14 Cancers of the skin

Cutaneous melanoma

Aetiology

Pathology

There are four histological variants of cutaneous melanoma:

Other forms of melanoma include ocular, mucosal and vulval (p. 236).

The histology of melanomas is very variable depending on the specific subtype and primary site. Many of the features assessed by histology have prognostic value (Box 14.1). In addition to these the pathologist should report the type of melanoma, greatest thickness, radial or vertical growth phase, excision margins and immunohistochemical stains. Immunohistochemical stains used in melanoma include S100 (the most frequently used but also stains benign melanocytes), HMB-45, Mitf, MART-1 and tyrosinase.

Initial assessment

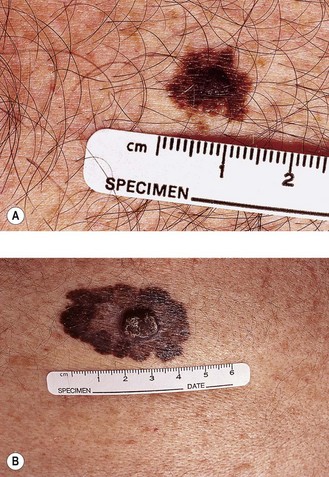

Initial assessment of patients with suspected melanoma includes detailed examination and a clinical photograph of the lesion, full skin examination and examination for lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly. Clinical signs of melanoma include itching, bleeding, ulceration or changes in a pre-existing mole. ABCDE features (Figure 14.1) help to distinguish early melanoma from a benign mole:

Investigations

In the absence of clinical evidence of metastatic disease in regional lymph nodes at presentation, there is no indication for any staging investigations. In patients with thick primary tumours (>4 mm), CT scan may be useful prior to rule out metastatic disease. Studies show that a routine chest X-ray revealed metastasis in only 0.1% whereas 15% showed false positivity. Similarly CT scan showed metastasis in 1.3% while false positivity was 16%.

Staging

Breslow thickness, ulceration and mitotic count are most important prognostic factors of localized disease whereas Clark level is an independent prognostic factor for melanoma of <1 mm thickness (Box 14.1). Staging is by TNM AJCC system and is related to prognosis (Table 14.1). M1a includes distant skin, subcutaneous or nodal metastases with a normal LDH. M1b is lung metastases with a normal LDH and M1c is with any other metastases or with a raised LDH level.

Table 14.1 TNM staging & 5-year survival of cutaneous melanoma

| Staging | 5-year survival (%) |

|---|---|

| Stage IA | 95 |

| T1aN0M0 ≤1 mm thickness without ulceration and mitosis <1/mm2 | |

| Stage IB | 91 |

| T1bN0M0 ≤1 mm thickness with ulceration or mitosis ≥1/mm2 | |

| T2aN0M0 1.01–2 mm thickness without ulceration | |

| Stage IIA | 77–79 |

| T2bN0M0 1.01–2 mm thickness with ulceration | |

| T3aN0M0 2.01–4 mm thickness without ulceration | |

| Stage IIB | 63–67 |

| T3bN0M0 2.01–4 mm thickness with ulceration | |

| T4aN0M0 >4 mm thickness without ulceration | |

| Stage IIC | 45 |

| T4bN0M0 >4 mm thickness with ulceration | |

| Stage IIIA | |

| T1-4aN1aM0 Micrometastasis* in 1 node | 70 |

| T1-4aN2aM0 Micrometastasis in 2–3 nodes | 63 |

| Stage IIIB | |

| T1-4bN1a/2aM0 | 50–53 |

| T1-4aN1bM0 Macrometastasis** in 1 node | 46–59 |

| T1-4aN2bM0 Macrometastasis in 2–3 nodes | 46–59 |

| T1-4aN2cM0 in-transit metastases/satellites without nodes | |

| Stage IIIC | 24–29 |

| T1-4bN1b/2b/2cM0 | |

| Any T N3M0 metastasis in >3 nodes or matted nodes or in-transit or satellites with metastatic nodes | |

| Stage IV | |

| Any T, any N, M1 distant metastasis | 7–19% |

*micrometastases after sentinel node biopsy; **macrometastases are clinically detectable pathologically confirmed nodes.

Management

Non-metastatic disease

Adjuvant treatment

No trial has shown a survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy in localized malignant melanoma. Due to the activity of immune treatment in advanced melanoma several trials have examined the role of interferon and vaccines in the adjuvant treatment of melanoma. A pooled analysis of three ECOG studies showed that adjuvant high dose interferon improves relapse-free – survival (about 10% at 5- years) but not overall survival in patients with a high-risk resected melanoma. This group included patients with ≥4 mm thick with no nodal involvement and melanoma involving regional nodes or in-transit metastasis. However, high dose interferon is associated with a number of side effects such as acute constitutional symptoms, chronic fatigue, headache, weight loss, nausea, myelosuppression and depression and most patients will require dose modifications during treatment.

Management of positive nodes

Patients with metastatic lymph node disease are treated with regional node dissection if feasible and up to 13–59% of these patients do not develop metastatic disease. There is a significant risk of lymphoedema (especially with groin dissections) and patients should wear compression stockings for many months. Some trials are examining the role of adjuvant treatment, such as bevacizumab, after groin dissection. A randomized study has evaluated the role of postoperative radiotherapy (48 Gy in 20 fractions) in patients with a high risk (>25%) of regional recurrence after lymphadenectomy. The two-year lymph node field relapse-free rate was significantly improved with adjuvant radiotherapy compared with observation (82 vs. 65% HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.28–0.67); but without no improvement in 2-year overall survival. The long term toxicity of radiotherapy yet to be reported.

Management of metastatic disease

Role of radiotherapy

Palliative radiotherapy is useful in bone metastasis and spinal cord compression not amenable to surgical decompression (p. 328). Skin metastases which are rapidly enlarging and about to ulcerate can also be treated with palliative radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy and other systemic treatments in metastatic disease

Dacarbazine is the standard intravenous chemotherapy drug for metastatic melanoma with a response rate of 10–20% and a median duration of response of 3–6 months. It is given 3–4 weekly at doses of 850–1000 mg/m2 with nausea as the main side effect. Temozolamide is an oral analogue of dacarbazine and crosses the blood–brain barrier but is more expensive and has no improvement in response rates compared with dacarbazine (Table 14.2). There is no evidence that combination chemotherapy regime is superior to single agent drugs in terms of response rates or survival.

Table 14.2 Response rates (%) for single agents in metastatic melanoma

| Agent | % Response rate (CR + PR) |

|---|---|

| Dacarbazine | 20 |

| Temozolamide | 21 |

| Carmustine (BCNU) | 18 |

| Lomustine (CCNU) | 13 |

| Cisplatin | 23 |

| Carboplatin | 16 |

| Vinblastine | 13 |

| Paclitaxel | 18 |

| Docetaxel | 15 |

A recent study of ipilimumab, a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), showed improved overall survival in previously treated patients with unresectable stage III/IV melanoma who were positive for HLA-A*0201. Side effects of this treatment included rash, colitis, diarrhoea and hepatitis.

Prognostic factors and survival

Prognostic factors are highlighted in Box 14.1. Survival according to stage is included in Table 14.1.

Non-cutaneous melanoma

Ocular melanoma

Poor prognostic factors include age over 60, size and involvement of the ciliary body. Although often localized at presentation they have a high risk (10–80% depending on number of prognostic factors) to spread to the liver, often several years after successful treatment of the primary. Long-term survival is less than 35% even with successful treatment of the primary. Surgery used to be the standard treatment but radiotherapy has replaced this in most cases. Radiotherapy can be administered as external beam, as a radio-active plaque (e.g. iridium-192) or with protons or other charged particles. Local control rates are similar with each technique. The vision is often lost in the irradiated eye with the list of complications including cataracts, glaucoma, retinopathy and vitreous haemorrhage.

Basal cell carcinoma

Clinical features

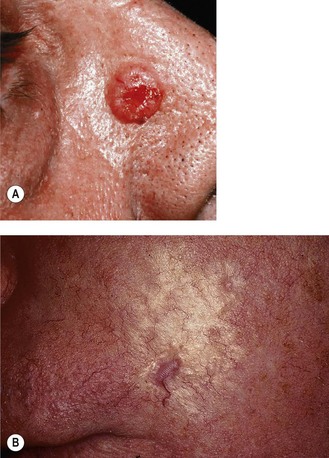

The common growth patterns are superficial, multifocal, nodular and morphoeic (Figure 14.2). The sites affected are head and neck (52%), trunk (27%), upper limb (13%) and lower limb (8%).

Other histolological subtypes are uncommon and do not have any characteristic clinical presentation.

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at eradication of tumour with acceptable cosmetic and functional outcome. A number of treatment options are available (Box 14.2) and the choice of treatment in small BCC depends on various factors (Box 14.3). Radiotherapy is indicated when cosmetic and/or functional outcome is better with radiotherapy compared with surgery and when there is a need to avoid complex plastic surgery.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy results in 93–95% 10-year control rate for BCC of ≤2 cm. Radiotherapy details are given in Box 14.4.

Box 14.4

Radiotherapy for skin cancer

Type of radiation

Depends on depth of penetration needed and type of underlying tissue.

Radiotherapy dose

| BCC | SCC |

|---|---|

| 60 Gy/30 fractions/6 weeks* | 60–66 Gy/30–32 fractions |

| 50 Gy/20 fractions/4 weeks* | 55 Gy/20 fractions |

| 40 Gy/15 fractions/3 weeks | 40 Gy/10 fractions |

| 40.5 Gy/9 fractions/3 weeks | 45 Gy/9 fractions |

| 32.5 Gy/5 fractions/1 week | 32.5 Gy/5 fractions |

| 32 Gy/4 fractions/4 weeks** | 32 Gy/4 fractions/4weeks |

| 12–15 Gy/1 fraction** | 12–15 Gy/1 fraction |

Special considerations

Electron planning

Squamous cell carcinoma

Pathology

In situ (Bowen’s disease) SCC is limited to epidermis which presents as a flat scaling pink lesion with irregular borders. There is no risk of metastasis, although progression to invasive SCC occurs in 3–11% of cases.

Clinical presentation

Typical presentation is a raised pink papule or plaque with erosion or ulceration (Figure 14.3). In advanced cases it presents as large ulcerated masses and bleeding. Metastasis is primarily to the regional nodes (2–6%). The head and neck region is the commonest site in men whereas the upper limb followed by head and neck are the commonest sites in females. Only 8% of SCC arise on the trunk.

Treatment

Surgery

Surgery is aimed at complete removal of the tumour and of any metastasis. Low-risk tumours of <2 cm are excised with a minimal margin of 4 mm whereas tumours of >2 cm size, high risk tumours (grade 2–4, in high risk locations such as ear, lip, scalp, eyelids and nose) and those extending into subcutaneous tissue need a minimum margin of 6 mm or more. Depth of excision should be through normal underlying fat. The accepted minimal microscopic margin is >1 mm.

Mohs’ micrographic surgery is indicated in high risk tumours and recurrences.

Radiotherapy

Principles of primary radiotherapy and treatment guidelines are same as that of BCC (Boxes 14.3 and 14.4). 5-year control rate with radiotherapy is comparable with surgery with >93% for T1 lesions, 65–85% with T2 and 50–60% with T3–4 lesions. Radiotherapy is indicated after incomplete excision when further surgery is not contemplated, as incomplete excision leads to 50% local recurrence.

Prognostic factors

Merkel cell carcinoma

Clinical features

MCC present as red or violaceous nodules with a shiny surface, often with overlying telangiectasia (Figure 14.4). Spread through dermal lymphatics can result in the development of satellite lesions. The most common site of disease is the head and neck region, followed by extremities and trunk. One-third of patients have regional nodal metastases at presentation and 50% develop distant metastasis. Liver, lung, bone and brain are the sites of distant metastases.

Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:270-283.

Mouawad R, Sebert M, Michels J, et al. Treatment for metastatic malignant melanoma: old drugs and new strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:27-39.

Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Kefford RF. Cutaneous melanoma in the era of molecular profiling. Lancet. 2009;374:362-365.

Miller AJ, Mihm MCJr. Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:51-65.

Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton CA. Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:35-48.

Veness MJ. The important role of radiotherapy in patients with non-melanoma skin cancer and other cutaneous entities. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:278-286.

Neville JA, Welch E, Leffell DJ. Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer in 2007. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:462-469.

Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.

Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

Willemze R, Dreyling M. Primary cutaneous lymphoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):115-118.