Chapter 37

Cardiac Pacemakers and Resynchronization Therapy

1. What are the components of a pacing system?

2. What is the accepted pacing nomenclature for the different pacing modalities?

Letter 1: chamber that is paced (A = atria, V = ventricles, D = dual chamber)

Letter 1: chamber that is paced (A = atria, V = ventricles, D = dual chamber)

Letter 2: chamber that is sensed (A = atria, V = ventricles, D = dual chamber, 0 = none)

Letter 2: chamber that is sensed (A = atria, V = ventricles, D = dual chamber, 0 = none)

Letter 3: response to a sensed event (I = pacing inhibited, T = pacing triggered, D = dual, 0 = none)

Letter 3: response to a sensed event (I = pacing inhibited, T = pacing triggered, D = dual, 0 = none)

Letter 4: rate-responsive features (an activity sensor), for example, an accelerometer in the pulse generator that detects bodily movement and increases the pacing rate according to a programmable algorithm (R = rate-responsive pacemaker)

Letter 4: rate-responsive features (an activity sensor), for example, an accelerometer in the pulse generator that detects bodily movement and increases the pacing rate according to a programmable algorithm (R = rate-responsive pacemaker)

3. What is the most important clinical feature that establishes the need for cardiac pacing?

4. What are the three types of acquired AV block?

Second-degree block is divided into two types. Mobitz type I (Wenckebach) exhibits progressive prolongation of the PR interval before an atrial impulse fails to stimulate the ventricle. Anatomically, this form of block occurs above the bundle of His in the AV node. Type II exhibits no prolongation of the PR interval before a dropped beat and anatomically occurs at the level of the bundle of His. This rhythm may be associated with a wide QRS complex.

5. What is the anatomic location of bifascicular or trifascicular block?

Complete block and symptomatic bradycardia

Complete block and symptomatic bradycardia

Alternating bundle branch block

Alternating bundle branch block

Intermittent type II second-degree block with or without related symptoms

Intermittent type II second-degree block with or without related symptoms

Symptoms suggestive of bradycardia and an HV interval greater than 100 ms on invasive electrophysiology study

Symptoms suggestive of bradycardia and an HV interval greater than 100 ms on invasive electrophysiology study

6. When is pacing indicated for asymptomatic bradycardia?

There are few indications for pacing in patients with bradycardia who are truly asymptomatic:

Third-degree AV block with documented asystole lasting 3 or more seconds (in sinus rhythm) or escape rates below 40 beats/min in patients while awake

Third-degree AV block with documented asystole lasting 3 or more seconds (in sinus rhythm) or escape rates below 40 beats/min in patients while awake

Third-degree AV block or second-degree AV Mobitz type II block in patients with chronic bifascicular and trifascicular block

Third-degree AV block or second-degree AV Mobitz type II block in patients with chronic bifascicular and trifascicular block

Congenital third-degree AV block with a wide QRS escape rhythm, ventricular dysfunction, or bradycardia markedly inappropriate for age

Congenital third-degree AV block with a wide QRS escape rhythm, ventricular dysfunction, or bradycardia markedly inappropriate for age

Potential (class II) indications for pacing in asymptomatic patients include the following:

Third-degree AV block with faster escape rates in patients who are awake

Third-degree AV block with faster escape rates in patients who are awake

Second-degree AV Mobitz type II block in patients without bifascicular or trifascicular block

Second-degree AV Mobitz type II block in patients without bifascicular or trifascicular block

The finding on electrophysiologic study of block below or within the bundle of His or an HV interval of 100 ms or longer

The finding on electrophysiologic study of block below or within the bundle of His or an HV interval of 100 ms or longer

When bradycardia, even if extreme, is present only during sleep, pacing is not indicated.

7. What is sick sinus syndrome?

Sinus node dysfunction (SND), also referred to as sick sinus syndrome, is a common cause of bradycardia. Its prevalence has been estimated to be as high as 1 in 600 patients over the age of 65 years, and the syndrome accounts for approximately 50% of pacemaker implantations in the United States. SND may be due to replacement of nodal tissue with fibrous tissue at the sinus node itself, or it may be due to extrinsic causes (e.g., drugs, electrolyte imbalance, hypothermia, hypothyroidism, increased intracranial pressure, or excessive vagal tone). Abnormal automaticity and conduction in the atrium predispose patients to atrial fibrillation and flutter, and the bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome is a common manifestation of sinus node dysfunction. Therapy to control the ventricular rate during tachycardia by blocking AV conduction with β-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, or digitalis may not be possible, because it may further depress the sinus node. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for SND with documented symptomatic bradycardia, including frequent sinus pauses that produce symptoms. It is also indicated for symptomatic chronotropic incompetence and for symptomatic sinus bradycardia that results from required drug therapy for medical conditions (e.g., rate control for atrial tachyarrhythmias, chronic stable angina, or systolic heart failure).

8. Is pacing indicated for neurocardiogenic syncope?

9. What are the indications for pacing after myocardial infarction (MI)?

Complete third-degree block or advanced second-degree block that is associated with block in the His-Purkinje system (wide-complex ventricular rhythm)

Complete third-degree block or advanced second-degree block that is associated with block in the His-Purkinje system (wide-complex ventricular rhythm)

Transient advanced (second- or third-degree) AV block with a new bundle branch block.

Transient advanced (second- or third-degree) AV block with a new bundle branch block.

Pacing in the setting of an acute MI may be temporary rather than long-term or permanent.

10. What are potential complications associated with pacemaker implantation?

11. What is pacemaker syndrome?

12. What is twiddler’s syndrome?

13. What is pacemaker-mediated tachycardia?

Pacemaker-mediated tachycardia (PMT) is a form of reentrant tachycardia that can occur in patients who have a dual-chamber pacemaker. If the AV node retrogradely conducts a ventricular-paced beat or a premature ventricular contraction (PVC) back to the atrium and depolarizes the atrium before the next atrial-paced beat, this atrial activation will be sensed by the pacemaker atrial lead and interpreted as an intrinsic atrial depolarization. Consecutively, the pacemaker will then pace the ventricle after the programmed AV delay and perpetuate the cycle of ventricular pacing → retrograde ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction → atrial sensing → ventricular pacing (the pacemaker forms the antegrade limb of the circuit, and the AV node is the retrograde limb). Consider PMT in patients with a dual-chamber pacemaker who experience palpitations, rapid heart rates, lightheadedness, syncope, or chest discomfort. It is corrected by programming the pacemaker with a postventricular atrial refractory period (PVARP) so that atrial events occurring shortly after ventricular events are ignored by the pacemaker.

14. What is cardiac resynchronization therapy?

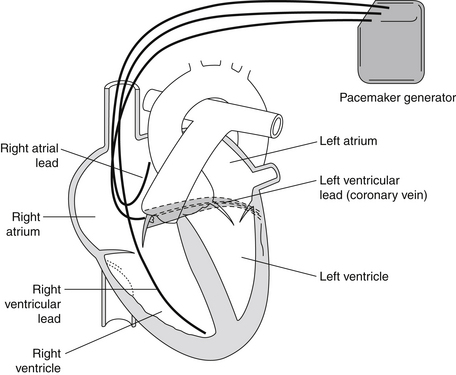

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) refers to simultaneous pacing of both ventricles (biventricular [Bi-V] pacing). The rationale for CRT is based on the observation that the presence of a bundle branch block or other intraventricular conduction delay can worsen systolic heart failure by causing ventricular dyssynchrony, thereby reducing the efficiency of contraction. Pacing of the left ventricle (LV) is achieved either by placing a transvenous lead in the lateral venous system of the heart through the coronary sinus (preferred approach; Fig. 37-1) or by placement of an epicardial LV lead (requires a limited thoracotomy and general anesthesia). The rationale for CRT is that ventricular dyssynchrony can further impair the pump function of a failing ventricle. Potential mechanisms of benefit include improved contractile function (improvement in ejection fraction [EF], increase in cardiac index and blood pressure, decrease in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) and reverse ventricular remodeling (reductions in LV end-systolic and end-diastolic dimensions, severity of mitral regurgitation, and LV mass).

Figure 37-1 Biventricular (Bi-V) pacemaker. Note the pacemaker lead in the coronary sinus vein that allows pacing of the left ventricle simultaneously with the right ventricle. Bi-V pacing is used in selected patients with congestive heart failure with left ventricular conduction delays to help resynchronize cardiac activation and thereby improve cardiac function. (From Goldberger AL: Clinical electrocardiography: a simplified approach, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2006, Mosby.)

CRT is indicated in patients with advanced heart failure (usually New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III or IV), severe systolic dysfunction (LV ejection fraction 35% or less), and intraventricular conduction delay (QRS more than 120 ms), who are in sinus rhythm and have been on optimal medical therapy. CRT can be achieved with a device designed only for pacing or can be combined with a defibrillator (many patients who are candidates for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [ICD] are also candidates for CRT). CRT has been shown not only to improve quality of life and decrease heart failure symptoms (improvement in NYHA class by one class or increased 6-minute walk distance) but also to reduce mortality and improve survival.

16. Do all patients with dyssynchrony respond to CRT?

17. What are some additional benefits seen in responders to CRT?

18. Is a CRT defibrillator (CRT-D) useful in minimally symptomatic patients with heart failure?

19. Can ventricular pacing be deleterious?

20. Can CRT help patients with CHF and narrow QRS?

Initial single-center, nonrandomized case series reported improvement in LV function in patients with CHF and narrow QRS who received CRT. The theory was that the QRS duration on ECG may not accurately detect electrical dyssynchrony that may benefit from CRT. This theory was primarily driven by the perception of ventricular dyssynchrony as measured by echocardiographic tissue velocity parameters. The Resynchronization Therapy in Normal QRS (RethinQ) trial randomized patients with NYHA class III symptoms, EF less than 35%, narrow QRS (<130 ms), and echocardiographic evidence of dyssynchrony, to receive an ICD alone or CRT-D. There was no significant difference in the primary endpoint of improvement in peak oxygen consumption at 6 months. At this time, there is no conclusive evidence to support the use of CRT in patients with a narrow QRS duration of less than 120 ms.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Abraham, W.T., Fisher, W.G., Smith, A.L., et al. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 346. 2002:1845–1853.

2. Beshai, J.F., Grimm, R.A., Nagueh, S.F., et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy in heart failure with narrow QRS complexes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2461–2471.

3. Bristow, M.R., Saxon, L.A., Boehmer, J., et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 350. 2004:2140–2150.

4. Ellenbogen, K.A., Wilkoff, B.L., Kay, G.N., et al. Clinical cardiac pacing, defibrillation and resynchronization therapy, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

5. Epstein, A.E., DiMarco, J.P., Ellenbogen, K.A., et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2085–2105.

6. Jarcho, J.A. Resynchronizing ventricular contraction in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1594–1597.

7. Linde, C., Abraham, W.T., Gold, M.R., et al. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients and in asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1834–1843.

8. Moss, A.J., Hall, W.J., Cannom, D.S., et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329–1338.