Cardiac Anatomy

Christopher J. Gallagher and John C. Sciarra

Imaging Planes

Time to go back to the model and the pie-shaped slice of imaging that comes out of the echo probe.

And time to take another good look at a plastic model of a heart.

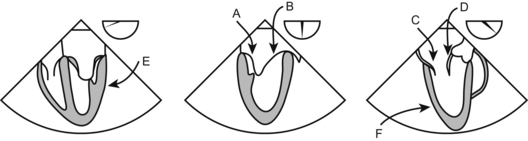

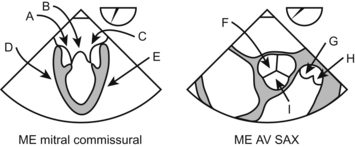

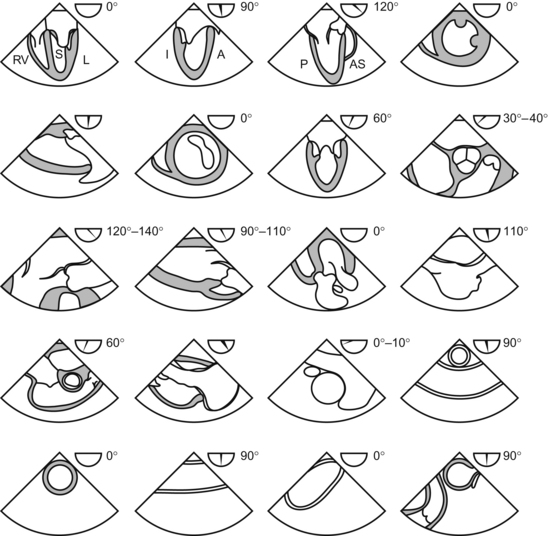

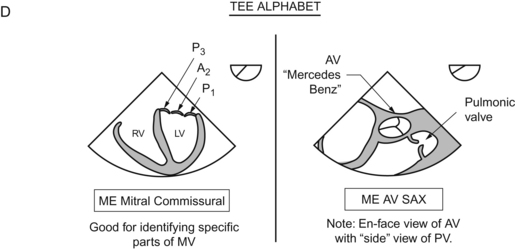

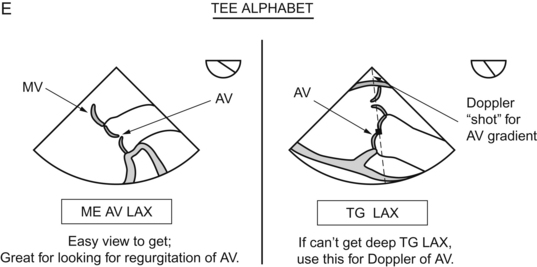

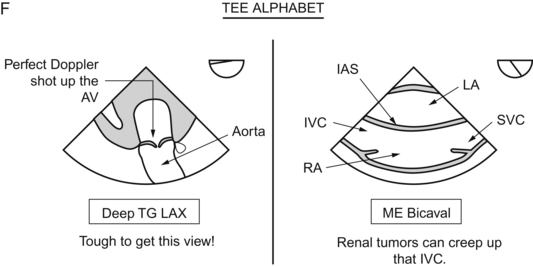

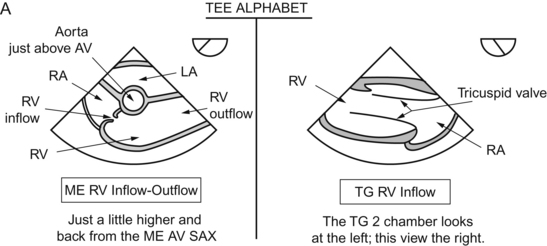

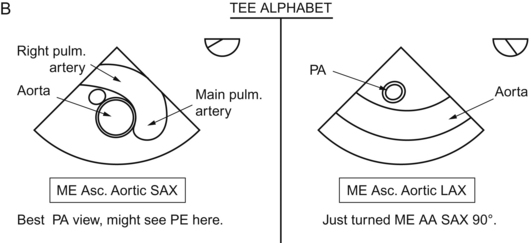

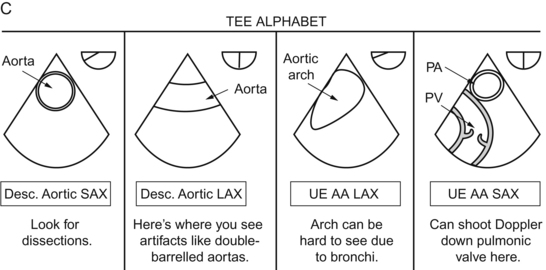

These imaging planes tie in with the BIG 20 views of the heart. These are the 20 views detailed in THE ARTICLE by Shanewise et al on echo.1 The 20 views are also detailed a million times over on different internet sites. Google “University of Toronto: TEE” for a great tutorial. This article and the 20 views detailed therein are the absolute crux of the TEE experience. Photocopy those 20 views and tape them to your TEE machine. Every time you examine a patient, try to get all the 20 views. Get in the habit of “examining everything every time”. If not, you’ll just look at the “thing of interest” and you’ll miss something else.

Shanewise has thrown down the gauntlet. Can you do it that fast?

In each view, note the approximate omniplane angle!

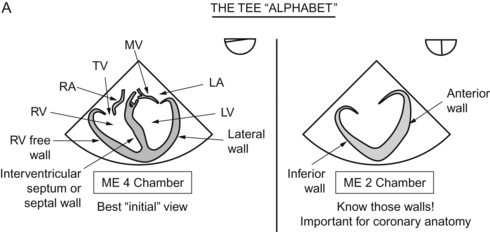

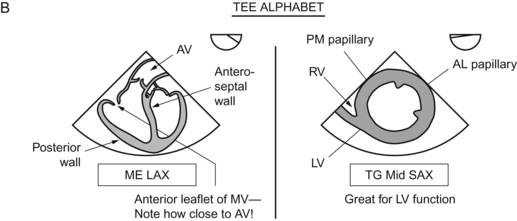

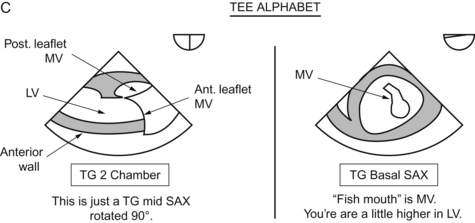

Cardiac Chambers and Walls

As time passes, you’ll get to know what each view can “do” for you.

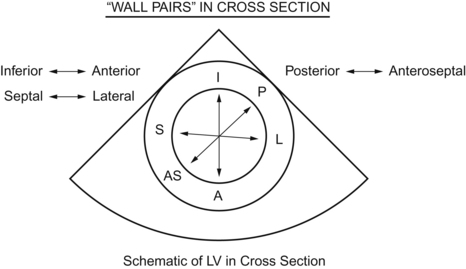

Now go transgastric, and you see all this stuff in cross section.

Need a little crutch? Try this. Draw a cross section first and get those walls down. Then, draw lines connecting each to its opposite wall. That will get you to link these walls in pairs and keep you from getting mixed up.

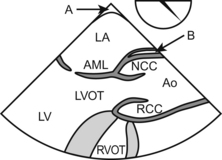

Cardiac Valves

Back to Med School for a minute.

The mitral valve is between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

The aortic valve is between the left ventricle and the aorta.

The tricuspid valve is between the right atrium and the right ventricle.

The pulmonic valve is between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery.

All valves have three leaflets except the mitral valve, which has two.

It is comforting to know that there is nothing we are incapable of forgetting.

Cardiac Cycle and Relation of Events Relative to ECG

Break it down into sections. Since it’s a “cycle”, you can start wherever you want.

Let’s start at the P wave of the EKG.

First, recall how the electricity travels through the ventricle.

Oh, that was easy, not nearly so complex as that damned P wave.

A wave—pressure increases from atrial contraction

X descent—in systole, as the ventricle contracts, the atrium is sort of “pulled down” and the pressure decreases

V ascent—venous blood flows into the atrium, increasing the pressure

Y descent—the tricuspid valve opens, pouring blood into the right ventricle and decreasing the pressure in the right atrium

Questions