Chapter 14. Cardiac arrest in adults

Advanced life support

The chances of surviving an out of hospital cardiac arrest are 1:100. The paramedic has two challenges:

1. To recognise and intervene appropriately in the care of the critically ill patient in order to prevent a cardiac arrest occurring

2. To respond promptly and skillfully to patients in cardiac arrest in order to optimise their chance of survival.

Defining cardiac arrest

• Cardiac arrest may be defined as the absence of a palpable pulse in an unresponsive patient. The pulse check is an unreliable sign if used in isolation from the clinical setting

• Lay rescuers are no longer taught to use a pulse check to verify cardiac arrest. Instead, they start chest compressions if there are no signs of circulation (such as normal breathing, coughing or movement)

• Paramedics should not rely solely on the pulse check to diagnose cardiac arrest, but should look for other indicators that the circulation has failed.

Cardiac arrest rhythms

Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring in cardiac arrest will establish the initial rhythm, which will be one the following:

• Obstructed airway

• Myocardial infarction, unstable angina

• Peri-arrest arrhythmia

• Status asthmaticus

• Status epilepticus

• Uncontrolled haemorrhage

• Anaphylaxis.

1. Ventricular fibrillation (VF)

2. Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT)

3. Asystole

4. Pulseless electrical activity (PEA).

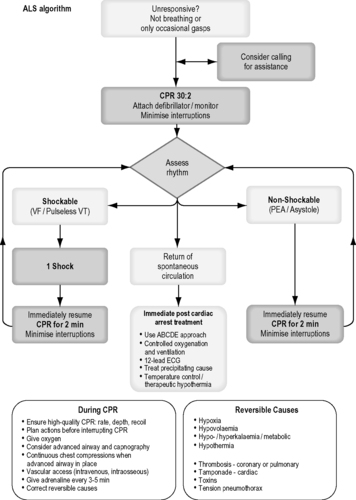

For treatment purposes, these rhythms are divided into:

• Shockable (VF/pulseless VT)

• Non-shockable (PEA or asystole).

The initial rhythm of a patient in cardiac arrest will determine which treatment algorithm is used first.

Chain of survival

The aim is a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Factors that are likely to result in a successful ROSC are:

1. Immediate basic life support including effective CPR. This means the patient stays in a shockable rhythm for longer

2. Fast defibrillation. Automatic external defibrillators are increasingly available in public areas for this reason

3. Early advanced life support. Successful intubation, oxygen and adrenaline will improve patient outcomes

4. Transfer to hospital. The underlying cause needs to be identified and treated.

The advanced life support approach

• SAFE approach

• Establish unresponsiveness

• Open the airway

|

| Figure 14.1. |

| The adult advanced life support algorithm (Resuscitation Council UK). The authors are aware of impending changes in resuscitation guidelines (late 2010). Refer to: www.resus.org.uk for further up-to-date information. |

• Assess breathing

• Attach monitor and assess the circulation.

Continue CPR with as few interruptions as possible. If good-quality bystander CPR is in progress, then encourage them to continue until the paramedic team is ready to take over. Apply defibrillating gel pads immediately to identify a shockable rhythm.

Once the patient is confirmed to be in cardiac arrest, he should be treated according to the initial rhythm.

Shockable (VF or pulseless VT)

Precordial thump

If a cardiac arrest is witnessed and monitored then a precordial thump may be administered. It should not delay, however, calling for help or accessing a defibrillator. This is equivalent to a low-energy defibrillatory shock and may revert a patient in the early stages of VF or VT to a perfusing rhythm. The thump should be given in the normal position for chest compression from a height of approximately 20 cm above the chest, using a closed fist.

Defibrillation

• VT without cardiac output will rapidly degenerate into ventricular fibrillation

• Defibrillation is the same for both conditions

• Success is greatest if a shock is applied within the first 90 seconds of the arrest

• Chances of successful defibrillation decline by about 10% per minute thereafter

• Single shocks are delivered and CPR is continued for 2 minutes. Only after one cycle (2 minutes) are checks made for a cardiac output. This is because even after successful defibrillation the heart will not function effectively for the first minute (myocardial stunning/cardiac standstill).

Adrenaline

• Adrenaline is the first-line drug in cardiac arrest in the UK. In cardiac arrest, its greatest effect is through peripheral vasoconstriction which raises the systemic vascular resistance, hence increasing cerebral and coronary perfusion during CPR

• When treating VF/VT cardia arrest, adrenaline 1 mg is given once chest compressions have restarted after the third shock

• 1 mg doses should be administered IV every other cycle (every 3–5 minutes), preferably not at the exact same time as a defibrillation shock

• Adrenaline can be administered by the intraosseous route if peripheral cannulation is unsuccessful

• Higher doses of adrenaline are not recommended.

Amiodarone

• If three unsuccessful shocks have been administered and the patient remains in VF or pulseless VT, then amiodarone should be given

• Amiodarone 300 mg IV bolus followed by a 20 ml IV flush whilst performing CPR

• A further dose of 150 mg IV can be given for recurrent or refractory VF/VT followed by an in-hospital infusion of 900 mg over 24 hours

• Do not abandon resuscitation in the face of VF/VT as these are potentially reversible.

Non-shockable (PEA/asystole)

The management of a PEA or asystolic cardiac arrest shifts from rapid defibrillation to undertaking good quality CPR, endotracheal intubation and intravenous adrenaline while seeking to identify and treat any reversible causes of the cardiac arrest. Adrenaline is administered every 3–5 minutes.

Pulseless electrical activity

• PEA may be defined as the presence of an ECG trace compatible with but not producing any detectable cardiac output

• Consider the four ‘Hs’ and the four ‘Ts’ (see below).

Asystole

• Asystole tends to be the terminal stage of primary cardiac arrest

• When asystole is secondary to other causes such as respiratory arrest or drug intoxication, the prognosis may be more favourable

• The diagnosis of asystole is confirmed by the presence of an almost flat ECG trace in a pulseless patient

• A rapid check must be made to confirm that:

1. The leads are connected correctly

2. The defibrillator is set to read through the leads

3. The chest electrodes remain attached

4. The amplitude setting (gain) on the monitor has not been set too low.

• Fine VF should be managed as for non-VF/VT. A shock is likely to be unsuccessful at this stage but good quality CPR may improve the amplitude of the ventricular fibrillation.

Reversible causes of cardiac arrest

There are a number of potentially reversible causes of cardiac arrest which should be excluded or identified whenever possible, especially in patients with non-VF/VT rhythms.

• These include the four ‘Hs’:

• Hypoxia

• Hypovolaemia

• Hypothermia

• Hypo/hyperkalaemia, hypocalcaemia, acidaemia, and other metabolic disorders

• and the four ‘Ts’:

• Tension pneumothorax

• Cardiac Tamponade

• Thromboembolics (pulmonary or coronary)

• Toxic (drug overdose or intoxication).

Resuscitation in special circumstances

Hypothermia

Severe hypothermia may cause significant bradycardia and reduced respiratory effort. Patients with a core temperature <30°C are unlikely to respond to defibrillation.

Distinguish patients in cardiac arrest due to hypothermia from those that have died and subsequently become cold. Do not declare hypothermic patients

Hypoxia

• Recognition: Obstructed airway, severe asthma, drowning

• Treatment: Endotracheal intubation and ventilation with high-concentration oxygen

Hypovolaemia

• Recognition: History/evidence of trauma, internal or external bleeding

• Treatment: Control external bleeding, fluid protocols for shock. Aggressive fluid therapy is likely to be needed

Tension pneumothorax

• Recognition: History of asthma or penetrating chest injury, high inflation pressures required to ventilate the patient, trachea deviated away from the pneumothorax, reduced breath sounds on the side of the pneumothorax

• Treatment: Needle thoracocentesis

Cardiac tamponade

• Recognition: penetrating chest injury, tension pneumothorax excluded, dilated neck veins

• Treatment: need a prehospital care team capable of performing open thoracotomy. Success only likely if within 10 min of the arrest.

dead on-scene but continue life support measures and convey them to hospital. If in doubt the paramedic should not withhold resuscitation.

Drowning

Cardiac arrest in drowning may be primary (e.g. secondary to an acute myocardial infarction causing ventricular fibrillation while swimming) or secondary (hypoxia from the submersion causing cardiac arrest). Attempts to retrieve the casualty from water must ensure that the rescuerhs personal safety is paramount.

There is a high incidence of spinal injury associated with drowning and appropriate steps to protect the spinal cord should be taken unless the history of the incident makes a spinal injury unlikely.

Treatment follows standard ALS protocols, but with increased emphasis on early ventilation and endotracheal intubation in order to correct hypoxia and protect the airway. Survival following prolonged immersion (>45 minutes) and resuscitation has been recorded and therefore attempts at resuscitation should not be abandoned in the prehospital environment.

Asthma

Cardiac arrest in asthma invariably arises due to hypoxia caused by severe bronchospasm and mucous plugging. Standard ALS algorithms should be followed with emphasis being placed on early intubation and ventilation.

Tension pneumothorax may be difficult to diagnose but should always be considered in the rapidly deteriorating asthmatic. The diagnosis is based on physical examination.

Pregnancy

Cardiac arrest during pregnancy is fortunately a rare event. Standard ALS protocols should be followed with the addition of manual displacement of the pregnant uterus to the left. Alternatively a wedge (pillows, blanket or rescuers’ thighs) should be placed under the patient’s right side in order to improve venous return.

The best chance for both the patient and the unborn baby is if an emergency caesarean section is undertaken within 5 minutes of the arrest, hence rapid transport to hospital is essential.

Anaphylaxis

Cardiac arrest due to anaphylaxis is usually caused by a combination of profound hypotension (secondary to vasodilation) and hypoxia due to acute airway obstruction and severe bronchospasm.

Resuscitation should aim to achieve early control of the airway and ventilation using a bag and mask followed by rapid intubation. Attempts at endotracheal intubation may fail due to upper airway swelling and if permitted, paramedics may need to consider an emergency needle cricothyroidotomy.

The circulation should be supported with a rapid infusion of intravenous fluids and adrenaline. Intravenous steroids and antihistamines may be given.

Trauma

Immediate cardiac arrest due to trauma is likely to be due to massive neurological or cardiac injury and is likely to be unsurvivable.

Cardiac arrest in the first few minutes may be due to a reversible cause such as hypovolaemia or tension pneumothorax. Massive external haemorrhage must be identified and stopped. Hypovolaemia is likely to result in PEA and may respond to fluid resuscitation.

Do not forget to protect the cervical spine where indicated.

Additional support

Consider requesting further support to the scene. A first responder or a second crew may be available. If another crew cannot be obtained, an Immediate Care doctor or nurse can be extremely helpful.

Paramedics will on occasion encounter doctors and other healthcare professionals at the scene of a cardiac arrest who may or may not be helpful. It can take confidence, tact and experience to reason with doctors and nurses, some of whom will have less up-to-date training in resuscitation.

While the doctor at the scene of a cardiac arrest will carry overall responsibility for any actions or omissions in their care of the patient, it may be necessary for paramedics to remind doctors of local resuscitation protocols.

Post-resuscitation care

If a return of spontaneous circulation is achieved then post-resuscitation care should be instituted. Warn the receiving hospital of your arrival.

On Scene

The following actions should be completed before leaving the scene:

• Airway: a patent airway must be established and high-flow oxygen administered

• Breathing: adequate respiratory effort and symmetrical chest movement must be ensured and air entry to both lungs and tracheal position checked. An SpO 2 monitor must be attached and the patient ventilated if he is in respiratory arrest. Titrate the inspired oxygen concentration to maintain between the range of 94–98%. Both hypo- and hyper-ventilation must be avoided. If available, an end-tidal CO 2 monitor is invaluable in confirming ET tube placement and to ensure normo-capnia.

En route to hospital

The following actions should be carried out en route to hospital:

• Circulation: cardiac monitoring must be continued and the blood pressure recorded. Intravenous access should be obtained if it is not already in place. Record a 12-lead ECG

• Disability: neurological status should be recorded using the AVPU score

• Environment: keep your patient warm and record a blood glucose level. Following ROSC, blood glucose should be maintained at ≤10 mmol L −1. Hypoglycaemia and strict blood glucose control should be avoided.

Ethical matters

Withholding CPR

• The paramedic’s safety is paramount in all resuscitation attempts. If it is not possible to make the scene safe then resuscitation should not be attempted until such time that additional help arrives and the scene is made safe

• There are a limited number of other occasions when it is considered inappropriate to commence resuscitation. These situations include those in which there is no possibility of survival such as when there is decapitation, rigor mortis, decomposition, incineration or massive cranial destruction

• Certain patients may have an active ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR) order or have an Advance Directive drawn up about their wishes, as those with malignant or end-stage disease

• These directives must be written (not verbal), be in-date and the paramedic must be confident that the documentation is valid and relates to the patient being treated and the circumstances have not changed. If there is any doubt then advanced life support should be started and the matter referred to hospital

• With the exception of the examples stated above, resuscitation should generally be started in all other cases of cardiac arrest. Judgements about the present or future quality of life made at the time of cardiac arrest are frequently inaccurate.

Discontinuing resuscitation efforts

The paramedic may consider discontinuing resuscitation in the presence of persistent asystole (longer than 20 minutes) provided that no exclusion criteria are present (children and young adults, pregnant females, electrocution, drowning, trauma, suspected hypothermia and overdose). Paramedics should be guided by their own local protocols in this regard.

If patients fall into the exclusion groups listed above, then they should be rapidly transported to hospital with ongoing attempts at resuscitation while en route.

If a patient remains in asystole after full advanced life support for 20 minutes, resuscitation may be discontinued provided that there are no signs of life:

1. No heart or breath sounds

2. No palpable pulse over 30 seconds

3. No movement or response to pain

4. Fixed and dilated pupils.

In these circumstances, a 30-second rhythm strip should be recorded and attached to the patient’s report form when confirming death.

Patient handover

• Advanced warning should be given to the receiving hospital that you will be arriving with a patient in cardiac arrest

• Consideration should be given to the essential information required by hospital staff. This includes:

1. Approximate time from collapse to arrival at scene (‘down-time’)

2. Administration and efficiency of any bystander CPR

3. Paramedic interventions so far (e.g. cannulation, defibrillation, intubation)

4. Any available medical history

5. Likely cause and any complications that have arisen

6. Response to resuscitative efforts.

For further information, see Ch. 14 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.