Chapter 5 Cardiac masses, pericardial disease and myocarditis

Cardiac masses

The general protocol for interrogation and subsequent reporting of masses is:

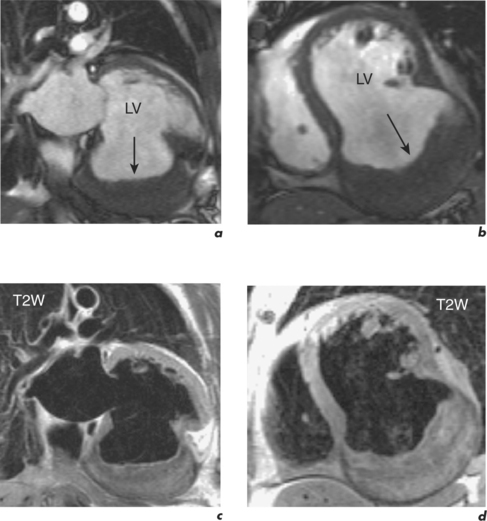

Thrombus

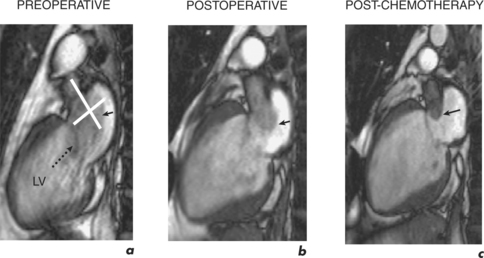

This is by far the commonest cardiac filling defect and both atrial and ventricular thrombi are readily visualized by SE, GE and following gadolinium (Figure 5.1). On T1W SE imaging, thrombus has intermediate signal intensity often slightly higher than myocardium and blood. T2W SE shows surrounding slow-flowing blood as having higher signal intensity than the thrombus itself, thereby enhancing differentiation from myocardium. With SSFP cine GE and velocity mapping techniques thrombus has the lowest signal intensity in distinction to blood flow, even where it is diminished, which has a high signal intensity. Injection of gadolinium contrast agent increases diagnostic accuracy and characteristically demonstrates an avascular filling defect by rest perfusion CMR and EGE. In the case of LV thrombus, subsequent LGE images usually reveal an area of infarction which has acted as the substrate for thrombus formation. For atrial thrombi, a dilated LA and LA appendage can be demonstrated as with transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE).

Tumours

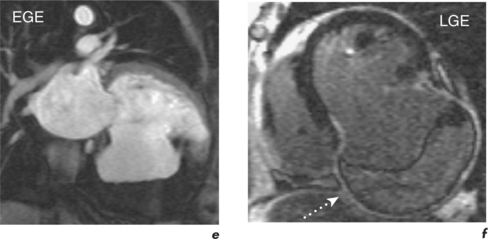

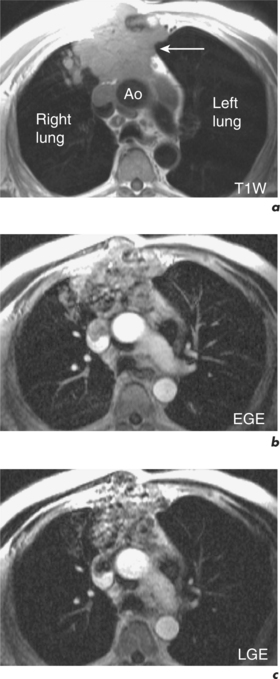

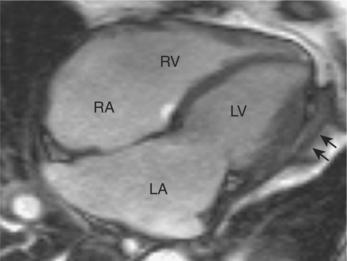

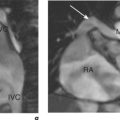

Secondary cardiac deposits are more frequent than primary cardiac tumours, but both are rare with a necropsy incidence of 1% and 0.05% respectively. Secondary involvement is usually clinically silent and limited to the epicardium. Presenting cardiac signs, when they occur, are those of a large pericardial effusion or incipient tamponade, arrhythmias, cardiomegaly or heart failure. Locally infiltrating malignancies include carcinoma of the lung or breast and renal cell carcinoma may embolize to the RA (Figure 5.2). Cardiac metastases are seen with malignant melanomas, leukaemias and lymphomas.

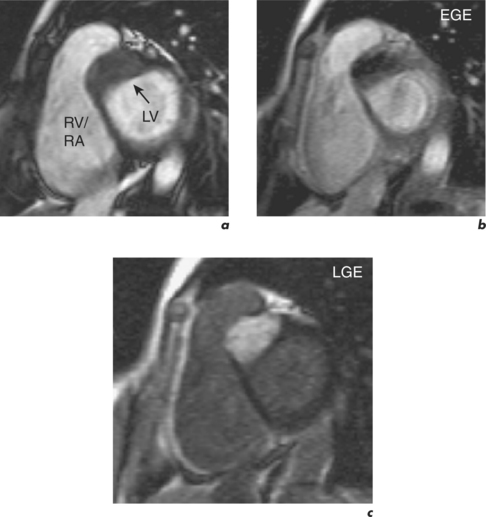

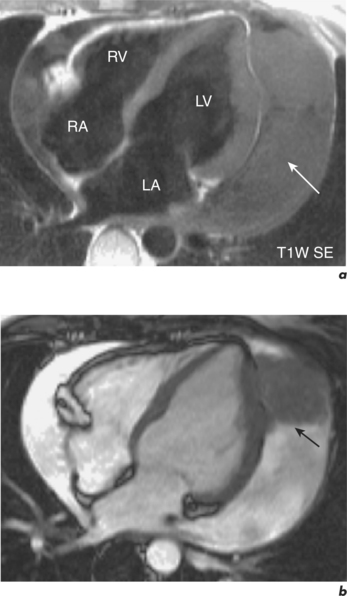

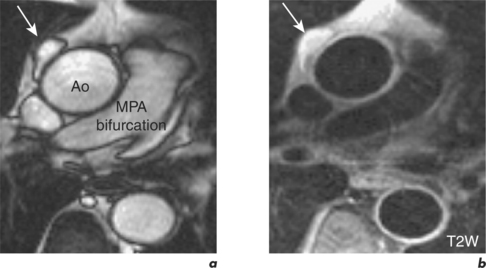

The majority of primary cardiac tumours are benign with the most frequent being atrial myxomas (45%) and cardiac lipomas (20%) (Figure 5.3). Malignant cardiac tumours make up one quarter of primary tumours and the most common are sarcomas (95%). CMR anatomical evaluation of intra- and extracardiac involvement has implications for staging, surgical treatment and surveillance (Figure 5.4). CMR differentiation between malignant and benign tumours uses a combination of general principles applied by other modalities and some more specific features. In general terms, malignancy is more likely with larger masses having a broad-based attachment, involving more than one cardiac chamber or great vessel, and with associated pericardial or extracardiac extension. More specifically, T1W and T2W images use the biochemical composition of masses to assist with diagnosis. High signal intensity on T1W images can be due to cystic lesions with a high protein content, fatty tumours (lipoma, liposarcoma), recent haemorrhage and melanoma. Low signal intensity on T1W is seen in cysts with low protein content, within vascular malformations, in calcified lesions, or if the mass contains air. Subsequent T2W imaging demonstrates cysts as having high signal intensity, and the addition of a fat saturation prepulse distinguishes lipid content. Rest perfusion first-pass CMR shows contrast uptake into vascular tumours (haemangioma, angiosarcoma) and may also identify small vessels. In malignancy, EGE typically demonstrates dark areas with surrounding enhancement from necrotic tissue, while LGE can show enhancement due to expanded interstitial space such as in fibrosis (Figure 5.5). Such enhancement is absent in cystic lesions and most benign tumours, with exceptions being haemangiomas, myxomas and fibromas (Figure 5.6).

Pericardial disease

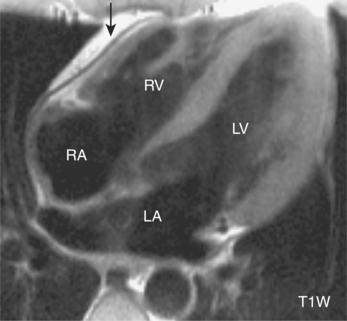

The pericardium is a thin double-layered sac that encompasses the heart and proximal great vessels. Its inner serosal layer adheres to the myocardium forming the visceral pericardium or epicardium, extends up over the proximal great vessels and reflects back on itself to become contiguous with the outer layer. This fibrous outer parietal layer has attachments to the diaphragm, sternum, costal cartilages and the spinal column. The two layers are separated by a space containing 15 to 35 ml of serous fluid and total pericardial thickness is 1 to 2 mm. At the base of the heart the pericardial reflection forms sinuses and recesses, with the reflection adjacent to the ascending aorta potentially confused with a proximal aortic dissection by the unwary (Figure 10.10). Since fat usually surrounds the pericardium and is also present beneath the epicardium, the pericardium is often sandwiched between two layers of fat. This makes it easier to visualize edge-on with CMR and gives the slightly higher normal value of up to 4 mm for pericardial thickness. Normal pericardium has low signal intensity by GE and SE imaging techniques (Figure 5.7). Of note, a dark line can be present at the interface between myocardium and epicardial fat on GE images due to artefact. This appearance is caused by the phenomenon of chemical shift phase cancellation and should not be interpreted as pericardium (see section 10.6, Chemical Shift Edge Artefacts).

Figure 5.7 Four-chamber T1W FSE image showing normal pericardial appearance in front of the RV (black arrow).

Acute pericarditis and pericardial effusion

Acute pericarditis may be accompanied by symptoms and signs of heart failure or arrhythmias if there is concomitant myocarditis. CMR findings range from no abnormality to regional WMA, pericardial thickening and pericardial effusion. The heart is imaged in different planes to determine the greatest extent of thickening or effusion, especially in cases of loculation. An effusion less than 10 mm wide is considered small whereas large effusions are greater than 20 mm. Both thickened pericardium and effusions can show low signal intensity on T1W SE imaging while GE techniques reveal non-haemorrhagic effusions to have high signal intensity (Figure 5.8). The appearance of haemorrhagic effusions depends on the age of the pericardial haematoma. Acutely, there is high signal intensity on T1W SE and lower signal intensity on GE images, while more chronic haematomas exhibit heterogeneous signal intensities by SE techniques. Differentiation of transudates from exudates and chylous effusions is through T1W SE imaging. Signal intensity is low in transudates but high in chylous collections, with an intermediate appearance in exudates.

With massive effusion, ECG amplitude may diminish making it difficult to trigger cardiac imaging. CMR assessment can also be limited in patients who are significantly symptomatic since they have a tachycardia and find it difficult to lie flat within the magnet for prolonged periods.

Constrictive pericarditis

Following inflammation or bleeding into the pericardial space, fibrosis and calcification of the pericardium may ensue and the pericardium becomes thickened and stiff. This progressively restricts and impairs the filling of the cardiac chambers. Diastolic pressures are elevated and equalized in all four cardiac chambers. Impaired diastolic function leads to tachycardia and volume expansion, resulting in systemic venous congestion. Systolic function is usually preserved unless there is associated myocardial disease. The heart is insulated from changes in intrathoracic pressure that occur with respiration and atrial and ventricular filling patterns vary significantly with inspiration and expiration, resulting in ventricular interdependence. During inspiration, right-sided filling is increased, the ventricular septum deviates to the left, and left-sided filling correspondingly decreases. The converse occurs at expiration.

The distinction between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy is difficult but important clinically and imaging techniques such as CMR and cardiac CT are useful in diagnosis. The diagnostic hallmark of constrictive pericarditis is pericardial thickening with or without calcification in the presence of suggestive symptoms and signs of constriction (Figure 5.9). Care should be taken when evaluating pericardial thickness since oblique views yield falsely high values and several planes must be assessed and used in measurements. The absence of pericardial thickening/calcification does not exclude the presence of constriction and a thickened pericardium does not always equate to constrictive pericarditis. It is therefore crucial to evaluate concomitant functional consequences and CMR is well-suited for this purpose.

A thickened pericardium as well as pericardial effusions can often be identified at the early low-resolution FSE sequence. Pericardial thickness is definitively measured on subsequent T1W FSE views and differentiated from effusion with SSFP cines acquired in these same planes. In the presence of effusion, pericardial thickness can be determined by use of gadolinium which can outline the visceral and parietal layers. Chronic fibrotic pericardium shows late enhancement, which is also seen with associated myocardial fibrosis or infarction. Areas of calcification appear as regions of attenuated signal intensity on CMR but CT is recommended for accurate assessment of this feature. Other findings include typically normal-sized or small ventricles with normal ejection fraction, dilated atria and vena cavae, pleural effusions, plethoric hepatic veins, hepatic enlargement and ascites. The ventricles may assume a tube-like configuration. The presence of epicardial fat separating the epimyocardium from the thickened visceral pericardium is also a useful finding for the surgeon when planning surgical pericardiectomy.

Pericardial cyst and diverticula

Pericardial cysts are uncommon remnants of defective pericardial embryologic development. They are benign and occur as round, sharply demarcated, fluid-filled bodies, found most commonly in the right cardiophrenic angle but also in the hilar and mediastinal regions. They do not communicate with the pericardial space. Using T2W SE images they typically exhibit high signal intensity, while on T1W SE images they show intermediate or low signal intensities (Figure 5.10). There is no enhancement with gadolinium contrast.

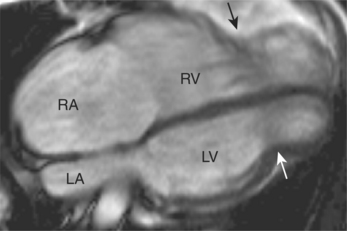

Congenital absence of the pericardium

Absence of the pericardium is rare and often asymptomatic. The defect is usually left-sided and partial but can be right-sided, diaphragmatic or complete. Associated congenital cardiac anomalies include atrial septal defects (ASDs), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF). The heart shifts to the left and posteriorly, and with partial left-sided absence the left atrial appendage may be dilated. Herniation of the left atrial appendage through a partial defect may lead to strangulation and sudden death. CMR can reveal the defect, associated cardiac anomalies and displacement, and herniation (Figure 5.11).

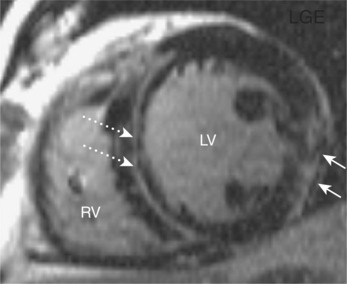

Myocarditis

Myocarditis can be caused by a wide variety of infectious agents and detected with the technique of LGE. Patterns of enhancement do not correspond to infarction in a coronary artery territory and are characteristically subepicardial and frequently located in the lateral free wall (Figure 5.12). These appearances in conjunction with the appropriate clinical setting can obviate the necessity for cardiac catheterization and subsequent endomyocardial biopsy in selected patients. Follow-up of individuals with significant enhancement abnormalities, with either echocardiography or CMR, is also advisable to determine long-term ventricular function.