21 Cancers of the haematopoietic system

Hodgkin’s disease

Aetiology

Pathology

The WHO classification of HD is shown in Table 21.1. Nodular sclerosis is the common subtype in young adults (more common in females), which presents with early stage supradiaphragmatic disease whereas mixed cellularity presents with generalized lymphadenopathy or extranodal disease with B symptoms. Lymphocyte depletion type presents with advanced stage disease with extranodal involvement and aggressive clinical course.

| Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s lymphoma (grades 1 and 2) | 60–70% |

| Mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 20–30% |

| Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (LRCHL) | 3–5% |

| Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin’s lymphoma (LDHL) | 0.8–1% |

| Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (LPHL) | 3–5% |

LRCHL usually presents in young males with localized cervical node involvement with no B symptoms.

Investigations and staging

Imaging

Staging

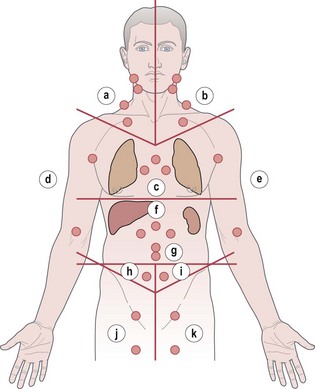

Cotswolds modification of the Ann Arbor Classification is used for staging (Table 21.2).

Table 21.2 The Cotswolds modification of Ann Arbor staging for lymphoma

| Stage I | Involvement of a single lymph node region or lymphoid structure or involvement of a single extralymphatic site (IE) |

| Stage II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm; localized contiguous involvement of only one extranodal organ or site and lymph node region(s) on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE) |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III),which may also be accompanied by involvement of the spleen (IIIS) or by localized contiguous involvement of only one extranodal organ site (IIIE) or both (IIISE) |

| Stage IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extranodal organs or tissues, with or without associated lymph node involvement |

| Designations applicable to any disease stage | |

| A: | No B symptoms |

| B: | Presence of B symptoms |

| X: | Bulky disease (a widening of the mediastinum by more than one third of the chest or presence of a nodal mass with a maximal dimension greater than 10 cm) |

Management

Patients with early stage disease (clinical stage I/II) are categorized as favourable and unfavourable group based on risk factors (Table 21.3). Prognosis of patients with advanced-stage (stage III and IV) disease is defined using the International Prognostic Score (IPS) (Box 21.1).

| Treatment group | Definition |

|---|---|

| Favourable | CS I–II without risk factors |

| Unfavourable | CS I–II with ≥ 1 risk factors |

| Risk factors |

* Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (≥50 mm/h without or ≥30 mm/h with B-symptoms).

Classical HD

Early-stage favourable

The current standard treatment is combined modality treatment, consisting of two to four cycles of ABVD chemotherapy (Boxes 21.2 and 21.3), followed by 30–35 Gy in 15–20 fractions of involved field radiotherapy (IF-RT).

Box 21.2

Radiotherapy techniques in lymphoma

Early-stage unfavourable

These patients are also treated with combined modality treatment; however, the optimal chemotherapy regime and radiotherapy fractionation are yet be determined. The current treatment is four courses of ABVD followed by involved field radiotherapy of 30–35 Gy in 15–20 fractions (Boxes 21.2 and 21.3). With this treatment 5% patients progress during or immediately after treatment and 15% relapse within 5 years.

Follow-up

Two-thirds of relapses occur within 3 years of initial treatment and more than 90% occur within 5 years. Since a significant proportion of patients who relapse can be successfully salvaged, all patients need regular follow-up (Box 21.4). Follow-up is also helpful in identifying and managing long term side effects such as endocrine dysfunction.

Box 21.4

Follow-up and screening after treatment for HD

Survivorship issues

The major causes of excess death in survivors of HD are second malignancies and ischaemic heart disease (p. 58).

One of the most common second malignancies is lung cancer which is attributed to mediastinal radiotherapy, chemotherapy and smoking. Patients who had thoracic radiotherapy are encouraged not to smoke. There is 20–50% risk of second breast cancer after mediastinal/axillary radiotherapy in young females and these patients should be screened for breast cancer. Common haematological neoplasms include acute myeloid leukaemia, myelodysplastic syndrome (develops within 3–5 years) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (develops after 5–15 years).

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Pathology

The cell of origin is different for each subtype of lymphoma. Classification is by the updated WHO modification of the REAL (revised European and American lymphoma) classification system which is broadly divided into B-cell, T-cell/natural killer cell and Hodgkin’s disease (Table 21.4). Table 21.5 shows cytogenetic and molecular characteristics of NHL.

| B-cell neoplasms |

Table 21.5 Cytogenetic and molecular characteristics of NHL

| Lymphoma | Cytogenetics | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Burkitt’s | ||

| Follicular lymphoma | t(14:18)(q32;q21) | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | t(14:18)(q32;q21)+others such as p53, p16, p15 | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | BCL-1 or PRAD1 (11q) Ig heavy chain (14q) |

| Anaplastic lymphoma | t(2;5)(p23:q35) |

Evaluation and staging

Imaging

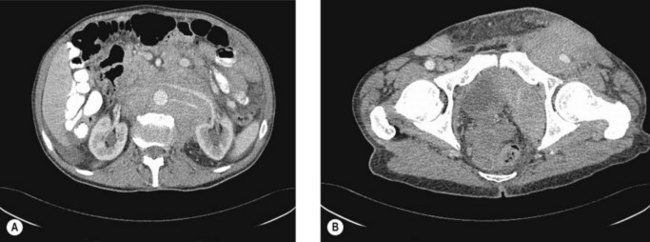

CT scans of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis are carried out to assess lymphadenopathy and organ involvement (Figure 21.3).

Prognostic factors

Stage, age, LDH and performance status have prognostic value. The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIP) score is used for indolent lymphomas (Box 21.5). The international prognostic index (IPI) is used for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Box 21.6).

Treatment

Follicular lymphoma

Early stage

Only about one-third of patients with follicular lymphoma present with stages I and II or limited stage III (with up to five involved lymph nodes areas) disease. Treatment options include watchful waiting, or radiotherapy (Box 21.2).

Advanced stage

The commonly used regime is either single agent chlorambucil or fludarabine. Chlorambucil results in 50–75% response rate with no complete response, whereas fludarabine can result in a complete response (15%). Combination chemotherapy (e.g. CVP and CHOP) (Table 21.6) have no overall survival benefit. The role of chemotherapy with rituximab is being investigated. Elderly patients may be treated with rituximab or single agent chemotherapy.

High-grade lymphoma

High-grade lymphomas include a number of lymphoma subtypes including:

DLBCL

In early-stage disease without adverse factors (see Box 21.6), treatment is with 3–4 cycles of CHOP in combination with rituximab (R-CHOP) followed by involved-field radiation therapy (30–35 Gy in 1.75–3 Gy per fraction) or 6–8 cycles of R-CHOP.

Burkitt’s lymphoma

Burkitt’s lymphoma is a rare (2–3%) aggressive B cell NHL There are two main forms: the endemic form observed in Africa and associated with EBV and the sporadic form which accounts for up to 30% childhood lymphomas (p. 323, children’s cancers). The endemic form classically presents with enlargement of the jaw. The sporadic form presents rapidly increasing disease with intra-abdominal masses often involving the gastrointestinal tract (especially ileocaecal), ovaries or kidneys. Bone marrow and CNS involvement is frequent. These patients are at a high risk of developing tumour lysis syndrome due to an almost 100% cell turnover (p. 342). Survival rates vary from 30% to 70% and have improved with intensive regimes and risk group. Low-risk patients include those with a low LDH and those with a completely resected abdominal/single lesion. All others should be considered high risk.

Mantle cell lymphoma

Optimal initial treatment in MCL is yet to be established. The commonly used first line chemotherapy regime is CHOP. Other first line options include fludarabine-containing regimens, single agent cladribine and a combination of high-dose methotrexate with cytarabine. Consolidating autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission improves progression free survival in eligible younger patients. Rituximab maintenance therapy seems to be a therapeutic alternative particularly in elderly patients. In relapsed patients, fludarabin-containing regimens, bendamustine and bortezomib seem to be effective. In the absence of allogenic stem cell transplantation, a potentially curative but investigative treatment option, the median survival is 4–6 years.

Primary extra-nodal NHL

Primary CNS lymphoma

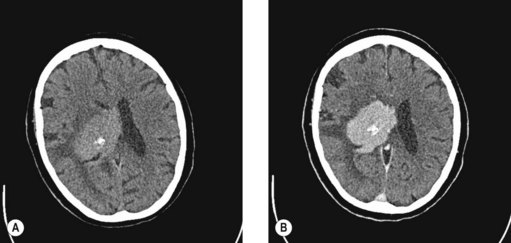

Primary CNS lymphoma occurs are a median age of 60 years in immunocompetent patients and 30 years in HIV patients. Primary CNS lymphoma often has a rapidly progressive course. Systemic dissemination is rare. The finding of characteristic features on CT (Figure 21.4) and MRI imaging should prompt a stereotactic biopsy. Management of primary CNS lymphoma is discussed on p. 276.

Testicular lymphoma

Primary testicular lymphoma represents 1–2% of all NHL. It is the most common malignancy of the testis in men older than 60 years and the most common presentation is unilateral painless scrotal swelling. DLBCL is the most common histology and diagnosis is usually established by initial orchidectomy. Approximately 80% of cases are stage I or II at presentation. A low IPI, no B-symptoms, the use of anthracyclines, and prophylactic contralateral scrotal radiotherapy are significantly associated with longer survival. Systemic chemotherapy alone seems not to be effective in preventing relapses in the contralateral testis because the testis is a sanctuary site (p. 35). Treatment consists of 6–8 courses of R-CHOP followed by prophylactic irradiation of the contralateral testis. Although data are not convincing, prophylactic intrathecal therapy should be considered. This approach results in a 3-year overall survival of 86% and 3-year progression-free survival 77%.

Cutaneous NHL

Clinical features

Mycosis fungoides typically presents with erythematous patches, plaques and tumours usually in areas not often exposed to sunlight (Figure 21.5). Most patients have multiple lesions and ulcerations can occur. The course of the disease is indolent.

Management of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

Patients with more advanced disease will require systemic treatment. Total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT) is appropriate in patients with generalized thickened plaques due to its depth of penetration. The rate of complete responses is greater than 80% but the long-term outcome is not affected. TSEBT should be followed by an adjuvant therapy such as mechlorethamine or PUVA.

Acute leukaemias

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) occurs most frequently either between the ages of 15–25 (p. 321) or over the age of 75. In the UK there are 200 new adult cases per year and the male : female ratio is roughly equal. Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) occurs more frequently and the median age at presentation is 65. In the UK, around 2000 new cases are diagnosed per annum.

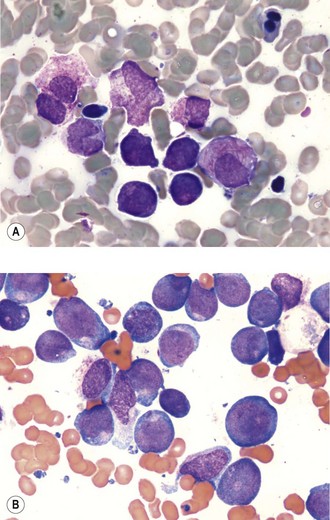

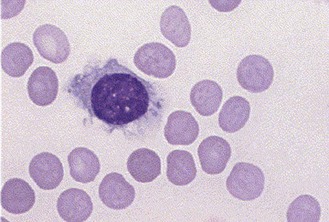

Pathology

AML and ALL are characterized by circulating blasts cells which may be seen in the peripheral blood. Bone marrow examination with immunophenotypic analysis is needed for establishing a diagnosis. Both myeloblasts and lymphoblasts are characterized by a high nuclear : cytoplasmic ratio and prominent nuclei. Azurophilic Auer rods are pathognomonic of AML (Figure 21.6).

Prognostic factors and risk classification

AML

Based on cytogenetics there are three prognostic groups in AML:

ALL

Current treatment of adult ALL leads to long-term survival of 30–40%. Initial chemotherapy utilizes vincristine, corticosteroids and daunorubicin (induction). Such intensive combination chemotherapy results in a complete remission (CR defined as <5% blast cells with return of marrow cellularity and function and disappearance of extramedullary manifestations) in 80–90% cases. Once CR is achieved consolidation therapy is started with a combination of chemotherapy. In patients with Ph+ disease, concurrent tyrosine inhibitor imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor [p. 312]) may improve survival. CNS directed treatment with intrathecal methotrexate and high-dose methotrexate and/or cranial radiation to treat the central nervous system is required for patients who are not planned to have undergo bone marrow transplantation.

Salvage therapy

The outcome of salvage therapy remains unsatisfactory. CR rates range from 10–50% and long-term DFS is poor. Various combinations of chemotherapy are used. Although stem cell transplantation (SCT) is superior to chemotherapy with long-term DFS rates of 20–40% in salvage therapy, only 30–40% of patients who achieved a second complete remission are eligible for SCT and fewer than 50% have enough time before disease recurrence to undergo SCT.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia

Natural history

The three phases of disease are:

Investigations

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

Clinical features

10% patients can undergo transformation to a more aggressive tumour, most commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, called Richter’s syndrome.

Diagnosis

Staging

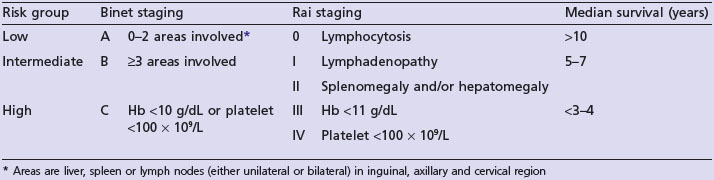

Two staging systems exist based on the extent of disease and bone marrow failure and correlate with median survival (Table 21.7).

Treatment

Supportive treatment

Patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia with recurrent infection need regular intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg 3–4 weekly). Patients on intensive treatment with purine analogues and alemtuxumab (Campath) need Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis. All patients need influenza vaccine annually.

Hairy cell leukaemia

Peripheral smear shows cytopenia and the presence of hairy cells, cells twice the size of a normal lymphocyte with cytoplasmic projections and an oval nucleus (Figure 21.7). Bone marrow biopsy is important in definitive diagnosis, which shows an interstitial or focal pattern of infiltration. Immunophenotyping is necessary to distinguish HCL from other B-cell lymphomas.

Myelodysplastic syndromes

There are a number of types including:

In the majority of cases, MDS occurs as a de novo disorder; recently secondary MDS/AML as a result of chemotherapy/radiotherapy is increasing. Radiotherapy and alkylating agent related MDS occurs 5–6 years after treatment whereas topoisomerase II inhibitor (e.g. etoposide and teniposide) related MDS develops at a median interval of 33–34 months after exposure.

Solitary plasmacytoma

Diagnosis

The diagnostic approach is the same as that for myeloma and solitary plasmacytoma is diagnosed when there is no evidence of myeloma. MRI of the spine and pelvis should be performed in all patients as up to one-third of patients may have additional occult lesions that will be missed on skeletal survey (Figure 21.8). There may be a monoclonal gammopathy, which has prognostic significance, in 24–72% of patients.

Treatment

Radical radiotherapy is the treatment for choice of SPB and SEP (Box 21.7). There is no role for surgery in SPB in the absence of structural instability or neurological compromise. Patients who need surgery receive postoperative radiotherapy. There is no data to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy. Some consider chemotherapy for patients at high risk of failure (e.g. tumour >5 cm).

Box 21.7

Treatment of solitary plasmacytoma

Surgery is avoided in head and neck SEP. Surgery may be considered for SEP at other sites. After a complete excision, radiotherapy may not be necessary and patients with incomplete excision require radiotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy may be considered for tumours of >5 cm and high-grade tumours.

Myeloma

Clinical features

Imaging

A skeletal survey reveals lytic bone lesions in myeloma (Figure 21.9). CT and/or MRI studies are indicated when symptomatic areas show no abnormality on routine radiographs.

Bone marrow

A unilateral bone marrow aspirate and trephine is indicated in all patients with myeloma which will show ≥10% clonal bone marrow plasma cells.

The diagnostic criteria of myeloma is shown in Box 21.8.

Box 21.8

Diagnostic criteria of myeloma

Myeloma is diagnosed by the following three criteria:

Staging

An International Staging System (ISS) has replaced the Durie–Salmon staging (Table 21.8).

| Stage (% of patients) | Criteria | Median survival (months) |

|---|---|---|

| I (29) |

Treatment

Myeloma is rarely curable and a minority of patients achieve long-term remission following allogenic stem cell transplantation. Chemotherapy is indicated for symptomatic myeloma and asymptomatic myeloma with myeloma-related organ damage. The median time to progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic myeloma is 12–32 months. Monitoring of asymptomatic myeloma includes 3-monthly clinical assessment and measurement of paraprotein.

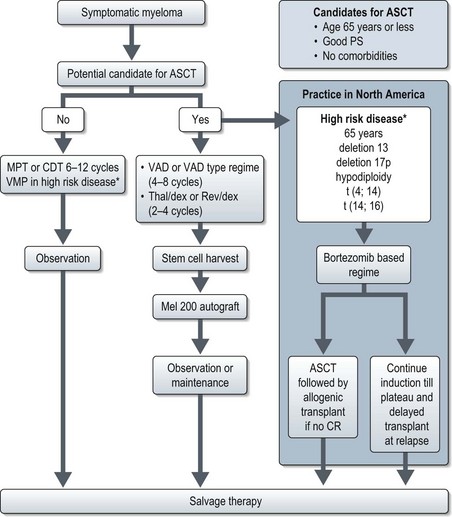

Treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma is rapidly evolving. The North American approach involves risk categorization of patients based on molecular cytogenetics and upfront use of novel agents such as bortezomib (a proteasome inhibitor) and lenalidomide (an analogue of thalidomide) whereas such an approach is yet to be adopted in the UK (Figure 21.10). Table 21.9 shows regimes in newly diagnosed myeloma. Treatment response is assessed by the International Myeloma Working Group definitions of response criteria.

| Regimen | Response rate |

|---|---|

| Regime for patients not eligible for ASCT | |

| Melphalan–prednisolone–thalidomide (MPT) | 75% |

| Bortezomib–melphalan-prednisone (VMP) | 70% |

| Cyclophosphamide–dexamethasone–thalidomide (CDT) | 72% |

| Regime for patients eligible for ASCT | |

| Vincristine–Adriamycin–dexamethasone (VAD) | 52% |

| Thalidomide–dexamethasone (Thal/Dex) | 65% |

| Lenalidomide–low dose dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) | 70% |

| Bortezomib–dexamethasone (Vel/Dex) | 80% |

| Bortezomib–thalidomide–dexamethasone (VTD) | 90% |

In patients eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) prolonged melphalan based chemotherapy can interfere with adequate stem cell mobilization and is therefore avoided. Patients not eligible for ASCT are treated with melphalan-based regimes (Figure 21.2 and Table 21.9). MPT is the preferred regimen for standard-risk patients who are not candidates for transplantation. ASCT prolongs the median overall survival in myeloma by approximately 12 months.

Supportive care

Evens AM, Hutchings M, Diehl V. Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma: the past, present, and future. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:543-556.

Peggs KS, Anderlini P, Sureda A. Allogeneic transplantation for Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:468-480.

Diehl V, Fuchs M. Early, intermediate and advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma: modern treatment strategies. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 9):ix71-79.

Lenz G, Staudt LM. Aggressive lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1417-1429.

Zucca E. Extranodal lymphoma: a reappraisal. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(Suppl 4):iv77-80.

Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894-1907.

Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Baccarani M. Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2007;370:342-350.

Shanafelt TD, Kay NE. Combination therapies for previously untreated CLL. Lancet. 2007;370:197-198. 21

Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2009;33:7-64.

thorax)

thorax)

of cases are due to two specific subtypes: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.

of cases are due to two specific subtypes: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma.