.

Heart failure is the most common reason for hospitalisation in people over 60 years of age. Traditionally, bed rest was advised for heart failure but we now know that a graded exercise program is associated with better vitality, reduced disability, fewer symptoms and better quality of life for heart failure patients.84 In heart failure patients, exercise also results in improved blood flow, reduced enlargement of the heart, improved heart output, improved function of blood vessel lining and better autonomic function.85,86 The recommended intensity for heart failure patients is 50–70% of VO2 max—that is, ‘walk & talk’ level. If a patient cannot talk while they walk, they should slow down a little.

Nutrition

Nutrition and supplements

Coronary heart disease is almost entirely due to atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries. Rupture of a plaque in the coronary arteries is a pathological event underlying key coronary syndromes, sudden death, acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina. Lifestyle factors, particularly diet, play a role in the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis. Diet has a significant effect on serum lipids and can affect other risk factors such as blood pressure and haemostatic factors. In the 1950s it was clearly documented that saturated fat is the major dietary macronutrient that modifies serum cholesterol and particularly LDL cholesterol.

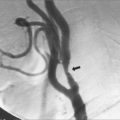

An elevated LDL cholesterol level is the sine qua non for the development of atherosclerosis. Approximately 30 trials have now demonstrated by repeat angiography with or without intravascular ultrasound that lowering LDL cholesterol stabilises plaques and can lead to regression of atherosclerosis.87 When on treatment, LDL cholesterol is < 2 μmol/L. After 2 years, two-thirds of patients show regression of plaque volume of more than 10%. This translates into fewer coronary events and fewer strokes, and greater survival.

There are a number of healthy diets, with the best-researched being the Mediterranean diet. A Mediterranean diet low in saturated fat, rich in monounsaturated fat, fibre, vegetable proteins, regular nut consumption and with moderate intake of alcohol not only lowers LDL cholesterol but independently of this can decrease the risk of coronary events. The famous Lyon Diet Trial of the Mediterranean diet showed a decrease in mortality of 56% compared with the usual low-fat diet.88 The benefit was independent of drug therapy and is in fact greater than seen with cholesterol reduction using statin therapy. However, more long-term follow-up data is required, to confirm these findings. In contrast, the larger Lipid Trial is a typical statin trial with follow-up to 6 years. A 20% cholesterol reduction was associated with a 24% reduction in mortality.89

Nutraceuticals were first defined in 1979 by Steven DeFelice as:

food, or part of food, that provides medical and health benefits to cumulative prevention and/or treatment of disease. Such products may range from isolated nutrients, diet supplements and foods that are genetically engineered, herbal products.90

Nutraceuticals have been endorsed by the American Heart Association (Adult Treatment Panel III) as lowering LDL cholesterol, plant sterols/stenols and soluble fibre.91 Plant sterols and stenols are available in margarine, yoghurt and milk. The dose is 2–4 g per day, and on average the LDL decreases by 10%. Some patients may have zero response and others may have up to 30% lowering of LDL. Plant sterol enrichment also has an additive effect to statin therapy. Soluble fibre (most commonly Psyllium husk) at a dose of 2 tablespoons per day can lower LDL by about 5%. It can be combined with other nutraceuticals and/or statins.

Garlic potentially affects serum lipids, platelet aggregation, blood pressure and blood glucose. In recent reviews, moderate short-term effects of diet supplementation were noted, although findings in all trials have not always been consistent.92,93 This may relate to the differences in concentration of active components between test substances. Soy-based foods have cholesterol-lowering effects and antioxidant properties. A meta-analysis of 38 trials of soy protein demonstrated a reduction of LDL cholesterol of 12% and lowering of triglycerides by 10%.94 Extracts of soy, and in particular isoflavones, seem to have no effect on serum lipids.

In the literature there are many extravagant claims of the beneficial effects of various citrus flavonoids, mushroom extract, olive leaf extract, guggulipid, artichoke, spirulina and policosanol. Almost all the supporting data come from small studies using various animals; randomised clinical controlled trials have rarely been conducted in humans. Policosanol is a sugar cane extract and contains a mixture of aliphatic alcohols. A number of published trials initially showed significant benefit in lipid lowering with 15–20 mg per day.95 LDL decreased by 20–30%, and HDL increased from 8% to 15%, although more recent trials have cast doubt on those initial findings.

Fish oil or, more specifically, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosapentanoic acid (DPA) is effective in lowering triglycerides. Marine lipids have no benefit in lowering LDL. High doses of marine ω-3 lipids may increase LDL. The usual-strength fish oil capsules contain 300 mg of combined EPA and DPA. A more concentrated super-strength form, containing 600 mg or more of combined EPA and DPA, is now available. The starting dose for lowering triglycerides is four 1 g capsules, up to 12 capsules per day.96 Fish oil used in this combination is as effective as fibrates in lowering triglycerides and has an additive effect.

Fish oil prevents sudden death in patients post infarction, and at a dose of two 1 g fish oil capsules per day there is significant decrease in sudden death within a few months post infarction. In the GISSI-P trial 11,324 patients within 3 months of a heart attack were randomised to fish oil (one superstrength capsule) per day or not, and followed for 3.5 years.97 Independent of drug therapy, diet or any other risk factors, those randomised to fish oil had a 41% reduction of mortality in 3 months due to a large reduction of sudden death (53% reduction at 4 months).

These favourable results were confirmed by the Japanese JELIS trial.98 In this trial, 18,645 patients, 2500 of whom had a history of heart disease, were commenced on statin therapy and randomised to high-dose EPA or not. At a 4.6 year follow-up there was a significant 20% reduction in the combined cardiovascular end point of sudden death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina or revascularisation, with fish oil supplementation. This was on the background of a group of patients with a high intake of fish. Fish oil has a number of potential mechanisms for cardiovascular prevention, including an antiarrhythmic effect, triglyceride-lowering effect, anti-inflammatory effects, and it improves mood, endothelial function, lowers blood pressure and slows heart rate.

The American Heart Association in 2002 recommended that all patients with coronary heart disease have at least 1 g of combined EPA and DPA per day, which in practice means supplementation.99 The Australian National Heart Foundation’s position, released in 2008, is consistent with that of the United States.19

Vitamins

The best-studied vitamins in relation to vascular disease are vitamins E and C, folic acid100 and vitamin B3. Vitamin B3 (or nicotinic acid, or niacin) is a mainstream therapy for LDL reduction. Nicotinic acid was noted in the 1950s to be effective in lowering serum cholesterol, lowering triglycerides and increasing HDL. Unfortunately, the therapeutic dose is 3 g per day, and 75% or more of patients cannot tolerate this dose, due to severe flushing.101 In addition, the tablet size is 250 mg and is not as widely available. It is still popular in the United States, particularly in slow-release preparations, because it is relatively cheaper to prescribe.

The most recent update on vitamin supplements in cardiovascular disease by the American Heart Association was in 2004. Epidemiological studies have suggested potential benefit with high natural vitamin E intake or supplements, although the overview by the American Heart Association was that the existing database did not justify routine use of antioxidant supplements for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease.102 However, specific trials that have used natural vitamin E at high dose (greater than 500 IU per day)—and composed of alpha-tocopherol and various levels of gamma-tocopherol and perhaps tocotrienols—have shown a decrease in cardiovascular events in patients on renal dialysis and regression of carotic and coronary heart disease. In contrast, when vitamin E is used in combination with beta carotene, other studies suggest there may even be an increase in mortality.

Elevated homocysteine is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, more than five large randomised trials have not shown a benefit, despite significant lowering of homocysteine by 20% or more, with combination B vitamin therapy.103 There is general consensus now that homocysteine is a marker of increased cardiovascular disease, but it is no longer a target for therapy.

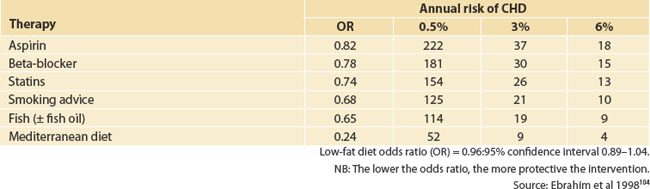

A few years ago, a comparison was made of major mainstream drug therapy and complementary therapies in the prevention of recurrent coronary events in patients with cardiovascular disease. In fact, the most effective therapies were the Mediterranean diet and fish oil supplementation (see Table 25.1).

Connectedness

Cardiovascular risk reduction is taken up differently by different social groups, with the taking up of healthier behaviour conferring greater benefits on those in higher socioeconomic groups.105 Those from lower socioeconomic groups are far less likely to make healthy lifestyle changes, perhaps because of lower autonomy, greater job stress, less education and greater exposure to negative influences such as the higher concentration of fast-food outlets in lower socioeconomic areas.106 A US taskforce looking into predictors for CVD found that job dissatisfaction and unhappiness are stronger predictors than the usually accepted risk factors.107

Some social factors have protective effects on the risk of CVD, including being married (provided it is at least moderately happy), having an extended network of friends and family, church membership and group affiliation.108 Social disadvantage and social isolation are not only predictors of CVD but are also predictors of poor outcomes post-stroke.109 The risk for CVD in later life may be significantly affected by our social and emotional circumstances early in life.110 A study of childhood loss found that the effect of relationships early in life affects how we respond to stressors and the level of SNS activation later in life.

Environment

Environment can affect CVD in many ways. For example, living in a heavily air-polluted urban environment significantly increases the risk of CVD,111 whereas regular moderate levels of sun exposure are associated with a reduced risk of CVD, probably because of increased levels of vitamin D.112 The risk of heart disease can be increased by exposure to various chemicals at home, including arsenic,113 endocrine disruptors and pesticides,114 lead115 and mercury.116 If there are concerns in this area, it is useful to perform tests to measure the levels of such chemicals and heavy metals.

Environment can be conducive or not conducive to a healthy lifestyle. Having access to attractive and safe parks, for example, increases the likelihood of being physically active. Our social environment at work or home, and the advertising we are subject to, all have their effects. For example, employees who experience a ‘just’ work environment had a 35% lower risk of heart disease than employees with low or intermediate level of justice, independent of other lifestyle and risk factors.117 Chronic noise exposure can also be a stressor, and living in a noisy environment increases the risk of heart disease, mostly among those who tend to be annoyed by the noise.118

THE ORNISH PROGRAM FOR HEART DISEASE

Dean Ornish is a US cardiologist who pioneered an integrated approach to cardiac rehabilitation, which serves as an excellent model for holistic care.119 Although it is not based on the ESSENCE model discussed above (and in Ch 6), it includes all the elements in a systematic and cohesive way. The Ornish program was the first demonstration ever that, given the right conditions, cardiovascular disease is a reversible illness. Importantly, the program improved quality of life as well as producing better clinical outcomes.120 In the first landmark study published in The Lancet, people with already well-established heart disease were divided into two groups. The control group had conventional medical management only and the intervention group had the usual medical management plus the Ornish lifestyle program. The program consisted of:

Patients were followed with regard to angina frequency, duration and severity. They also had angiograms before the program and 12 months later, to measure whether their coronary arteries were becoming more or less blocked. The findings are summarised in Table 25.2. Basically, the cardiovascular health of patients in the Ornish program improved significantly.

TABLE 25.2 Summary of the results of the Ornish program on progression of atherosclerosis, and symptom frequency, duration and severity

| Intervention group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Progression | 82% regressed | 53% progressed |

| Symptom: | ||

In both groups, improvement was directly related to lifestyle change in a so-called ‘dose–response’ manner, meaning that the more the person put lifestyle change into effect in their day-to-day life, the greater the improvement in their condition. Another important point is that the program saved a huge amount of money by reducing cardiac events, hospitalisations, medications and the need for invasive procedures.121 The observation that enhancing mental health and coping with stress were great contributors to good outcomes and healthy lifestyle change is not surprising, as we know that poor mental health and high stress are significant predictors of relapse to unhealthy lifestyle.122

Five-year follow-up of Ornish program participants showed that the divergence between the two groups had widened even further.123 The Ornish group continued to reverse their disease angiographically and symptomatically. Furthermore, the usual-care group had had nearly 2½ times as many major cardiac events over the follow-up period.

1 National Heart Foundation of Australia. The shifting burden of cardiovascular disease. Access Economics. 2005.

2 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2004. Heart, stroke and vascular diseases—Australian facts 2004. AIHW Cat. No. CVD 27. Canberra: AIHW and National Heart Foundation of Australia (Cardiovascular Disease Series No. 22). Online. Available: http://www.heartfoundation.com.au.

3 Vogel JHK, Bolling SF, Costello RB, et al. Integrating complementary medicine into cardiovascular medicine. A report of the American College of Cardiology foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:184-221. a p 187.

4 Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99:2192-2217.

5 Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk–benefit prediction guide. Editorial. BMJ. 2000;320:709-710.

6 Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837-1847.

7 Wei ZH, Wang H, Chen XY, et al. Time- and dose-dependent effect of psyllium on serum lipids in mild-to-moderate hypercholesterolemia: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(70):821-827.

8 Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD. How many patients with coronary artery disease are not achieving their risk-factor targets? Experience in Victoria 1996–1998 versus 1999–2000. Med J Aust. 2002;176:211-215.

9 National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Position Statement on Lipid Management; 2005.

10 National Prescribing Service Ltd. Clinical audit. Management of hypertension. New South Wales: NPS Ltd. Online. Available: http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/22837/Hypertension2007ClinicalAuditPack.pdf.

11 Rosenfeldt FL, Hilton D, Pepe S, et al. Systematic review of effect of coenzyme Q10 in physical exercise, hypertension and heart failure. Biofactors. 2003;18:91-100.

12 Stevinson C, Pittler MH, Ernst E. Garlic for treating hypercholesterolemia. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(6):420-429.

13 Pittler MN, Ernst E. Clinical effectiveness of garlic (Allium sativum). Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(11):1382-1385.

14 Reid K. Effect of garlic on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovascular Disord. 2008;16(8):13.

15 Reinhart KM, Coleman CI, Teevan C, et al. Effects of garlic on blood pressure in patiens with and without systolic hypertension: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(12):1766-1771.

16 Antonello M, Montemurro D, Bolognesi M, et al. Prevention of hypertension, cardiovascular damage and endothelial dysfunction with green tea extracts. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(12):1321-1328.

17 Nakachi K, Matsuyama S, Miyake S, et al. Preventive effects of drinking green tea on cancer and cardiovascular disease: epidemiological evidence for multiple targeting prevention. Biofactors. 2000;13(1–4):49-54.

18 Jee SH, Miller ERIII, Guallar E, et al. The effect of magnesium supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15(8):691-696.

19 National Heart Foundation. Guidelines; 2008. Online. Available: http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/Search/Pages/Results.aspx?k=management%20guidelines%20for%20hypertension.

20 Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J. Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Int Med. 1996;156(7):745-752.

21 Cherchi A, Lai C, Angelino F, et al. Effects of L-carnitine on exercise tolerance in chronic stable angina: a multi-center, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled crossover study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1985;23(10):569-572.

22 Overvad K, Diamant B, Holm L, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in health and disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53(10):764-770.

23 Kamikawa T, Kobyashi A, Yamashita T, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 on exercise tolerance in chronic stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56(4):247-251.

24 Rosenfeldt FL, Pepe S, Linnane A, et al. Coenzyme Q10 protects the aging heart against stress: studies in rats, human tissues, and patients. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;959:355-359.

25 Rosenfeldt F, Marasco S, Lyon W, et al. Coenzyme Q10 therapy before cardiac surgery improves mitochondrial function and in vitro contractility of myocardial tissue. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(1):25-32.

26 Rosenfeldt FL, Pepe S, Linnane A, et al. The effects of ageing on the response to cardiac surgery: protective strategies for the ageing myocardium. Biogerontology. 2002;3(1/2):37-40.

27 Rosenfeldt FL, Korchazhkina OV, Richards SM, et al. Aspartate improves recovery of the recently infarcted rat heart after cardioplegic arrest. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14(2):185-190.

28 Munsch CM, Rosenfeldt FL, O’Halloran K, et al. The effect of orotic acid on the response of the recently infarcted rat heart to hypothermic cardioplegia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1991;5(2):82-92.

29 Munsch C, Williams JF, Rosenfeldt FL. The impaired tolerance of the recently infarcted rat heart to cardioplegic arrest: the protective effect of orotic acid. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21(8):751-754.

30 Hadj A, Esmore D, Rowland M, et al. Pre-operative preparation for cardiac surgery utilising a combination of metabolic, physical and mental therapy. Heart Lung Circ. 2006;15(3):172-181.

31 Cutshall SM, Fenske LL, Kelly RF, et al. Creation of a healing enhancement program at an academic medical center. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2007;13(4):217-223.

32 Anderson PG, Cutshall SM. Massage therapy: a comfort intervention for cardiac surgery patients. Clin Nurse Spec. 2007;21(3):161-165.

33 Pepe S, Marasco SF, Haas SJ, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in cardiovascular disease. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Suppl):S154-S167.

34 Rosenfeldt FL, Haas SJ, Krum H, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of hypertension: a meta-analysis of the clinical trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(4):297-306.

35 Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2864-2870.

36 Sali A. Integrative medicine and arrhythmias. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(7):527-528. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/200707/200707sali.pdf.

37 Holubarsch CJF, Colucci WS, Meinertz T, et al. Survival and prognosis: investigation of Crataegus extract WS1442 in congestive heart failure (SPICE)—rationale, study design and study protocol. Eur J Heart Fail. 2000;2(4):431-437. (Results presented at American College of Cardiology meeting March 2007.)

38 Pittler MH, Guo R, Ernst E. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD005312.

39 Singh U, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation and heart failure. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(6/1):286-293.

40 Morisco C, Trimarco B, Condorelli M. Effect of coenzyme Q10 therapy in patients with congestive heart failure: a long-term multicentre randomised study. Clin Investig. 1993;71(8 Suppl):S134-S136.

41 Sinatra ST. Metabolic cardiology: the missing link in cardiovascular disease. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009;15(2):48-50.

42 Stocker R, Pollicino C, Gay P, et al. Neither plasma coenzyme Q10 concentration, nor its decline during pravastatin therapy, is linked to recurrent cardiovascular disease events: a prospective case-control study from the LIPID study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187(1):198-204.

43 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of intermittent claudication: a meta-22 analysis of randomised trials. Am J Med. 2000;108:276-281.

44 Blumenthal M, The American Botanical Council. The ABC clinical guide to herbs. New York: Thieme, 2003;383-385.

45 McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tiller W, et al. The effects of emotions on short-term power spectrum analysis of heart-rate variability. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(14):1089-1093.

46 Strike PC, Perkins-Porras L, Whitehead DL, et al. Triggering of acute coronary syndromes by physical exertion and anger: clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Heart. 2006;92:1035-1040.

47 Everson S, Kaplan G, Goldberg D, et al. Anger expression and incident stroke: prospective evidence from the Kuipio ischaemic heart disease study. Stroke. 1999;30(3):523-528.

48 Weissman M, Markowitz J, Ouellette R, et al. Panic disorder and cardiovascular/cerebrovascular problems: results from a community survey. Am J Psych. 1990;147(11):1504-1508.

49 Simonsick E, Wallace R, Blazer D, et al. Depressive symptomatology and hypertension-associated morbidity and mortality in older adults. Psychosom Med. 1995;57(5):427-435.

50 Appels A, Otten F. Exhaustion as precursor of cardiac death. Br J Clin Psych. 1992;31(3):351-356.

51 Appels A, Kop W, Bar F. Vital exhaustion, extent of atherosclerosis, and the clinical course after successful percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(12):1880-1885.

52 Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence-based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1999;318(7196):1460-1467.

53 Rozanski A, Blumenthal J, Kaplan J. Impact of psychosocial factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99(16):2192-2217.

54 Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. a review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1):51-61.

55 Linden W, Stossel C, Maurice J. Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(7):745-752.

56 Sokejiana S, Kagamimori S. Working hours as a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction in Japan: a case control study. BMJ. 1998;317(7161):775-780.

57 Steptoe A, Kunz-Ebrecht S, Owen N, et al. Socioeconomic status and stress-related biological responses over the working day. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(3):461-470.

58 Steptoe A, Kunz-Ebrecht S, Owen N, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status and job control on plasma fibrinogen responses to acute mental stress. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(1):137-144.

59 Ishizaki M, Martikainen P, Nakagawa H, et al. The relationship between employment grade and plasma fibrinogen level among Japanese male employees. YKKJ Research Group. Atherosclerosis. 2000;151(2):415-421.

60 Wenneberg SR, Schneider RH, Walton KG, et al. A controlled study of the effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on cardiovascular reactivity and ambulatory blood pressure. Int J Neurosci. 1997;89:15-28.

61 Alexander CN, Schneider R, Claybourne M, et al. A trial of stress reduction for hypertension in older African Americans, II: sex and risk factor subgroup analysis. Hypertension. 1996;28:228-237.

62 Castillo-Richmond A, Schneider R, Alexander C, et al. Effects of stress reduction on carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive African Americans. Stroke. 2000;31:568-573.

63 Schneider RH, Alexander CN, Staggers F, et al. Long-term effects of stress reduction on mortality in persons > or = 55 years of age with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(9):1060-1064.

64 Maselko J, Kubzansky L, Kawachi I, et al. Religious service attendance and allostatic load among high-functioning elderly. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(5):464-472.

65 King DE, Mainous AGIII, Steyer TE, et al. The relationship between attendance at religious services and cardiovascular inflammatory markers. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(4):415-425.

66 Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality. Linkages to physical health. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):36-52.

67 Obisesan T, Livingston I, Trulear HD, et al. Frequency of attendance at religious services, cardiovascular disease, metabolic risk factors and dietary intake in Americans: an age-stratified exploratory analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(4):435-448.

68 Berlin J, Colditz G. A meta analysis of physical activity in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:612-628.

69 Shinton R, Sagar G. Lifelong exercise and stroke. BMJ. 1993;307:231-234.

70 Moore S. Physical activity, fitness and atherosclerosis. In: Bouchard C, Shepherd R, Stephens J, editors. Physical activity, fitness and health. Illinois: Human Kinetics; 1994:570-577.

71 Sdringola S, Nakagawa K, Nakagawa Y, et al. Combined intense lifestyle and pharmacologic lipid treatment further reduce coronary events and myocardial perfusion abnormalities compared with usual-care cholesterol-lowering drugs in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:263-272.

72 Eliasson M, Asplund K, Evrin P. Regular leisure time physical activity predicts high levels of tissue plasminogen activator. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:1182-1188.

73 Tsatsoulis A, Fountoulakis S. The protective role of exercise on stress system dysregulation and comorbidities. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1083:196-213.

74 Fagard R, Tipton C. Physical activity, fitness and hypertension. In: Bouchard C, Shepherd R, Stephens J, editors. Physical activity, fitness and health. Illinois: Human Kinetics; 1994:633-655.

75 Kelley G, McClellan P. Antihypertensive effects of aerobic exercise—a brief meta-analytic review. Am J Hypertens. 1994;7:115-119.

76 Hamer M. Exercise and psychobiological processes: implications for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Sports Medicine. 2006;36(10):829-838.

77 Edwards KM, Ziegler MG, Mills PJ. The potential anti-inflammatory benefits of improving physical fitness in hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25(8):1533-1542.

78 American College of Sports Medicine, American Heart Association. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events: placing the risks into perspective. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2007;39(5):886-897.

79 Thompson PD, Franklin BA, Balady GJ, et al. American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology. American College of Sports Medicine. Exercise and acute cardiovascular events placing the risks into perspective: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(17):2358-2368.

80 Tanasescu M, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, et al. Exercise type and intensity in relation to coronary heart disease in men. JAMA. 2002;288:1994-2000.

81 Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:716-725.

82 Owen N, Bauman A. The descriptive epidemiology of physical inactivity in adult Australians. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:305-310.

83 Braith RW, Stewart KJ. Resistance exercise training: its role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2006;113(22):2642-2650.

84 Fleg JL. Exercise therapy for elderly heart failure patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23(1):221-234.

85 Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Cheetham C, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance exercise training improves functional capacity and strength in CHF. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1565-1570.

86 Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Dembo L, et al. Effect of aerobic and resistance exercise training on vascular function in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(4):1999-2005.

87 Chatriwalla AK, Nicholls SJ, Wang TH, et al. Low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood pressure and progression of coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(13):1110-1115.

88 de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin J-L, et al. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction. Final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:779-785.

89 Lipid Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with prevention in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

90 Biesaeski HK. Nutraceuticals, the link between nutrition and medicine. In: Kramer K, Hoppe PP, Packer L, editors. Nutraceuticals in health and disease prevention. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2001:1-26.

91 National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143-3421.

92 Butt MS, Sultan MT, Iqbal J. Garlic: nature’s protection against physiological threats. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009;49(6):538-551.

93 Reinhart KM, Talati R, White CM, et al. The impact of garlic on lipid parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22(1):39-48.

94 van Ee JH. Soy constituents: modes of action in low-density lipoprotein management. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(4):222-234.

95 Chen JT, Wesley R, Shamburek RD, et al. Meta-analysis of natural therapies for hyperlipidemia: plant sterols and stanols versus policosanol. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(2):171-183.

96 Harris WS. N-3 fatty acids and serum lipoproteins: human studies. AJM Clin Nutr. 1917;65:1645S-1654S.

97 Marchioli R, Schweiger C, Tavazzi L, et al. Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione Trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9177):447-455.

98 Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomized open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9567):1090-1098.

99 Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. (American Heart Association Nutrition Committee). Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747-2757.

100 Wang X, Qin X, Demirtas H, et al. Efficacy of folic acid supplementation in stroke population: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1876-1882.

101 Kamanna VS, Kashyap ML. Mechanism of action of niacin on lipoprotein metabolism. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2000;2:36-46.

102 Kris-Etherton PM, Lichtenstein AH, Howard BV, et al. American Heart Association Scientific Statement. Antioxidant vitamin supplements and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2004;110:637-641.

103 Sánchez-Moreno C, Jiménez-Escrig A, Martín A. Stroke: roles of B vitamins, homocysteine and antioxidants. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22(1):49-67.

104 Ebrahim S, Smith GD, McCabe C, et al. Cholesterol and coronary heart disease: screening and treatment. Quality in Health Care. 1998;7:232-239.

105 Bartley M, Fitzpatrick R, Firth D, et al. Social distribution of cardiovascular disease risk factors: change among men in England 1984–1993. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 2000;54(11):806-814.

106 Bosma H, Marmot MG, Hemingway H, et al. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in the Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. BMJ. 1997;314:558-565.

107 Work in America: report of a Special Task Force to the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1973.

108 Berkman L, Syme S. Social networks, host resistance and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186-204.

109 Boden-Albala B, Litwak E, Elkind MS, et al. Social isolation and outcomes post stroke. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1888-1892.

110 Luecken LJ. Childhood attachment and loss experiences affect adult cardiovascular and cortisol function. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:765-772.

111 Cancado JE, Braga A, Pereira LA, et al. Clinical repercussions of exposure to atmospheric pollution. Jornal Brasileiro De Pneumologia: Publicacao Oficial Da Sociedade Brasileira De Pneumologia E Tisilogia. 2006;32(Suppl 2):S5-S11.

112 Holick MF. Vitamin D: importance in the prevention of cancers, type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(3):362-371.

113 Wang CH, Hsiao CK, Chen CL, et al. A review of the epidemiologic literature on the role of environmental arsenic exposure and cardiovascular diseases. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;222(3):315-326.

114 Newbold RR, Padilla-Banks E, Snyder RJ, et al. Developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors and the obesity epidemic. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23(3):290-296.

115 Navas-Acien A, Guallar E, Silbergeld EK, et al. Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease—a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(3):472-482.

116 Virtanen JK, Rissanen TH, Voutilainen S, et al. Mercury as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18(2):75-85.

117 Kivimaki M, Ferrie JE, Brunner E, et al. Justice at work and reduced risk of coronary heart disease among employees: the Whitehall II Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2245-2251.

118 Willich SN, Wegscheider K, Stallmann M, et al. Noise burden and the risk of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:276-282.

119 Ornish D. Dr Dean Ornish’s program for reversing heart disease: the only system scientifically proven to reverse heart disease without drugs or surgery. New York: Random House, 1990.

120 Ornish D, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary heart disease? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet. 1990;336:129-133.

121 News. US insurance company covers lifestyle therapy. BMJ. 1993;307:465.

122 Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Honig A, et al. Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psych. 2001;58(3):221-227.

123 Ornish D, Scherwitz L, Billings J, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001-2007.