11 Cancers of the gastrointestinal system

Oesophageal cancer

Aetiology

Box 11.1 shows risk factors for oesophageal cancer. A diet rich in fruit and vegetables has been shown to reduce the relative risk.

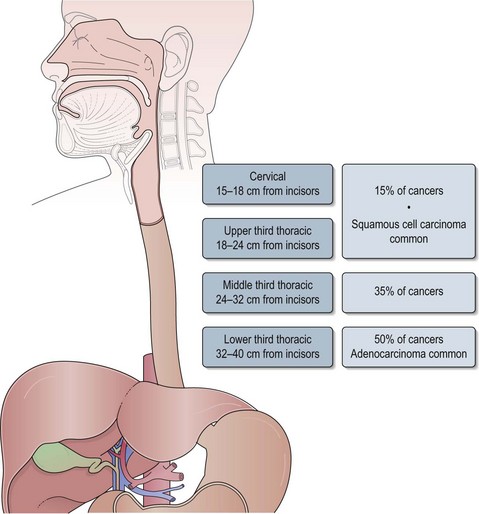

Anatomy

The oesophagus extends from the cricopharyngeal sphincter to the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) and is 25 cm in length. Figure 11.1 shows the anatomic sections of the oesophagus. The majority of tumours (85%) arise in the middle and lower third of oesophagus and 15% arise in the upper third.

Clinical features

Metastatic disease can result in liver capsular pain, bony metastases, ascites or peritoneal deposits. Patients are usually cachectic at this stage.

Investigations and staging

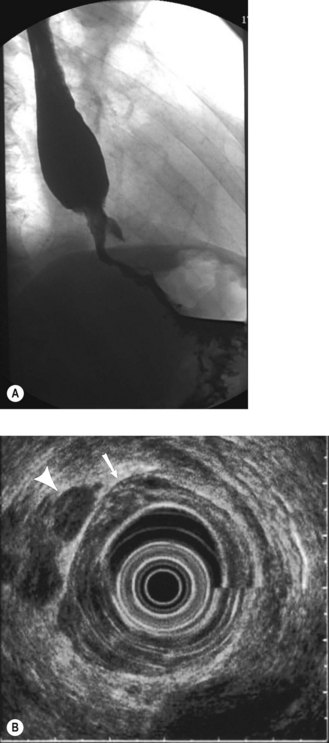

Investigations are aimed at establishing the extent of disease, obtaining histologic diagnosis and assessing fitness for appropriate treatment:

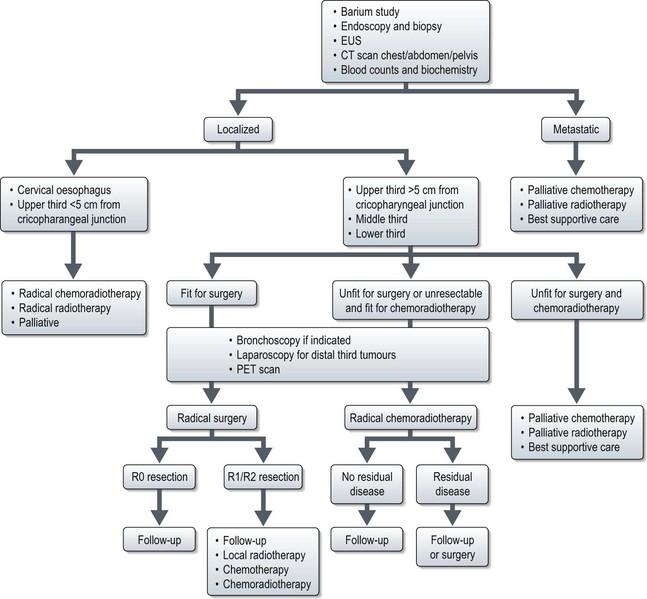

Management of oesophageal cancer (Figure 11.3)

Localized disease

Radical surgery

The common procedures are as follows:

Radical radiotherapy (Box 11.3)

Box 11.3

Radiotherapy for oesophageal cancer

Radical chemoradiotherapy (CRT)

Radiotherapy is given in combination with chemotherapy which is proven to be superior to radical radiotherapy alone. Chemotherapy improves local control by radiation sensitization and helps to minimize distant metastatic relapses. This approach results in an overall 3-year survival of 30%. The commonly used combination is cisplatin with 5-fluorouracil with radiotherapy at a dose of 50 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction (Box 11.3). However, locoregional recurrence remains the major cause for overall failure with 50% of patients developing locoregional disease. Attempts to increase the radiotherapy dose to improve local control has resulted in increased treatment-related deaths without improvement in local control or survival. Studies comparing CRT with CRT followed by surgery showed similar overall survival, but with high treatment-related mortality with surgery.

Preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery

A meta-analysis showed that preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery improved 2-year survival by 7% compared with surgery alone (HR 0.90; CI 0.81–1.00). The largest study (MRC OE02) of 802 patients which compared surgery alone with two cycles of 3-weekly preoperative cisplatin (80 mg/m2 on day 1 as 4 hour infusion) and 5-fluorouracil (1 g/m2/day continuous infusion for 4 days) followed by surgery showed that chemotherapy improves overall survival from 34% to 43% at 2-years (p = 0.004). Hence, this is the standard treatment option in most UK centres.

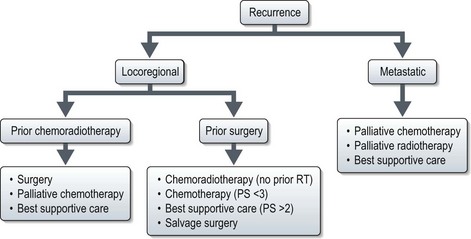

Advanced and recurrent disease (Figures 11.3 and 11.4)

Systemic treatment

Chemotherapy for advanced oesophageal cancer improves survival when compared to best supportive care alone. In the UK, the combination of epirubicin, cisplatin and 5FU (ECF) has been used as the standard regime (Box 11.4). A randomized study (REAL-2) to explore the role of oxaliplatin instead of cisplatin and capecitabine instead of 5-FU (EOX regime) showed that toxicity of 5FU and capecitabine were similar; oxaliplatin resulted in increased neuropathy and diarrhoea but reduced renal toxicity, thromboembolism, alopecia and neutropenia when compared with cisplatin. Patients receiving EOX survived longer than ECF (38% vs. 47% at 1-year; p = 0.02).

Palliative treatment of dysphagia

Gastric cancer

Epidemiology

Only 20% of patients present with localized disease and the overall 5-year survival is 15–20%.

Aetiology

The aetiology of gastric cancer is multifactorial. The following factors increase the risk:

Pathology

Investigations and staging

Further assessment

Staging

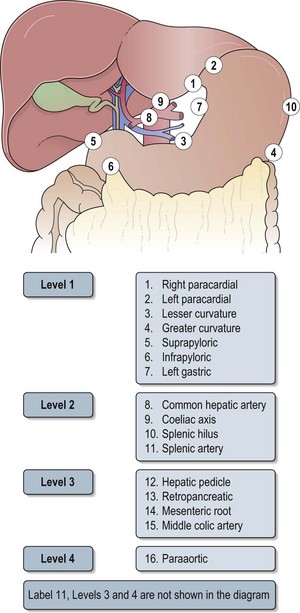

Box 11.5 shows the pathological staging of gastric cancer. Sixteen nodal stations defined by the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer help to define the extent of lymph node dissection in gastric cancer (Figure 11.6 and see below).

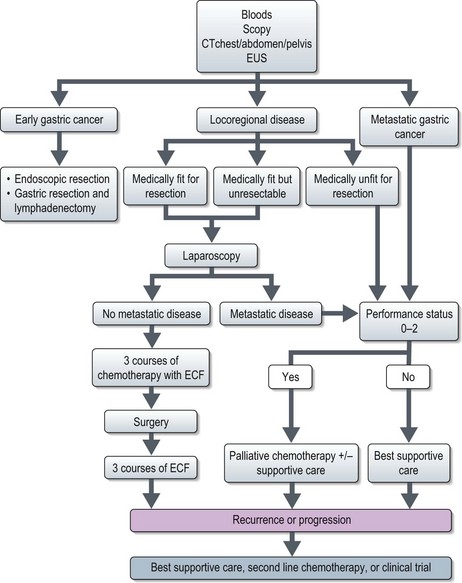

Management of gastric cancer (Figure 11.7)

All patients should be assessed in a multidisciplinary setting. Assessment of the performance status and co-morbidities should be done.

Early gastric cancer (EGC)

Resectable gastric cancer

Surgery

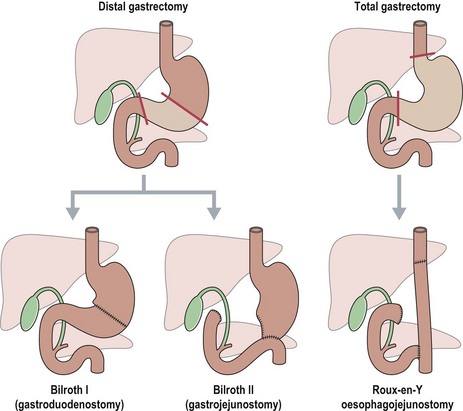

The extent of gastric resection depends on the size and location of the primary tumour (Figure 11.8).

Perioperative treatment

A randomized study (UK MRC MAGIC) showed that three cycles of pre- and postoperative chemotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin and continuous infusion 5 fluorouracil (ECF) significantly improved 5-year survival (36% vs. 23%; p = 0.009) compared with surgery alone in resectable gastric and lower oesophageal cancers (Box 11.6). This is the standard of care in most of the UK and parts of the Europe (Box 11.6).

Box 11.6

Treatment regimes in gastric cancer

Unresectable gastric cancer

Systemic treatment of unresectable gastric cancer

Patients with unresectable and/or disseminated gastric cancer should be considered for a clinical trial, and those with good performance status (0–2) may be offered systemic therapy. Randomized trials suggest that chemotherapy may improve survival compared with best supportive care (9–11 months vs. 3–4 months HR 0.39) and quality of life. A meta-analysis showed that combination chemotherapy improves survival by 6 months and the best survivals are achieved by three-drug regimens containing 5-FU, anthracycline and cisplatin. The standard regime used in the UK is ECF (Box 11.6). A recent study (REAL 2) showed that ECF is comparable to EOX. This regimen has the advantage of avoiding the need for continuous infusion of 5-FU.

Cancers of the liver

Aetiology

Diagnosis and staging

Staging

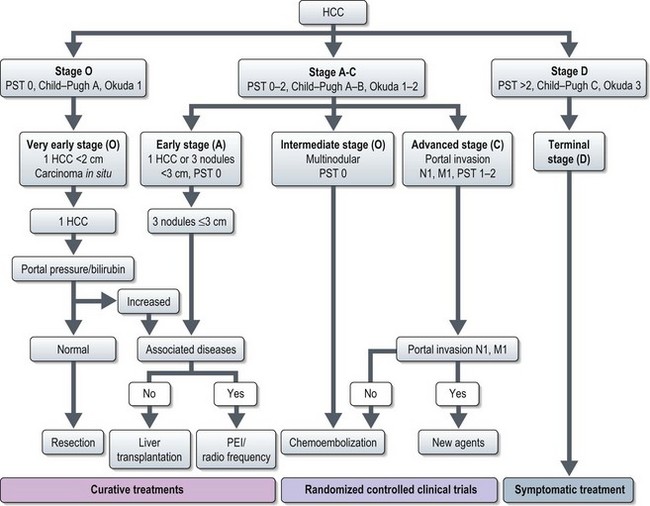

There are two methods of staging: TNM and Okuda staging. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer group incorporate Okuda staging (Box 11.7) for staging classification and treatment recommendation.

Box 11.7

Okuda staging of hepatocellular carcinoma

| Criteria | Positive | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor size* | >50 percent | <50 percent |

| Ascites | Clinically detectable | Clinically absent |

| Albumin | <3 mg/dL | >3 mg/dL |

| Bilirubin | >3 mg/dL | <3 mg/dL |

| Stage | |

|---|---|

| I | No positive |

| II | One or two positives |

| III | Three or four positives |

* Largest cross-sectional area of tumour to largest cross-sectional area of the liver.

Management (Figure 11.9)

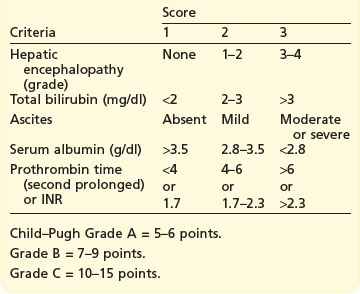

Treatment of HCC depends on tumour stage, liver function (Child–Pugh grading; Box 11.8), and performance status.

Figure 11.9 Staging classification and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

(Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. LANCET 2003;362;1907–1917, fig 5, with permission). PST – performance status test, PEI – percutaneous ethanol injection.

Stage O and stage A

Tumours of the biliary tract

Carcinoma of the gallbladder

Clinical presentation

The usual presentation is an incidental finding at cholecystectomy. Other clinical features are that of gallstone disease and unremitting jaundice in some patients.

Investigations and staging

Treatment

Patients with resectable cancer

Carcinoma of the bile ducts

Aetiology

Clinical features

Diagnosis of malignancy in patients with PSC is challenging. The new development of jaundice and a dominant bile duct stricture in an individual with previously stable PSC should raise the suspicion of malignancy.

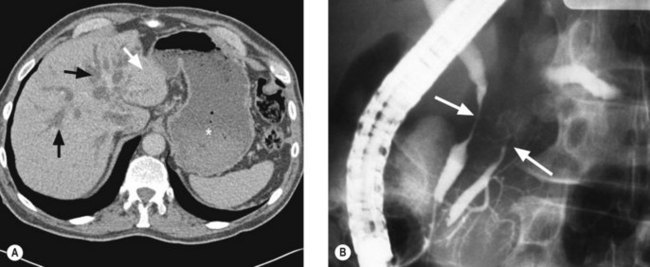

Diagnosis and staging

Imaging

Staging

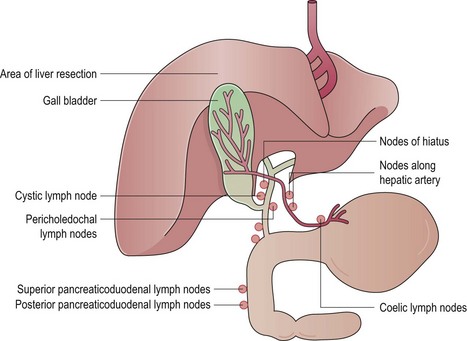

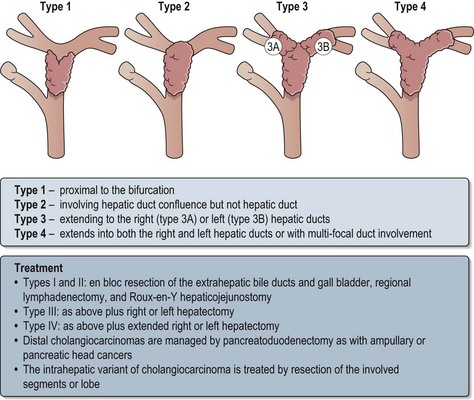

The Bismuth and Corlette classification of proximal bile duct cancers are shown in Figure 11.11.

New agents

Growth factor receptors HER-1 and HER-2 are overexpressed in biliary tract cancers. New agents studied include erlotinib (EGFR-1 inhibitor) and lapatinib (EGFR-1/HER-2 dual inhibitor) (p. 370).

Pancreatic cancer

Aetiology

Exact aetiology is unknown and the suggested risk factors include:

Clinical features

Tumours of the head of the pancreas tend to present with obstructive jaundice or acute pancreatitis, but the onset is usually insidious. Tumours of the body and tail tend to present even later and are associated with a worse prognosis. Other presenting features include fatigue, back pain, weight loss, late onset diabetes mellitus, steatorrhoea and duodenal obstruction.

Diagnosis and staging

Initial investigations include abdominal ultrasound and CT scan.

Further investigations include:

Management of pancreatic cancer

Treatment of resectable cancer

Surgery

Patients with good performance status and resectable tumours are treated with radical resection. Criteria for resectability are given in Box 11.11. Though the aim of surgery is a complete microscopic resection (R0), 30–60% of resections result in microscopic residual disease (R1). Patients with jaundice may be considered for pre-operative biliary drainage. The type of surgery depends on location of the tumour:

The postoperative morbidity of radical surgery is around 40% and the mortality is <5%.

Postoperative treatment

Unresectable and metastatic cancer

Symptom control

Pancreatic endocrine tumours

Clinical presentation is either due to tumour mass or from excessive peptide secretion.

Cystic tumours of pancreas

These constitute around 15% of all pancreatic cystic masses. The common types are:

Malignant tumours of the small intestine

Aetiology

Investigations

The initial investigations depend on the presenting symptoms.

Staging

Adenocarcinoma is staged similar to colonic cancer (p. 163). Lymphomas are staged using the Ann Arbor staging (p. 299).

Management

Small intestinal adenocarcinoma

Chemotherapy regime is same as that of colonic cancer (p. 165). A small study reports a response rate of 50% and a median survival of 20 months with a combination of oxaliplatin with capecitabine.

Colorectal cancer

Epidemiology

Over 80% of cases occur in people over 60 and is rare below the age of 40 (except in hereditary forms). The male:female incidence ratio is 1.2 : 1.0. In the UK, the lifetime risk is 1 in 18 for men and 1 in 20 for women. Two-thirds of primaries are in the colon and one third in the rectum. Left-sided cancers are more common than right (sigmoid and rectal cancers account for over half).

Aetiology

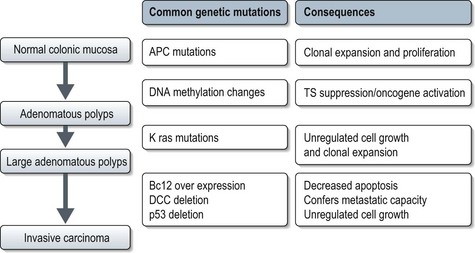

Pathogenesis and pathology

Almost all colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas and arise in adenomatous polyps through a multi-step process (Figure 11.13). Most adenocarcinomas are moderate to well differentiated with typical morphology. About 80% of primary colorectal adenocarcinomas and 70% of metastases will be CK7− CK20+. Rare histologic types include squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma and medullary carcinoma.

Presentation

About 85% of patients with bowel cancer have these symptoms at the time of diagnosis. Approximately one-third presents with altered bowel habit or obstructive symptoms (usually left sided tumours as the distal bowel is narrower and faecal content more solid) and one-third with iron deficiency anaemia (usually right-sided tumours). For rectal cancers other symptoms include faecal incontinence, passage of mucus and tenesmus. Up to 30% present with acute colonic obstruction. More advanced tumours may cause weight loss, nausea and anorexia, and abdominal pain and distension from ascites or hepatomegaly.

Investigations and staging

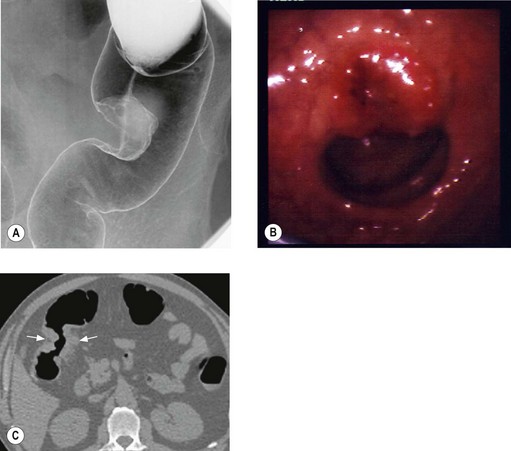

Initial investigations include double contrast barium enema (DCBE), sigmoidoscopy (allows visualization up to splenic flexure at 60 cm) and colonoscopy (Figure 11.14A & B). The whole colon should be imaged as approximately 5% of patients have synchronous cancers and up to 40% have synchronous adenomas. CT colonography is an alternative DCBE (Figure 11.14C). Endoscopy also allows biopsy confirmation.

Further investigations

Staging

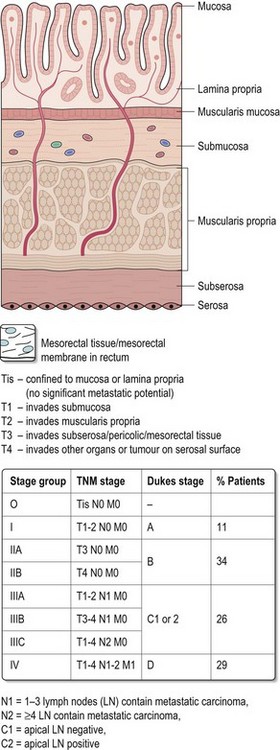

Figure 11.17 shows TNM and Dukes’ staging which are postoperative staging. After radical resections, 12 or more nodes should be examined as this correlates with prognosis for Dukes’ B cancers. Pathology reports should also inform about presence or absence of tumour perforation, extramural vascular invasion, radial margins, lymph nodes (number examined and involved) and assessment of completeness of resection.

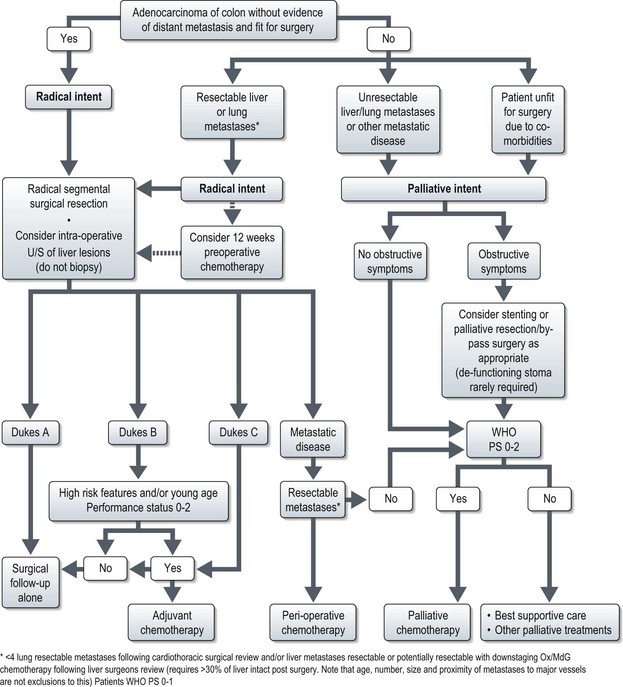

Management of colon cancer (Figure 11.18)

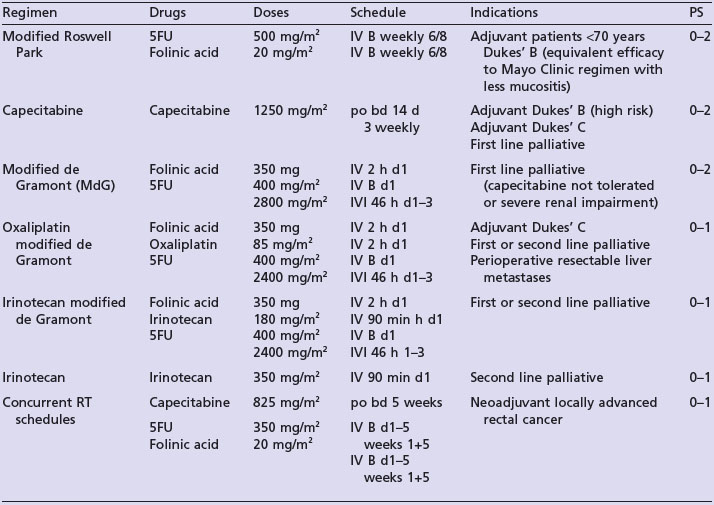

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Table 11.1 shows current recommendations for adjuvant chemotherapy. There is no benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in Dukes’ A disease. In stage III (Dukes’ C) disease, 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid (5FU/FA) chemotherapy gives an absolute survival benefit of between 8–13%, with 6 months chemotherapy as effective as 1 year. In stage II disease, chemotherapy results in a similar proportional reduction (approximately 33%) in recurrence, but absolute benefits are less because of lower mortality rates (QUASAR 1 showed an absolute increase in 5-year OS of 3.6% for patients less than 70 years). Patients with stage II disease with adverse features have a higher disease-related mortality rate (with >1 risk factor this approaches that of Dukes’ C cancers) and hence absolute benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy are greater.

Ideally chemotherapy should begin within six weeks of surgery dependent on wound healing and patient recovery. The benefit of adjuvant treatment starting beyond 3 months of surgery is uncertain.

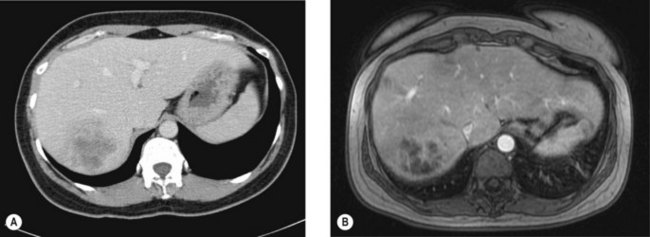

Management of isolated lung or liver metastases

Liver or lung metastasectomy should be considered in fit patients following radical resection of their primary disease (Figure 11.16). However, resection is feasible only in 10% of patients with metastatic disease. Preoperative chemotherapy, in selected patients whose liver metastases are initially extensive for surgery, can enable curative resection in about 30%. A maximum of 12 weeks treatment is recommended prior to surgery as both oxaliplatin and irinotecan are associated with liver parenchyma damage and the risks increase with higher cumulative chemotherapy doses.

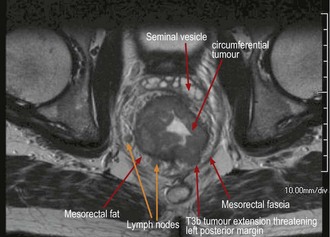

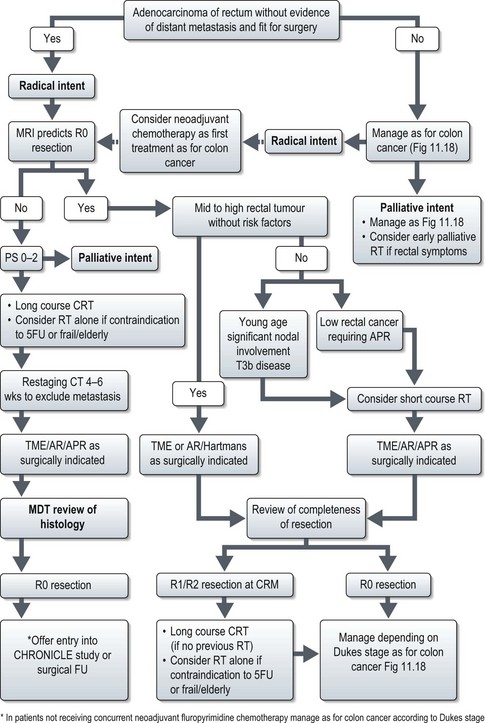

Management of rectal cancer (Figure 11.19)

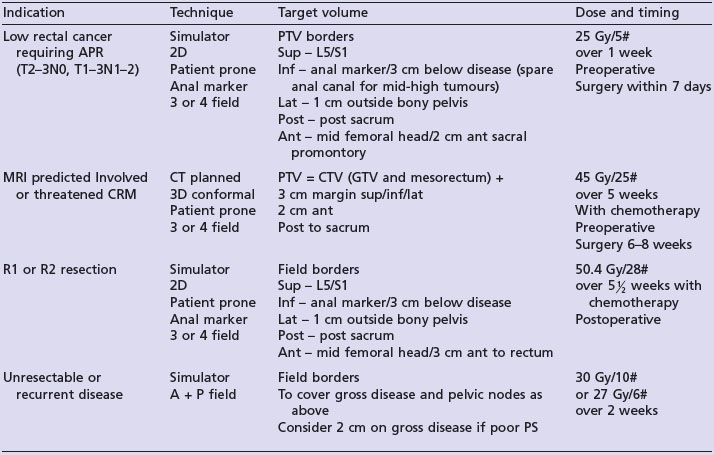

Radiotherapy (Table 11.2)

The accuracy of preoperative MRI staging in rectal cancer has led to a more selective approach to the use of RT in the UK with short course treatment being offered to those patients with predicted R0 resections but significant risk factors for relapse (Figure 11.19). Early reports from the MRC CR07 study show reduced LR rates (4.7% vs. 11.1%) for all stages and sites of rectal cancer with preoperative short course RT compared to selective postoperative RT if CRM was positive, and an improved 3-year DFS of 4.6%.

Local recurrence of rectal cancer

In selected cases exenteration (if not involving pelvic side walls or sacrum) may be curative. In these cases metastatic disease should be excluded by PET before committing patients to such morbid surgery. If preoperative CRT is previously not given, it should be used to decrease the risk of further recurrence. Re-irradiation is not a standard practice but may be considered in selected cases.

Palliation of colorectal cancer

Palliative chemotherapy

Fluropyrimidines improve median survival by approximately 4 months over best supportive care alone (10 vs. 6 months). The infusional regimen Modified de Gramont (MdG) and oral capecitabine have a response rate of approximately 30% and favourable toxicity profiles in comparison to other 5FU/FA regimes. The addition of either irinotecan or oxaliplatin to MdG or capecitabine as first line treatment increases response rates to 50–60% and median survival to 14–16 months at the cost of increased toxicities. The addition of second line treatment prolongs median survival to more than 20 months.

Prognosis and outcome

Stage is the most important prognostic factor. Stage-wise 5-year survival rates are >90% for stage I (Dukes’ A), 70–85% for stage II (Dukes’ B) without risk factors, 40–60% for stage II with risk factors and stage III (Dukes’ C) and 5% for stage IV disease. Median survival of inoperable metastatic disease is 6 months with best supportive care alone, 18–20 months with chemotherapy and over 2 years with targeted agents.

Anal cancer

NB Invasion of rectum, subcutaneous tissue, skin or sphincter muscles is not T4

Management

The treatment options for localized tumours are:

Treatment options for patients with stage IV disease are palliative chemotherapy, palliative radiotherapy and active symptom control.

Chemoradiation (CRT)

There are no RCTs of surgery versus CRT; but CRT offers sphincter preservation for the majority of patients. Chemoradiation using concurrent mitomycin C (MMC) and 5 FU is the standard of care for all stages of locoregional disease (Box 11.12). The UKCCCR ACT I and an EORTC study confirmed the benefit of CRT over RT alone in terms of reduction in locoregional failure, improvement in colostomy free and disease specific survival. Acute toxicities are increased by concurrent treatment, without significant increase in late morbidity.

Box 11.12

CRT for anal cancer

Radiation dose and technique

The dose of radiation concurrent with chemotherapy required to treat anal cancer is debatable.

Radical surgery

Patients with confirmed local relapse following CRT who are fit to consider salvage surgery should be restaged with CT chest and abdomen to exclude metastatic disease as well as MRI pelvis to stage regional disease. Approximately 50% can be cured by a salvage surgical resection, but local recurrence rates approach 50% even in patients undergoing complete resections. Inguinal node dissection similarly is reserved for patients with residual or recurrent inguinal metastases after CRT. It carries a high risk of postoperative wound complications and chronic lymphoedema.

Prognosis and survival

Size of the primary tumour, in the absence of metastases, is the most useful predictor of survival. Overall 5-year survivals are in the region of 75%. A lesion size of 4 cm represents the threshold for local control, with up to 95% of tumours ≤4 cm achieving complete pathological response to CRT (Table 11.4).

| T stage | 5-year OS % | 5-year local control % |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 80 | 90–100 |

| T2 | 70 | 75 |

| T3/4 | 45–55 | 55 |

Median survival of patients with distant metastases remains 9–12 months.

Mariette C, Piessen G, Triboulet JP. Therapeutic strategies in oesophageal carcinoma: role of surgery and other modalities. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:545-553.

Hartgrink HH, Jansen EP, van Grieken NC, van de Velde CJ. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:477-490.

Rampone B, Schiavone B, Martino A, Viviano C, Confuorto G. Current management strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3210-3216.

Eckel F, Jelic S, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Biliary cancer: ESMO clinical recommendation for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):46-48.

Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605-1617.

Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375:1030-1047.

Uronis HE, Bendell JC. Anal cancer: an overview. Oncologist. 2007;12:524-534.