Endometrial Carcinoma

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

Ultrasound Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Figures

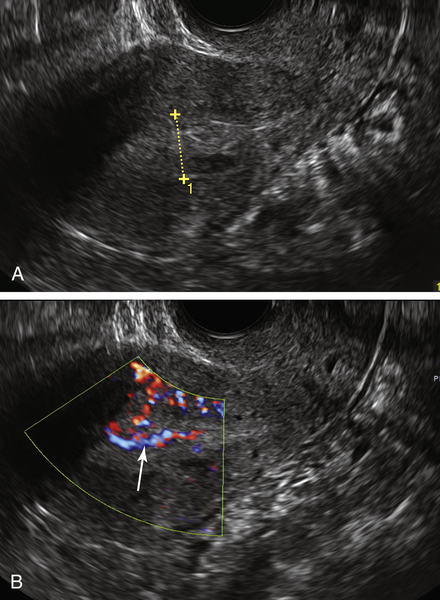

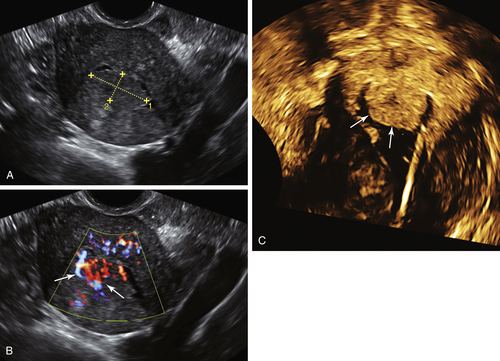

Figure E2-1 Polypoid endometrial cancer. A, A solid isoechoic mass in the endometrium (calipers). B, Extensive color flow displaying multiple, irregular vessels in the mass (arrows). C, A 3-D coronal rendering of the uterus after saline had been introduced into the cavity. Note the tumor (arrows) at the fundus of the uterus, outlined by fluid.

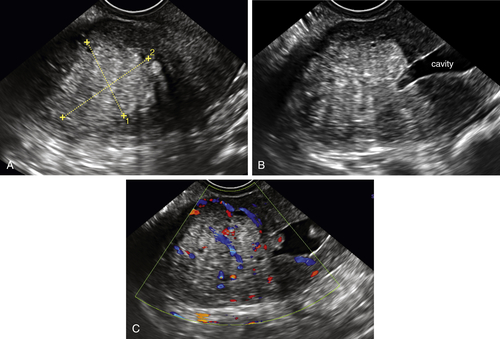

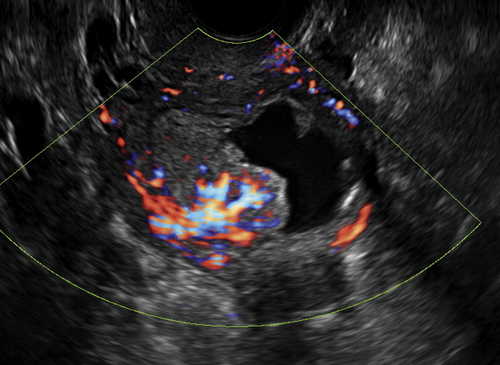

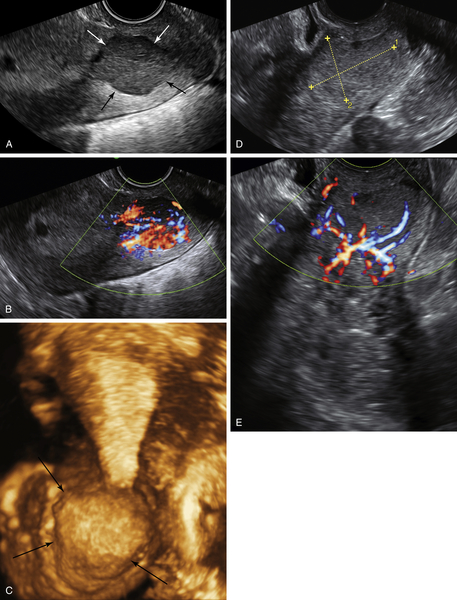

Figure E2-5 Two different patients with invasive endometrial cancer in the lower uterine segment and upper cervix. A and B, A solid, homogeneous mass (arrows) that is very vascular and located in the lower uterine segment and involving the upper portion of the cervix. C, The 3-D coronal view of the same mass showing its location in the lower portion of the uterus as well as its irregular contour (arrows). D and E, A different patient with a similar tumor (calipers) in the lower uterus/cervix. Note the disorganized abundant vascularity to the mass.

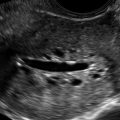

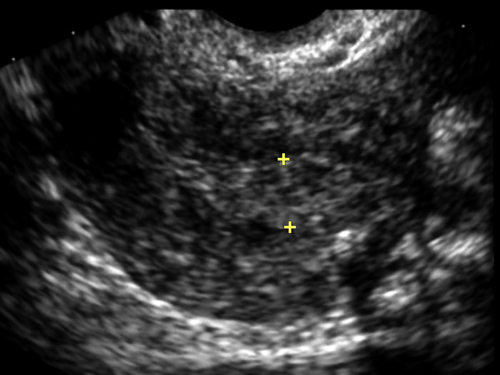

Figure E2-6 Endometrium of a 75-year-old asymptomatic woman who was on unopposed estrogen for more than 10 years. Despite the absence of bleeding, this endometrium of 8 mm was considered heterogeneous and abnormal, prompting sampling. Stage Ib endometrial carcinoma was diagnosed, invading one third of the way through the myometrium (invasion not detectable sonographically).

Videos

Suggested Reading

Amant F., Moerman P., Neven P., Timmerman D., Van Limbergen E., Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491–505.

Epstein E., Van Holsbeke C., Mascilini F., Måsbäck A., Kannisto P., Ameye L., Fischerova D., Zannoni G., Vellone V., Timmerman D., Testa A.C. Gray-scale and color Doppler ultrasound characteristics of endometrial cancer in relation to stage, grade and tumor size. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:586–593.

Leone F.P., Timmerman D., Bourne T., Valentin L., Epstein E., Goldstein S.R., Marret H., Parsons A.K., Gull B., Istre O., Sepulveda W., Ferrazzi E., Van den Bosch T. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of the endometrium and intrauterine lesions: a consensus opinion from the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis (IETA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:103–112.

Van den Bosch T., Coosemans A., Morina M., Timmerman D., Amant F. Screening for uterine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:257–266.