Chapter 13 CANCER OF THE PANCREAS AND PANCREATIC CYSTIC LESIONS

PANCREATIC CANCER

Clinical features

Clinical signs include evidence of weight loss, jaundice, hepatomegaly, a palpable gall bladder, Troisier’s sign (enlarged left supraclavicular lymph nodes), an abdominal mass and ascites. In patients suspected of having a pancreatic malignancy, weight loss, hyperbilirubinaemia and an increased CA 19-9 may be highly predictive of pancreatic malignancy. Surgical exploration should be considered in these patients even in the absence of a preoperative diagnosis.

Diagnostic methods

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Results in the same efficacy as CE-CT and is used if patients cannot tolerate intravenous contrast.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy allows for direct observation of the pancreas and for biopsies and cytological washings to be taken. This is particularly important in cases where the other modalities are equivocal. It may also preclude unnecessary laparotomies. Laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS) is useful for liver and pancreas scanning.

Treatment

Surgery

Contraindications to surgery include metastases in the liver, peritoneum, omentum, and extra-abdominal sites (see Table 13.1 for the TNM classification of tumours).

| Tumour | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumour limited to the pancreas, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumour extends directly into any of the following: duodenum, bile duct peripancreatic tissues |

| T4 | Tumour extends directly into any of the following: stomach, spleen, colon, adjacent large vessels |

| Lymph node metastases | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastases |

| Distant metastases | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Octreotide (a somatostatin analogue) has been shown to reduce postoperative morbidity.

Complications of surgery include fistulae, delayed gastric emptying, bleeding and intra-abdominal abscess. Despite advances in surgical procedures, 5-year survival rates range from 10% to 25%. Unfortunately, approximately 88% of cancers are unresectable at diagnosis because of metastases. Good predictors of survival are small tumours (diameter less than 2 cm), negative lymph nodes, well differentiated histology and surgery in a high volume specialised centre. The difficulty in diagnosis is compounded by the fact that it may be difficult to differentiate benign chronic pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. In a recent series 5%–15% of patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy for suspected cancer of the head of pancreas or periampullary region were found to have benign disease.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Chemotherapy is the primary therapeutic modality for patients with metastatic disease, the objectives of which are palliation of symptoms, improvement in the quality of life and to extend survival. Gemcitabine is used for its clinical-benefit response. Compared with fluorouracil, there is improvement in disease-related signs and symptoms. It demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in clinical benefit response as measured by weight gain, decreased pain medication need or increased performance status and a 5 week gain in median survival over that achieved with fluorouracil. An advance in therapy has been the use of a new agent, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib, combined with gemcitabine. Radiotherapy has not shown to be of any benefit compared to chemotherapy alone. As yet, there is no clear evidence that combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy is of significant benefit.

PANCREATIC CYSTIC LESIONS

Differential diagnosis

Once a cystic lesion is observed, a pseudocyst should be excluded. This usually presents in a setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis. In addition, pseudocysts do not have an epithelial lining and are collections of pancreatic secretions that have arisen from a duct that has been disrupted from inflammation or obstruction. Imaging should confirm the diagnosis.

SUMMARY

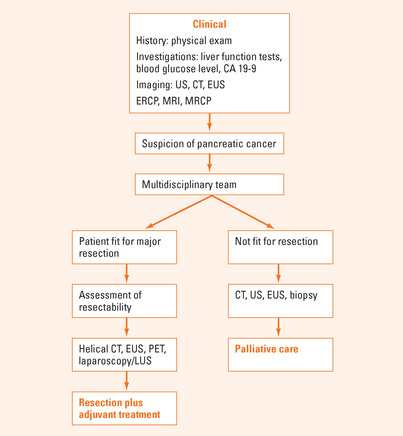

Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive cancer with a low survival time. The major risk factors are increasing age, smoking, hereditary pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and dietary factors. The classical presentation is painless obstructive jaundice, weight loss and back pain (Figure 13.1). Laboratory investigations include a full blood count, liver function tests and CA 19-9. Imaging procedures appropriate for diagnosis and staging include CE-CT Scan, EUS (with fine needle aspiration), MRI, MRCP, ERCP and PET scan.

Early surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic cancer, but there is only a 10%–15% chance of survival at 5 years. The most common operation is a Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy. Chemotherapy is the primary therapeutic modality for patients with metastatic disease. Gemcitabine is the drug of choice. An advance in therapy is the agent erlotinib combined with gemcitabine.

Canto MI, Goggins M, Hruban RH, et al. Screening for early pancreatic neoplasia in high risk individuals: a prospective controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:766-781.

Canto MI, Kennedy T, Preczewski L, et al. Screening for pancreatic neoplasia in high risk individuals: who, what, when, how. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S46-S48.

Chak A. Pancreatic cysts: much ado or not enough? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:964-966.

Eloubeidi MA, Desmond RA, Wilcox CM, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in pancreatic cancer: a population based study. Am J Surg. 2006;192:322-329.

Kennedy T, Preczewski L, Stocker SJ, et al. Incidence of benign inflammatory disease in patients undergoing Whipple procedure for clinically suspected carcinoma: a single-institution experience. Am J Surg. 2006;191:437-441.

Khalid A, McGrath KM, Zahid M, et al. The role of pancreatic cyst fluid molecular analysis in predicting cyst pathology. Clin Gastroentrol Hepatol. 2005;3:967-973.

Levy MJ. Screening for pancreatic cancer: searching for the right needle in the haystack. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:684-687.