12 Cancers of the genitourinary system

Cancer of the kidney

Aetiology

Risk factors for renal carcinoma are as follows:

Pathology

Investigations and staging

Imaging

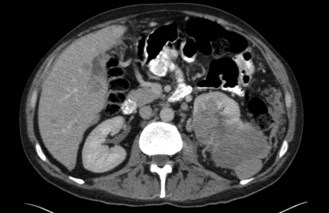

CT scan: CT scan appearance (Figure 12.1) is important in determining the appropriate surgical procedure – laparoscopic, partial or radical nephrectomy. Size is important in diagnosis – benign cortical adenomas can look like malignancies but tend to be less than 3 cm in diameter.

Staging

Stage (Table 12.1) determines the prognosis and treatment of renal tumours.

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 M0 |

Management

Surgery of the primary tumour

Palliative

Nephrectomy should also be considered as a palliative procedure in patients with metastatic disease. Although very rarely (<1%) this may result in regression of metastases (‘abscopal effect’), it is not the main reason for considering surgery. It is aimed mainly at reducing symptoms such as pain, haematuria and hypercalcaemia. Removal of the tumour bulk may also improve the efficacy of any subsequent systemic treatment – trials have shown that patients with metastatic disease who are treated with interferon have improved survival if they undergo palliative nephrectomy prior to the immunotherapy.

Metastatic disease

Interferon-alpha

Interferon has significant side effects (Box 12.1) that impact on quality of life. These effects are dose dependent, but the majority tend to stop quickly on discontinuation of treatment. Common side effects include fatigue, flu-like symptoms, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, bone marrow suppression and rash at injection site.

Novel agents

Sorafenib and sunitinib are oral multiple kinase inhibitors affecting VEGF, PDGF and c-KIT tyrosine kinases among others (p. 370). They have both antiproliferative and antiangiogenic activity. A phase III trial of sorafenib versus placebo in metastatic RCC patients on second-line systemic therapy showed an improvement of progression-free survival (5.5 months versus 2.8 months respectively).

Cancers of the urinary bladder and renal pelvis

Aetiology

Investigations and staging

Investigations

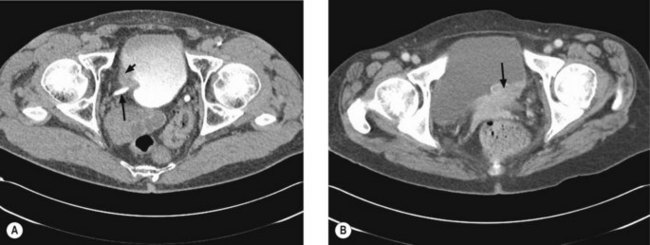

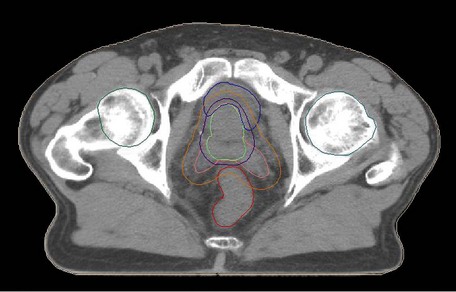

Once a bladder tumour is confirmed further investigations should be considered, including blood tests (renal function, full blood count, liver function and calcium level), chest X-ray, histology review and for muscle-invasive tumours, CT or MRI scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 12.2). MRI is better for showing early invasion of adjacent organs and extravesical spread. A bone scan is only necessary if indicated by symptoms or a raised alkaline phosphatase. Chest X-ray or CT chest is useful to rule out metastatic disease (Figure 12.3).

Management

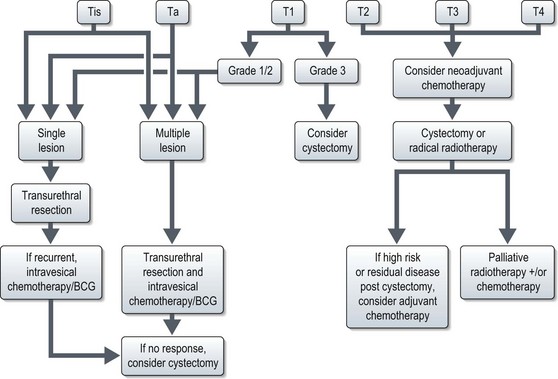

The management of bladder tumours is dependent upon the degree of invasion into the bladder wall and the histological grade of the cancer. Superficial, non-muscle invasive tumours are generally treated by transurethral resection, with intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy for multiple or recurrent tumours. Localized muscle invasive disease is treated by primary cystectomy or radiotherapy to the bladder and perivesical tissues. Figure 12.4 shows the management of bladder tumours by tumour stage. Indications for radical cystectomy are shown in Box 12.1.

Intravesical therapy

Muscle invasive disease

Radical cystectomy

Techniques for urinary diversion:

Radical radiotherapy

Radical radiotherapy is typically CT-planned with a target volume including a 1.5–2 cm margin around the empty bladder, prostatic urethra and tumour extension. This margin is to allow for considerable bladder movement. The rectum and femoral heads should be identified as organs at risk. Treatment is usually delivered via a 3-field plan (anterior and two laterals) to a dose of 55 Gy in 20 fractions over 4 weeks or 64 Gy in 32 fractions over 6.5 weeks using 6–10 MV photons.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy in metastatic disease

Response rates of 40–70% have been observed with combinations such as CMV (cisplatin, methotrexate, vinblastine) and MVAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin, cisplatin). Newer combinations such as gemcitabine and cisplatin have similar response rates and survival outcomes, with less toxicity (Box 12.2). Single agent platinum regimes are less effective (response rates of 30%).

Box 12.2

Chemotherapy regimes in bladder cancer

| Gem/Cis: | Gemcitabine – 1 g/m2 Day 1, 8, 15 |

| Cisplatin* 70 mg/m2 Day 1 | |

| Repeat every 28 days (or 21 days omitting day 15 gemcitabine) | |

| CMV: | Cisplatin* 100 mg/m2 Day 2 only (70 mg/m2 if palliative) |

| Methotrexate 30 mg/m2 Day 1 and 8 | |

| Vinblastine 4 mg/m2 Day 1 and 8 | |

| Repeat every 21 days | |

| MVAC: | Methotrexate 30 mg/m2 Day 2, 15, 22 |

| Vinblastine 3 mg/m2 Day 2, 15, 22 | |

| Adriamycin 30 mg/m2 Day 2 | |

| Cisplatin* 70 mg/m2 Day 2 | |

| Repeat every 28 days |

* For patients with poor renal function (creatinine clearance of 30–60 ml/min), consider replacing cisplatin with carboplatin (AUC 4–5).

Management of carcinomas of the renal pelvis and ureter

The staging of tumours of the renal pelvis and ureter is given in Table 12.3. Renal pelvic and upper urothelial transitional carcinomas are treated by radical resection of the kidney and ureter. Nephron-sparing procedures can be undertaken in small, localized tumours if there are concerns about function of the remaining kidney. Adjuvant radiotherapy confers no survival advantage following complete resection, but may be considered in patients with positive margins or residual local disease. Doses are limited by surrounding structures, but typically 45–50.4 Gy in 25–28 fractions can be delivered. There is some evidence to suggest that the addition of concurrent cisplatin chemotherapy to radiotherapy improves overall and disease-free survival in T3/4 and/or node-positive disease following surgical resection. The majority of relapses are distant, so systemic adjuvant therapy using platinum-containing chemotherapy regimes should be considered, although there is little published data as to the benefits of this approach. The current evidence for adjuvant chemotherapy is stronger for node positive disease than for locally advanced but node negative disease.

Table 12.3 Staging of tumours of the renal pelvis and ureter

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 M0 | Tumour invades subepithelial connective tissue |

| II | T2 N0 M0 | Tumour invades muscularis |

| III | T3 N0 M0 | Tumour invades peripelvic (or periureteric) fat or renal parenchyma |

| IV | T4 | T4 Invades adjacent organs or perinephric fat |

| or N1–3 |

Survival

| Stage | 5-year survival |

|---|---|

| Ta, T1, CIS | 70–95% |

| T2 | 50–80% |

| T3a | 40–70% |

| T3b | 20–50% |

| T4 | 10% |

Cancer of the prostate

Aetiology

The exact aetiology is not known and there are various suggested risk factors such as a high fat diet, anabolic steroids, oestrogen exposure and genetic. A hereditary prostate cancer gene on chromosome 1p has been identified. Mutation of the androgen receptor domain may be associated with high grade disease, extraprostatic extension and distant metastases. Mutation of the vitamin D receptor gene may also play a role. There is a link with BRCA genes as well.

Pathology

The Gleason grading system, an important prognostic factor, describes the degree of differentiation of the malignant cells (Box 12.3). Each tumour is graded twice, each out of five to give a total score out of 10 – the first grade relates to the most commonly observed pattern (primary pattern) and the second to the next most common pattern.

Presentation

The strongest predictors of metastasis are a high PSA, high Gleason score (8–10) and age >70 years. The Roach formulae (based on Partin’s tables) are commonly used in treatment algorithms to predict the risk of local extension and lymph node spread (Box 12.4).

Box 12.4

Roach formulae

| Risk of lymph node involvement (%): | 2/3 PSA + 10 (Gleason-6) |

| Risk of seminal vesicle involvement (%): | PSA + 10 (Gleason-6) |

| Risk of extracapsular extension (%): | 3/2 PSA + 10 (Gleason-3) |

Investigations and staging

If cancer is confirmed, further investigations are determined by the grade, volume of disease and PSA level, but may include a pelvic MRI scan to define extracapsular spread and seminal vesicle or lymph node involvement (generally offered to patients with Gleason 4+3 disease or above, or with PSA >20 ng/ml, in whom radical treatment is being considered) and a bone scan (if PSA >10–15 ng/ml). If there is doubt over lymph node involvement, a laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy might be considered prior to proposed radical treatment.

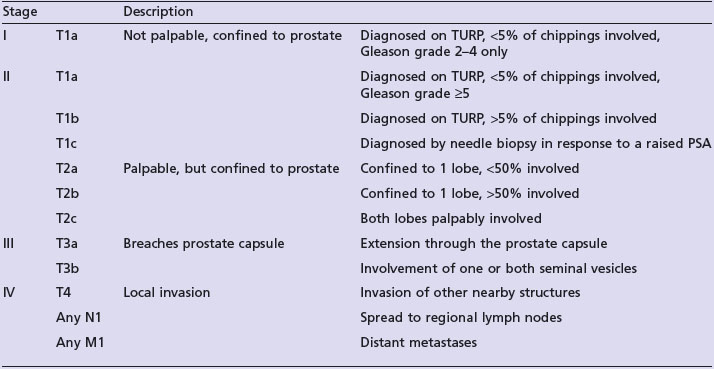

Table 12.4 shows the staging of prostate cancer.

Management of localized disease

The treatment options for localized disease are:

Active surveillance and watchful waiting

Many patients will have slow-growing disease which may have little or no impact on their life-expectancy, and they might therefore be spared the toxicities and inconvenience of radical treatment. Active surveillance implies close monitoring with early curative treatment offered to patients who show signs of progression. There are no absolute criteria for considering active surveillance and the decision should be made with the patient, but typical parameters would be T1–T2b disease, Gleason grade ≤7, PSA ≤15 (with favourable kinetics). A surveillance programme might consist of 3-monthly visits for the first 2 years, followed by 6-monthly visits thereafter, with a DRE and PSA checked at each visit. Repeat transrectal biopsies should be performed at 18 months. Criteria for consideration of radical treatment would be PSA progression (doubling time <2 years), clinical progression or upgrading of the Gleason score on repeat biopsy.

Radical treatment

External beam radiotherapy

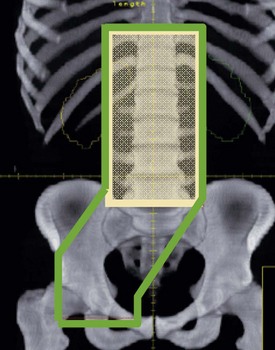

Conformal CT planning is well established in prostate radiotherapy (Box 12.5 and Figure 12.5). The Medical Research Council RT01 study randomized between 64 Gy and 74 Gy and found a hazard ratio for biochemical progression free survival of 0.67 (CI 0.53–0.85; p = 0.0007) in favour of the escalated group. However this was achieved at the expense of increased late bowel and bladder toxicity. It is not yet known whether there will be any improvements in overall survival.

Box 12.5

Radiotherapy for prostate (see Figure 12.5)

Acute side effects of radiotherapy include dysuria, frequency, diarrhoea, lethargy and erythema. Late effects include proctitis (diarrhoea, rectal bleeding, tenesmus: 30% mild, 5% severe), impotence (30–40%) and urinary incontinence (1–5%).

Brachytherapy

High-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy

HDR brachytherapy is suitable for intermediate-high risk patients. It is typically given as a boost following a shortened course of external beam radiotherapy but can also be used as monotherapy. Treatment is delivered through catheters implanted with ultrasound guidance into the prostate under general anaesthetic. HDR boost patients are typically treated in two or three fractions, 12 hours apart, necessitating overnight stay with the catheters and template in-situ. Box 12.6 shows some of the HDR boost schedules currently in use.

Box 12.6

High-dose rate brachytherapy boost schedules

| External beam dose and fractionation | HDR brachytherapy boost dose and fractionation |

|---|---|

| 35.7 Gy in 13 | 17 Gy in 2 |

| 46 Gy in 23 | 16.5 Gy in 3 |

| 46 Gy in 23 | 17 Gy in 2 |

| 50 Gy in 25 | 18 Gy in 2 |

| 45 Gy in 23 | 16.5 Gy in 3 |

| 46 Gy in 23 | 23 Gy in 2 |

Role of hormones in curative treatment

Prolonged adjuvant treatment for 2–3 years should be offered to all patients with high risk disease (Gleason 8–10, clinical T3/4 tumours or lymph node risk >30%). The role in low and intermediate risk patients is being assessed in randomized studies, but these patients are currently treated with 3–6 months of LHRH analogues before and during radiotherapy.

It should be noted that LHRH analogues are not without side effects (see Box 12.7) and can add considerably to the morbidity of patients undergoing radiotherapy.

Management of locally advanced and metastatic disease

Locally advanced disease

For patients with locally advanced disease radical radiotherapy or surgery may add little or no additional benefit over hormone therapy alone, although there is emerging evidence that radiotherapy does improve biochemical control in patients with PSA levels up to 70 ng/ml. The mainstay of treatment is with LHRH analogues or anti-androgens. Prolonged treatment with LHRH analogues results in significant toxicity due to reduction of testosterone levels (see Box 12.7). Androgen receptor inhibitors, such as bicalutamide, or 5-alpha reductase inhibitors effectively reduce the delivery of testosterone to the prostate without reducing serum testosterone levels and therefore tend to have a better side effect profile, although they can cause significant gynaecomastia. Prophylactic radiotherapy to the breast buds or prophylactic tamoxifen 10–20 mg/day can reduce and sometimes prevent the painful gynaecomastia. Typical radiotherapy doses are 8–10 Gy in a single fraction or 15 Gy in three fractions given on alternate days, using electron radiotherapy delivered to an 8–10 cm circle around each nipple.

Metastatic disease, elderly and those with significant comorbidities

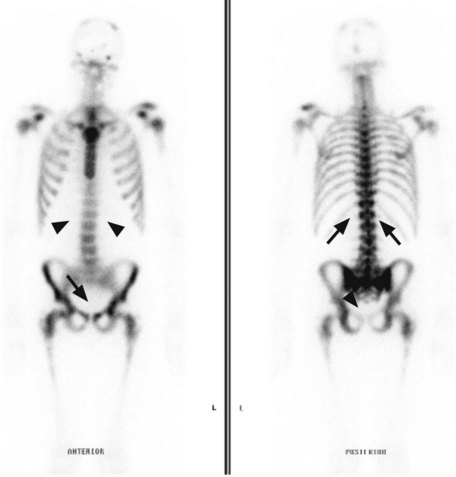

Metastatic disease (Figure 12.6) is generally treated with endocrine therapy, usually LHRH analogues in the first instance, with the addition of an anti-androgen to give maximal androgen blockade on biochemical or clinical progression. The typical duration of response to first line endocrine therapy with LHRH analogues is 18–24 months. There is increasing interest in intermittent LHRH analogue therapy as a way of prolonging the useful lifespan of the drug and of allowing patients to have periods of time off treatment and therefore avoid some of the side effects. Typical schedules are to treat until PSA falls below 4 ng/ml (or <80% of initial value) and restart when PSA rises above 10 ng/ml. Studies have shown no difference in survival when compared with continuous therapy, but significant improvements in quality of life, with patients spending a median of 1 year off treatment.

Management of relapse after radical treatment

Some authorities advocate postoperative radiotherapy to the prostatic bed in cases with a positive margin at radical prostatectomy, whilst others would wait and offer radiotherapy if the PSA fails to completely suppress or subsequently rises. In these situations, salvage radiotherapy is most effective if given before the PSA reaches a value of 2 ng/ml (Box 12.5).

Palliative treatment

Cancer of the testes

Investigations and staging

Preoperative investigations should include testicular ultrasound, chest X-ray and tumour markers including alpha-foetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-HCG) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). One or more tumour marker is raised in 75% of teratomas and 35% of seminomas. If AFP is raised or beta-hCG is >200, then treat as a non-seminomatous germ cell tumour (NSGCT). Tumour markers should be done preoperatively and repeated a minimum of 7 days after orchiectomy.

The staging and risk classification of testicular cancer is shown in Tables 12.5 and 12.6.

| Stage 0 | T1sN0M0 – intracellular germ cell neoplasm |

| Stage IA | pT1N0M0 – tumour limited to testis and epididymis with no LVI or tunica vaginalis invasion (TVI) |

| Stage IB |

Table 12.6 International Germ Cell Consensus Classification prognostic criteria for non-seminomatous tumours

| Good prognosis | Intermediate prognosis | Poor prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Testis or retroperitoneal primary | Testis or retroperitoneal primary | Mediastinal primary site |

| No non-pulmonary visceral metastases | No non-pulmonary visceral metastases | Non-pulmonary visceral metastases |

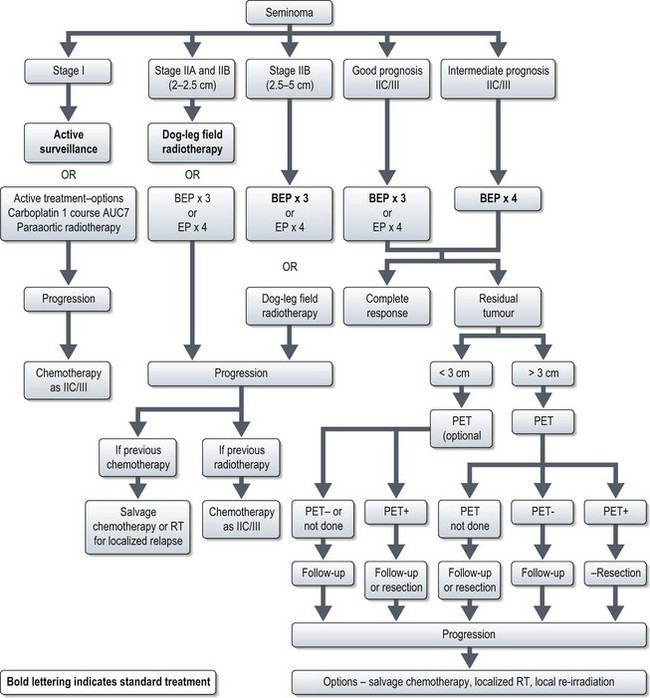

Postoperative management of seminoma (Figure 12.7)

Stage I disease

Around 80% of patients with seminoma present with stage I disease and survival is >99%. There are two risk factors for recurrence: rete testis invasion and tumour size of >4 cm. 5-year relapse rate is 12% with no risk factors, 16% with one factor and 32% with both factors. Current treatment is active surveillance irrespective of risk factors. If surveillance is not an option the active treatment options are a single dose of carboplatin (AUC7) and para-aortic radiotherapy (20 Gy in 10 fractions) (Box 12.9).

Stage II–IV disease

Clinical stage IIA disease should be verified beyond imaging (e.g. needle biopsy) before systemic treatment. Standard treatment for stage IA and stage IB with 2–2.5 cm node is radiotherapy to para-aortic and ipsilateral iliac nodes (‘dog leg field’). An alternative option is three cycles of PEB chemotherapy (3 or 5-day schedule). Treatment option of stage IIB with 2.5–5 cm node is three courses of PEB (Box 12.8).

The treatment of stage IIC/III is three cycles of PEB for good prognosis patients (3 or 5-day schedule) and four cycles for intermediate prognosis patients (5-day schedule). Three cycles of PEB may be substituted by four cycles of PE in cases of increased bleomycin toxicity.

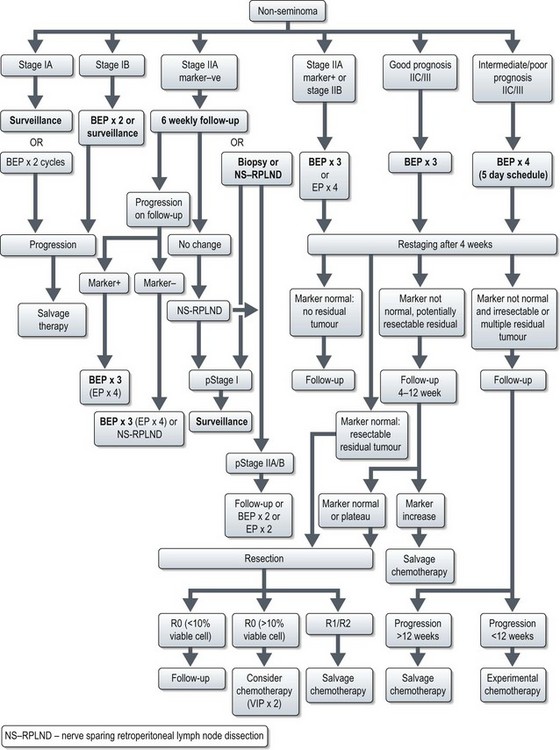

Postoperative management of non-seminomatous germ cell tumours (NSCGTs) (Figure 12.9)

Stage I patients are divided into low (20% relapse rate) and high risk (40–50% relapse) based on absence or presence of vascular invasion. The management is outlined in Figure 12.9. Treatment choice is based on toxicity, tumour burden and patient preference. Active surveillance is intense follow up with frequent clinical examination, tumour marker estimation and scans. Frequency of follow-up depends on risk of relapse.

Management of stage IIA–III disease is outlined in Figure 12.9. It is important that in patients undergoing chemotherapy, dose intensity is maintained (Box 12.8, see also Box 4.3).

Cancer of the penis

Pathogenesis and pathology

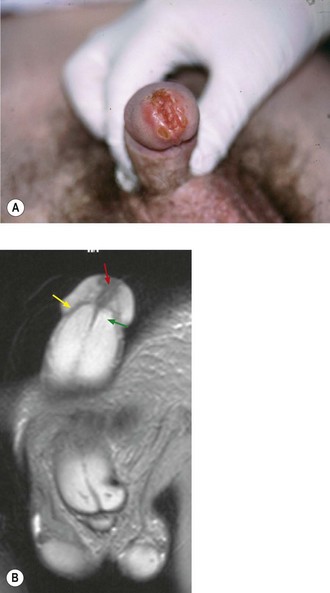

Investigations and staging

Diagnosis is made by biopsy of the lesion. Investigations should include a full blood count, urea and electrolytes and liver function. The inguinal, pelvic and abdominal lymph nodes should be assessed with a CT or MRI scan. Clinically enlarged inguinal nodes can be assessed with fine needle aspiration or biopsy. A MRI of the pelvis with an artificial erection may be useful in assessing cavernal invasion (Figure 12.10). A chest X-ray is usually sufficient for distant staging unless there is suspicion of disease elsewhere. It is sensible to photograph the lesion prior to treatment for future reference. The staging of penile cancers is shown in Table 12.7.

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 | Invasion of sub-epithelial tissue |

| II | T2 N0 | Invasion of corpora or cavernosum |

| T1/2 N1 | Single superficial inguinal lymph node involvement | |

| III |

Management

Management of the primary tumour

Invasive disease

External beam radiotherapy

If disease is limited to the glans, treatment is with electron-beam radiotherapy with a 2 cm margin around the tumour. Perspex or bolus is placed over the cut-out section to ensure that the skin surface dose is 100%. For more extensive disease, photon irradiation is appropriate. Two lateral fields are applied with the penis placed between two halves of a wax block. The testis and groin are shielded with lead. The conventional dose is 60–64 Gy in 30–32 daily fractions using 4–6 MV photons. If there is residual disease following radiotherapy, surgical excision should be considered as a salvage treatment. Box 12.10 lists the side effects of penile radiotherapy.

Box 12.10

Side effects of radiotherapy to the penis

| Early | Mucositis |

| Oedema of the prepuce | |

| Local infections | |

| Dysuria | |

| Difficulty with micturition | |

| Late | Telangiectasia |

| Superficial necrosis | |

| Urethral meatal stenosis | |

| Deep fibrosis | |

| Loss of sexual function |

Brachytherapy

Patients who recur after brachytherapy are salvaged with surgery.

Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet.. 2009;373:1119-1132.

Rini BI. New strategies in kidney cancer: therapeutic advances through understanding the molecular basis of response and resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1348-1354.

Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Feldman AS. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:239-249.

Damber JE, Aus G. Prostate cancer. Lancet. 2008;371:1710-1721.

Horwich A, Shipley J, Huddart R. Testicular germ-cell cancer. Lancet. 2006;4(367):754-765.

Pliarchopoulou K, Pectasides D. Late complications of chemotherapy in testicular cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:262-267.

Pagliaro LC, Crook J. Multimodality therapy in penile cancer: when and which treatments? World J Urol. 2009;27:221-225.