9 Cancers of the thorax

Lung cancer

Aetiology

Environmental and occupational hazards

Other risk factors

Pathogenesis and pathology

Malignant lesions

Box 9.1 shows a classification of lung tumours, which is based on light microscopic assessment of patterns of differentiation. The most important distinction is between small cell carcinoma (SCLC: 15–25% of lung cancers) and other carcinomas, collectively called non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC). These subgroups behave differently in their presentation, natural history and response to treatment.

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)

NSCLC consist of the following types:

Other neuroendocrine tumours

Presentation

Other symptoms

Paraneoplastic syndromes occur in up to 10% of patients. Box 9.2 lists the paraneoplastic syndromes. SCLC is the most common type associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Hypercalcaemia either due to excess parathyroid hormone (PTH) or PTH-related peptides is common in squamous cell carcinomas (15%). Hyponatremia occurs in up to 10% of patients, which is either due to syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH (SIADH) or to atrial natriuretic factor. SIADH is commonly associated with SCLC.

Signs

A normal physical examination does not exclude lung cancer.

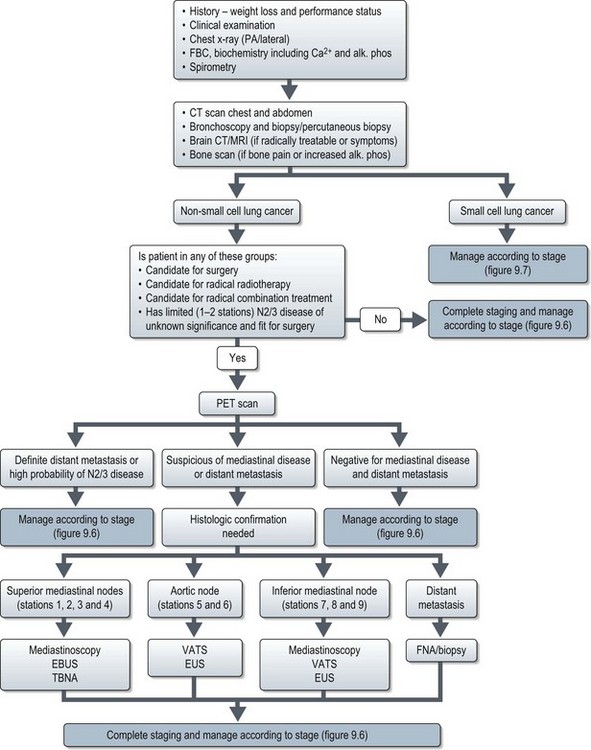

Investigations and staging (Figure 9.1)

Evaluation of a patient with suspected lung cancer is to:

Imaging

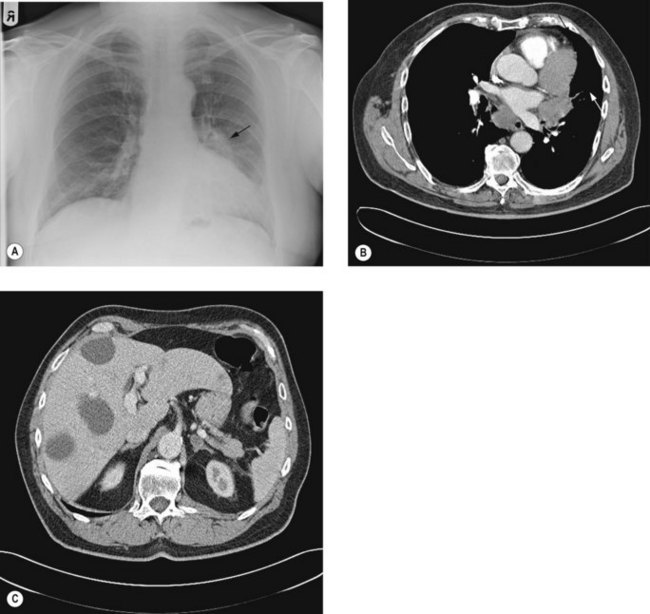

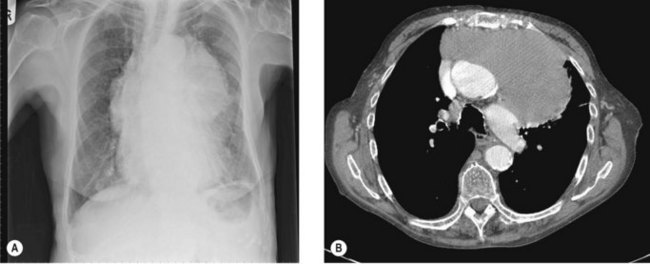

Chest X-ray (Figure 9.2A) may show lung lesion with or without lymphadenopathy. There can be associated lung collapse, pleural effusion, synchronous nodules or pericardial effusion. Bone metastases or bony destruction due to direct invasion can also been seen.

Contrast enhanced CT scan of chest, including upper abdomen (3–10% patients show asymptomatic liver and/or adrenal metastasis – Figure 9.2B&C) should be performed prior to further diagnostic investigations including bronchoscopy.

Bone scan is indicated if there is bone pain or isolated raised alkaline phosphatase.

Staging

Stage determines prognosis and guides treatment. TNM staging of lung cancer is given in Box 9.3. Small cell lung cancer can also be staged using a simple staging classification (Box 9.4). SCLC can be classified as TNM staging or using the simplied.

Box 9.3

Staging of non-small cell lung cancer

Stage Ib

| T2aN0M0 | Tumour >3 cm or ≤5 cm OR |

| Tumour of ≤5 cm with involvement of visceral pleura, main bronchus ≥2 cm distal to the carina or partial atelectasis |

Stage IIA

| T2bN0M0 | Tumour >5 cm or ≤7 cm |

| T1-T2aN1M0 | Metastasis in ipsilateral hilar or peribronchinal nodes |

Stage IIB

| T2bN1M0 | |

| T3N0M0 | Tumour of >7 cm OR |

| Tumour invading chestwall, diaphragm, phrenic nerves, mediastinal pleura or parietal pericardium OR | |

| Tumour <2 cm from carina, atelectasis of entire lung or nodule in the same lobe |

Stage IIIA

| T4N0-1M0 | Tumour invading mediastinal structures or nodule in different ipsilateral lobe |

| T1-3N2M0 | Metastases in ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal nodes |

Stage IIIB

| T4N2M0 | |

| anyT N3M0 | Metastases in contralateral hilar or mediastinal nodes |

| Metastases in scalene or supraclavicular nodes |

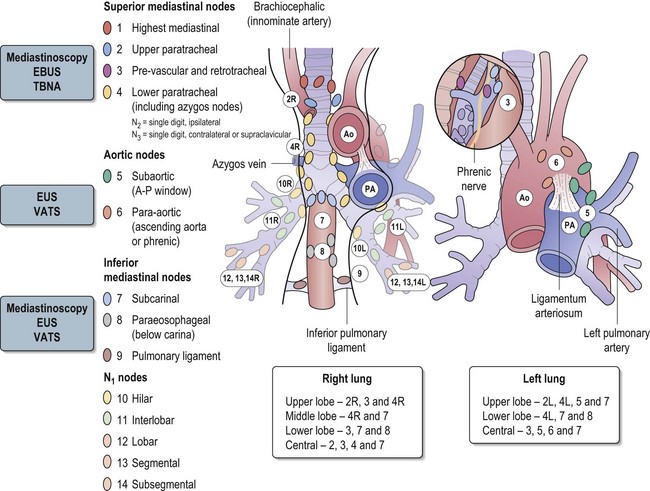

Mediastinal staging in non-small cell lung cancer

Accurate distinction of stages II, IIIA and IIIB is important in deciding optimal surgical treatment in the potentially operable patients. Stage II disease is treated with lobectomy or pneumonectomy with mediastinal sampling or dissection. Stage IIIA disease may be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed radical surgery or radical chemoradiotherapy, whereas IIIB disease is unresectable. This necessitates both an accurate distinction of T3 from T4 tumours and an accurate staging of nodal status. A classification of mediastinal nodes is shown in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 The classification of mediastinal nodes, patterns of nodal spread and method of choice of staging.

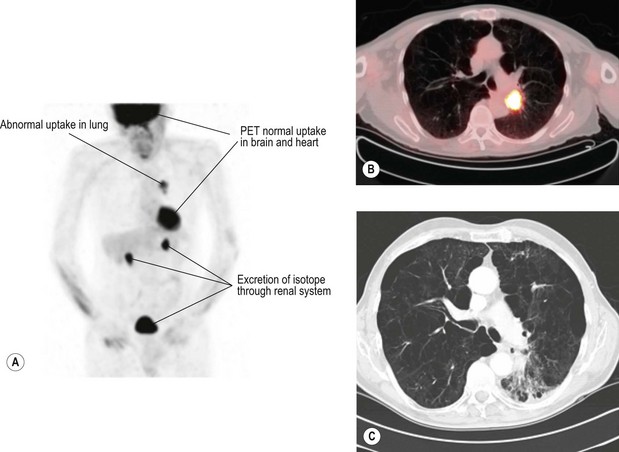

Methods of mediastinal staging

Positron emission tomogram (PET) (Figure 9.4) – PET is scan based on the principle of differential uptake of 2-[fluorine-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) by cancer cells. FDG is metabolized at a higher rate by tumour cells than normal cells and the areas of increased activity can be detected by a scanner. FDG-PET has higher sensitivity (87% vs. 68%), specificity (91% vs. 61%) and accuracy (82% vs. 63%) at detecting mediastinal disease than CT scan. PET also has a high negative predictive value in exclusion of N2/N3 disease, which helps to omit further mediastinal staging in case of a negative PET. Overall, there is 20% improvement in accuracy of PET over CT for mediastinal staging of NSCLC.

One of the limitations of PET is false-positive ‘hot spots’ in the mediastinum due to inflammatory processes (in up to 13 to 17%). It is less accurate when the lesion is <1 cm and in tumours of low metabolic activity such as carcinoid and bronchoalvelolar carcinoma.

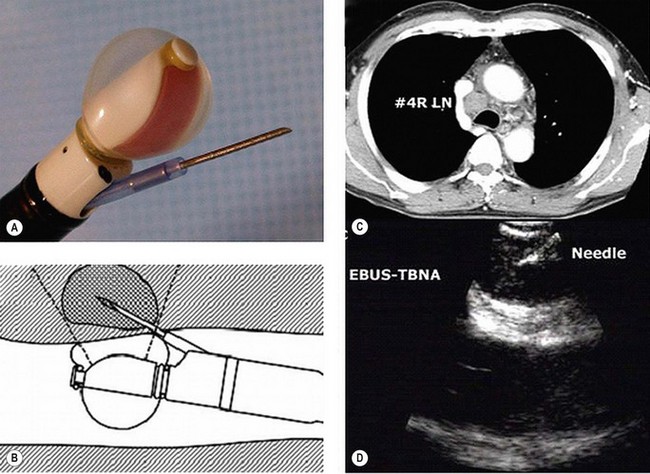

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) – EBUS is able to penetrate up to 5 cm and can identify lymph nodes and vessels. It is helpful in visualizing paratracheal (stations 2 & 4) and peribronchial lymph nodes (see Figure 9.3) and enables EBUS guided transbronchial needle aspiration (Figure 9.5). Sonographic features of malignant lymph node are round shape, sharp margins and hypoechoic texture. The advantage of EUS over CT and PET is that it can characterize lymph nodes smaller than 1 cm. It can also determine the depth and extent of tumour invasion of tracheobronchial lesions and helps to define the relationships to the pulmonary vessels and the hilar structures. EBUS has been found to predict the lymph node staging correctly in 96% of cases, with a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 100%.

Figure 9.5 Endobronchial ultrasound (A) and its use for FNA (B) of an enlarged lower paratracheal node (C&D).

Mediastinoscopy is generally regarded as the gold standard for preoperative mediastinal evaluation. CT scan is helpful in guiding selection of patients for mediastinoscopy prior to surgery. Cervical mediastinoscopy allows better access to contralateral lymph nodes. It is useful in evaluating paratracheal (2 & 4), scalene and inferior mediastinal nodes (7, 8 & 9). It is not useful in evaluating aortic nodes (5 & 6). Mortality rates from mediastinoscopy are negligible, but morbidity rates especially arrhythmias are reported to be 0.5–1%. It has to be borne in mind that up to 30% of patients with lung carcinoma who have a negative mediastinoscopy prove to have mediastinal nodal metastasis at surgery.

Management of lung cancer

Patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of lung cancer need urgent evaluation (Figure 9.1) and referral to a team specializing in the management of lung cancer. Treatment depends on type of lung cancer (NSCLC vs. SCLC), stage, performance status, co-morbidities and cardiopulmonary reserve.

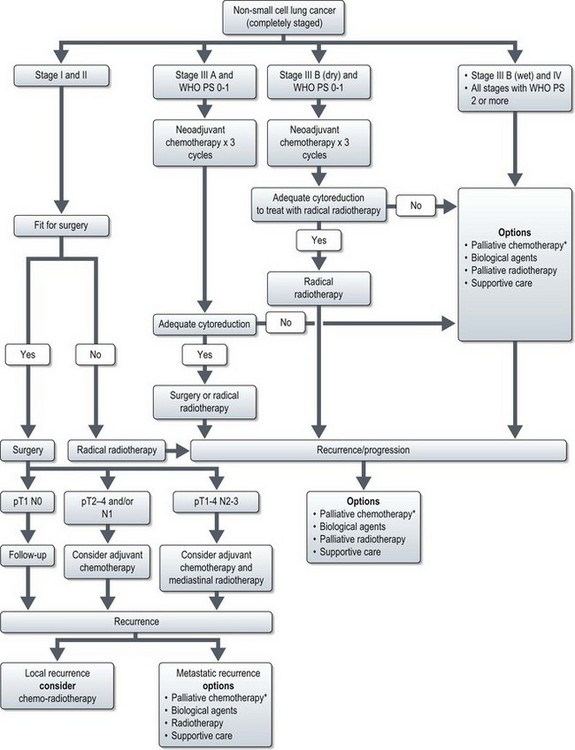

Non-small cell lung cancer (Figure 9.6)

Stage I–II

Figure 9.6 Management of non-small cell lung cancer. *palliative chemotherapy is considered only in patients with good performance status (0-2).

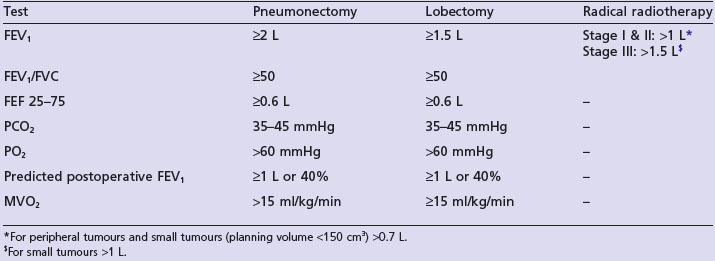

Radical surgery

Surgery offers the best prospect of cure in stage I–II disease, but only 10–20% of patients are suitable for surgery. Surgery is aimed at complete resection of the tumour and its intrapulmonary lymphatics. Patients need careful preoperative evaluation as they are often frail and frequently have cardiopulmonary morbidity due to chronic smoking. Spirometry is required in all patients. If the FEV1 is less than 1.5 L for lobectomy and less than 2 L for pneumonectomy, full lung function tests are required. Table 9.1 shows minimal pulmonary function required for different curative treatments. All patients require an ECG and patients with murmurs should have echocardiogram. Patients with known ischaemic heart disease should have detailed cardiologic assessment.

A complete anatomical resection is achieved by one of the following procedures:

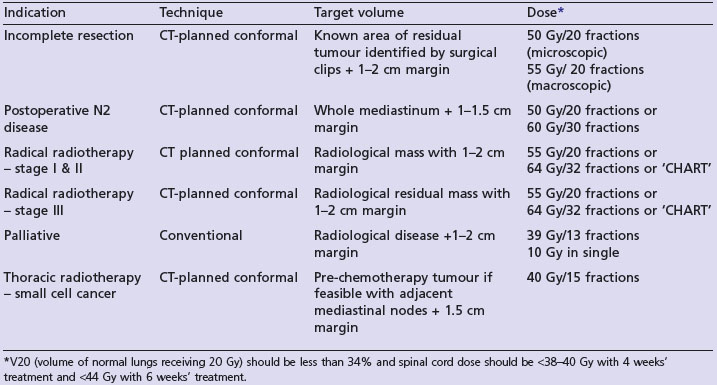

Radical radiotherapy (Table 9.2)

Patients with medically inoperable stage I/II are treated with radical radiotherapy if lung function is adequate (Table 9.1). In the only randomized trial, radiotherapy was inferior to surgery (4-year survival 7% vs. 23%). After conventional radical radiotherapy (60 Gy in 30 fractions over 6 weeks), 2-year survival is about 20%. A UK MRC study showed that 2-year survival is better (20 vs. 29%) with continuous hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART). This radiotherapy regime consists of 54 Gy in 36 fractions over 12 continuous days giving three fractions per day with a minimum interval of 6 hours between each fraction.

Postoperative treatment

Chemotherapy (Box 9.5)

In randomized trials, there is no survival benefit with adjuvant chemotherapy for stage IA. In stage IB and II, an early meta-analysis showed a 5% overall survival benefit with postoperative cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy. This has been supported by several recent trials of cisplatin combinations. The NCIC JBR 10 and ANITA trials both used vinorelbine and cisplatin. 5-year overall survival in NCIC JBR 10 trial was increased from 54 to 69% in stage IB and II disease. In the ANITA trial overall survival was not significantly different in stage IB (62% vs. 63%) but was statistically significant in stage II (52% vs. 39%) resected NSCLC. More heterogeneous trials which have allowed a wider range of tumour stages, more variety in chemotherapy combinations within the trial and less standardized surgical eligibility have provided less obvious benefits in survival (ALPI and European BIG lung trial). The IALT trial did however show a benefit in survival and the trial was closed early when the planned interim analysis showed a significant impact on survival with a median follow-up of 56 months. In summary, fit patients with resected stage IB–II should therefore be offered four courses of a cisplatin combination chemotherapy within 12 weeks of surgery.

Stage III

Stage IIIA (T1–3, N2 M0/T3 N1 M0)

New agents

Understanding some of the molecular mechanisms in NSCLC has led to the development of new targeted therapies. The mechanisms of these are common to several malignancies (see Appendis, p. 370). The most successful agents in NSCLC are those targeted against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Two oral drugs which inhibit the tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR are erlotinib (Tarceva™) and gefitinib (Iressa™). Toxicity with these drugs is unlike standard chemotherapy drugs and includes a characteristic rash which often reflects drug activity, diarrhoea and pneumonitis (reported in gefitinib in a Japanese study). The patients most likely to benefit from these drugs are female, those with an adenocarcinoma (especially bronchoalvelolar subtype), be non-smokers and be Asian. At the molecular level, increased EGFR protein expression, gene amplification and the presence of EGFR mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain increase patient response. A recent comparative study of gefitinib with a combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel (IPASS study) has shown that gefitinib results in a better progression free survival in patients with EGFR+ tumours.

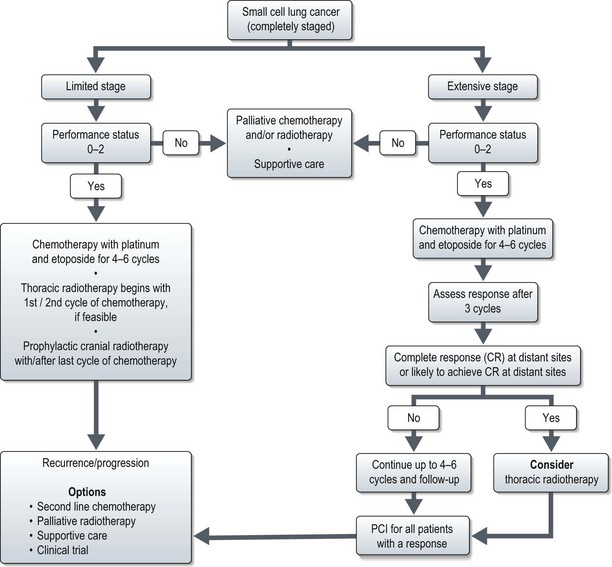

Small cell lung cancer (Figure 9.7)

Limited stage disease

In 5–10% of patients with SCLC limited to lung, diagnosis is established only after resection. These patients need adjuvant chemotherapy as there is high likelihood of development of distant metastasis. Role of surgery in early stage disease is not well established. Surgery following complete or partial response to chemotherapy is not beneficial.

Extensive stage

Chemotherapy is the main modality of treatment and a recent Cochrane review showed that in patients with extensive SCLC chemotherapy prolongs survival. One of the regimes shown in Box 9.5 is used.

Second-line chemotherapy

The median survival following relapse after first-line chemotherapy is approximately 4 months. There are two groups: the sensitive group who have previously responded and who have had a relapse-free-interval of at least 3 months and the resistant group who do not fit in the sensitive group. The sensitive group may be re-induced with same type of first-line chemotherapy. Of patients with sensitive disease 30–40% respond to second-line chemotherapy (median survival 6 months), while less than 10% of patients with resistant disease will respond to chemotherapy. The commonly used second line chemotherapy regimes are CAV or oral topotecan (Box 9.5).

Special situations

Superior sulcus tumour

Selected series of radical radiotherapy (60–66 Gy) alone report a 5-year survival of up to 40%.

Carcinoid tumours

Combination chemotherapy using the regimes as in SCLC is used to treat metastasis carcinoid.

Mixed small and non-small cell lung cancer

A small proportion of patients (2%) present with mixed small and non-small cell lung cancer. There is no clear recommendation for management of these tumours exists. Hence treatment should be individualized based on the stage of the disease and general condition of patients. Although, there is no role for surgery for pure small cell lung cancer; patients with localized mixed tumours may be candidates for aggressive surgery or chemo-radiotherapy (similar to NSCLC as it requires higher dose of radiotherapy for optimal long term control). Patients with poor performance status or metastatic disease are treated with palliative measures.

Lung cancer in never smokers

Never smokers are those who have smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Studies suggest that environmental tobacco smoke is a common cause of these cancers. Other risk factors may also contribute. Women are more commonly affected than men. Adenocarcinoma is more common, particularly the bronchoalveolar carcinoma subtype. Treatment is essentially the same as that of smokers. However, recent data suggest that this group of patients have a higher response rate and better survival with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as erlotinib and gefinib (see IPASS study, p. 102).

Palliative care issues

Mesothelioma

Pathogenesis and pathology

Investigations and staging

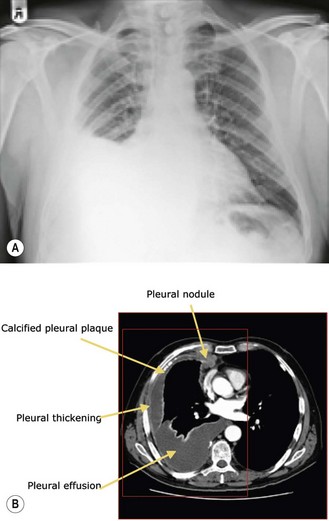

Imaging

Chest X-ray and CT scan (Figure 9.8) are the initial methods of imaging. Chest X-ray shows evidence of pleural thickening, pleural effusion and volume loss. CT scan shows unilateral pleural effusion, nodular pleural thickening and tumour encasement of the lung (‘rind like’ appearance – seen in 70% of cases) leading to contraction of hemithorax. Calcified plaques are found in 20% of patients. Chest wall invasion leads to obliteration of extrapleural fat planes, invasion of intercostal muscles, displacement of ribs, or bone destruction.

Staging

The recommended staging system is the International Mesothelioma Interest Group (IMIG) staging system, which is based on clinico-pathological tumour variables and nodal classification that of lung cancer (Table 9.3).

| Stage | |

|---|---|

| Ia | |

| T1aN0M0 | Limited to parietal pleura; no involvement of visceral pleura. |

| Ib | |

| T1bN0M0 | Limited to parietal pleura: scattered foci involving visceral pleura. |

| II | |

| T2N0M0 | Ipsilateral pleura with (i) involvement of diaphragmatic muscle or (ii) confluent visceral pleural tumor or extension from visceral pleura into the lung parenchyma. |

| III | |

| T3N0M0 | Ipsilateral pleura with involvement of the endothoracic fascia, or extension into mediastinal fat or solitary resectable extension of chest wall or non transmural involvement of pericardium. |

| T1–3N1M0 | Ipsilateral bronchopulmonary or hilar nodes. |

| T1–3N2M0 | Ipsilateral mediastinal or internal mammary nodes/subcarinal nodes. |

| IV | |

| T4N0M0 | Diffuse or multiple chest wall involvement; transdiaphragmatic extension to peritoneum; direct extension to contralateral pleura; mediastinal organ extension; extension to spine; extension to internal surface of pericardium or involvement of myocardium. |

| Any T, N3M0 | Contralateral mediastinal nodes; contralateral internal mammary nodes or any supraclavicular nodes. |

| Any T, Any N, M1 | Distant metastases present. |

Management

Radiotherapy

Prognostic factor and survival

There are two prognostic predictive models: EORTC and Cancer and Leukaemia group-B (CAL-B). EORTC system (Table 9.4) distinguishes patients with mesothelioma as good (median survival 10.8 months) and poor (5.5 months) prognostic groups, where as CAL-B distinguishes six groups with median survival ranging from 1.4 months to 13.9 months. Table 9.4 shows the EORTC prognostic index.

| Prognostic factor | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | +0.60 |

| Performance status | 1 or 2 | +0.60 |

| Histological diagnosis | Possible or probable | +0.52 |

| Sarcomatous type | Yes | +0.67 |

| WBC count | >8.5 × 109/L | +0.55 |

| Calculate total score by adding all the individual scores which can be 0–2.94 | ||

| Outcome measures | Good prognosis (total score ≤1.27) | Poor prognosis (total score >1.27) |

|---|---|---|

| Median survival | 10.8 months | 5.5 months |

| 1-year survival | 40% | 12% |

| 2-year survival | 14% | 0% |

New agents and future direction

Since the success of pemetrexed, there have been attempts to improve survival with targeted agents. Most mesotheliomas overexpress EGFR and there have been phase II trials with two EGFR small molecules, gefitinib and erlotinib. Gefitinib showed limited activity in less than 10% and erlotinib did not produce any responses. TKIs which act on the VEGF pathway have also been examined (p. 372). Both sorafneib and vatalanib have shown a small number of responses in pretreated patients. However, bevacizumab, the monoclonal antibody against VEGF, showed no improvement in survival or response when compared with chemotherapy alone in a randomized trial.

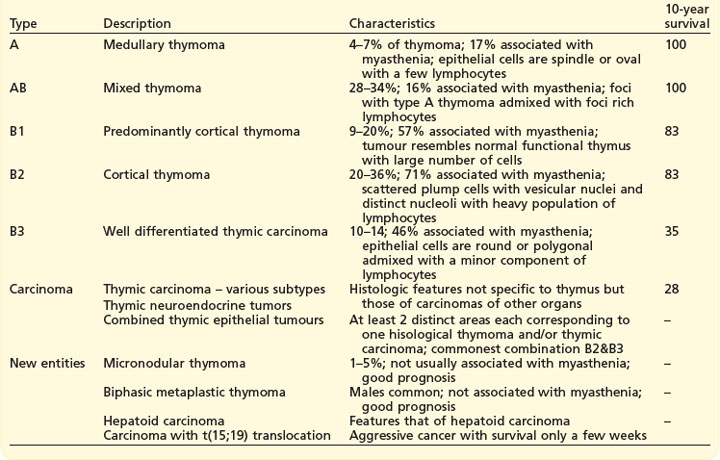

Thymoma

Pathology

WHO classification (Box 9.6) which correlates with prognosis, is based on the histological assessment of morphology of the neoplastic epithelial cells and the non-neoplastic lymphocytic component.

Investigations and staging

Imaging

In chest X-ray, large tumours are seen as mediastinal widening or anterior mediastinal mass (Figure 9.9A). The typical appearance in CT scan is a well-defined homogenous anterior mass lesion (Figure 9.9B) within a well-defined fibrous capsule. MRI scan is useful to evaluate mediastinal, cardiac and pericardial spread when CT findings are unequivocal.

Staging

Thymoma is staged according to Masaoka staging (Box 9.7), which is a postoperative staging. Invasion is the most important prognostic factor.

Box 9.7

Masaoka staging of thymoma

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Macroscopically completely encapsulated with no microscopic capsular extension |

| IIa | Microscopic invasion through the capsule |

| IIb | Macroscopic invasion into mediastinal fat or pleura |

| III | Invasion into adjacent structures (pericardium, lung or great vessels) |

| IVa | Pleural or pericardial metastases |

| IVb | Lymphatic or haematogenous metastases |

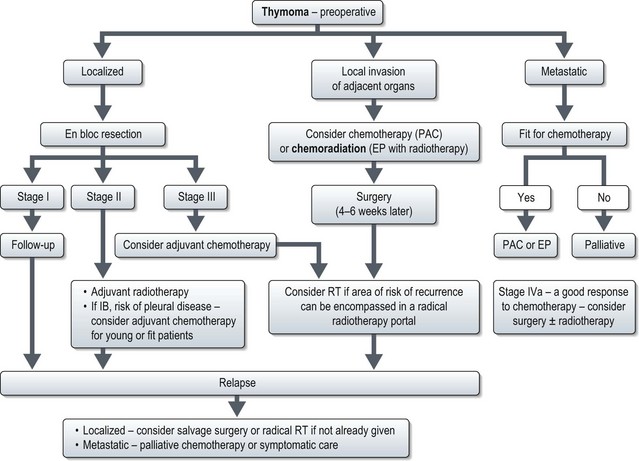

Management (Figure 9.10)

Successful treatment of thymoma depends on complete surgical resection. The majority of thymomas confined to the thymus are amenable to curative resection. Stage-wise management of thymoma is shown in Figure 9.10.

Locally advanced disease (stage III and IVA)

If stage III or IVA with limited pleural disease is suspected preoperatively, patients should be treated with neoadjuvant treatment. This can be either chemotherapy alone (PAC) or chemoradiotherapy (EP with 45 Gy of radiation) (see below). Surgery is done 4–6 weeks after neoadjuvant treatment. Patients who haven’t had radiotherapy preoperatively, should be considered for postoperative radiotherapy (Box 9.8) provided the area of risk can be encompassed in a radical radiotherapy portal and pulmonary function tests are adequate.

Metastatic disease

Chemotherapy

Patients who fail surgery and/or radiotherapy or who present with metastastic disease are candidates for chemotherapy (Box 9.9). However, there are no randomized trials of chemotherapy in thymoma. Studies showed that a combination of cisplatin, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (CAP) resulted in an overall response of 50%, medial duration of response of 12 months and median survival of 38 months. Another combination regime of etoposide and cisplatin (EP) showed a response rate of 56% with median response of duration of 3.4 years and median survival of 4.3 years. Hence CAP and EP remains the standard chemotherapy combination for thymomas and thymic carcinoma.

1 Commonly seen in small cell lung cancer,

4 large cell carcinoma,

5 adenocarcinoma.

Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1367-1380.

Bonomi PD. Implications of key trials in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:1155-1164.

Puglisi M, Dolly S, Faria A, et al. Treatment options for small cell lung cancer – do we have more choice? Br J Cancer. 2010;102:629-638.

Tassinari D, Drudi F, Lazzari-Agli L, et al. Second-line treatments of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: new evidence for clinical practice. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:428-429.

Dempke WC, Suto T, Reck M. Targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;67:257-274.

Stahel RA, Weder W. Improving the outcome in malignant pleural mesothelioma: nonaggressive or aggressive approach? Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21:124-130.

Ceresoli GL, Zucali PA, Gianoncelli L, et al. Second-line treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:24-32.

Falkson CB, Bezjak A, Darling G, et al. The management of thymoma: a systematic review and practice guideline. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:911-919.