Tube Carcinoma, Primary Fallopian

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

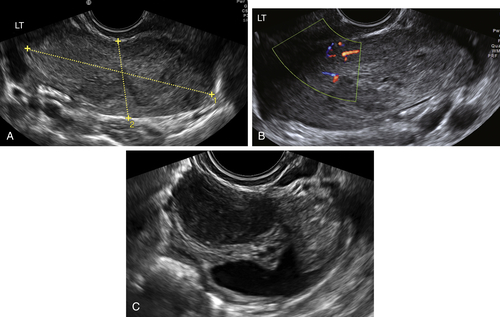

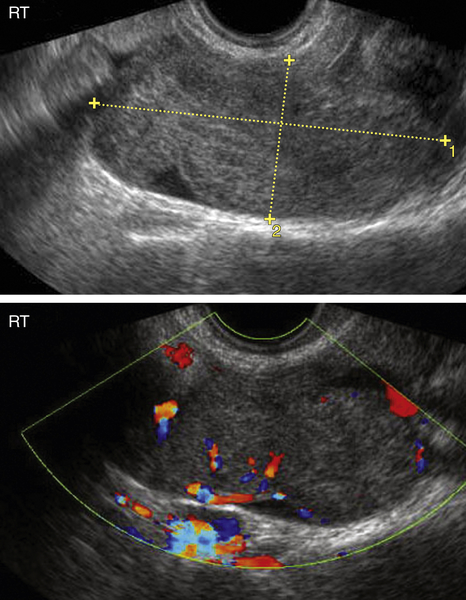

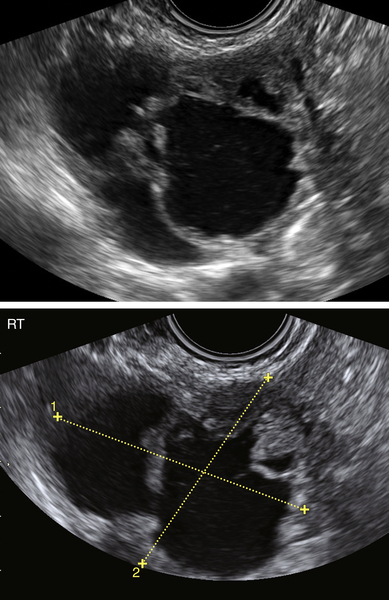

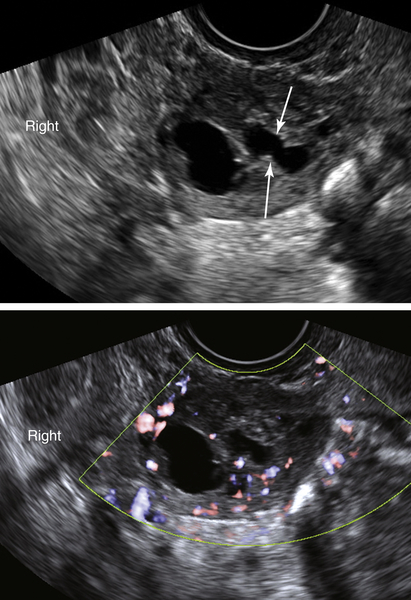

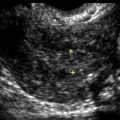

Ultrasound Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Figures

Suggested Reading

Chan A., Gilks B., Kwon J., Tinker A.V. New insights into the pathogenesis of ovarian carcinoma: time to rethink ovarian cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:935–940.

Haratz-Rubinstein N., Russell B., Gal D. Sonographic diagnosis of fallopian tube carcinoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:86–88.

Huang W.C., Yang S.H., Yang J.M. Ultrasonographic manifestations of fallopian tube carcinoma in the fimbriated end. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1157–1160.

Ko M.L., Jeng C.J., Chen S.C., Tzeng C.R. Sonographic appearance of fallopian tube carcinoma. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:372–374.

Seidman J.D., Zhao P., Yemelyanova A. “Primary peritoneal” high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:470–473.

Slanetz P.J., Whitman G.J., Halpern E.F., Hall D.A., McCarthy K.A., Simeone J.F. Imaging of fallopian tube tumors. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1321–1324.