13 Cancers of the female genital system

Epithelial ovarian cancer

Aetiology

Approximately 5–10% of ovarian cancer are familial, most of which are associated with BRCA1/BRCA2 gene mutations (90%) (p. 48). Women with a BRCA1 mutation have a 40% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer, and those with BRCA2 have an 18% lifetime risk. Women with HNPCC have a 10% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.

Pathogenesis and pathology

Pattern of spread

The most common pattern of spread is peritoneal. Lymphatic dissemination to the pelvic and para-aortic nodes occurs in advanced disease. Spread through the diaphragm can lead to pleural effusion, although some effusions may be reactive. Haematogenous spread to the liver or lung is unusual (2–3%).

Investigations and staging

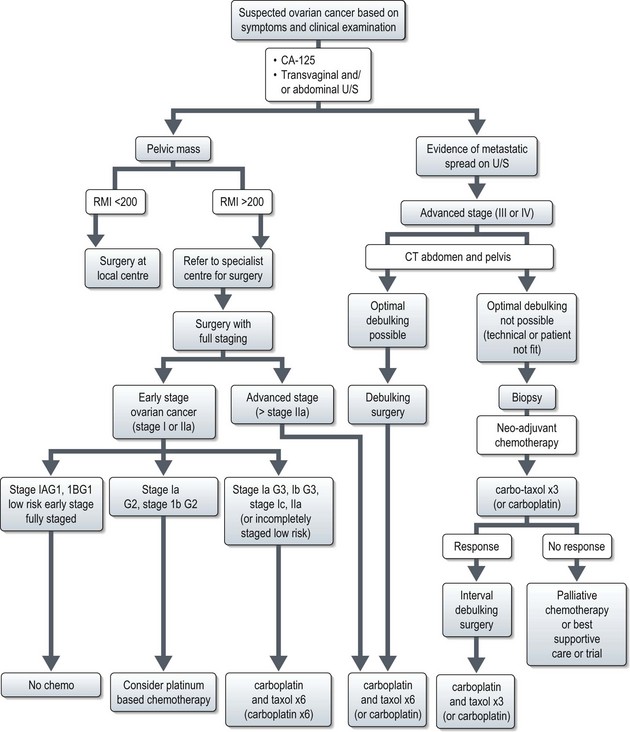

The risk of malignancy index (RMI) scoring system is used to predict whether a pelvic mass is malignant (Box 13.1). Women with an RMI of >200 should be referred to a specialist centre for further management and surgery. An RMI of >200 has a positive predictive value of 87% and a sensitivity of 88% for diagnosing malignant disease.

RMI score = ultrasound score × menopausal score × CA-125 level in U/ml.

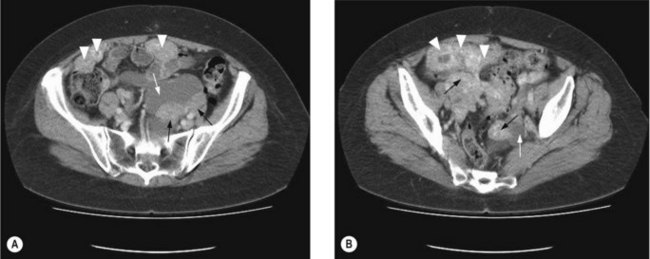

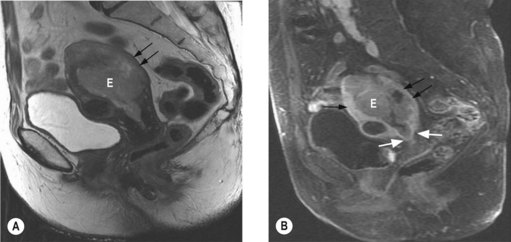

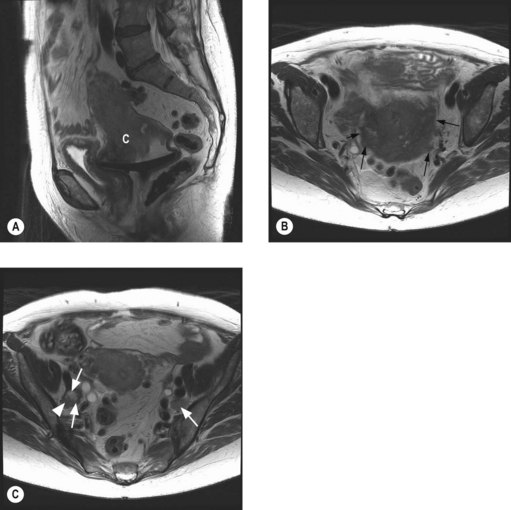

To assess operability patients should have a CT of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 13.1), and a CXR. In patients with a pleural effusion, cytological diagnosis is required to determine if the effusion is malignant.

Patients with ascites without a mass on CT, should have cytological and immunohistochemical analysis, in addition to CA-125, CEA and CA19-9 (p. 287). The immunohistochemical profile of an ovarian tumour is typically CK 7 positive and CK 20 negative. A serum CA125:CEA ratio >25 is strongly suggestive of an ovarian rather than a GI primary.

Staging

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging is shown in Box 13.2.

Box 13.2

FIGO staging of ovarian cancer

Stage I – limited to one or both ovaries

Stage III – microscopic peritoneal implants outside of the pelvis; or limited to the pelvis with extension to the small bowel or omentum

Stage IV – distant metastases to the liver or outside the peritoneal cavity

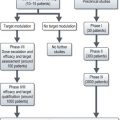

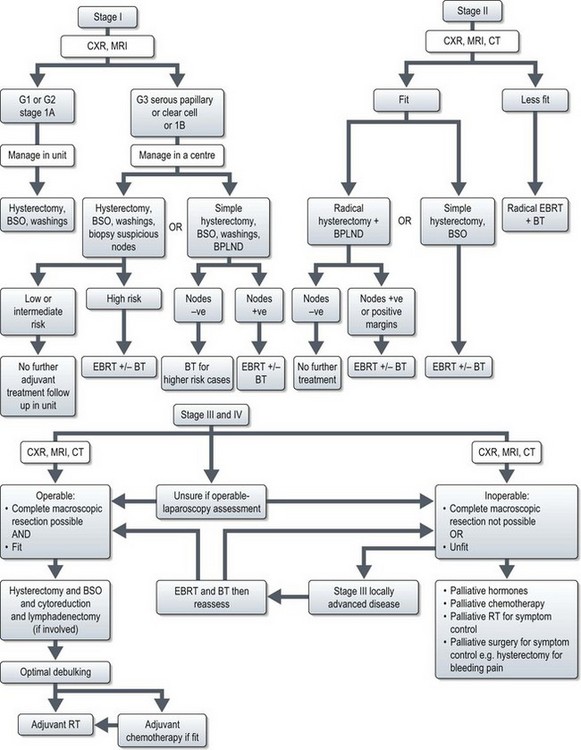

Management (Figure 13.2)

Early stage disease (stage I and II)

Surgery

Fertility preserving surgery

In younger patients with stage IA tumours and favourable histology, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging may be carried out, although data on fertility preserving surgery is limited. Endometrial biopsy should be carried out as a synchronous primary is present in 10% of patients. Wedge biopsy of the contralateral ovary should only be taken if it appears abnormal, as the probability of involvement of a macroscopically normal ovary is low (2.5%).

Chemotherapy

For patients with stage IA/B G1 non-clear cell cancer (low risk) 5-year disease free survival is >90% without chemotherapy if optimal surgery has been performed. For patients with high risk features (G3, clear cell, stage IIA disease), 5-year recurrence rates are 25–40% and adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended. In these patients, chemotherapy improves 5-year disease free survival (DFS) by 11% (from 65% to 76%), and 5-year overall survival (OS) by 8% (75% to 82%). Chemotherapy with 6 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel is recommended, although 6 cycles of carboplatin is also acceptable (Box 13.3). For stage I G2 tumours the role of chemotherapy is not clear but 6 cycles of carboplatin may be offered.

Advanced stage disease (stage III and IV)

Patients with advanced disease may develop medical complications as a result of their cancer, notably thrombosis which has consequences for further management (Box 13.4).

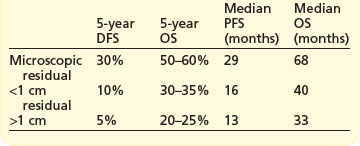

Surgery

The extent of cytoreductive surgery is the most important prognostic factor after stage. The aim of surgery is to achieve a complete macroscopic debulking, or failing this, an ‘optimal debulking’. The definition of ‘optimal debulking’ is visible residual tumour of <1 cm. Studies have shown that patients with residual >2 cm show no improvement in survival over patients without debulking, and are considered incurable. Outcomes according to cytoreductive surgery are shown in Box 13.5. However, even after a complete response 25–50% will recur later.

Prognosis

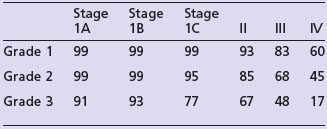

Prognosis according to stage is shown in Table 13.1. The most important prognostic variables after stage are in order; degree of differentiation, cyst rupture, substage of disease and age.

| FIGO stage | 5-year survival (%) | 5-year disease-free survival |

|---|---|---|

| I | 80–90 | 70–85 |

| II | 65–80 | 55–65 |

| IIIa | 50 | 45 |

| IIIb | 40 | 25 |

| IIIc | 30 | 20 |

| IV | 15 | 10 |

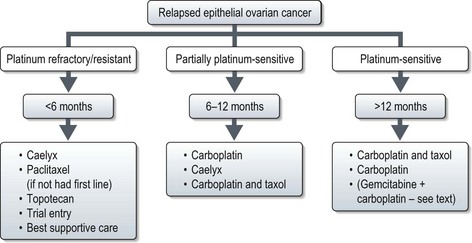

Relapse

Presentation of relapse

Relapse may be defined by conventional RECIST criteria (p. 44) or by the gynaecological cancer inter-group (GCIG) CA-125 criteria. CA-125 relapse for those who had elevated pre-treatment value which normalized after first line treatment (60% of all new patients) is defined as ≥2× upper limit of normal on two occasions not less than 1 week apart. Patients in whom CA-125 was elevated but never normalized (30% of all new patients): relapse is defined as a CA-125 value ≥2× nadir value on two occasions. The definition of relapse in patients with normal CA-125 prior to initial treatment (10% of all new patients) is similar to that of patients with elevated CA-125 which normalized after first line treatment.

Follow-up

Most (approximately 95%) recurrences will occur in the first 3 years and relapse after 5 years is rare. Follow-up is directed at detecting localized relapse which is potentially curable with surgery or radiotherapy, e.g. local vaginal vault relapse. Follow-up should include clinical examination, CA-125 (if elevated at presentation) and intermittent imaging if CA-125 was not informative or with symptoms. A typical follow-up would be 3-monthly for 2–3 years then 6-monthly up to 5 years. Patients with an informative CA-125 can become very focused on their blood result at each appointment so a clear plan of action with a raised CA-125 is recommended as there is no evidence that treatment with an asymptomatic elevated CA-125 improves outcome.

Endometrial cancer

Aetiology

Table 13.2 shows the risk factors for endometrial cancer. Less than 5% of endometrial cancers are hereditary, and most of these arise in women with hereditary non-polyposis coli (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome II (p. 51).

| Risk factor | Relative risk |

|---|---|

| Increased age | – |

| Unopposed oestrogen | 2–10 |

| Late menopause (after age 55) | 2 |

| Nulliparity | 2 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 3 |

| Obesity | 2–4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 |

| Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer | 22 to 50% lifetime risk |

| Tamoxifen | 2/1000 |

Pathogenesis and pathology

Histologic types of endometrial malignancies are as follows:

Diagnosis and staging

Initial investigations

Further investigations

Staging

The FIGO postoperative surgico-pathological staging system is given in Box 13.6.

Box 13.6

FIGO staging of endometrial cancer

Stage I* Tumour confined to the corpus uteri (includes endocervical gland involvement)

Stage II Tumour invades cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus

Prognostic factors

The most important prognostic factors are stage, age, depth of myometrial invasion >50%, grade 3, serous or clear cell histology and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). Table 13.3 shows the 5-year survival rate according to stage and grade.

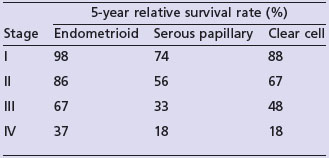

Endometrioid cancer presents more commonly with stage I and II (86%) than serous papillary (57%) or clear cell (70%). However, serous papillary and clear cell carcinomas have a poorer prognosis even after their stage at presentation is taken into account (see Table 13.4).

Treatment (Figure 13.5)

Stage I disease

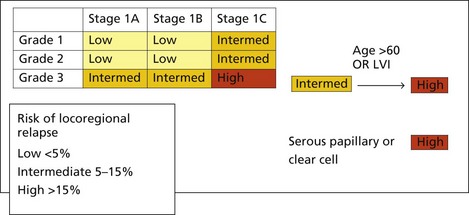

Adjuvant radiotherapy (Box 13.7)

Meta-analyses show that EBRT reduces locoregional recurrence in stage I endometrial cancer by 72% but does not have any benefit on survival. Three quarters of locoregional recurrences are restricted to the vagina, and most of these are curable with vaginal radiotherapy. However, it is important to define the risk of loco-regional recurrence to choose patients for adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy is to prevent uncontrolled pelvic disease and to prevent stress and morbidity associated with a diagnosis and treatment of a relapse. A general consensus is that radiotherapy is considered only if the risk of relapse is >15% (see Box 13.8). Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with intermediate risk remains controversial. In this group, PORTEC-1 identified a subgroup of patients (those aged more than 60 years with 1C or G3 disease) who have an 18% risk of locoregional relapse. The GOG 33 study identified lymphovascular invasion (LVI) as a significant poor prognostic factor for locoregional relapse (HR = 2.4, p = 0.005) Most centres in the UK include LVI as a high risk factor, and would offer patients adjuvant EBRT +/− brachytherapy to patients with 1C or G3 disease if they were either >60 or had LVI, sometimes described as high-intermediate risk. Early results of PORTEC-2 trial suggest that vaginal brachytherapy (BT) alone may be sufficient for this group of patients.

Stage II

For patients with cervical involvement (clinically or on MRI prior to surgery), a modified radical hysterectomy with bilateral lymph node dissection is indicated. This involves resection of a parametrial and paracervical tissue, and a cuff of 2 cm of upper vagina. Evidence show that radical hysterectomy results in an improved survival in stage II patients compared to standard hysterectomy (93% vs. 89% at 5 years). For patients with adequate tumour free margins and negative nodes there is no evidence that the addition of radiotherapy improved survival. Those with positive margins or involved nodes should receive adjuvant EBRT and BT.

Stage III–IV

Radiotherapy (Box 13.7)

Patients with optimal debulking should also be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy based on the results of GOG 122 (see below) followed by radiotherapy for those with a complete clinical response.

Chemotherapy for Stage III–IV (Box 13.9)

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Recurrent disease

For patients with a vault recurrence who have not previously received radiotherapy, radical radiotherapy is the treatment of choice (Box 13.8). Those patients who had previously received only BT can have EBRT with a boost if tumour is <0.5 cm. In the PORTEC-1 study 75% of patients with pelvic recurrence could be treated with curative intent and 85% achieved complete remission. The survival rate after relapse was 69% at 3 years in the control group compared with 13% in patients who had received EBRT up-front.

Patients not suitable for salvage surgery or radiotherapy may be treated with systemic therapy.

Special situations

Serous papillary and clear cell carcinoma

The principles of surgery for both these tumours parallel those for ovarian cancer (p. 198). Optimal therapy of early-stage papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas remains undefined. However the high relapse rates indicate that surgery alone is inadequate. Hence, all women with resected stage IB, IC, and II USPC or clear cell cancers may be offered platinum based chemotherapy (usually with carboplatin and taxol) with postoperative radiotherapy (EBRT+VBT, VBT or EBRT alone) in those with a complete clinical response. Most centres would also offer adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for stage IA serous papillary carcinoma in which there was any residual disease at hysterectomy following biopsy. Some centres consider whole abdominal radiation for UPSC because of the high rate of abdominal relapse, though the benefit has not been established.

Cervical cancer

Introduction and aetiology

There are a number of risk factors implicated in the development of cervical cancer such as sexual activity under the age of 20, smoking, immunosuppression, and infection with sexually transmitted diseases. Human papilloma virus (HPV) has emerged as the principal causative agent in the majority of cases of cervical cancer. The most frequent subtypes are 16 or 18.

Pathogenesis and pathology

Squamous cell and adenocarcinomas account for 90–95% of the cervical cancers. Other histologic types are shown in Box 13.10.

Evaluation and staging

Pretreatment evaluation

Staging

The FIGO staging is given in Table 13.5 which does not take into consideration the findings on imaging.

| Stage I confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus disregarded) |

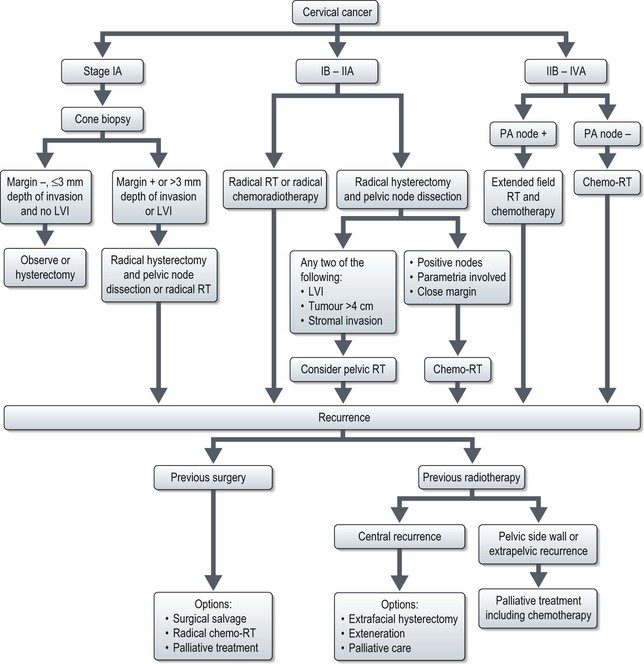

Management (Figure 13.7)

Stage IA disease

Stage IA1

IA1 without lymphovascular invasion (LVI) the treatment options are:

Stage IA2

Box 13.11

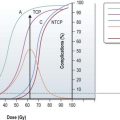

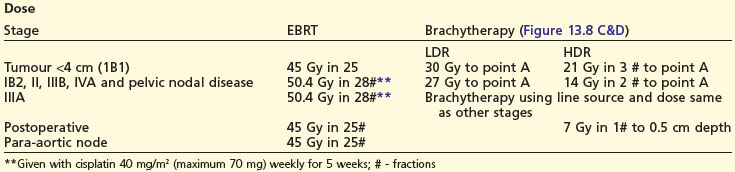

Radiotherapy in cervical cancer

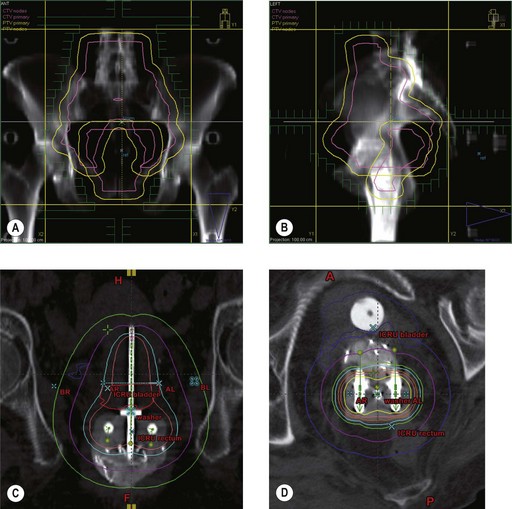

Target volume definition

Stage IB and IIA

Stage IB1 and IIA1 (<4 cm tumour)

Surgery involves removal of the uterus, upper third of vagina, bilateral parametria, uterosacral, utero-vesical ligaments and bilateral pelvic lymph nodes. Para-aortic lymph node sampling is indicated if there is clinical suspicion of nodal involvement to plan radiotherapy fields. Radiotherapy is with external beam pelvic irradiation combined with intracavitary applications, which deliver a dose of equivalent to 80–85 Gy to point A (Box 13.11).

Patients with more than two involved pelvic nodes are usually offered postoperative radiotherapy.

Stage IB2 and IIA2 (>4 cm tumour)

Stage IV

Stage IVA

The majority of stage IVA patients are of poor performance status or with many co-morbidities and extensive local disease, and are best treated with palliative treatment (radiotherapy or chemotherapy). Patients with poor general health, or extensive local disease can be offered best supportive care.

Recurrence

Recurrence after primary radiotherapy

Selected patients may be considered for pelvic exenteration, which is the only potentially curative treatment after primary irradiation. Those with resectable central recurrences that involve the bladder and/or rectum without evidence of intraperitoneal or extra pelvic spread and who have a dissectable tumour-free plane along the pelvic sidewall are potentially suitable. Surgery should be undertaken only in centres with appropriate facilities and expertise. The prognosis is better for patients with a disease-free interval greater than six months, a recurrence 3 cm or less in diameter, and no sidewall fixation. The 5-year survival for patients selected for treatment with pelvic exenteration is between 30–60% and the operative mortality should be <10%.

Ovarian germ cell tumours

Pathology

Investigations and staging

Initial investigations include estimation of serum tumour markers and imaging.

Tumour markers

Other markers include lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in dysgerminomas (88% have raised serum LDH isoenzyme-10) and placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) – raised in >95% of dysgerminomas. More than 50% of GCTs express CA-125 but its role in clinical management not known.

Imaging

Dysgerminomas and non-dysgerminomas exhibit different radiological features. On CT (Figure 13.9) and MRI dysgerminoma shows multiloculated solid mass divided by fibrovascular septa. There can be associated abdominal lymphadenopathy. Calcification is rare in dysgerminoma but when present it appears as a speckled pattern.

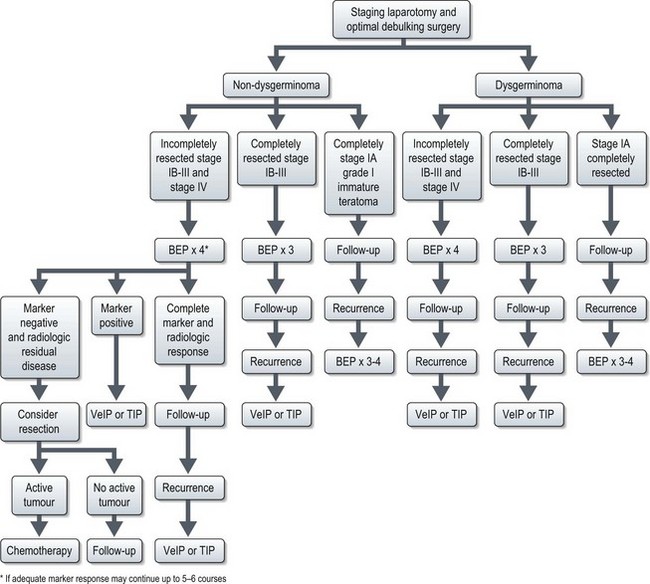

Management (Figure 13.10)

Germ cell tumours are potentially curable malignancies with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Postoperative management

Dysgerminoma

Adequately staged FIGO IA dysgerminoma has long-term survival of more than 90%, and these patients are observed without any postoperative treatment. The recurrences (rate of 15–25%) in these patients can be effectively salvaged with chemotherapy. All other patients need adjuvant treatment after maximal debulking with or without fertility preservation.

Completely resected stage IB–III and those without staging laparotomy are treated with three courses of standard chemotherapy with BEP regime (Box 13.12). Disease-free survival of completely resected dysgerminoma is very high, approaching 100% and that of advanced disease is in the range of 60–80%. Incompletely resected stage II–IV are treated with 3–4 courses of BEP.

Non-dysgerminoma

The optimal number of courses of chemotherapy for GCT is unclear, unlike testicular tumours. One GOG study had shown that three courses of BEP will nearly always prevent recurrence in well-staged patients with completely resected ovarian germ cell tumours. However, those with a raised tumour marker but with no measurable disease should receive two more courses of chemotherapy after normalization of serum markers and those with bulky residual tumour may need 5–6 courses.

The role of carboplatin in place of cisplatin is undergoing clinical trials.

Recurrence

There is no clear standard for treatment of relapsed ovarian germ cell tumour. Based on experience of testicular tumours, ovarian GCTs can also be divided into those which are platinum resistant and those which are platinum sensitive. Platinum resistant tumours are defined as progressive disease during treatment or during 6–8 weeks of stopping treatment. Prognosis in these cases is dismal and high dose chemotherapy or experimental drugs are advocated. Platinum sensitive tumours are defined as relapses occurring after 6–8 weeks of discontinuation of treatment. Prognosis in these cases is good. They are treated with platinum containing salvage chemotherapy regimens such as VeIP or TIP (Box 13.12).

Sex cord stromal tumours

Granulosa cell tumour

These tumours usually present with large masses with features of increased oestrogen production. These can be associated with endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. TAH-BSO is the treatment of choice in those who have completed their family. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is an option for young women with stage I disease. Role of adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery is unknown. The approaches vary from routine chemotherapy for stage II–IV to no treatment until recurrence. Retrospective data suggests that adults with stage III–IV disease have a better progression free survival with adjuvant chemotherapy. The most commonly used chemotherapy is BEP (p. 223). Alternative options include combinations of carboplatin with paclitaxel and cisplatin with etoposide.

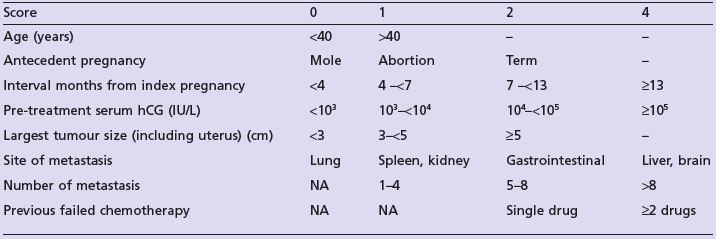

Gestational trophoblastic disease

Clinical features

All women are followed up with serum beta-hCG estimation after evacuation of a molar pregnancy to identify persistent disease. 5–10% women may need chemotherapy for persistent GTD. The indications for chemotherapy are shown in Box 13.13.

Assessment prior to chemotherapy

Treatment

Low-risk disease (score ≤6)

Single agent chemotherapy is the treatment of choice and the commonly used agents are methotrexate and dactinomycin (Box 13.15). Methotrexate does not cause alopecia. Around 10–20% patients do not respond to methotrexate, and salvage treatment options are single agent D-actinomycin (if hCG level is low) or combination chemotherapy (if hCG level is high) (Box 13.15). Selected patients are salvaged with hysterectomy.

Box 13.15

Chemotherapy in GTD

Vulval cancer

Diagnosis and staging

The size and location of the lesion should be documented, and any involvement of adjacent structures such as vagina, urethra, base of bladder or anus, should be noted. The diagnosis of vulval cancer is made after biopsy. Vulval cancer is staged using the FIGO classification (Box 13.16).

Box 13.16

FIGO staging of vulval cancer

lower urethra,

lower urethra,  lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes.

lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes. lower urethra,

lower urethra,  lower vagina, anus) with positive inguino-femoral lymph nodes.

lower vagina, anus) with positive inguino-femoral lymph nodes.

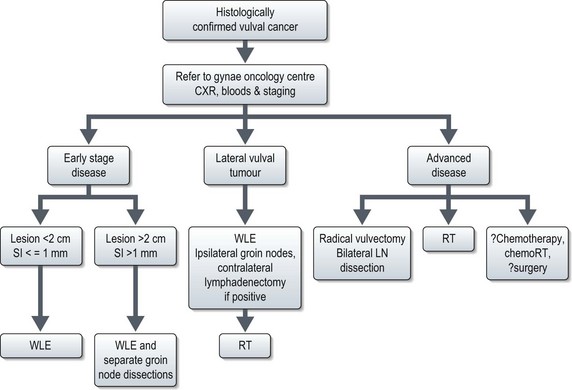

Management (Figure 13.11)

Advanced disease

Primary radiotherapy is the treatment of choice in those women with larger, more advanced lesions involving bladder or rectum, or who are considered unsuitable for surgery. Nodal disease may be dissected prior to management of primary tumour. Initial treatment involves 50 Gy at 1.7–1.8 Gy per fraction to include pelvis, inguinal nodes and primary tumour. The second phase of treatment is to the gross disease to deliver a total dose of 60–70 Gy. The exact role of the combination of chemotherapy (cisplatin alone or in combination with 5-FU) with radiotherapy is not fully explored.

Cancer of the vagina

Pathology

The common histologic types are:

Presentation

Diagnosis and staging

The diagnosis of primary vaginal cancer is made by histology and clinical examination. Tumours extending to the external cervical os are classified as cervical cancers, while tumours involving the vulva as vulval cancers. MRI scan is useful in assessing local extension of tumour. FIGO staging for vagina is given in Box 13.17.

Box 13.17

FIGO staging of vaginal cancer

| Stage I | Tumour limited to vaginal wall |

| Stage II | Tumour involving the subvaginal tissue but not extending to pelvic side wall |

| Stage III | Tumour extending up to pelvic side wall |

| Stage IVa | Spread to adjacent organs and/or direct extension beyond true pelvis |

| Stage IVb | Distant |

Principles of management

Surgery

In stage II disease with lesions in sites that would allow a less aggressive procedure than a radical vaginectomy and with minimal extension outside the vaginal wall, surgery may be considered.

In young patients requiring radiotherapy, laparotomy is done to transpose ovaries.

Colombo N, Peiretti M, Castiglione M. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):24-26.

Han LY, Kipps E, Kaye SB. Current treatment and clinical trials in ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:521-534.

Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491-505.

Gehrig PA, Bae-Jump VL. Promising novel therapies for the treatment of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:187-194.

Goonatillake S, Khong R, Hoskin P. Chemoradiation in gynaecological cancer. Clin Oncol. 2009;21:566-572.

Taylor A, Powell ME. Conformal and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Clin Oncol. 2008;20:417-425.

del Campo JM, Prat A, Gil-Moreno A, et al. Update on novel therapeutic agents for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:S72-S76.

Koulouris CR, Penson RT. Ovarian stromal and germ cell tumors. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:126-136.

Crosbie EJ, Slade RJ, Ahmed AS. The management of vulval cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:533-539.

Gray HJ. Advances in vulvar and vaginal cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2010 May 13. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 20471671

invasion of the myometrium, the risk is approximately 25%. With both these factors, there is a 34% risk of pelvic node involvement, and a 24% risk of aortic node involvement. North American practice is to perform routine bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) with or without para-aortic lymphadenectomy but there is no clear evidence that lymphadenectomy improves survival. The initial results of the ASTEC trial comparing pelvic lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in mostly stage I disease showed similar survival and progression free survival with both approach and hence the UK practice is to perform lymph node sampling of clinically suspicious nodes only. The rationale being patients with micrometastases will be identifiable as having a high risk of locoregional relapse and these patients can be stratified to receive radiotherapy. Some UK centres perform lymphadenectomy in stage I patients with a high risk of locoregional relapse, and omitting External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to those with uninvolved nodes.

invasion of the myometrium, the risk is approximately 25%. With both these factors, there is a 34% risk of pelvic node involvement, and a 24% risk of aortic node involvement. North American practice is to perform routine bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) with or without para-aortic lymphadenectomy but there is no clear evidence that lymphadenectomy improves survival. The initial results of the ASTEC trial comparing pelvic lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in mostly stage I disease showed similar survival and progression free survival with both approach and hence the UK practice is to perform lymph node sampling of clinically suspicious nodes only. The rationale being patients with micrometastases will be identifiable as having a high risk of locoregional relapse and these patients can be stratified to receive radiotherapy. Some UK centres perform lymphadenectomy in stage I patients with a high risk of locoregional relapse, and omitting External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to those with uninvolved nodes.

upper urethra,

upper urethra,  upper vagina), or distant structures.

upper vagina), or distant structures.