Cardiac disorders

Recent developments in paediatric cardiac disease are:

• Lesions are being increasingly identified on antenatal ultrasound screening

• Most lesions are diagnosed by echocardiography, the mainstay of diagnostic imaging

• MRI allows three-dimensional reconstruction of complex cardiac disorders, assessment of haemodynamics and flow patterns and assists interventional cardiology, reducing the need for cardiac catheterisation

• Most defects can be corrected by definitive surgery at the initial operation

• An increasing number of defects (60%) are treated non-invasively, e.g. persistent ductus arteriosus

• New therapies are available to treat pulmonary hypertension and delay transplantation

• The overall infant cardiac surgical mortality has been reduced from approximately 20% in 1970 to 2% in 2010.

Aetiology

Genetic causes are increasingly recognised in the aetiology of congenital heart disease, now in more than 10%. These might affect whole chromosomes, point mutations or microdeletions (Table 17.1). Polygenic abnormalities probably explain why having a child with congenital heart disease doubles the risk for subsequent children and the risk is higher still if either parent has congenital heart disease. A small proportion are related to external teratogens.

Table 17.1

Causes of congenital heart disease

| Cardiac abnormalities | Frequency | |

| Maternal disorders | ||

| Rubella infection | Peripheral pulmonary stenosis, PDA | 30–35% |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | Complete heart block (anti-Ro and anti-La antibody) | 35% |

| Diabetes mellitus | Incidence increased overall | 2% |

| Maternal drugs | ||

| Warfarin therapy | Pulmonary valve stenosis, PDA | 5% |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | ASD, VSD, tetralogy of Fallot | 25% |

| Chromosomal abnormality | ||

| Down syndrome (trisomy 21) | Atrioventricular septal defect, VSD | 30% |

| Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18) | Complex | 60–80% |

| Patau syndrome (trisomy 13) | Complex | 70% |

| Turner syndrome (45XO) | Aortic valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta | 15% |

| Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion | Aortic arch anomalies, tetralogy of Fallot, common arterial trunk | 80% |

| Williams syndrome (7q11.23 microdeletion) | Supravalvular aortic stenosis, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis | 85% |

| Noonan syndrome (PTPN11 mutation and others) | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial septal defect, pulmonary valve stenosis | 50% |

ASD, atrial septal defect; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Circulatory changes at birth

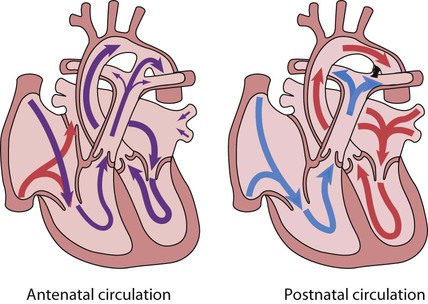

In the fetus, the left atrial pressure is low, as relatively little blood returns from the lungs. The pressure in the right atrium is higher than in the left, as it receives all the systemic venous return including blood from the placenta. The flap valve of the foramen ovale is held open, blood flows across the atrial septum into the left atrium and then into the left ventricle, which in turn pumps it to the upper body (Fig. 17.1).

Presentation

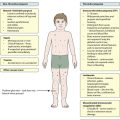

Congenital heart disease presents with:

Heart failure

Signs

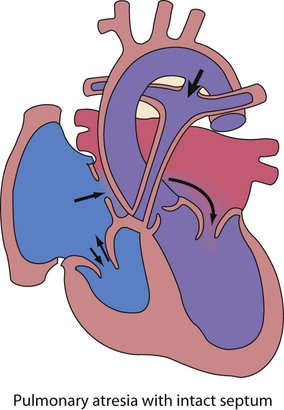

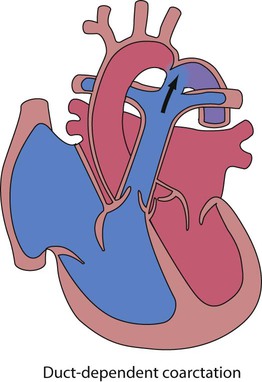

In the first week of life, heart failure (Box 17.2) usually results from left heart obstruction, e.g. coarctation of the aorta. If the obstructive lesion is very severe then arterial perfusion may be predominantly by right-to-left flow of blood via the arterial duct, so-called duct-dependent systemic circulation (Fig. 17.2). Closure of the duct under these circumstances rapidly leads to severe acidosis, collapse and death unless ductal patency is restored (Case History 17.1).

Cyanosis

• Peripheral cyanosis (blueness of the hands and feet) may occur when a child is cold or unwell from any cause or with polycythaemia

• Central cyanosis, seen on the tongue as a slate blue colour, is associated with a fall in arterial blood oxygen tension. It can only be recognised clinically if the concentration of reduced haemoglobin in the blood exceeds 5 g/dl, so it is less pronounced if the child is anaemic

• Check with a pulse oximeter that an infant’s oxygen saturation is normal (≥94%). Persistent cyanosis in an otherwise well infant is nearly always a sign of structural heart disease.

• Cardiac disorders – cyanotic congenital heart disease

• Respiratory disorders, e.g. surfactant deficiency, meconium aspiration, pulmonary hypoplasia, etc.

• Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) – failure of the pulmonary vascular resistance to fall after birth

• Infection – septicaemia from group B streptococcus and other organisms

This is summarised in Table 17.2.

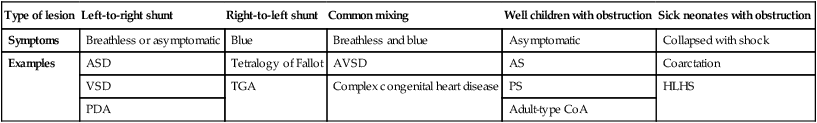

Table 17.2

Types of presentation with congenital heart disease

| Type of lesion | Left-to-right shunt | Right-to-left shunt | Common mixing | Well children with obstruction | Sick neonates with obstruction |

| Symptoms | Breathless or asymptomatic | Blue | Breathless and blue | Asymptomatic | Collapsed with shock |

| Examples | ASD | Tetralogy of Fallot | AVSD | AS | Coarctation |

| VSD | TGA | Complex congenital heart disease | PS | HLHS | |

| PDA | Adult-type CoA |

ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; AVSD, atrioventricular; AS, aortic stenosis; PS, pulmonary stenosis; CoA, coarctation of the aorta; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

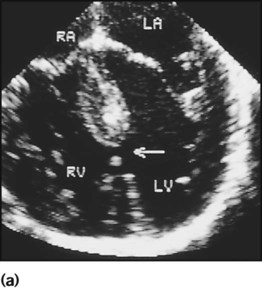

Diagnosis

If congenital heart disease is suspected, a chest radiograph and ECG (Box 17.3) should be performed. Although rarely diagnostic, they may be helpful in establishing that there is an abnormality of the cardiovascular system and as a baseline for assessing future changes. Echocardiography, combined with Doppler ultrasound, enables almost all causes of congenital heart disease to be diagnosed. Even when a paediatric cardiologist is not available locally a specialist echocardiography opinion may be available via telemedicine, or else transfer to the cardiac centre will be necessary. A specialist opinion is required if the child is haemodynamically unstable, if there is heart failure, if there is cyanosis, when the oxygen saturations are <94% due to heart disease and when there are reduced volume pulses.

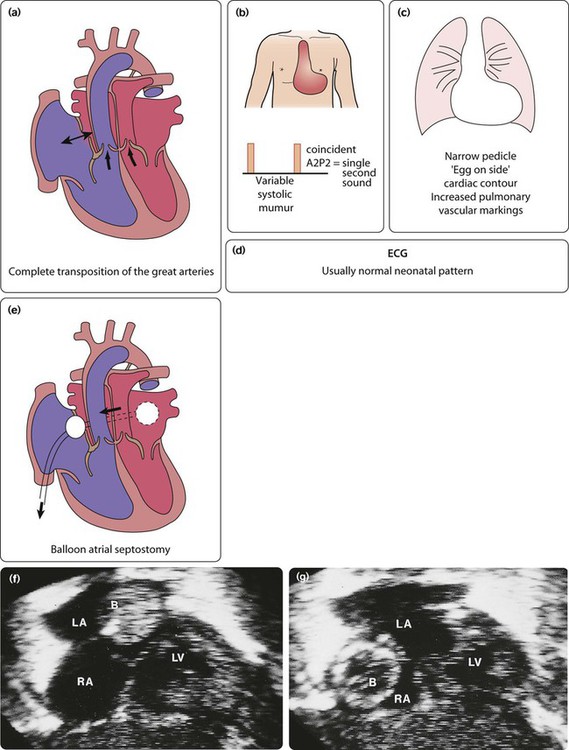

Left-to-right shunts

Atrial septal defect

There are two main types of atrial septal defect (ASD):

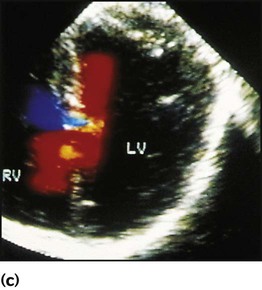

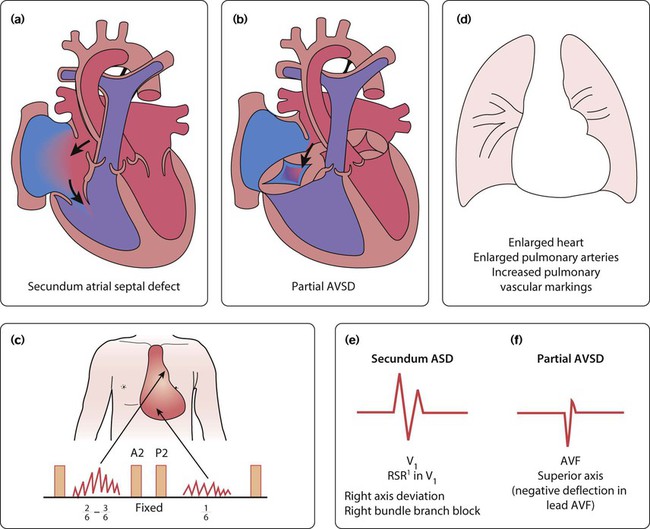

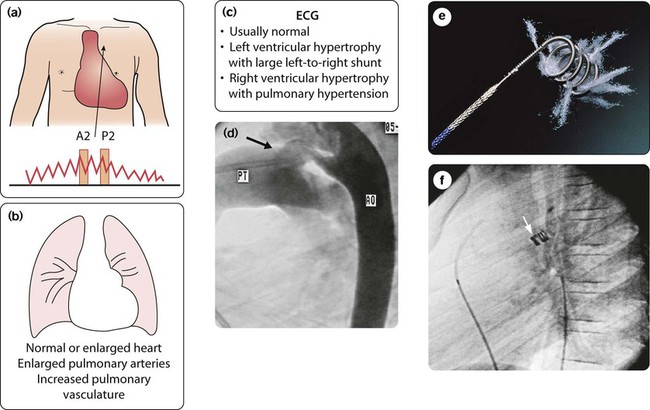

• Secundum ASD (80% of ASDs) (Fig. 17.5a)

• Partial atrioventricular septal defect (primum ASD, pAVSD) (Fig 17.5b).

Partial AVSD is a defect of the atrioventricular septum and is characterised by:

• An inter-atrial communication between the bottom end of the atrial septum and the atrioventricular valves (primum ASD)

• Abnormal atrioventricular valves, with a left atrioventricular valve which has three leaflets and tends to leak (regurgitant valve).

Clinical features

Physical signs (Fig. 17.5c)

• An ejection systolic murmur best heard at the upper left sternal edge – due to increased flow across the pulmonary valve because of the left-to-right shunt

• A fixed and widely split second heart sound (often difficult to hear) – due to the right ventricular stroke volume being equal in both inspiration and expiration

• With a partial AVSD, an apical pansystolic murmur from atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Investigations

ECG

• Secundum ASD – partial right bundle branch block is common (but may occur in normal children), right axis deviation due to right ventricular enlargement (Fig. 17.5e)

• Partial AVSD – a ‘superior’ QRS axis (mainly negative in AVF) (Fig 17.5f). This occurs because there is a defect of the middle part of the heart where the atrioventricular node is. The displaced node then conducts to the ventricles superiorly, giving the abnormal axis.

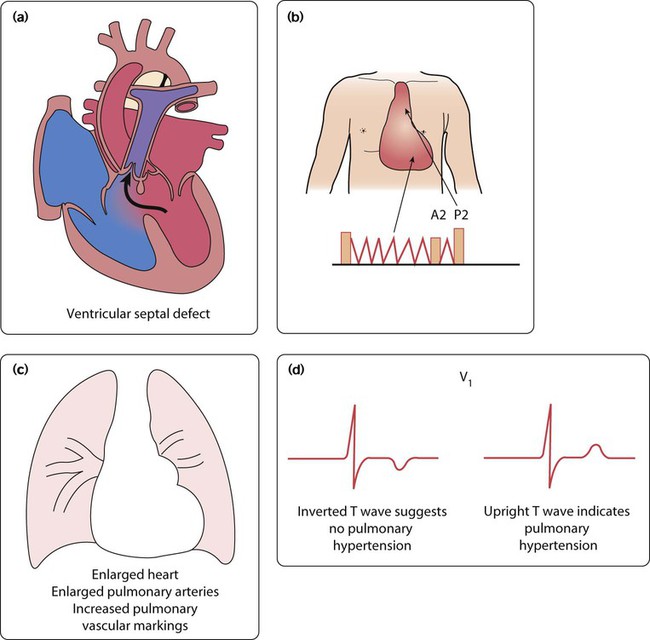

Management

Children with significant atrial septal defect (large enough to cause right ventricle dilation) will require treatment. For secundum ASDs, this is by cardiac catheterisation with insertion of an occlusion device (Fig 17.5g), but for partial AVSD, surgical correction is required. Treatment is usually undertaken at about 3–5 years of age in order to prevent right heart failure and arrhythmias in later life.

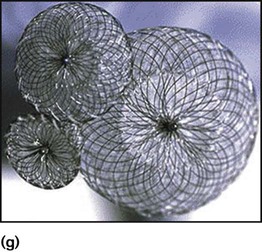

Ventricular septal defects

Large VSDs

These defects are the same size or bigger than the aortic valve (Fig. 17.6a).

Clinical features

Physical signs (Fig. 17.6b)

• Tachypnoea, tachycardia and enlarged liver from heart failure

• Soft pansystolic murmur or no murmur (implying large defect)

• Apical mid-diastolic murmur (from increased flow across the mitral valve after the blood has circulated through the lungs)

• Loud pulmonary second sound (P2) – from raised pulmonary arterial pressure.

Management

Drug therapy for heart failure is with diuretics, often combined with captopril. Additional calorie input is required. There is always pulmonary hypertension in children with large VSD and left-to-right shunt. This will ultimately lead to irreversible damage of the pulmonary capillary vascular bed (see Eisenmenger syndrome, below). To prevent this, surgery is usually performed at 3–6 months of age in order to:

Persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA, persistent arterial duct)

The ductus arteriosus connects the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. In term infants, it normally closes shortly after birth. In persistent ductus arteriosus it has failed to close by 1 month after the expected date of delivery due to a defect in the constrictor mechanism of the duct. The flow of blood across a persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is then from the aorta to the pulmonary artery (i.e. left to right), following the fall in pulmonary vascular resistance after birth. In the pre-term infant, the presence of a persistent ductus arteriosus is not from congenital heart disease but due to prematurity. This is described in Chapter 9.

Clinical features

Most children present with a continuous murmur beneath the left clavicle (Fig. 17.7a). The murmur continues into diastole because the pressure in the pulmonary artery is lower than that in the aorta throughout the cardiac cycle. The pulse pressure is increased, causing a collapsing or bounding pulse. Symptoms are unusual, but when the duct is large there will be increased pulmonary blood flow with heart failure and pulmonary hypertension.

Investigations

The chest radiograph and ECG are usually normal, but if the PDA is large and symptomatic the features on chest radiograph (Fig. 17.7b) and ECG (Fig. 17.7c) are indistinguishable from those seen in a patient with a large VSD. However, the duct is readily identified on echocardiography.

Right-to-left shunts

Hyperoxia (nitrogen washout) test

Management

• Stabilise the airway, breathing and circulation (ABC), with artificial ventilation if necessary

• Start prostaglandin infusion (PGE, 5 ng/kg per min). Most infants with cyanotic heart disease presenting in the first few days of life are duct dependent; i.e. there is reduced mixing between the pink oxygenated blood returning from the lungs and the blue deoxygenated blood from the body. Maintenance of ductal patency is the key to early survival of these children. Observe for potential side-effects – apnoea, jitteriness and seizures, flushing, vasodilatation and hypotension.

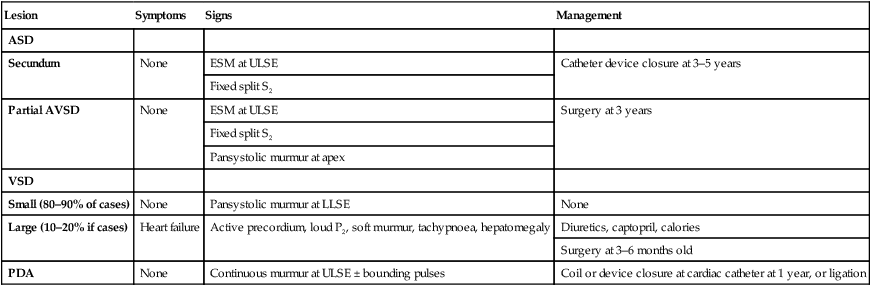

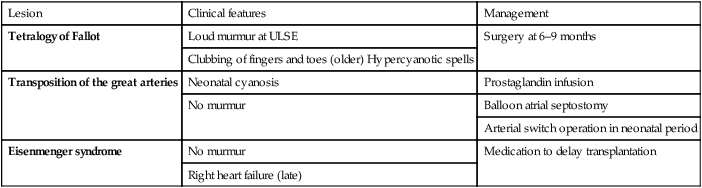

Tetralogy of Fallot

This is the most common cause of cyanotic congenital heart disease (Fig. 17.8a).

Clinical features

In tetralogy of Fallot, as implied by the name, there are four cardinal anatomical features:

• Overriding of the aorta with respect to the ventricular septum

• Subpulmonary stenosis causing right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Signs

• Clubbing of the fingers and toes will develop in older children

• A loud harsh ejection systolic murmur at the left sternal edge from day 1 of life (Fig. 17.8b). With increasing right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, which is predominantly muscular and below the pulmonary valve, the murmur will shorten and cyanosis will increase.

Management

• Initial management is medical, with definitive surgery at around 6 months of age. It involves closing the VSD and relieving right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, sometimes with an artificial patch, which extends across the pulmonary valve.

• Infants who are very cyanosed in the neonatal period require a shunt to increase pulmonary blood flow. This is usually done by surgical placement of an artificial tube between the subclavian artery and the pulmonary artery (a modified Blalock–Taussig shunt), or sometimes by balloon dilatation of the right ventricular outflow tract.

• Hypercyanotic spells are usually self-limiting and followed by a period of sleep. If prolonged (beyond about 15 min), they require prompt treatment with:

– sedation and pain relief (morphine is excellent)

– intravenous propranolol (or an α adrenoceptor agonist), which probably works both as a peripheral vasoconstrictor and by relieving the subpulmonary muscular obstruction that is the cause of reduced pulmonary blood flow

– intravenous volume administration

– bicarbonate to correct acidosis

– muscle paralysis and artificial ventilation in order to reduce metabolic oxygen demand.

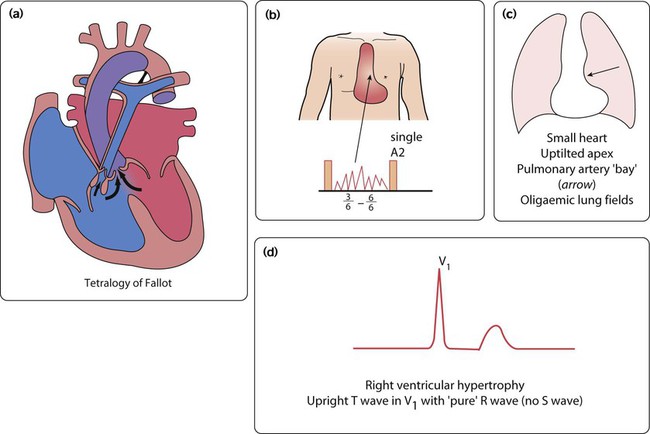

Transposition of the great arteries

The aorta is connected to the right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery is connected to the left ventricle (discordant ventriculo–arterial connection). The blue blood is therefore returned to the body and the pink blood is returned to the lungs (Fig. 17.9a). There are two parallel circulations – unless there is mixing of blood between them this condition is incompatible with life. Fortunately, there are a number of naturally occurring associated anomalies, e.g. VSD, ASD and PDA, as well as therapeutic interventions which can achieve this mixing in the short term.

Management

• In the sick cyanosed neonate, the key is to improve mixing.

• Maintaining the patency of the ductus arteriosus with a prostaglandin infusion is mandatory.

• A balloon atrial septostomy may be a life-saving procedure which may need to be performed in 20% of those with transposition of the great arteries (Fig. 17.9e–g). A catheter, with an inflatable balloon at its tip, is passed through the umbilical or femoral vein and then on through the right atrium and foramen ovale. The balloon is inflated within the left atrium and then pulled back through the atrial septum. This tears the atrial septum, renders the flap valve of the foramen ovale incompetent, and so allows mixing of the systemic and pulmonary venous blood within the atrium.

• All patients with transposition of the great arteries will require surgery, which is usually the arterial switch procedure in the neonatal period. In this operation, performed in the first few days of life, the pulmonary artery and aorta are transected above the arterial valves and switched over. In addition, the coronary arteries have to be transferred across to the new aorta.

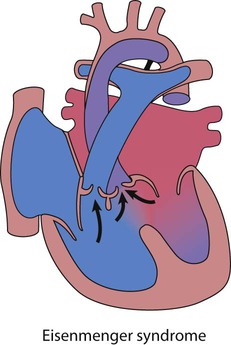

Eisenmenger syndrome

If high pulmonary blood flow due to a large left-to-right shunt or common mixing is not treated at an early stage, then the pulmonary arteries become thick walled and the resistance to flow increases (Fig. 17.10). Gradually, those children that survive, become less symptomatic, as the shunt decreases. Eventually, at about 10–15 years, the shunt reverses and the teenager becomes blue, which is Eisenmenger syndrome. This situation is progressive and the adult will die in right heart failure at a variable age, usually in the fourth or fifth decade of life. Treatment is aimed at prevention of this condition, with early intervention for high pulmonary blood flow. Transplantation is not easily available although there are now medicines to palliate such pulmonary vascular disease (see Pulmonary hypertension, below).

Common mixing (blue and breathless)

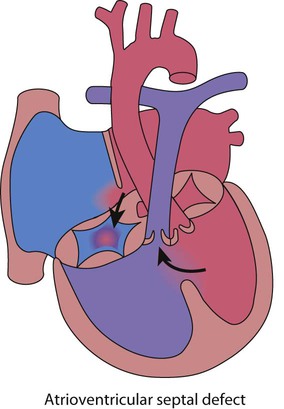

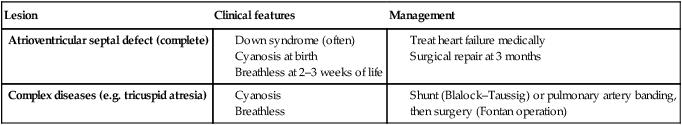

Atrioventricular septal defect (complete)

This is most commonly seen in children with Down syndrome (Fig. 17.11). A complete atrioventricular septal defect (cAVSD) is a defect in the middle of the heart with a single five-leaflet (common) valve between the atria and ventricles which stretches across the entire atrioventricular junction and tends to leak. As there is a large defect there is pulmonary hypertension.

Features of a complete atrioventricular septal defect are:

• Presentation on antenatal ultrasound screening

• Cyanosis at birth or heart failure at 2–3 weeks of life

• No murmur heard, the lesion being detected on routine echocardiography screening in a newborn baby with Down syndrome

• There is always a superior axis on the ECG

• Management is to treat heart failure medically (as for large VSD) and surgical repair at 3–6 months of age.

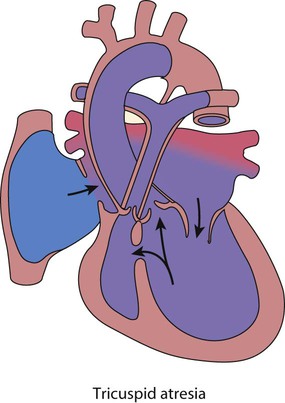

Complex congenital heart disease

Tricuspid atresia

In tricuspid atresia (Fig. 17.12), only the left ventricle is effective, the right being small and non-functional.

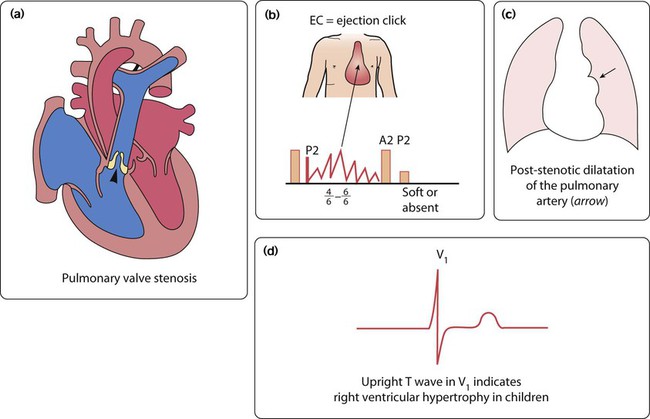

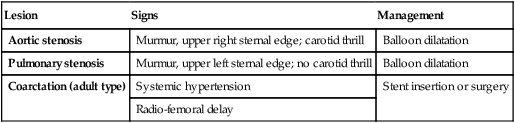

Outflow obstruction in the well child

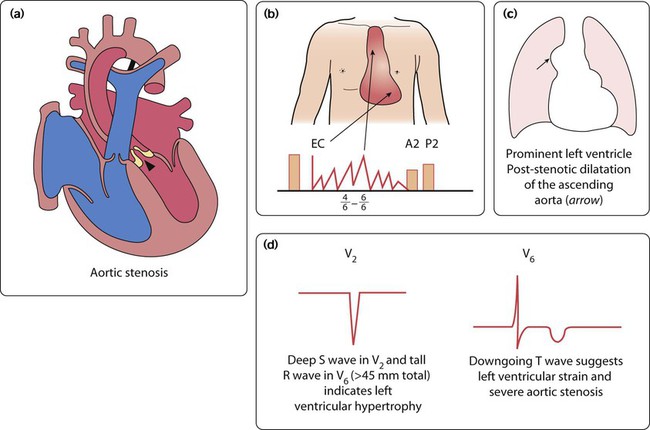

Aortic stenosis

The aortic valve leaflets are partly fused together, giving a restrictive exit from the left ventricle (Fig. 17.13a). There may be one to three aortic leaflets. Aortic stenosis may not be an isolated lesion. It is often associated with mitral valve stenosis and coarctation of the aorta, and their presence should always be excluded.

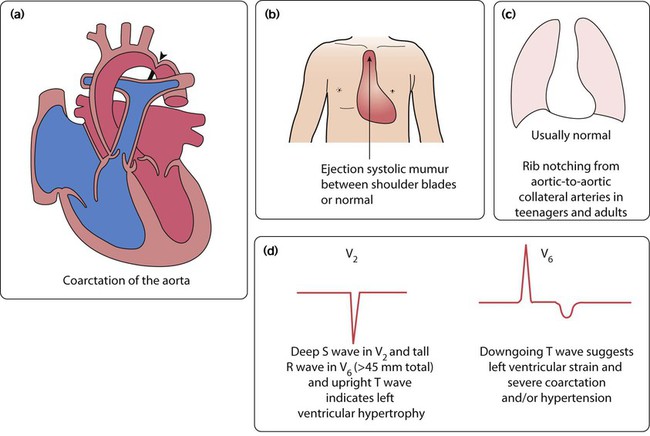

Adult-type coarctation of the aorta

This uncommon lesion (Fig. 17.15a) is not duct dependent. It gradually becomes more severe over many years.

Clinical features (Fig 17.15b)

Outflow obstruction in the sick infant

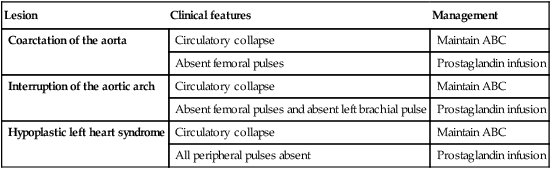

• In all of these children, they usually present sick with heart failure and shock in the neonatal period, unless diagnosed on antenatal ultrasound

• Management is to resuscitate first (ABC)

• Prostaglandin should be commenced at the earliest opportunity

• Referral is made to a cardiac centre for early surgical intervention.

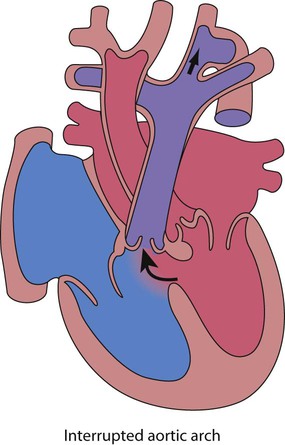

Interruption of the aortic arch

• Uncommon, with no connection between the proximal aorta and distal to the arterial duct, so that the cardiac output is dependent on right-to-left shunt via the duct Fig. 17.16

• Presentation is with shock in the neonatal period as above

• Complete correction with closure of the VSD and repair of the aortic arch is usually performed within the first few days of life.

• Association with other conditions (DiGeorge syndrome – absence of thymus, palatal defects, immunodeficiency and hypocalcaemia and 22q11.2 gene micro-deletion).

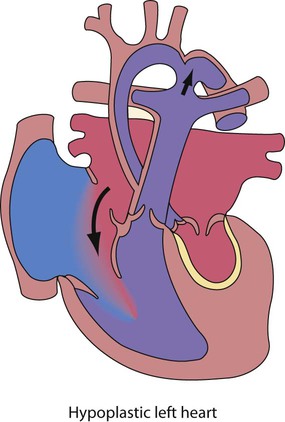

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome

In this condition there is underdevelopment of the entire left side of the heart (Fig. 17.17). The mitral valve is small or atretic, the left ventricle is diminutive and there is usually aortic valve atresia. The ascending aorta is very small, and there is almost invariably coarctation of the aorta.

Cardiac arrhythmias

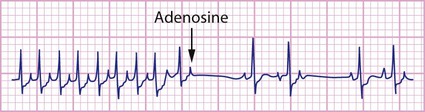

Supraventricular tachycardia

Investigation

The ECG will generally show a narrow complex tachycardia of 250–300 beats/min (Fig. 17.18). It may be possible to discern a P wave after the QRS complex due to retrograde activation of the atrium via the accessory pathway. If heart failure is severe, there may be changes suggestive of myocardial ischaemia, with T-wave inversion in the lateral precordial leads. When in sinus rhythm, a short P–R interval may be discernible. In the Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW) syndrome, the early antegrade activation of the ventricle via the pathway results in a short P–R interval and a delta wave.

Management

• Circulatory and respiratory support – tissue acidosis is corrected, positive pressure ventilation if required

• Vagal stimulating manoeuvres, e.g. carotid sinus massage or cold ice pack to face, successful in about 80%

• Intravenous adenosine – the treatment of choice. This is safe and effective, inducing atrioventricular block after rapid bolus injection. It terminates the tachycardia by breaking the re-entry circuit that is set up between the atrioventricular node and accessory pathway. It is given incrementally in increasing doses

• Electrical cardioversion with a synchronised DC shock (0.5–2 J/kg body weight) if adenosine fails.

Congenital complete heart block

This is a rare condition (Fig. 17.19) which is usually related to the presence of anti-Ro or anti-La antibodies in maternal serum. These mothers will have either manifest or latent connective tissue disorders. Subsequent pregnancies are often affected. This antibody appears to prevent normal development of the electrical conduction system in the developing heart, with atrophy and fibrosis of the atrioventricular node. It may cause fetal hydrops, death in utero and heart failure in the neonatal period. However, most remain symptom-free for many years, but a few become symptomatic with presyncope or syncope. All children with symptoms require insertion of an endocardial pacemaker. There are other rare causes of complete heart block.

Syncope

This is a common symptom in teenagers and usually does not represent cardiac disease.

• Neurocardiogenic – prolonged standing and vagal symptoms

• Situational – defecation, urination, cough or swallowing

• Orthostatic – BP fall > 20 mmHg after 3 min

• Arrhythmic – heart block, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia.

In most, the cause is non-cardiac. Features suggestive of a cardiac cause are:

Check blood pressure and signs of cardiac disease (murmur, femoral pulses, Marfan syndrome).

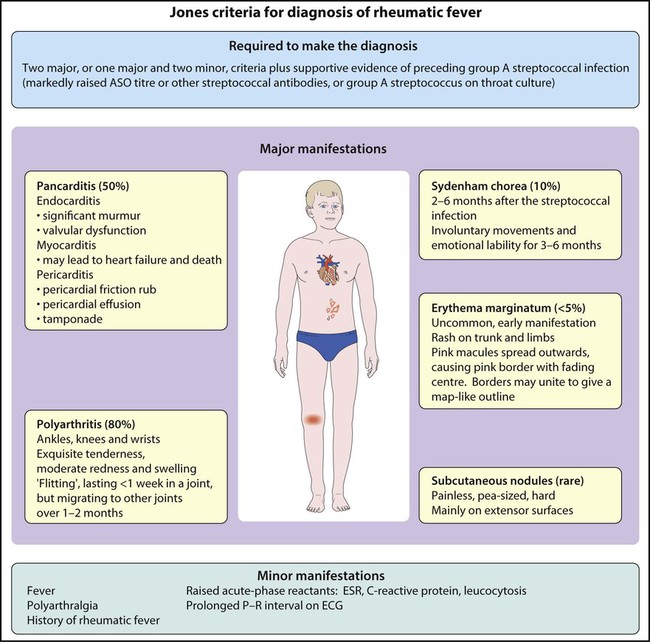

Rheumatic fever

Clinical features

After a latent interval of 2–6 weeks following a pharyngeal infection, polyarthritis, mild fever and malaise develop. The clinical features and diagnostic criteria are shown in Figure 17.20.

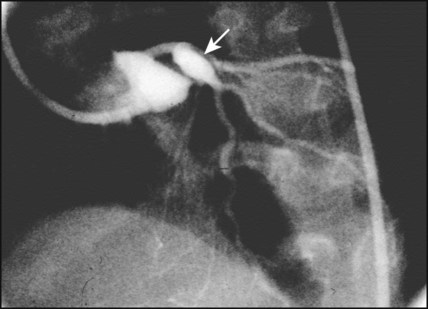

Kawasaki disease

This mainly affects children of 6 months to 5 years. Clinical features are described in Chapter 14. It is uncommon but can cause significant cardiac disease. An echocardiogram is performed at diagnosis which may show a pericardial effusion, myocardial disease (poor contractility), endocardial disease (valve regurgitation) or coronary disease with aneurysm formation, which can be giant (>8 mm in diameter). If the coronary arteries are abnormal, angiography (Fig. 17.22) or MRI will be required.

Pulmonary hypertension

This is of increasing importance in paediatric cardiology, as there is now effective medication for most causes. It can be caused by a number of different diseases (Box 17.4). From the cardiac perspective, most children with pulmonary hypertension (high pulmonary artery pressure, mean >25 mmHg), have a large post-tricuspid shunt with high pulmonary blood flow and low resistance, e.g. VSD, AVSD or PDA. The pressure falls to normal if the defect is corrected by surgery within 6 months of age. If these children are left untreated, however, the high flow and pressure causes irreversible damage to the pulmonary vascular bed (pulmonary vascular disease), which is not correctable other than by heart/lung transplantation.