10 Cardiology

Syncope

What are the key questions in establishing the diagnosis?

• Reliable eye-witness account: if not available, make a phone call to the patient’s workplace.

• Prodromal symptoms: non-specific but almost always present for some minutes before a vasovagal attack (faint).

• Precipitating cause: anything from the sight of blood to a hangover!

In the absence of any abnormal investigations, the most likely diagnosis is vasovagal syncope (see Table 15.8, Features of fits and faints). You should be aware of some other specific forms of vasovagal syndrome:

• Carotid sinus syncope: on turning head or shaving the chin. Due to carotid sinus hypersensitivity, usually in the elderly.

• Cough syncope: after a paroxysm of coughing, usually in a patient with obstructive airways disease.

• Micturation syncope: more common in men. Usually occurs in the night when going to pass urine or during micturation itself.

What is the differential diagnosis?

There are many other causes of syncope and all might need to be excluded.

• Neurological: seizures, cerebrovascular disease (TIA, CVA or vertebrobasilar ischaemia) are the most common causes. A good eye-witness account is key to the diagnosis. Note: Some jerky movements of the limbs, and even incontinence, can occur in a prolonged vasovagal attack, especially if the patient remains upright.

• Hyperventilation/anxiety (if suspected, symptoms can often be readily reproduced by voluntary hyperventilation): usually associated with a tachycardia. The patient often has symptomatic palpitations and might feel light-headed, a feeling of being distanced from the surroundings, chest pain and/or paraesthesiae with numbness in arms, hands or lips. Pallor and peripheral cyanosis can be striking in a full-blown attack. Circumstances provoking an attack can often be the same as for a faint (e.g. warm room, stressful situation).

• Orthostatic hypotension: especially in elderly patients. This is often caused by drugs, e.g. for hypertension, but don’t forget autonomic neuropathy and Parkinson’s disease.

A cardiac cause of syncope should be sought in all patients with known structural heart disease.

Investigation

This patient required further investigation as the LBBB indicates cardiac disease.

Treatment and progress

A DDD pacing system (see p. 278) was implanted and programmed to produce a tachycardic response to counter any detected bradycardia of sudden onset. So far she has had no more syncopal attacks.

A clinical approach to patients with tachycardia

1. What is the heart rate? – i.e. 180 beats/min in this man

3. Are the ECG complexes broad or narrow?

Having answered these questions, you should decide who needs admission to hospital (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Patients with tachycardia: who to admit to the Medical Assessment Unit?

| Broad complex | Narrow complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Collapsed | Usually need immediate cardioversion and must be admitted from A&E. Do not give verapamil or other negatively inotropic drugs | Usually need admission into hospital, especially if the patient is in heart failure |

| Did not collapse | The most difficult category to sort out | Can probably go home if tachycardia stops on treatment (Case 1) |

| Probably need admission to sort out diagnosis | Need outpatient assessment | |

| Irregular tachycardia in this group may be due to WPW with AF, so do not give verapamil | If this is a recurrent problem they need to be referred to a cardiologist to be considered for EPS, as they may benefit from radiofrequency ablation of their pathway or their arrhythmia focus |

AF, atrial fibrillation; EPS, electrophysiological studies; WPW, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

• Always assume a broad complex tachycardia is VT until proved otherwise.

• If in doubt use DC cardioversion rather than drugs.

• Seek advice if your first drug does not work.

• Beware of verapamil (which should not be used as first-line therapy) and other negatively inotropic drugs.

• Check the electrolytes and correct them appropriately before using drugs, but do not delay treatment in a patient who is compromised because you are waiting for results. Remember in an emergency, K+ levels can be roughly measured using blood gas machines in A&E and used to guide replacement therapy.

The ECG and classification of tachycardias

SVT

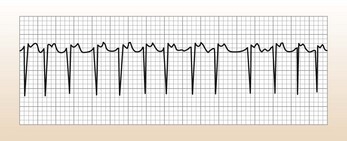

These are narrow complex tachycardias (Fig. 10.1), unless there is bundle branch block. Adenosine is very useful for their diagnosis and will terminate some SVTs:

• Atrial tachycardia: an SVT from a focus in the atrium, rather than due to re-entry.

• Atrial flutter (Afl): look for regular rhythm, often with a rate of 150. Adenosine will help in the diagnosis, often revealing underlying flutter waves.

• Atrial fibrillation (AF): look for lack of P waves, irregular rhythm and baseline; this can be very hard to see with very fast rates, in which case adenosine will help.

Features suggesting that a tachycardia might be an SVT

• Normal LBBB or RBBB morphology but be careful: VT from RV outflow tract with LBBB morphology can look like SVT. A small stubby R wave in V1–2 is characteristic of VT.

• You might be able to see evidence of both atrial and ventricular activity. A constant relationship between the P waves and the QRS complexes suggests a supraventricular origin.

• The frontal and horizontal QRS axes are in the same general direction as that in sinus rhythm.

• It slows with manoeuvres designed to increase vagal tone, e.g. carotid sinus massage.

• If the onset is witnessed you might see a P wave that is premature.

Management

Case history (2)

A 57-year-old woman presents with a tachycardia at a rate of 132 per minute.

On examination she is hypotensive (90/50), looks pale and distressed and has bibasal crackles.

Diagnosis.

This is broad complex tachycardia with gross axis deviation, probably VT (see Table 10.2). She needs urgent treatment ( see below).

Table 10.2 Distinction between supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with bundle branch block and ventricular tachycardia (VT)

Ventricular tachycardia (VT)

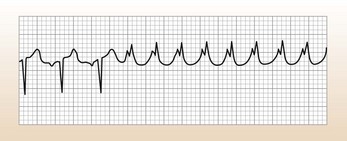

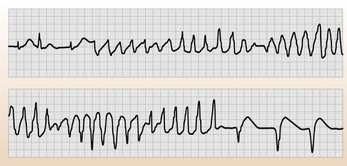

This causes a broad complex regular tachycardia (Fig. 10.2), often called monomorphic VT. However, a broad complex pattern can be caused by any tachycardia if there is a pre-existing abnormality of the conduction system (usually bundle branch block). So, for example, AF with bundle branch block can cause a broad complex tachycardia that is irregular. Although adenosine (see below) can be useful for diagnostic purposes, do not waste time using it if the patient is compromised.

Features suggesting that a tachycardia might be a VT

• A QRS duration of > 140 ms strongly suggests a ventricular origin.

• The frontal and horizontal axes are grossly discordant with that seen in sinus rhythm. Most people are used to looking at the frontal QRS axis in the limb leads. The horizontal axis is estimated by seeing where the predominantly negative QRS complexes become equiphasic as you look across from V1 towards V6. This equiphasic point is called the zone of transition and is usually at V3 or V4. In VT there might be no transition zone or it might be far to the right, or left, of V4.

• QRS morphology: the pattern is not typical of LBBB or RBBB. These are specific appearances that strongly suggest VT, e.g. concordance; seek help if unsure.

• Fusion beats: these are beats where there is simultaneous activation of the ventricles from a focus of arrhythmia and from the atria via the AV node at the same time. These beats will look like a cross between the standard VT complex and the patient’s normal complexes in sinus rhythm.

• Capture beats: occasionally the atria ‘captures’ a normal complex in the midst of a tachycardia.

• You might be able to see evidence of both atrial and ventricular activity. If there is no constant relationship between the P waves and the QRS complexes it suggests a ventricular origin and this is called atrioventricular dissociation.

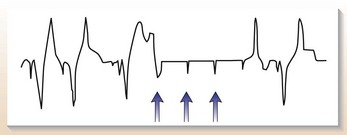

A word about torsade de pointes

Torsade de pointes is an uncommon form of VT with a characteristic ECG pattern (often called polymorphic VT (Fig. 10.3)). The complexes appear to twist around the baseline by virtue of their changes in amplitude. It is particularly associated with syndromes involving a long QT interval. Correct diagnosis of torsade de pointes is necessary because the treatment is very different from VT and treating the underlying cause can often have a marked effect.

The acute treatment of arrhythmias

Remember

Always think about the underlying state of the ventricle when treating an acute arrhythmia.

Problems with the use of any anti-arrhythmic drugs:

• Many arrhythmias arise as a result of pre-existing LV disease. You need to be aware of any drugs that you give which could further suppress LV function and make matters worse.

• A drug that is ineffective for the rhythm in question might also depress ventricular function without alleviating the rate-related stress on the ventricle.

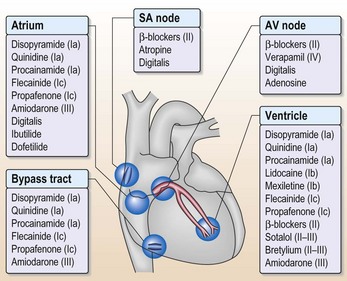

• The final catch when you are treating arrhythmias with drugs (Fig. 10.4) is that ischaemia might alter the electrophysiological activity of drugs. This means that drugs that are anti-arrhythmic under normal circumstances become pro-arrhythmic in ischaemic myocardium.

This limits the use of drugs in many patients because it is often difficult to exclude the possibility of coexisting ischaemia. Because of these problems it is often safer to use DC cardioversion than drugs.

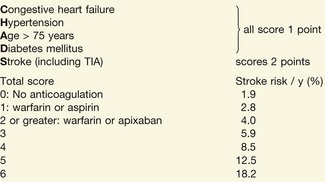

Atrial fibrillation

Should I cardiovert?

Yes, generally DC cardioversion is always worth trying at least once, provided there are no contraindications. Cardioversion can also be achieved with drugs but do not forget there is nearly as much of a risk of a thromboembolic event as with DC cardioversion, so these patients should be appropriately anti-coagulated. Amiodarone (200 mg × 3 daily for 1 week then 200 mg maintenance per day) and class 1c drugs (e.g. flecainide) both promote cardioversion. Figure 10.4 shows the sites of action of drugs on the heart but do not use flecainide in the presence of ventricular disease.

Bradycardia and pacing

• Sinus node: sick sinus syndrome

• AV node: complete heart block, slow atrial fibrillation

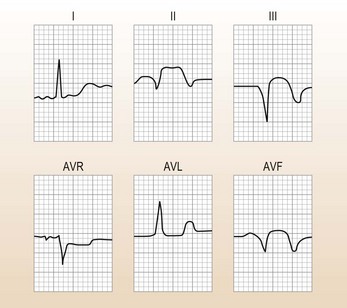

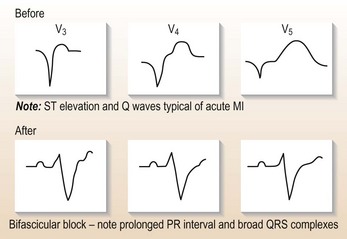

• His–Purkinje system: bifascicular block (left axis deviation and right bundle branch block; RBBB).

Diagnosis

• Difficulties often arise in establishing arrhythmia as a cause of dizzy spells when the condition is intermittent, as it often is in the early stages.

• 24-h ECG is the best investigation but repeat tapes might be needed to demonstrate an abnormality when the history is very suggestive. Occasionally, in a patient with persistent symptoms and no findings on repeat ambulatory ECG monitoring, an implantable ECG recording device can help.

Classification of generic pacemaker code

Notation is by the following abbreviations:

• Chamber paced (0 = none, A = atrial, V = ventricular, D = both or dual).

• Chamber sensed (0 = none, A = atrial, V = ventricular, D = both or dual).

• Response to sensing (0 = none, I = inhibited, T = triggered, D = both T + I).

• Rate response (0 = none, R = rate modulation).

• Anti-tachycardia function (0 = none, P = anti-tachycardia pacing, S = shock, D = pace and shock).

For example: VVI = ventricular pacing, ventricular sensing, inhibition of pacing when beat is sensed; DDD(R) = dual pacing, dual sensing, inhibition and triggered as appropriate when beat is sensed, rate response mode available.

Pacemakers in common use

Rate response (R) is used when a patient has lost the chronotropic response, i.e. cannot increase the heart rate with exercise/stress. The cardiologist inserting the pacemaker will decide this but will need to know the patient’s usual level of activity/independence to make this decision. AAI pacemakers are not often used in practice because a small proportion of these patients go on to develop coexisting AV nodal disease, so in anticipation of this dual-chamber pacemakers are usually implanted.

Pacemaker problems

Technical problems

• Fibrosis occurring around the pacemaker tip: this can cause pacemaker thresholds to rise, which can affect pacemaker function.

• Lead displacement: this will cause pacemaker malfunction, usually manifesting as failure to capture. It is most common in the first 6 weeks after implantation.

• Lead or pacemaker erosion through the skin: usually occurs long term.

• Pacemaker syndrome: vague feelings of weakness or dizziness in patients with VVI pacemakers and complete heart block. This is caused by loss of synchrony between atrial and ventricular contraction leading to episodic falls in BP and retrograde conduction of pacing impulse from ventricle to atria leading to simultaneous atrial and ventricular contraction. It is not seen with dual-chamber pacing and is treated by upgrading to a dual-chamber system.

Case history (2)

A 78-year-old man is admitted for a routine hip replacement. You are fast bleeped to the Orthopaedic ward; when you arrive the orthopaedic SHO tells you the patient is in ‘VT’. You rush to see the patient, who is sitting up reading his newspaper. His rhythm strip from his preoperative ECG is shown (Fig. 10.5). What do you tell the SHO and what do you do?

Remember

• Bradycardia and even transient conduction disturbance (first-degree and Mobitz type I or Wenckebach) can occur in healthy people during sleep. Great caution is needed when interpreting rhythm disturbances at night.

• Always take dizzy spells in a patient with a pacemaker seriously. Formal evaluation and an urgent pacing clinic check are required.

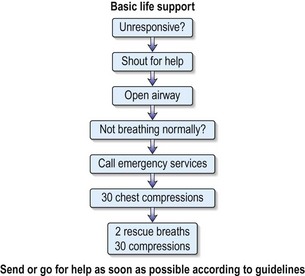

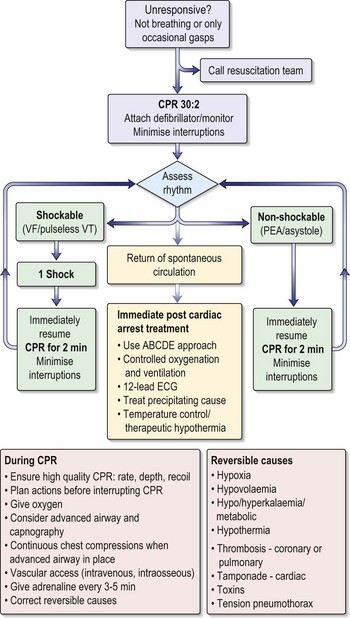

Cardiac arrest and basic life support

What should you do?

An assessment and initial resuscitation of the critically ill patient should be undertaken (ABCDE):

• Airway – remove any obstructing material and make sure airway is clear.

• Breathing – look, listen and feel for signs of breathing.

• Circulation – check carotid and peripheral pulses and start external chest compression if cardiac arrest.

• Disability – conscious level – Glasgow Coma Scale (see Table 15.3, p. 492).

• Examination/exposure. – to allow a full examination to be carried out.

Recent evidence emphasises that maintaining the circulation is the key factor overall.

The order of resuscitation should be CAB, i.e. Circulation, Airways, Breathing.

There are no signs of breathing, you remain alone. What must you do now?

You must leave the patient and go to the nearest telephone to initiate the cardiac arrest call.

You have initiated the emergency call from a telephone further along the corridor.

What should be your next action?

There are no signs of circulation after your assessment. The patient is cyanosed and motionless.

Commence basic life support (see Fig. 10.6).

Chest compressions – carefully note the following:

• Hand position: place the heel of the hand on the sternum, two fingers’ breadth above where the rib margins meet.

• Arm position: lock the elbows and lean directly over the porter.

• Rate: aim to maintain a rate of 100 per minute.

• Depth: compress the chest one-third of the resting diameter of the chest.

• CPR at a ratio of 30 : 2 (30 compressions to 2 breaths), irrespective of number of rescuers.

• Continue this until the defibrillator arrives (Fig. 10.7).

Progress.

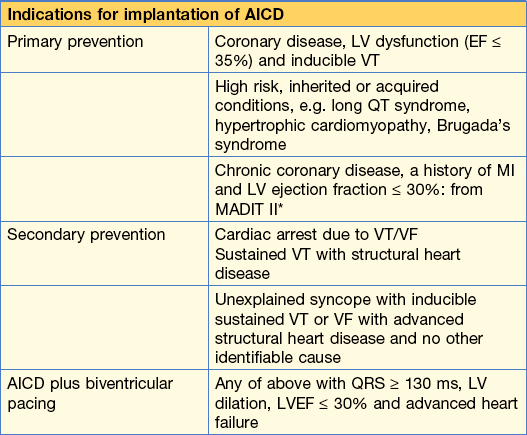

He will need investigations to rule out structural heart disease (echo and angiogram). He will then need electrophysiological studies and an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD; Table 10.3) implanted to prevent recurrence because he has, in effect, had an ‘out of hospital’ VF arrest.

Table 10.3 AICDs – who needs referring for consideration of implantation of one?

* Although this indication is backed up by evidence from the MADIT II trial, the healthcare cost implications are enormous and this is neither a routine indication in the UK at present nor likely to be in the near future.

Chest pain (p. 336) and acute coronary syndromes

Initial assessment

Causes of chest pain to consider

• Aortic dissection (see later)

• Pericarditis: sharp central pain, related to posture and respiration

• Pleurisy: sharp, usually lateral, related to respiration

• Muscular: related to posture, localised tenderness

• Herpes zoster: nerve root distribution, rash might appear later

• Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: retrosternal burning pain but can be very similar to angina.

Note: Many episodes of chest pain do not easily fit into any category and patients are often admitted and treated for acute coronary syndromes. Their symptoms should be assessed in conjunction with their risk factor profile. If in doubt, it is safer to admit.

What features would make you suspect a dissecting aneurysm?

• Pain tends to radiate to back, starts abruptly and is often intense and described as tearing.

• On examination: absent arm or leg pulses, murmur of aortic regurgitation, different BP in arms, neurological signs.

• ECG might be normal or show inferior ischaemia or MI.

• As the dissection in the aortic wall extends proximally, first it disrupts the origin of the subclavian arteries (affecting arm BP), then the carotid arteries (causing neurological sequelae), the origin of the right coronary artery – causing inferior ischaemia – and finally the aortic valve is disrupted causing aortic regurgitation.

If you clinically suspect a dissecting aneurysm you must

• Get a chest X-ray to look for mediastinal widening.

• Never give thrombolytic therapy, heparin or anti-platelet therapy.

• Carefully reduce BP with IV labetolol or sodium nitroprusside.

• Discuss with a cardiothoracic centre.

• CT with contrast or an MRI with contrast: although trans-oesophageal echo (TOE) is an excellent investigation it must be done by a very senior operator and should really be done in the cardiothoracic centre with surgeons on standby.

Immediate medical management in A&E

• IV access should be gained and bloods sent for cardiac markers, biochemistry, lipid profile, FBC and clotting profile.

• Oxygen is no longer recommended in the 2008 British Thoracic Society guidelines, unless the patient is hypoxaemic (check on pulse oximeter).

• Aspirin 300 mg chewed, then 75–150 mg daily, should be given.

• Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 0.3–1 mg should be given for pain relief, repeated as necessary (provided BP is not compromised). This can be followed by an IV infusion of 1–10 mg/hour, which is titrated to pain whilst aiming to keep systolic BP > 100 mmHg.

• IV diamorphine 2.5–5 mg or morphine 10 mg is used as analgesia, with metoclopramide 10 mg as an antiemetic.

• IV β-blockade with metoprolol is given in 5 mg boluses (up to a total of 15 mg), provided the patient is not in cardiogenic shock and/or hypotensive, and that there are no contraindications (e.g. asthma).

• Patients with a STEMI ideally should start β-blockers on the first day, provided they are definitely haemodynamically stable. If there is any doubt, wait until they are stable, to avoid the possibility of cardiac shock developing.

• All ACS patients should be transferred to a coronary care unit (CCU) for continuous monitoring and further specialist care.

• Patients with ACS should have clopidogrel 600 mg loading dose, unless PCI is not being done, in which case the loading dose should be 300 mg; thereafter 75 mg daily is given in addition to aspirin. It has been shown to reduce mortality and the occurrence of major vascular events without an increase in the risk of bleeding in STEMI ACS. Prasugrel 60 mg is an alternative

• N.B. Proton pump inhibitors, particularly omeprazole, reduce the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel because they are inhibitors of cytochrome p450 (CYP2C19), but have only a small therapeutic effect.

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis is still used in some hospitals.

You must know the indications for thrombolysis:

Progress.

This patient fulfils the criteria for PCI but this is not available. She should have thrombolysis, unless there is a contraindication (Table 10.4).

Don’t forget pericarditis!

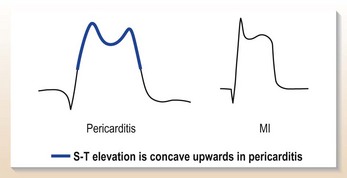

ST changes in pericarditis are often widespread, involving inferior as well as anterior leads (Fig. 10.8) but the ST changes are concave with peaked T waves and there is often associated widespread PR depression (a feature specific to pericarditis).

Also beware

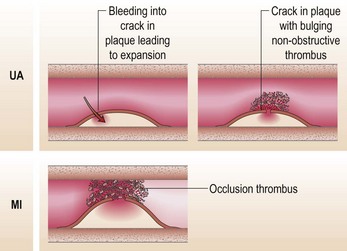

The classification of acute coronary syndromes

The term ‘acute coronary syndrome’ covers the spectrum from unstable angina to MI. This has been a rapidly evolving area (Table 10.5). With this in mind, the decisions to make, using this definition, are:

This helps you direct your therapy; patients with an STEMI should receive PCI or thrombolysis. It is easy to appreciate from the pathogenesis (Fig. 10.10) how failure to treat unstable angina can allow progression to an MI. All the patients should initially be admitted to CCU for management.

Symptoms suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome

• Angina occurring at rest, at night or on minimal effort.

• The pain might require escalating doses of GTN.

• It might be associated with sweating, nausea or breathlessness, especially in an MI.

• There might be a background of worsening exertional symptoms prior to the admission episode of pain.

What do you say and do?

• This patient absolutely cannot go home! He needs admission, treatment for unstable angina and risk stratification. This is exactly the type of patient who, if sent home, will go on to have an MI. Admit him to CCU.

Remember

Management of MI depends on a fast-track approach: ‘time is muscle’.

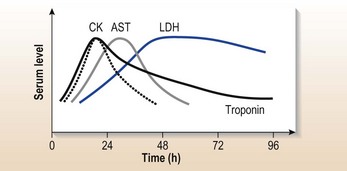

His further management will depend on risk stratification using his troponin (at 24 h), symptoms and ECG. If his symptoms settle:

• If he is troponin positive (high risk) he should be referred for immediate inpatient PCI.

• If he is troponin negative, low risk requiring further investigation, e.g. coronary artery imaging, he can be managed medically initially but will need discussion with the cardiology department.

If his symptoms do not settle:

• He will need urgent inpatient angiography; in the meantime his medical therapy should be increased.

• If he is troponin positive and has dynamic ECG changes he should be started on an IV glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist infusion and referred for angiography that day.

Note: IIb/IIIa antagonist infusions have not been proven to be of benefit as medical therapy alone. A GP IIb/IIIa antagonist, e.g. abiciximab, should be given before PCI and for 12 hours post PCI. If a patient does not go straight away for a PCI, he should receive an infusion of either tirafibam or eptifibatide. The dosing is complex and you need to look it up (e.g. in a National Formulary).

A brief note on glucose and statins

Any patient with an abnormal admission glucose should be started on an IV insulin sliding scale (see p. 424); there is evidence that this improves outcome. High-dose statins (e.g. atorvastatin 80 mg daily) should be started on admission because there is evidence that they improve prognosis above and beyond their lipid-lowering effects, by stabilising the acute plaque.

Acute myocardial ischaemia – who needs acute intervention?

2. Non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI): these patients should be referred for immediate PCI. If PCI is not available, give fondapurinox 2.5 mg sc daily with aspirin 75 mg as they represent a high-risk group for further subsequent events.

3. Unstable angina: patients with ongoing symptoms despite medical treatment with evidence of ischaemia should be discussed with a cardiologist for consideration of PCI.

In the long term, the value of revascularisation – whether by surgery or PCI – in relieving persistent symptoms is beyond doubt. Revascularisation should be considered in all outpatients taking into account their symptoms, lifestyle and investigation results. Generally, bypass surgery is used in: left main stem disease, three-vessel disease, diffuse disease with a poor ventricle and diabetics.

Cardiogenic shock

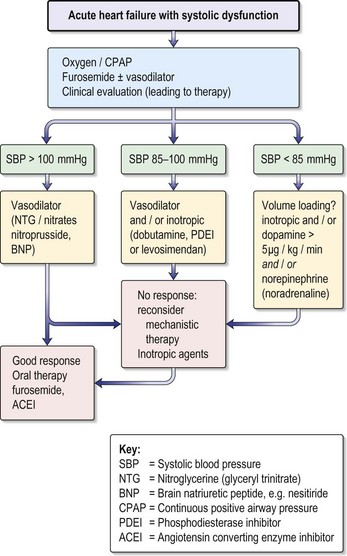

Management (Fig 10.11)

• Get a repeat ECG to look for evidence of reperfusion or continuing ischaemia.

• Check that patient is not volume depleted; this must be done using at least a CVP line and preferably a Swan–Ganz catheter on CCU.

• Check that there is no structural cause: get an urgent transthoracic echo:

• Give inotropes intravenously if there is no response to volume replacement:

• Discuss with cardiologists immediately with a view to transfer for PCI:

• Insert an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), if available: this is a highly effective way of improving cardiac perfusion, and should be used in any patient in whom there is a reasonable prospect of further definitive treatment (e.g. revascularisation/repair VSD). Cannot be used in the presence of significant aortic regurgitation.

Progress.

Remember

• There is never a role for renal dose dopamine in any patient with renal failure

• In patients on prior beta blockers, competitive blockade may persist for 24 h or more and will require much higher doses of dobutamine/dopamine

• It is probably simpler in this situation to use milrinone/enoximone, which bypasses the beta adrenoceptor.

Information

Myocardial stunning and hibernating myocardium

• When heart muscle is subjected to acute ischaemia it might cease to contract but remain viable. This is a potentially reversible cause of haemodynamic problems in acute MI.

• Myocardial stunning. If the blood supply to the relevant area is restored as a result of natural recanalisation of occluded arteries, pharmacological thrombolysis or angioplasty, the functional capacity might return relatively quickly – over a matter of a few hours. Such myocardium is called stunned myocardium.

• Hibernating myocardium. A similar state of affairs might occur on a more chronic basis, usually in severe three-vessel disease. In this case, the cellular ultrastructure might become seriously deranged even though the ischaemic myocytes are still potentially viable. This is known as hibernating myocardium; such myocardium can be restored by revascularisation.

Right ventricular infarction

Case history

A 58-year-old man is admitted with an inferior MI (Fig. 10.12) and is given successful thrombolysis within 2 h of the onset of pain. Although ST elevation and pain largely resolve within 1 h, he remains hypotensive with a systolic BP of 70–80 mmHg associated with a low urine output.

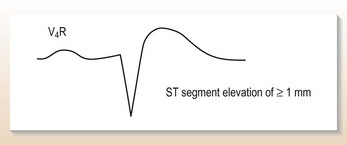

A further ECG with right-sided chest electrodes (Fig. 10.13) suggests right ventricular infarction with ST elevation in V3R–V4R. A fluid challenge of one litre of 5% glucose, given over half an hour IV, restores the BP to 110 systolic with a good urine output.

Right ventricular infarction is:

• Diagnosed readily by elevation of ST segment in V3R–V4R on right-sided ECG

• Associated with volume-dependent hypotension

• Often associated with elevation of JVP without other evidence of heart failure

• Associated with a higher incidence of all post-MI complications, e.g. arrhythmias, cardiac rupture.

Heart failure and cardiogenic shock usually reflect extensive cardiac damage but cardiac ‘stunning’ might be present, and active treatment can save lives.

Heart failure following an MI

Treatment

• IV diamorphine boluses 2.5–10 mg.

• An IV nitrate infusion (0–10 mL/h), titrated to blood pressure and symptoms.

• Boluses of IV furosemide 40–80 mg, although an infusion is better in severe heart failure.

• Invasive monitoring to help to guide therapy.

• IV inotropes if patient remains hypotensive despite the above measures.

Treatment of underlying poor ventricle

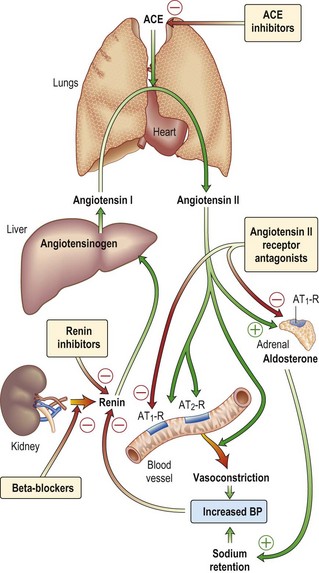

• Introduce ACE inhibitor (or angiotensin receptor antagonist) as soon as possible: ACE inhibitors have been shown to reduce the mortality of this high-risk group by 20–30%. Initiate this therapy as soon as the patient is off inotropes, haemodynamically stable and has stable renal function. Ramipril (1.25 mg initially) is a good choice given its simple dosing regime. A slight deterioration in renal function (up to 30%) might be seen, and if this happens do not increase the dose. If, despite this, renal function continues to worsen, withdraw the ACE inhibitor and reconsider at a later date.

• The introduction of a beta blocker as soon as it is safe: there is a wealth of evidence supporting the use of beta blockers in heart failure to improve prognosis. Evidence from the CAPRICORN and COPERNICUS trials showed that even patients with severe heart failure benefit from the cautious introduction of beta blockers, (provided the patients are not on IV inotropes or vasodilators) e.g. carvedilol, starting at 3.125 mg × 2 daily or bisoprolol, starting at 2.5 mg daily).

• Spironolactone 12.5–25 mg daily (if the heart failure is moderate to severe).

• Consider further revascularisation: remember patients will benefit from revascularisation if part of their poor ventricular function is due to viable stunned or hibernating myocardium. All patients with post-infarct cardiac failure should be seen by a cardiologist.

Post-infarction arrhythmias and heart block

What do you do?

• Reassure the nurse that anti-arrhythmics are not indicated. In the CAST trial, post-MI patients with asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmias were randomised to anti-arrhythmic drugs or placebo; the patients given anti-arrhythmics had a worse outcome.

• There is no role for giving empirical IV Mg2+ to all patients with an acute MI, as shown by the MAGIC trial.

Arrhythmias – atrial and ventricular – are common in the first 24 h after an MI and might be life threatening. For this reason, all these patients must be in monitored beds on CCU. Late arrhythmias (after the first 24 h) are of more prognostic significance and will require specialist evaluation.

Early ventricular arrhythmias

• Ectopics and non-sustained VT are very common, particularly in the 1–2 h after thrombolysis (‘re-perfusion arrhythmias’) and usually require no treatment. Check K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+ and correct if needed.

• Sustained VT or after VF: Standard practice is IV bolus 100 mg over 5 mins, then infusion of 2-4 mg/min) for 24 hrs after cardioversion. Amiodarone is also used.

• Early use of IV beta blockers, e.g. metoprolol, often reduces incidence of ventricular arrhythmias.

Heart block

Information

Indications for temporary pacing post-MI

• Mobitz II heart block with anterior MI.

• Third-degree (complete) heart block (CHB) with inferior MI if hypotensive or cardiac failure, always with anterior MI.

• Bifascicular block (RBBB with left or right axis deviation): usually anterior MI and at risk of CHB.

• Trifascicular block (long PR interval and either LBBB or RBBB with axis deviation): usually anterior MI and at risk of CHB.

• Alternating LBBB and RBBB: usually extensive myocardial injury and high risk of CHB.

Management of late arrhythmias

• Atrial fibrillation/SVT: commonly associated with pericarditis or heart failure. Usually self-limiting or responds to digoxin. Consider cardioversion if this fails or the patient is compromised. Treat pericarditis or cardiac failure actively.

• Ventricular tachycardia: as a late event carries a bad prognosis.

• Beta blockers: all patients should be on these unless contraindicated.

• IV amiodarone: if recurrent VT that has not settled with beta blockers.

• All patients must be referred for early inpatient angiography and appropriate electrophysiological investigations and management as necessary (usually implantation of an internal defibrillator).

• Avoid other anti-arrhythmics, especially those that are negatively inotropic, e.g. flecainide.

Myocardial infarction – secondary prevention

• Strict control of blood pressure

• Diet modification with a view to appropriate weight loss: low fat, low salt, fish oils, high vegetable content

Drug therapy

Antiplatelet therapy

Aspirin

• Contraindications: clear history of type 1 allergic reaction (angio-oedema, anaphylaxis), in which case give clopidogrel 75 mg daily. If there is a history suggestive of peptic ulceration disease, give a proton pump inhibitor. Note: later check for the presence of Helicobacter pylori and eradicate.

Beta blockers

• Should be used in all patients.

• Evidence: 20–25% mortality reduction; greatest benefit in the high-risk group (prior MI, diabetes, transient heart failure). Probably a class effect but documentary evidence for: propranolol, timolol, metoprolol, acebutolol (not atenolol, although this is the most widely used drug in British practice).

Calcium channel blockers

• Non-dihydropyridines: should not be routinely used and in STEMI have not been shown to improve mortality (INTERCEPT trial). However, they can be given in patients in whom beta blockers are contraindicated when rate control is needed.

• Dihydropyridines, e.g. nifedipine: have no place in secondary prevention and might be harmful.

Identifying ‘high-risk’ survivors of MI

• Prior IHD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus

• Heart failure (even transient)

• Late arrhythmias (> 24 h after MI)

• Impaired ventricular function

• Unable to perform exercise tolerance tests (ETT) because of cardiac symptoms.

Remember

• All patients should be offered cardiac rehabilitation

• Strict blood sugar control improves prognosis in diabetics; a 3-month regime of SC insulin is often needed

• After MI, the lipid levels might fall for up to 2 months. Ideally, check the lipid profile at this stage, although statin therapy is given (after a random cholesterol has been sent) at presentation

Heart failure recognition and acute management

Is it heart failure?

• In heart failure the ECG will almost always be abnormal.

• The echo will invariably show depressed systolic function (but beware of a small percentage of patients with diastolic heart failure and normal systolic function).

• The CXR will help as will respiratory function tests (but remember respiratory function tests may be of no help in the acute phase).

• Serum naturietic peptides are useful in the diagnosis of heart failure; serum BNP >200.

Practice point

• Arrhythmia: tachy- or brady- (e.g. atrial fibrillation, complete heart block)

• Excess fluid intake (e.g. post-op IV fluids)

• Excess fluid retention (e.g. NSAIDs, acute kidney injury)

• Anaemia, thyrotoxicosis or any precipitating illness, such as infection in the elderly

• Either precipitating drugs or poor medication compliance in a patient on anti-failure drugs.

Rule out the above with the appropriate investigations and correct them if possible.

Management

The acute phase of therapy consists of:

• IV nitrates (e.g. glyceryl trinitrate 10–200 µg/min titrated to reduce systolic BP by 10–15% and not below 90 mmHg): these provide excellent rapid symptomatic relief by offloading the ventricle, and should be first-line therapy. Continue IV diuretics, initially boluses (e.g. furosemide 40 mg) but he might need a furosemide infusion.

• IV diamorphine (5 mg slowly): this not only relieves symptoms, by offloading the ventricle, but is an excellent anxiolytic.

• ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor antagonist:

• Spironolactone: 12.5–25 mg daily should be given to all patients with moderate to severe heart failure (RALES trial); check the potassium because of risk of hyperkalaemia.

• Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIV): patients often respond very well to just CPAP alone, but might need BIPAP. You should be aware that positive pressure ventilation might cause hypotension: monitor the patient appropriately.

Other lifestyle changes

His breathlessness and pulmonary oedema resolved after 2 days and plans were made to discharge him when his condition was stable.

Selected points

• Heart failure may be difficult to diagnose – especially with diastolic dysfunction.

• A proportion of elderly patients are on diuretics but have no objective evidence of heart failure (systolic or diastolic).

• Echocardiography should be performed in all patients to identify an aetiology.

• ACEIs should be given to all patients unless contraindicated (i.e. renal impairment, aortic stenosis, renal artery stenosis).

Information

• Systolic heart failure is associated with a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction. The heart is enlarged and there is frequently accompanying diastolic heart failure. The cause is often IHD.

• In diastolic heart failure there is normal left ventricular systolic function with a small heart and impaired left ventricular filling. It often occurs in the elderly associated with hypertension. At present there are no data from large trials on treatment of diastolic failure but the expert consensus opinion at present is that it should be treated in the same way as systolic failure.

Valvular heart disease

Aortic stenosis

How should you manage him?

• You must admit him to MDU; you need to quantify the severity of his aortic stenosis with an echocardiogram.

• Patients with severe aortic stenosis have a very high 1-year mortality.

• If he has severe aortic stenosis he should be referred for consideration of aortic valve replacement as an inpatient.

Practice points

• Post-exercise syncope in someone with a systolic murmur is suggestive of significant aortic stenosis.

• A diagnosis of aortic sclerosis should not be made without full echo assessment.

• Soft heart sounds in the context of an aortic murmur often suggest significant stenosis.

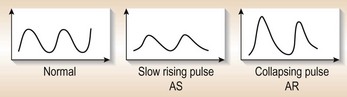

• Although the pulse might be useful in diagnosing aortic valve lesions (Fig. 10.15), you should note that in elderly patients the pulse might not be reduced because of loss of arterial tree elasticity.

• Severe aortic stenosis with symptoms needs referral for inpatient surgery.

• Elective aortic valve replacement of aortic stenosis is associated with a very low mortality and is excellent curative surgery for symptomatic aortic stenosis with good ventricular function.

Aortic regurgitation (AR)

Practice points

• Echocardiography to quantify the severity and left ventricular size and monitor these parameters on a regular basis thereafter.

• When the ventricle begins to dilate, referral for consideration of surgery is necessary.

• Medical therapy with an ACE inhibitor may delay the time until surgery is needed.

When should you consider surgery in valvular disease?

• Aortic stenosis: this is usually well compensated but deterioration is rapid once symptoms have developed. Refer for operation if dyspnoea, chest pain or syncope. Note: as an inpatient if stenosis is severe.

• Aortic regurgitation: refer for operation when LV starts to dilate (end systolic dimension > 5.5 cm).

• Mitral stenosis: refer for opinion when symptoms uncontrolled on medical treatment. Remember percutaneous valvuloplasty may be a first-line option. Generally when the valve area < 1 cm2 then intervention is needed.

• Mitral regurgitation: progressive symptoms despite medical therapy and/or LV dilatation.

Prosthetic valve problems (all these should be referred to a cardiologist urgently)

• Heart failure: must be assumed to be due to valve malfunction until proved otherwise.

• Murmurs: paraprosthetic leaks common but should be formally assessed by urgent echo followed by TOE.

• Infection: blood cultures must be taken for any febrile illness before giving antibiotics. Endocarditis of prosthetic valve should be referred to cardiothoracic centre.

• Anti-coagulants: control is essential (INR 3.5). Always take specialist advice before any surgical intervention. Do not stop a patient’s warfarin or reduce the dose until he/she is fully anti-coagulated with IV heparin.

Infective endocarditis

• Make medical treatment more prolonged

• Promote the need for surgery which might have been avoided had treatment been started earlier.

It follows that endocarditis is a diagnosis that needs to be kept in mind when dealing with any pyrexial or constitutional illness in patients with valvular or congenital heart disease.

Diagnosis is made using the modified Duke criteria (Table 10.6).

Table 10.6 Modified Duke criteria for endocarditis*

← A positive blood culture for infective endocarditis, as defined by the recovery of a typical microorganism from two separate blood cultures in the absence of a primary focus (viridans streptococci, Abiotrophia species, and Granulicatella species; Streptococcus bovis, HACEK† group, or community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus or enterococcus species); or

← Persistently positive blood cultures, defined as the recovery of a microorganism consistent with endocarditis from either blood samples obtained more than 12 hours apart or all three or a majority of four or more separate blood samples, with the first and last obtained at least 1 hour apart; or

← A positive serologic test for Q fever, with an immunofluorescence assay showing phase 1 IgG antibodies at a titre >1 : 800; or

← Predisposition: predisposing heart condition or intravenous drug use

← Fever: temperature ≥ 38°C (100.4°F)

← Vascular phenomena: major arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts, mycotic aneurysm, intracranial haemorrhage, conjunctival haemorrhages, Janeway’s lesion

← Immunologic phenomena: glomerulonephritis, Osler’s nodes, Roth’s spots, rheumatoid factor

← Microbiological evidence: a positive blood culture but not meeting a major criterion as noted above, or serological evidence of an active infection with an organism that can cause infective endocarditis‡

← Echocardiogram: Findings consistent with infective endocarditis but not meeting a major criterion as noted above.

*The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is definite when: (a) a microorganism is demonstrated by culture of a specimen from a vegetation, an embolism, or an intracardiac abscess; (b) active endocarditis is confirmed by histological examination of the vegetation or intracardiac abscess; (c) two major clinical criteria, one major and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria are met.

†HACEK denotes haemophilus species, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella kingae.

‡Excluded from this criterion is a single positive blood culture for coagulase-negative staphylococci or other organisms that do not cause endocarditis. Serologic tests for organisms that cause endocarditis include tests for Brucella, Coxiella burnetii, Chlamydia, Legionella, and Bartonella species.

After Raoult D, Abbara S, Jassal DS, Kradin RL. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 5-2007. A 53-year-old man with a prosthetic aortic valve and recent onset of fatigue, dyspnea, weight loss, and sweats. NEJM 2007.

What do you do and what else do you want to ask the patient?

• If you have good clinical grounds for a diagnosis of endocarditis you must start empirical treatment, as soon as you have taken at least three sets of cultures (from different sites). You take blood for a full blood count and a further blood culture now so that he can have his first dose of antibiotics without delay.

• You will ask him if he has had any recent dental work, if he is an IV drug user or if he has ever been told he has a murmur (pre-existing lesion).

• You will send off baseline U&Es, CRP, ESR, urinalysis and microscopy and get an ECG.

While taking the cultures you ask him a few questions and he tells you someone mentioned he had a murmur when he was a child but nothing further was done. He also tells you he had root canal work 8 weeks ago. You start him on a slow injection of benzylpenicillin (1.2 g, to be given 4-hourly thereafter) and gentamicin (80 mg 12-hourly) for the first 2 weeks. You must subsequently discuss anti-microbial therapy with a microbiologist.

A few practical points

• Prosthetic valve endocarditis is very difficult to manage and must be referred to a cardiothoracic surgical centre.

• Haemodynamic deterioration might precipitate the need for surgery in endocarditis. The difficulty is that operative results are clearly better if the surgeons can wait to allow adequate antibiotic therapy to enable them to operate in a field that is no longer infected. However, in some cases this might not be possible because fatal haemodynamic deterioration can only be prevented by early surgery.

• Endocarditis often needs surgical intervention. Always involve the cardiologists as soon as possible.

• Transthoracic echocardiography does not always exclude a diagnosis of endocarditis and TOE will often help; the cardiologist will give appropriate advice.

• Development of first-degree AV block strongly suggests an aortic root abscess, hence the need for regular ECGs in all cases.

• A fever as a result of antibiotic sensitivity can develop after a prolonged course of intravenous antibiotics (especially penicillins). This can lead to a false suspicion that the endocarditis is not successfully treated: always liaise closely with the microbiologist.

• Always discuss cases that are either not responding or worsening with the surgeons, via the cardiologist.

• Right-sided endocarditis is a disease characteristic of intravenous drug users. The condition presents with cardiac signs such as a murmur or evidence of tricuspid regurgitation on the JVP. However, there might be few signs at the outset and the major abnormality could be on the chest X-ray, with areas of apparent consolidation suggestive of a bronchopneumonia. The condition can present with a ‘white-out’ of the two lung fields.

Pulmonary hypertension

Case history (1)

On examination of her chest she had generalised wheezing with bilateral basal crackles.

What is the prognosis?

Investigations

cor pulmonale

• Chest X-ray: showing large pulmonary arteries ± evidence of underlying lung disease

• ECG: showing right ventricular strain pattern with right axis deviation and often P-pulmonale

• Echo: showing large right ventricle and atrium, tricuspid regurgitation and high PA pressures

• CT chest with contrast: to further delineate underlying lung disease and pulmonary vasculature

Cardiomyopathies

He has a dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

Treatment is as for acute heart failure (p. 304). He recovers well and is able to get back to normal after 4 months.

Some tips on the management of dilated cardiomyopathies (DCMs)

• In principle, the treatment is the same as treatment of heart failure but you should get cardiology input early for advice on specialist investigations and further treatment.

• Define an aetiology if possible, as this might identify a reversible/treatable cause, e.g. alcohol excess:

• It is possible to make a complete recovery from a dilated cardiomyopathy, especially those of viral aetiology (remember to check viral titres).

• Some acute DCMs run an aggressive course with rapidly worsening ventricular function, and cardiac transplantation might be required. Surgically implanted left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are becoming increasingly common as a bridge to either recovery or transplantation.

Case history (2)

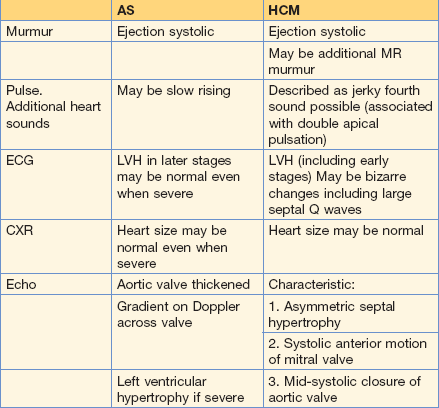

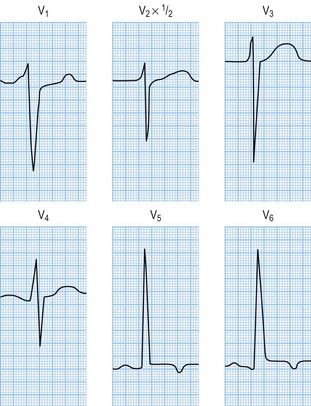

You are a junior doctor in clinic and you see a new GP urgent referral. She is a 35-year-old woman who presented to the A&E department with syncope and palpitations. She was noted to have a soft systolic murmur. She was sent home by A&E as her palpitations had settled and her ECG was thought to be normal. The GP has asked you to see her because she is concerned as the patient’s sister, age 28, dropped dead whilst ironing. Her ECG shows left ventricular hypertrophy with an S in V1 of 21 mm plus an R wave in V6 of > 35 mm (see Figure 10.17).

Some practice points for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

• On echo (which all patients must have) cardinal features include: asymmetrical septal hypertrophy, systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve and an outflow gradient.

• The degree of outflow obstruction and hypertrophy do not reliably correlate with risk of sudden death.

• Screening of family members and referral to a geneticist are essential because certain HCM mutations are associated with a higher risk of sudden death. Don’t forget, HCM can be sporadic as well as hereditary.

• Beta blockers are the mainstay of medical therapy but amiodarone can be useful. However, certain patients will benefit from an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD).

• Patients with outflow obstruction might benefit from septal reduction by either percutaneous alcohol ablation or surgical myomectomy.

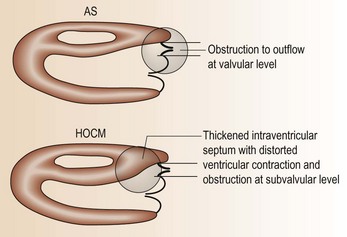

• Sometimes, differentiation of HCM from aortic stenosis can be difficult (Fig. 10.16; Table 10.7) – get specialist advice!

Hypertension (HT)

How will you assess her?

First you need to decide on the significance of the BP reading:

• Relevance of anxiety: a raised BP is a common response to stress, more so in some individuals than in others. 24-h ambulatory BP monitors can be of help in these situations.

• Prior history of high BP: adds significance to the present reading.

• Presence of family history of hypertension (HT): probably the single most useful determinant in essential HT.

• Relationship to migraine: no direct link between this and HT has been established.

• Relationship to age: BP does rise with age, but still carries an adverse cardiovascular risk. The WHO International Society of Hypertension classify hypertension as a systolic of > 130 mmHg and a diastolic of > 85 mmHg

• Relationship to lifestyle: high alcohol intake, obesity and lack of exercise are common contributory factors in patients with high BP.

What should you be looking for?

• Clinical signs of end organ damage:

Investigations in this group include:

• Renal ultrasound: non-invasive, readily available, excludes major renal pathology.

• Isotope renogram (+ captopril stress): reasonable screening test for renal artery stenosis but not very sensitive (might miss some).

• Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) with contrast will give a definitive diagnosis in renal artery stenosis. Although renal angiography is the gold standard this tends to be used only when intervention (renal angioplasty) is considered.

• 24-h urine collection: catecholamines and cortisol: these require separate bottles! Plasma catecholamines are most accurate for phaeochromocytoma, if available.

• CT/MRI abdomen: when adrenal disease suspected/confirmed + CT, MRI angiography for reno-vascular disease.

What is your immediate management?

• CNS: orientation, focal neurological signs (differentiation of hypertensive encephalopathy and a small stroke might be difficult).

• Fundi: haemorrhages/exudates and/or papilloedema indicate accelerated hypertension.

• LVH: clinical and ECG. Most patients with severe HT have ECG evidence of LVH.

• Urinalysis to look for renal disease and diabetes.

• Remember to look for secondary causes and treat as appropriate.

What drugs are available for treatment in this case?

• Intravenous treatment (labetalol, nitroprusside) should be reserved for a real emergency, e.g. aortic dissection, when minute-to-minute control is needed. But lower BP cautiously.

• In this man, a reasonable approach would be 10 mg capsule of nifedipine intrabuccally, which will gradually reduce his BP over the next half an hour or so.

The swollen/painful leg

Common causes of a swollen leg include:

• Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

• Acute rupture knee joint/Baker’s cyst

Many hospitals now have an excellent DVT service run by specialist nurses.

Investigation of DVT

• B mode venous compression ultrasound: is generally the first-line investigation of choice. It detects clot reliably only in popliteal/femoral vein, not in calf veins. However, 30% of patients with calf vein clots will have an extension and anti-coagulation is now recommended.

• Venography: although probably the gold standard, can be misleading if past history of venous thrombosis and is no longer used as first-line investigation.

Treatment

• 6 months: proximal DVT ± pulmonary embolus

• 3 months: localised calf DVT (6 weeks is probably enough for a first DVT with no persisting risk factors).

Target INR is 2.5. With recurrent DVT, screening for thrombophilia is necessary.

Some practical points

• AF (even when paroxysmal) is the most common cause of embolisation but do not forget rare causes such as endocarditis, ventricular thrombosis and atrial myxoma.

• If you suspect a peripheral embolus involve the vascular surgeon early as minimising time to embolectomy is as vital as ‘door to needle’ time in an MI.

• In the patient with acute abdominal pain and AF, whom the surgeons say is not ‘surgical’, do not forget mesenteric ischaemia.