Chapter 14

Cardiac Catheterization, Angiography, IVUS, and FFR

1. What are generally accepted indications for cardiac catheterization?

Class III-IV angina despite medical treatment or intolerance of medical therapy

Class III-IV angina despite medical treatment or intolerance of medical therapy

High-risk results on noninvasive stress testing

High-risk results on noninvasive stress testing

Sustained (more than 30 seconds) monomorphic ventricular tachycardia or nonsustained (less than 30 seconds) polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Sustained (more than 30 seconds) monomorphic ventricular tachycardia or nonsustained (less than 30 seconds) polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Sudden cardiac death survivors

Sudden cardiac death survivors

Most patients with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) who have high-risk features and no contraindications to early cardiac catheterization and revascularization

Most patients with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) who have high-risk features and no contraindications to early cardiac catheterization and revascularization

Systolic dysfunction and stress testing results suggesting multivessel disease and potential benefit from revascularization

Systolic dysfunction and stress testing results suggesting multivessel disease and potential benefit from revascularization

Recurrent typical angina within 9 months of percutaneous coronary revascularization

Recurrent typical angina within 9 months of percutaneous coronary revascularization

For assessment of valvular dysfunction or other hemodynamic assessment when the results of echocardiography are indeterminate

For assessment of valvular dysfunction or other hemodynamic assessment when the results of echocardiography are indeterminate

As part of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

As part of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

Patients post-STEMI (with or without thrombolytic therapy) with high-risk features, depressed ejection fraction, or high-risk results on subsequent stress testing

Patients post-STEMI (with or without thrombolytic therapy) with high-risk features, depressed ejection fraction, or high-risk results on subsequent stress testing

Within 36 hours of STEMI in appropriate patients who develop cardiogenic shock

Within 36 hours of STEMI in appropriate patients who develop cardiogenic shock

In select patients who are to undergo valve replacement or repair

In select patients who are to undergo valve replacement or repair

In assessment and management of patients with congenital heart disease and cardiac transplant recipients

In assessment and management of patients with congenital heart disease and cardiac transplant recipients

2. What are the risks of cardiac catheterization?

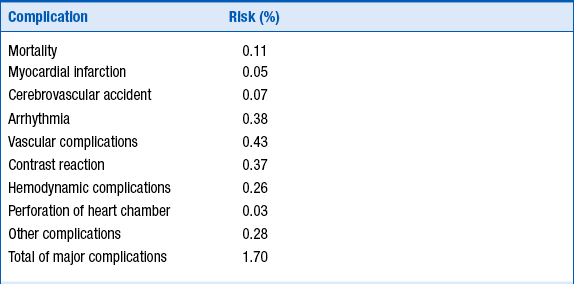

The risks of cardiac catheterization will depend to some extent on the individual patient. For “all comers,” the risk of death is approximately 1 in 1000, with the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke rarer than 1 in 1000. The risk of any major complication in “all comers” is less than 1%. These risks are summarized in Table 14-1.

TABLE 14-1

RISKS OF CARDIAC CATHETERIZATION AND CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY

Reproduced from David CJ, Bonow RO: Cardiac Catheterization. In Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, p 461.

3. How are coronary lesions assessed?

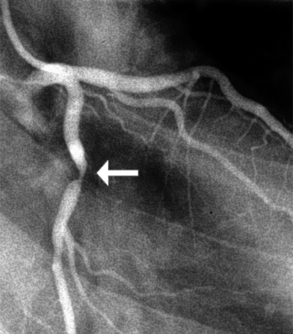

Coronary lesions are most commonly assessed in day-to-day practice based on subjective visual impression (Fig. 14-1). Lesions are subjectively given a percent stenosis, ideally based on ocular assessment of at least two orthogonal images of the lesion. Studies have shown interobserver and intraobserver variability in judging coronary stenosis from as little as 7% to as much as 50%. Quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) more objectively assesses the lesion severity than does “ocular judgment,” but is not commonly used in day-to-day practice. QCA generally grades lesions as less severe than does subjective ocular judgment of a lesion’s severity. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can more accurately assess the total plaque burden and severity of a lesion than can ocular judgment or QCA. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) is increasingly being used to measure the severity of a lesion from a physiologic standpoint (see later).

Figure 14-1 Coronary angiography of the left coronary artery demonstrates an approximate 90% lesion (arrow) in the left coronary artery.

4. What is considered a “significant” stenosis?

The classification of significant stenosis depends on the clinical context and what one considers “significant.” Coronary flow reserve (the increase in coronary blood flow in response to agents that lead to microvascular dilation) begins to decrease when a coronary artery stenosis is 50% or more of the luminal diameter. However, basal coronary flow does not begin to decrease until the lesion is 80% to 90% of the luminal diameter.

5. What is fractional flow reserve (FFR)?

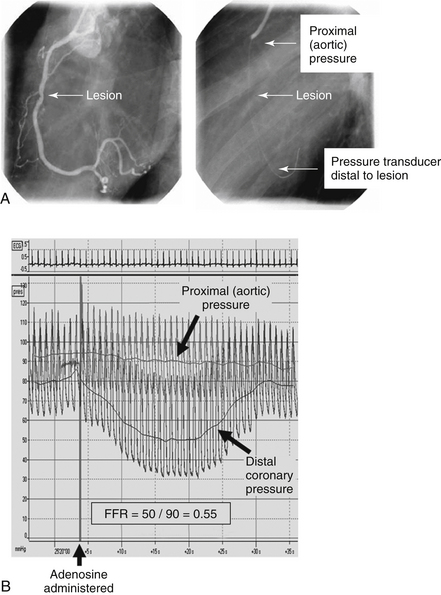

Physiologic assessment of blood flow through a stenotic lesion can be safely and reliably performed in the catheterization laboratory using a coronary wire with a pressure sensor at its tip. The wire is advanced across the lesion of interest, and the ratio of distal coronary pressure to proximal aortic pressure is assessed after maximal hyperemia is achieved (Fig 14-2). This ratio is called FFR. Normal values are close to 1, and a ratio less than 0.75 to 0.80 is taken as indicating a “physiologically significant stenosis.” Adenosine is typically used as a pharmacologic agent to achieve maximal hyperemia.

Figure 14-2 Fractional flow reserve. A, An intermediate lesion in the right coronary artery. The pressure wire is advanced distal to the lesion. B, Pressure tracings proximal to and distal to the lesion. There is a notable fall in distal perfusion pressure after administration of adenosine, indicating a hemodynamically significant lesion.

6. How is FFR used to guide coronary stenting?

7. During cardiac catheterization, how is aortic or mitral regurgitation graded?

For aortic regurgitation, an aortogram is performed in the ascending thoracic aorta above the aortic valve and the amount of contrast that regurgitates into the left ventricle is noted. For mitral regurgitation, a left ventriculogram is performed and the amount of contrast that regurgitates into the left atrium is noted. The systems used to grade the degree of regurgitation are similar for the two valvular abnormalities, and based on a 1+ to 4+ system, where 1+ is little if any regurgitation and 4+ is profound or severe regurgitation. Regurgitation of 3+ or 4+ is often considered “surgical” regurgitation, although the criteria for surgery are more complex than this (see Chapters 30 and 31 on aortic valve disease and on mitral valve disease, respectively). Table 14-2 summarizes the grading of regurgitant lesions as assessed by cardiac catheterization and “ballpark” regurgitant fractions for each degree of regurgitation.

TABLE 14-2

VISUAL ASSESSMENT OF VALVULAR REGURGITATION AND APPROXIMATE CORRESPONDING REGURGITANT FRACTION∗

| Visual Appearance of Regurgitation | Designated Grading (Severity) of Valvular Regurgitation | Approximate Corresponding Regurgitant Fraction |

| Minimal regurgitant jet seen. Clears rapidly from proximal chamber with each beat. | 1+ | <20% |

| Moderate opacification of proximal chamber, clearing with subsequent beats. | 2+ | 21% to 40% |

| Intense opacification of proximal chamber, becoming equal to that of the distal chamber. | 3+ | 41% to 60% |

| Intense opacification of proximal chamber, becoming more dense than that of the distal chamber. Opacification often persists over the entire series of images obtained. | 4+ | >60% |

∗These regurgitant fraction values are dependent on numerous factors and should be taken only as rough estimates.

Modified from David CJ, Bonow RO: Cardiac Catheterization. In Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, p 458.

8. What is thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade?

TIMI flow grade is a system for qualitatively describing blood flow in a coronary artery. It was originally derived to describe blood flow down the infarct-related artery in patients with STEMI. Reportedly, it was originally written down on a napkin or the back of an envelope during an airplane flight. The grades are based on observing contrast flow down the coronary artery after injection of the contrast agent, and are as follows:

TIMI grade 3: normal contrast (blood) flows down the entire artery

TIMI grade 3: normal contrast (blood) flows down the entire artery

TIMI grade 2: contrast (blood) flows through the entire artery but at a delayed rate compared with flow in a normal (TIMI grade 3 flow) artery

TIMI grade 2: contrast (blood) flows through the entire artery but at a delayed rate compared with flow in a normal (TIMI grade 3 flow) artery

TIMI grade 1: contrast (blood) flows beyond the area of vessel occlusion but without perfusion of the distal coronary artery and coronary bed

TIMI grade 1: contrast (blood) flows beyond the area of vessel occlusion but without perfusion of the distal coronary artery and coronary bed

TIMI grade 0: complete occlusion of the infarct-related artery

TIMI grade 0: complete occlusion of the infarct-related artery

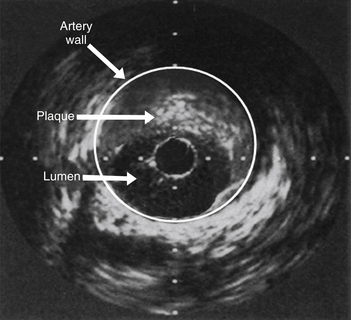

IVUS is the direct assessment of coronary arterial wall using a flexible catheter with a miniature ultrasound probe at its tip. Upon insertion into the coronary artery, IVUS provides true cross-sectional images of the vessel, delineating the three layers of the vessel wall (Fig 14-3). IVUS may aid in the assessment of coronary stenosis, plaque morphology, and optimal stent expansion when angiographic imaging is inadequate or indeterminate.

Figure 14-3 Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) demonstrating plaque occluding greater than 60% of the arterial lumen. Coronary angiography had demonstrated only mild narrowing in this segment of coronary artery.

10. What are the different methods of describing the aortic transvalvular gradient in a patient undergoing cardiac catheterization for the evaluation of aortic stenosis?

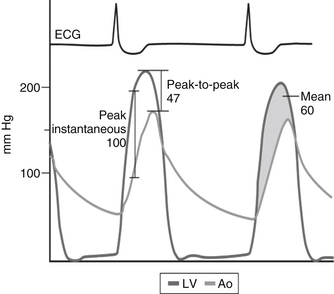

Three terms used to describe the gradient are illustrated in Figure 14-4 and are:

Figure 14-4 Various methods of describing the aortic transvalvular gradient. Ao, Aorta; ECG, electrocardiogram; LV, left ventricle. (From Bashore TM: Invasive cardiology: principles and techniques, Philadelphia, 1990, BC Decker, p 258.)

Peak instantaneous gradient: the maximal pressure difference between the left ventricular pressure and aortic pressure assessed at the exact same time

Peak instantaneous gradient: the maximal pressure difference between the left ventricular pressure and aortic pressure assessed at the exact same time

Peak-to-peak gradient: the difference between the maximal left ventricular pressure and the maximal aortic pressure

Peak-to-peak gradient: the difference between the maximal left ventricular pressure and the maximal aortic pressure

Mean gradient: the integral of the pressure difference between the left ventricle and the aorta during systole

Mean gradient: the integral of the pressure difference between the left ventricle and the aorta during systole

11. Which patients should be premedicated to prevent allergic reactions to iodine-based contrast agents?

12. What are the major risk factors for contrast nephropathy?

13. What are the major vascular complications with cardiac catheterization?

Retroperitoneal hematoma: This should be suspected in cases of flank, abdominal, or back pain, with unexplained hypotension, or with a marked decrease in hematocrit. Diagnosis is by computed tomography (CT) scan.

Retroperitoneal hematoma: This should be suspected in cases of flank, abdominal, or back pain, with unexplained hypotension, or with a marked decrease in hematocrit. Diagnosis is by computed tomography (CT) scan.

Pseudoaneurysm: A pseudoaneurysm results from the failure of the puncture site to seal properly. Pseudoaneurysm is a communication between the femoral artery and the overlying fibromuscular tissue, resulting in a blood-filled cavity. Pseudoaneurysm is suggested by the finding of groin tenderness, palpable pulsatile mass, or new bruit in the groin area. Pseudoaneurysm is diagnosed by Doppler flow imaging.

Pseudoaneurysm: A pseudoaneurysm results from the failure of the puncture site to seal properly. Pseudoaneurysm is a communication between the femoral artery and the overlying fibromuscular tissue, resulting in a blood-filled cavity. Pseudoaneurysm is suggested by the finding of groin tenderness, palpable pulsatile mass, or new bruit in the groin area. Pseudoaneurysm is diagnosed by Doppler flow imaging.

Arteriovenous (AV) fistula: An AV fistula can result from sheath-mediated communication between the femoral artery and the femoral vein. AV fistula is suggested by the presence of a systolic and diastolic bruit in the groin area. Diagnosis is confirmed by Doppler ultrasound.

Arteriovenous (AV) fistula: An AV fistula can result from sheath-mediated communication between the femoral artery and the femoral vein. AV fistula is suggested by the presence of a systolic and diastolic bruit in the groin area. Diagnosis is confirmed by Doppler ultrasound.

Stroke: Periprocedural stroke is a rare but morbid complication of cardiac catheterization, and is often associated with unfavorable neurologic outcome. A proportion of strokes may be due to disruption and embolization of atherosclerotic material from the aorta during the procedure.

Stroke: Periprocedural stroke is a rare but morbid complication of cardiac catheterization, and is often associated with unfavorable neurologic outcome. A proportion of strokes may be due to disruption and embolization of atherosclerotic material from the aorta during the procedure.

Cholesterol emboli syndrome: This is a rare and potentially catastrophic complication that results from plaque disruption in the aorta, with distal embolization into the kidneys, lower extremities, and other organs.

Cholesterol emboli syndrome: This is a rare and potentially catastrophic complication that results from plaque disruption in the aorta, with distal embolization into the kidneys, lower extremities, and other organs.

14. What are vascular closure devices?

15. What is the difference between radial and femoral access in cardiac catheterization?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Boudi, F.B. Coronary artery atherosclerosis. Available at www.emedicine.medscape.com. Accessed November 30, 2012

2. Carrozza JP: Complications of diagnostic cardiac catheterization. In Basow DS, editor: UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013, UpToDate. Available at: www.uptodate.com. Accessed March 26, 2013.

3. Levine, G.N., (chair)., Bates, E.R., Blankenship, J.C., et al. ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:2574–2609. 2011

4. Levine, G.N., Kern, M.J., Berger, P.B., et al. Management of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary revascularization. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:123–136.

5. Kern, M.J. The cardiac catheterization handbook, ed 4. St. Louis: Mosby; 2011.

6. Scanlon, P.J., Faxon, D.P., Audet, A.M., et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1756–1824.