40 Cardiac Anesthesia

Training, Qualifications, Teaching, and Learning

Is cardiovascular disease (CVD) an issue that the anesthesiologist must be aware of, educated about, and qualified to deal with clinically? An obvious and resounding “yes” is the answer to this question. Anesthesiologists are confronted with the patient care dilemmas posed by the presence of CVD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis in an enormous number of patients spanning all age groups. Consider the following CVD statistics for the United States, as compiled and published in the American Heart Association’s Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2010 Update.1

Some 81.1 million Americans have one or more types of CVD; 38.1 million are estimated to be age 60 and older; one in three has CVD.1

With statistics such as those listed, there is quite a compelling argument that being aware of, educated about, and qualified to deal with patients with CVD is essential for all anesthesiologists. The complexity of cardiothoracic diseases requires that there be a cadre of specialty-educated cardiothoracic anesthesiologists who care for these high-acuity patients and educate residents and fellows about these special patients. The Anesthesiology Residency Review Committee (RRC) is quite clear about this in its statements defining faculty in the program requirements for graduate medical education (GME) in the core residency in anesthesiology and fellowship in adult cardiothoracic anesthesiology2,3:

Complementary to the above scholarship is the regular participation of the teaching staff in clinical discussions, rounds, journal clubs, and research conferences in a manner that promotes a spirit of inquiry and scholarship (e.g., the offering of guidance [mentoring] and technical support for fellows involved in research such as research design and statistical analysis); and the provision of support [mentoring] for fellows’ participation, as appropriate, in scholarly activities that pertain specifically to the care of cardiothoracic patients.2

It is these same specialists who conduct the basic science and clinical research that advances new knowledge and understanding of CVD and its anesthetic implications. What is the education available and required for cardiothoracic anesthesiologists?

Formalized education of cardiothoracic anesthesiologists

The continuum of education in anesthesiology is defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)2,3 and the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA).4 The continuum begins with an initial 4 years of postgraduate (post–medical school) education and constitutes the “core” anesthesiology residency.

The first year is a clinical nonanesthesiology (clinical base) year.

The clinical base year should provide the resident with 12 months of broad education in medical disciplines relevant to the practice of anesthesiology.2

The clinical base year must include at least six months of clinical rotations during which the resident has responsibility for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with a variety of medical and surgical problems, of which at most one month may involve the administration of anesthesia and one month of pain medicine. Acceptable clinical base experiences include training in internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery or any of their subspecialties, obstetrics and gynecology, neurology, family medicine or any combination of these as approved for residents by the directors of their training programs in anesthesiology. The clinical base year should also include rotations in critical care and emergency medicine, with at least one month, but no more than two months, devoted to each. Other rotations completing the 12 months of broad education should be relevant to the practice of anesthesiology.4

Clinical Anesthesia Years

The next 3 years are clinical anesthesiology years:

(2) Subspecialty anesthesia training is required to emphasize the theoretical background, subject material and practice of subdisciplines of anesthesiology. These subdisciplines include obstetric anesthesia, pediatric anesthesia, cardiothoracic anesthesia, neuroanesthesia, anesthesia for outpatient surgery, recovery room care, perioperative evaluation, regional anesthesia and pain medicine. It is recommended that these experiences be subspecialty rotations and occur in the CA-1 and CA-2 years. The sequencing of these rotations in the CA-1 and CA-2 years is left to the discretion of the program director.4

The ability to provide extensive specialized education in cardiac anesthesiology during the core residency is restricted primarily because of the time-limited nature of clinical anesthesia training, that is, a total of 36 months. The fundamental cardiac anesthesiology education commonly occurs during the CA-1 or CA-2 year.

The goals, timing, and minimum required perioperative clinical experiences in cardiothoracic anesthesiology include and are not limited to:

Patients who require specialized techniques for their perioperative care. There must be significant experience with a broad spectrum of airway management techniques (e.g., performance of fiberoptic intubation and lung isolation techniques such as double lumen endotracheal tube placement and endobronchial blockers). Residents also should have significant experience with central vein and pulmonary artery catheter placement and the use of transesophageal echocardiography.2

There is an opportunity for more extensive education about cardiac anesthesiology in the CA-3 year of the core residency:

Experience in advanced anesthesia training constitutes the CA-3 year. The program director, in collaboration with the resident, will design the resident’s CA-3 year of training. The CA-3 year is a distinctly different experience from the CA 1-2 years, requiring progressively more complex training experiences and increased independence and responsibility for the resident. Resident assignments in the CA-3 year should include the more difficult or complex anesthetic procedures and care of the most seriously ill patients.2

More extensive education about cardiac anesthesiology in the CA-3 year would be most appropriate for those practitioners electing to subspecialize; however, the CA-3, 6-month subspecialty education option is out of vogue. In 1988–1989, the ABA extended the core anesthesiology residency to a required CA-3 year. In 1989–1990, 56% (606/1084) of CA-3 residents elected more than 6 months of subspecialty training (all anesthesiology subspecialties are represented in this composite number).5,6 By 1993–1994, only 29%, by 1995–1996, only 21%, and by 2000–2001, a mere 6% (66/1043) elected more than 6 months of subspecialty training in the CA-3 year.5,6

At the same time that CA-3 subspecialty education was becoming rare, the absolute number and percentage of total CA-4 residents who electively enrolled in a 12-month postresidency fellowship program increased (1989–1990: 63/105 [60%]; 1998–1999: 523/605 [86%]; and 2000–2001: 383/525 [73%] CA-4 residents enrolled in a 12-month subspecialty fellowship).5,6

It is quite apparent from the residency curriculum outlined earlier that a graduating core resident will most likely be, at best, modestly educated as a specialist cardiac anesthesiologist. More complete subspecialty education is provided through a fellowship (minimum 1-year clinical GME program) that follows the core residency. Over the years, a significant number of individuals have elected CA-4 cardiac anesthesiology subspecialty fellowship education (in 2000–2001, 69 of 383 [18%] CA-4 residents selected cardiac anesthesiology as their fellowship track).5 This blends well with the fact that many other medical, surgical, and diagnostic disciplines offer accredited fellowship education to develop so-called subspecialists in their respective specialties. Accredited subspecialty graduate education programs of a year or more in duration exist in anesthesiology and medical, pediatric, surgical, and diagnostic disciplines related to cardiac anesthesiology7 (Table 40-1).

TABLE 40-1 Number of Resident Physicians (Fellows) on Duty December 1, 2008 in Selected Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited Subspecialty and Combined Specialty Graduate Medical Education Programs Related to Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology (Anesthesiology Subspecialty Programs for Comparison)7

| Specialty/Subspecialty | No. of Programs | No. of Fellows |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 180 | 2434 |

| Clinical cardiac electrophysiology | 96 | 155 |

| Critical care medicine | 32 | 136 |

| Pulmonary disease | 22 | 81 |

| Pulmonary disease and critical care medicine | 133 | 1266 |

| Pediatrics | ||

| Pediatric cardiology | 48 | 336 |

| Pediatric critical care medicine | 61 | 357 |

| Pediatric pulmonary | 47 | 125 |

| Radiology-diagnostic | ||

| Cardiothoracic radiology | 2 | 2 |

| Vascular and interventional radiology | 93 | 148 |

| Surgery | ||

| Surgical critical care | 94 | 153 |

| Thoracic surgery | 76 | 230 |

| Congenital cardiac surgery | 6 | 2 |

| Subtotal | 890 | 5425 |

| Anesthesiology | ||

| Adult cardiothoracic anesthesiology | 44 | 86 |

| Critical care medicine | 47 | 81 |

| Pediatric anesthesiology | 45 | 129 |

| Total | 8694 | 11,146 |

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists (SCA) championed a different viewpoint.8 The SCA reasoned that, although it is true that all anesthesiologists care for patients with cardiac disease, there has developed, since the 1980s, a highly sophisticated knowledge base (e.g., physiology of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, clinical management of anticoagulation, anesthetic management of patients undergoing electrophysiologic diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and physiologic management of mechanical assist devices bridging to heart and lung transplantation) and a technically demanding set of psychomotor skills (e.g., pulmonary artery catheterization, intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation, and transesophageal echocardiography [TEE]) that enable the safe and effective care of patients with very-high-acuity CVD.

Cardiothoracic anesthesiology has blossomed into a subdiscipline that exists adjunctively to the core discipline of anesthesiology. More than 6000 anesthesiologists (approximately 14% of the total American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] membership) are SCA members identifying themselves as individuals who recognize that cardiac anesthesiology constitutes more than the basic discipline of anesthesiology. Scientific and educational meetings to disseminate this subspecialty knowledge and develop practice protocols, research programs, and projects devoted specifically to cardiac anesthesiology exist to serve the needs of these subspecialists.8

The SCA believes that only through concentrated full immersion in a minimum 1-year clinical fellowship devoted exclusively to cardiothoracic anesthesiology will an anesthesiologist be able to gain sufficient and sophisticated enough knowledge and skill to be a subspecialist able to care for patients with very-high-acuity CVD. In similar fashion, it will only be through accredited fellowship education that subspecialists in cardiac anesthesiology will be on par with the large number of fellowship-educated cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, and all other medical, pediatric, surgical, and diagnostic subspecialists who care for patients with CVD (see Table 40-1).

In 2006, the ACGME, through the sponsorship of the Anesthesiology RRC, established program requirements for standardized adult cardiothoracic anesthesiology fellowship education as had been recommended by the SCA3 (see Appendix 40-1). The recommended essential ingredients of clinical cardiothoracic anesthesiology fellowship education are a minimum one-year time frame during which an exhaustive list of didactic topics for study is coupled with mastery of a much more inclusive set of psychomotor skills (including Basic and Advanced Perioperative Echocardiograph (see Chapter 41) than that which is required for core resident education.3

Qualifications of cardiothoracic anesthesiologists

Accreditation

The “ACGME is responsible for the accreditation of post-MD medical training programs within the United States. Accreditation is accomplished through a peer review process and is based upon established standards and guidelines.”9

The mission of the ACGME is to improve the quality of health in the United States by ensuring and improving the quality of graduate medical education experience for the physicians in training. The ACGME establishes national standards for graduate medical education by which it approves and continually assesses educational programs under its aegis. It uses the most effective methods available to evaluate the quality of graduate medical education programs. It strives to develop evaluation methods and processes that are valid, fair, open and ethical.10

GME programs voluntarily apply for accredited status and agree to meet the defined program requirements and undergo periodic scrutiny to document compliance. Accredited status brings with it public recognition and the benefits of being subject to specialty-specific and general institutional ACGME standards. As an example of such a benefit, common program requirements that provide a “level playing field” for all GME programs have been published by the ACGME.11

In 2006, the ACGME, through the sponsorship of the Anesthesiology RRC, established program requirements for standardized adult cardiothoracic anesthesiology fellowship education as had been recommended by the SCA (see Appendix 40-1).3

Certification

A physician who successfully completes an accredited fellowship program may voluntarily apply to become identified as a board-certified specialist. Board certification is under the auspices of the American Board of Medical Specialties:

The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) is an organization of 24 approved medical specialty boards. The intent of the certification of physicians is to provide assurance to the public that those certified by an ABMS Member Board have successfully completed an approved training program and an evaluation process assessing their ability to provide quality patient care in the specialty.12

An increasing amount of scientific evidence exists that attests to the fact that board certification status relates directly to better patient outcome. Silber et al’s13–15 studies, in particular, suggest that quality of patient care improves when anesthesiologists are board certified. Brennan et al16 provide considerable evidence making the case for viewing certification status as an evidence-based quality measure.

The ABMS serves to coordinate the activities of its Member Boards and to provide information to others concerning issues involving specialization and certification of medical specialists.12 The ABA is one of the ABMS Member Boards.

Because of the nature of anesthesiology, the ABA Diplomate must be able to manage emergent life threatening situations in an independent and timely fashion. The ability to independently acquire and process information in a timely manner is central to assure individual responsibility for all aspects of anesthesiology care. Adequate physical and sensory faculties, such as eyesight, hearing, speech and coordinated function of the extremities, are essential to the independent performance of the Board certified Anesthesiologist. Freedom from the influence of or dependency on chemical substances that impair cognitive, physical, sensory or motor function also is an essential characteristic of the Board certified anesthesiologist.4

Board certification in cardiac anesthesiology does not currently exist in the United States.

Credentialing and Clinical Privileges

Anesthesiologists may practice as cardiac subspecialists even though board certification does not exist in the United States. Hospital medical staffs have the privilege and obligation to define what physicians can and cannot do with respect to patient care in their institution. This process is medical credentialing.

To be awarded medical staff privileges in anesthesiology, a physician must fully meet certain required criteria. It is possible to make all the following criteria mandatory or to have a mixture of required and optional criteria. Organizations [Hospital Medical Staffs] should determine which criteria to include and whether to include additional criteria based on the institution’s individual requirements and preferences. For example, some facilities may decide that certification by the [ABA] is a requirement for clinical privileges in anesthesiology, while others may deem board certification to be desirable but not essential. Similarly, some institutions may decide that subspecialty fellowship training is needed for certain clinical privileges, while others may not. Some organizations may wish to recognize residency training obtained or certification awarded outside the United States. Institutions granting subspecialty clinical privileges may wish to recognize experience as an alternative to formal training in a subspecialty of anesthesiology. Some institutions may wish to modify certain requirements for physicians who have recently completed their residency or fellowship training.17

The ASA has published guidelines for delineating clinical privileges in anesthesiology taking into consideration educational, licensure, performance improvement, personal qualifications, and practice pattern criteria.17 Many physicians are recognized as credentialed cardiac anesthesiologists and are granted specific clinical privileges defined by their practice group and hospital medical staff while at the same time they are not certified by the ABA. These cardiac anesthesiologists are “experts” in their subspecialty and clearly qualified to care for patients with CVD.

Teaching and learning cardiac anesthesiology

Teachers and the Teaching/Learning Environment

Teaching and learning cardiac anesthesiology best takes place in an environment conducive to the educational process with a set of goals and objectives to guide the endeavor. This has been defined by the Anesthesiology RRC in their program requirements for GME in adult cardiothoracic anesthesiology (see Appendix 40-1).3

Systems-based practice, as manifested by actions that demonstrate an awareness of and responsiveness to the larger context and system of health care, as well as the ability to call effectively on other resources in the system to provide optimal health care.3

A key factor for successful education is the commitment of effective teachers. A description of the effective clinical teacher has been put forth that, although written about the internal medicine teaching setting, is applicable to all disciplines and certainly cardiothoracic anesthesiology.18 Effective teachers demonstrate, among other traits, the characteristics outlined in Box 40-1.18 Effective teachers are also role-models and teach professionalism.19

BOX 40-1. Characteristics of an Effective Clinical Teacher18

Curriculum

The cognitive or knowledge base of cardiothoracic anesthesiology is readily recognized as the basic medical sciences applied clinically. Cardiac embryology, histology, and gross anatomy; cardiorespiratory physiology; and adrenergic, anticoagulation, and antiarrhythmic pharmacology and pathophysiology of cardiac valve disorders are examples of some of the required cognitive base of cardiothoracic anesthesiology. An expansive topical content of cardiothoracic anesthesiology is listed in the ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Adult Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology (see Appendix 40-1).3

The didactic curriculum provided through lectures, conferences, and workshops should supplement clinical experience as necessary for the fellow to acquire the knowledge to care for adult cardiothoracic patients and meet the conditions outlined in the guidelines for the minimum clinical experience for each fellow.3

Complete cognitive learning is a process whereby the facts are considered in a variety of ways that take them beyond simple uninterpreted and unapplied statements. Teaching in the content area requires attention to increasingly complex cognitive functions described by Bloom20 (Box 40-2).

BOX 40-2. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Learning Outlining a Hierarchy From Simple (Knowledge) to Complex (Evaluation) Processes20

Bloom’s taxonomy fits well with the ABA oral examination process that is designed “to assess the candidate’s ability to demonstrate the attributes of an ABA Diplomate [understand and apply complex cognitive functions] when managing patients presented in clinical scenarios. The attributes are (a) appropriate application of scientific principles to clinical problems, (b) sound judgment in decision-making and management of surgical and anesthetic complications, (c) adaptability to unexpected changes in the clinical situations, and (d) logical organization and effective presentation of information. The oral examination emphasizes the scientific rationale underlying clinical management decisions”21 (Box 40-3).

BOX 40-3. Attributes of an American Board of Anesthesiology Diplomate to be Evaluated During the Oral Examination and Not By the Written Examination21

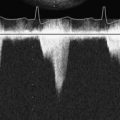

Although much of medical knowledge is broadly applicable to a wide variety of specialties, psychomotor learning is often quite specific to the specialty in question. Psychomotor skills that must be learned by the cardiac anesthesiologist, for example, do not apply at all to the dermatologist. Bedside cardiac catheterization with the balloon flotation pulmonary artery catheter, administration of carefully titrated vasoactive infusions, manipulation of cardiac output using the intra-aortic balloon pump, and TEE are examples of the required psychomotor skills of cardiothoracic anesthesiology. TEE is a prime example of a psychomotor skill set that, once learned, distinguishes the cardiac anesthesiologist from all other anesthesiologists unskilled in this technique. (See Chapter 41 for educational principles related to mastery of perioperative TEE.)

The psychomotor skill lesson is vital to effective learning in cardiothoracic anesthesiology. Cardiac anesthesiology psychomotor techniques such as internal jugular catheterization and fiberoptic bronchoscopy are most effectively and efficiently taught with less potential harm to patients when using a systematically applied skill lesson plan.

Developing a psychomotor skill lesson is an example of how understanding instructional methodology can lead to effective teaching and learning. The old adage about teaching psychomotor skills in medicine is “see one, do one, teach one.” The absurd nature of this approach has been highlighted in the following way: “This is akin to a piano instructor playing ‘The Minute Waltz’ for a beginner and then saying, ‘Now, try it yourself.’”22,23

Rather than the repetitive trial-and-error approach to teaching/learning psychomotor skills, a systemic methodology can be used23 (Box 40-4).

BOX 40-4. Systematic Methodology For Psychomotor Skill Lessons22,23

Affective teaching and learning is perhaps the least understood and most underappreciated of the categories of curricular material. Affective teaching/learning deals with feelings or emotions. The taxonomy of affective learning addresses the following22,24: Receiving, Responding, Valuing, Organizing, Value Complexing. Although anesthesiologists actively and consciously teach in the cognitive and psychomotor areas, they are much less aware of their affective teaching. Even though clinicians may not be aware of it, they are constantly teaching in the affective arena by the role modeling performed…an example of how affective teaching and learning takes place [is] described.22

In the real-life setting, the aggressive, passive-aggressive, or passive posture of the anesthesiology teacher interacting with the surgeon provides a lasting lesson in the affective domain for the resident [fellow] anesthesiology learner.22 Simulation may be the educational solution to issues described in the psychomotor and affective learning scenarios (see later).

Teaching process and content resources

Print materials (textbooks and journals) offering information about cardiothoracic anesthesiology and its related subjects are so numerous and constantly being updated and added to that it is impossible to have a current, complete, and comprehensive library. The Internet solves the problem of constantly being out-of-date with one’s print library. The Internet has opened up the teaching environment to an enormous wealth of didactic and interactive teaching materials. Search engines, databases, and Internet links make an encyclopedic amount of up-to-date information available to the learner in cardiothoracic anesthesiology. Utilization of these web resources gives the cardiothoracic anesthesiology fellow access to learning materials and teaching methods that she or he might never have known existed. In addition, using Web-based resources reduces the need for the cardiothoracic anesthesiology fellow to “reinvent the wheel,” as she or he can take advantage of what others have already discovered and “published” on the Internet. Appendix 40-2 offers a catalogue of cardiothoracic anesthesiology Web-based resources. Although it would be nice to state that this catalogue is all-inclusive, by its very nature, the Internet is never exhausted and more cardiothoracic anesthesiology Web-based resources exist and will be listed in the future. The cardiothoracic anesthesiology student and practitioner are encouraged to use the Web-based resource listing as a springboard to continually explore this vast educational reservoir as a lifelong learning exercise.

Simulation

Atul Gawande has made a critically important medical education dichotomy and dilemma transparent to the public in his book Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science in the chapter entitled “Education of a Knife.” Gawande25 writes that there is an “imperative to give patients the best possible care and [at the same time] to provide novices with experience [education is change in behavior based on experience(s)].” To accomplish these two conflicting imperatives in the past, learning clinical care (e.g., cardiac anesthesia) was most often a process of application of knowledge and trial of techniques, both new to the student, on high-acuity/low-physiologic reserve patients in real-time patient care settings. This scenario was characterized by high anxiety for the student and significant risk for complications to the patient cared for by the novice. For the present and future, Gawande25 makes it clear that the traditional medical education paradigm is no longer acceptable: “By traditional ethics and public insistence (not to mention court rulings), a patient’s right to the best care possible must trump the objective of training novices.”

The aviation industry long ago recognized this dilemma when teaching pilots. Acknowledging the high-stakes nature of flying, simulation technology was instituted to teach and evaluate a pilot’s competence rather than allow her or him to fly a jumbo jet and risk loss of hundreds of lives. Learning to apply the knowledge and perform the techniques before entering the “cockpit” reduces the risk for a “crash disaster.” Medical care in general and anesthesia patient care in particular, especially of very-high-risk patients with CVD, is analogous to the jumbo jet situation and logically calls for a similar approach to education, that is, use of simulation.26 The public is no longer willing to accept teaching on patients. In the cardiothoracic patient care arena, for example, education has moved to virtual reality training for cardiac operating room and catheterization procedures.27

Imitation of a real-life clinical situation, using stand-in devices that assume the patient role, provides learner experience while permitting teaching and learning in repetitive fashion with zero risk to both the provider and recipient of the simulated care.28 An exponential growth of simulation devices has occurred in medicine over the past several decades, many of which are directly applicable to education of cardiothoracic anesthesiologists. Flat-screen computer and mannequin-based simulators have been developed to mimic many patient care settings. Examples of relatively high-fidelity high-technology simulators especially pertinent to learning cardiothoracic anesthesiology include “Harvey,” the cardiology patient simulator,29–31 multimedia computer-assisted cardiology simulation,32 anesthesia simulators,33–35 and bronchoscopy simulators.36 Evidence has been accumulated that simulation results in a better educational outcome for the learner. Schwid and colleagues37 randomized anesthesiology residents and faculty into two learning groups (textbook reading vs. computerized ACLS [Advanced Cardiac Life Support] simulation education) preparing for performance evaluation at an ACLS mock resuscitation. Computer simulation–prepared learners were judged to perform better than textbook-prepared learners during standardized mega codes that required treatment protocols for clinical simulation of cardiovascular life-threatening scenarios with supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and second-degree type II atrioventricular block.37 Pulmonary artery catheterization and cardiovascular physiologic management can be effectively presented through a computer-based critical care training simulation.38

Simulation adds other, more sophisticated aspects to education that are not possible from traditional textbook learning, classroom lectures, or single-learner computer-based programs. These missing ingredients are teamwork and improved processes of care. Multidiscipline teams working effectively together must develop if the best medical care is to be provided to patients. Aviation’s crew resource management (CRM) concepts can be effectively taught through group simulation exercises.39 The potential for CRM teaching to positively impact care of patients with CVD is enormous when the team of cardiac anesthesiologists is educated with others who care for the same patients, including cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, cardiac operating room nurses, perfusionists, and respiratory therapists. Holzman and colleagues40 and Grogan and colleagues39 have demonstrated that CRM (also called anesthesia crisis resource management [ACRM]) enhances (1) interpersonal communication, situational awareness, and appropriate management of available patient care resources40; and (2) fatigue management, adverse event recognition, team decision making, and performance feedback.39 CRM is so timely a topic that an entire supplement issue of Quality & Safety in Health Care entitled “Simulation and Team Training” described the state of the art.41

Although improved patient outcome from simulation education is intuitively obvious, scant evidence-based medicine exists to prove this. Sedlack and colleagues,42 for example, have demonstrated that patients reported more comfort, a direct benefit to the patient, during gastrointestinal endoscopy provided by computer-based, simulation-trained endoscopists than when the same procedure was performed by patient-based trained endoscopists. Combing the literature for similar studies that document “direct patient benefit” and “improved patient outcome” related to simulation education of anesthesiologists results in virtually nothing of scientific significance. However, studies do document the educational benefit of simulation technology.43 The clear challenge is to devise methods to scientifically prove that simulation education does benefit patients.

Evaluation

Resident/Fellow Evaluation

The Anesthesiology RRC and the ABA outline the process for evaluation of the resident and fellow.2–4

Formative Evaluation [see Appendix 40-1 for complete requirements of formative evaluation]

Lifelong learning, continuing medical education, and maintenance of certification

The American Medical Association definition of CME is as follows:

CME consists of educational activities which serve to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance and relationships that a physician uses to provide services for patients, the public or the profession. The content of CME is the body of knowledge and skills generally recognized and accepted by the profession as within the basic medical sciences, the discipline of clinical medicine, and the provision of health care to the public [AMA House of Delegates policy #300.988].44

Continued physician licensure, hospital/medical staff appointment, and maintenance of board certification status require documentation of lifelong learning and participation in accredited CME activities. Since January 1, 2000, the ABA issues 10-year time-limited certificates. Anesthesiologists wishing to renew their board certification status will have to complete the 10-year Maintenance of Certification Process in Anesthesiology (MOCA).45 The MOCA process serves as the formal mechanism for recertification of board certification status and its principles serve as a lifelong learning process for cardiothoracic anesthesiologists.

Summary

The following practical advice on learning cardiothoracic anesthesia includes pearls to consider.46

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Adult Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology3

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Cardiac Anesthesiology Web-Based Resources

Specialty Societies

Educational Resource Sites

Practice Guidelines and Advisories

ASA Practice Parameters: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/c-4-practice-parameters.aspx

Practice Guidelines for Pulmonary Artery Catheterization: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-179-practice-guidelines-for-pulmonary-artery-catheterization.aspx

Practice Guidelines for Perioperative Transesophageal Echocardiography: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-351-practice-guidelines-for-perioperative-transesophageal-echocardiography.aspx

Practice Guidelines for Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-116-practice-guidelines-for-perioperative-blood-transfusion-and-adjuvant-therapies.aspx

Perioperative Management of Patients with Cardiac Rhythm Management Devices: Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-114-perioperative-mgmt-of-patients-with-cardiac-rhythm-mgmt-devices-pacemakers-and-implantable-cardioverter-defibrillators.aspx

Practice Alert for the Perioperative Management of Patients with Coronary Artery Stents: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-323-practice-alert-for-the-perioperative-management-of-patients-with-coronary-artery-stents.aspx

Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway: https://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-177-practice-guidelines-for-management-of-the-difficult-airway.aspx

Research Resource Sites

1 American Heart Association, Heart disease and stroke statistics, Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1265665152970DS-3241%20HeartStrokeUpdate_2010.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2010

2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ACGME Anesthesiology program requirements, Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/040pr703_u804.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2010

3 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, ACGME Adult Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology program requirements, Available at: http://acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/041pr206.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2010

4 American Board of Anesthesiology, Certification and Maintenance of Certification, February 2001. Available at: http://viewer.zmags.com/publication/8418a33c#/8418a33c/1. Accessed February 23, 2010

5 Reves J.G. Resident subspecialty training. Park Ridge, IL: ASA, 2000–2001. (Section on Representation)

6 Havidich J.E., Haynes G.R., Reves J.G. The effect of lengthening anesthesiology residency on subspecialty education. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:844.

7 Appendix II: Graduate medical education, 2008-2009. JAMA. 2009;302:1357.

8 Available at: http://www.scahq.org/sca3/fellowships/Criteria_for_Recognition-2004.pdf. Accessed December 7, 2004

9 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp. Accessed February 28, 2010

10 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, The purpose of accreditation; February 28, 2010; Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/about/ab_purposeAccred.asp. Accessed

11 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/dutyHours/dh_dutyhoursCommonPR07012007.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2010

12 American Board of Medical Specialties, Available at: http://www.abms.org/. Accessed February 28, 2010

13 Silber J.H., Williams S.V., Krakauer H., et al. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30:615.

14 Silber J.H., Kennedy S.K., Even-Shoshan O., et al. Anesthesiologist direction and patient outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:152.

15 Silber J.H., Kennedy S.K., Even-Shoshan O., et al. Anesthesiologist board certification and patient outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1044.

16 Brennan T.A., Horwitz R.I., Duffy F.D., et al. The role of physician specialty board certification status in the quality movement. JAMA. 2004;292:1038.

17 , Guidelines for delineation of clinical privileges in anesthesiology, Available at: http://www.asahg.org/For_Healthcare_Professionals/Standards_Guidelines_and_Statements.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2010

18 Mattern W.D., Weinholtz D., Friedman C.P. The attending physician as teacher. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1129.

19 Gaiser R.R. The teaching of professionalism during residency: Why it is failing and a suggestion to improve its success. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:948.

20 Bloom B.S., editor. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay, 1956.

21 American Board of Anesthesiology, An overview of the certification process with emphasis on the oral examination, Available at: http://www.theaba.org/pdf/oral-overview.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2010

22 Schwartz A.J. Teaching anesthesiology. In: Miller R.D., editor. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010:193-207.

23 Foley R.P., Smilansky. Teaching Techniques. A Handbook for Health Professionals. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980.

24 Krathwohl D.R., Bloom B.S., Masia B.B. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Handbook. II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay, 1964.

25 Gawande A. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002;11-34.

26 Issenberg S.B., McGaghie W.C., Hart I.R., et al. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. JAMA. 1999;282:861.

27 Gallagher A.G., Cates C.U. Virtual reality for the operating room and cardiac catheterisation laboratory. Lancet. 2004;364:1538.

28 Friedrich M.J. Practice makes perfect: Risk-free medical training with patient simulators. JAMA. 2002;288:2808.

29 Gordon M.S., Ewy G.A., Felner J.M., et al. Teaching bedside cardiologic examination skills using “Harvey,” the cardiology patient simulator. Med Clin North Am. 1980;64:305.

30 Sajid A.W., Ewy G.A., Felner J.M., et al. Cardiology patient simulator and computer-assisted instruction technologies in bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1990;24:512.

31 Jones J.S., Hunt S.J., Carlson S.A., et al. Assessing bedside cardiologic examination skills using “Harvey,” a cardiology patient simulator. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:980.

32 Waugh R.A., Mayer J.W., Ewy G.A., et al. Multimedia computer-assisted instruction in cardiology. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:197.

33 Euliano T., Good M.L. Simulator training in anesthesia growing rapidly. J Clin Monit. 1997;13:53.

34 Good M.L. Patient simulation for training basic and advanced clinical skills. Med Educ. 2003;37(Suppl 1):14.

35 Murray D.J., Boulet J.R., Kras J.F., et al. Acute care skills in anesthesia practice: A simulation-based resident performance assessment. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1084.

36 Blum M.G., Powers T.W., Sundaresan S. Bronchoscopy simulator effectively prepares junior residents to competently perform basic clinical bronchoscopy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:287.

37 Schwid H.A., Rooke G.A., Ross B.K., et al. Use of a computerized advanced cardiac life support simulator improves retention of advanced cardiac life support guidelines better than a textbook review. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:821.

38 Saliterman S.S. A computerized simulator for critical-care training: New technology for medical education. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:968.

39 Grogan E.L., Stiles R.A., France D.J., et al. The impact of aviation-based teamwork training on the attitudes of health-care professionals. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:843.

40 Holzman R.S., Cooper J.B., Gaba D.M., et al. Anesthesia crisis resource management: Real-life simulation training in operating room crises. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:675.

41 Henriksen K. Simulation and team training. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i1.

42 Sedlack R.E., Kolars J.C., Alexander J.A. Computer simulation training enhances patient comfort during endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:348.

43 Schwid H.A., Rooke A., Carline J., et al. Evaluation of anesthesia residents using mannequin-based simulation. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1434.

44 American Medical Association, The Physician’s Recognition Award and Credit System: The AMA definition of CME, Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/455/pra2006.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2010

45 American Board of Anesthesiology, Maintenance of certification frequently asked questions, Available at: http://www.theaba.org/FAQ/moc. Accessed March 2, 2010

46 Schwartz A.J. Learning cardiothoracic anesthesia. In: Thys D.M., editor. Textbook of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:11-23.

Barrows H.S. Simulated (Standardized) Patients and Other Human Simulations. Chapel Hill, NC: Health Sciences Consortium, 1987.

Bunker J.P., editor. Education in Anesthesiology. New York: Columbia University Press, 1967.

Chin C., Schwartz A.J. Teaching Pediatric Cardiac Anesthesiology. In: Lake C.L., Booker P.D., editors. Pediatric Cardiac Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:755-765.

Comroe J.H. Exploring the heart. In: Discoveries in Heart Disease and High Blood Pressure. New York: WW Norton; 1983.

Jason H., Westberg J. Instructional Decision-Making Self-Study Modules for Teachers in the Health Professions (Preview Package). Miami, FL: University of Miami School of Medicine, 1980. National Center for Faculty Development.

Lear E., editor, Virtual reality in patient simulators Am Soc Anesthesiol Newsletter; 61; 1997; (October)

Lyman R.A. Disaster in pedagogy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:504.

McCauley K.M., Brest A. McGoon’s Cardiac Surgery: An Interprofessional Approach to Patient Care. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1985.

Miller G.E. Adventure in pedagogy. JAMA. 1956;162:1448.

Miller G.E. Educating Medical Teachers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Schwartz A.J. Teaching and learning congenital cardiac anesthesia. In: Andropoulos D.B., Stayer S.A., Russell L.A., editors. Anesthesia for Congenital Heart Disease. Armonk, NY: Futura, 2005.